By Using This Material, You Are Consenting to Abide by This Copyright Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1St Century B.C. to 6Th Century A.D.)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. ISSN 2250-3226 Volume 7, Number 2 (2017), pp. 149-152 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1st Century B.C. to 6th Century A.D.) Vaishali Bhagwatkar Barkatullah Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal (M.P.) India Abstract Buddhism is a world religion, which arose in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama who was deemed a "Buddha" ("Awakened One"). Buddhism spread outside of Magadha starting in the Buddha's lifetime. With the reign of the Buddhist Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist community split into two branches: the Mahasaṃghika and the Sthaviravada, each of which spread throughout India and split into numerous sub-sects. In modern times, two major branches of Buddhism exist: the Theravada in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and the Mahayana throughout the Himalayas and East Asia. INTRODUCTION Buddhism remains the primary or a major religion in the Himalayan areas such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, the Darjeeling hills in West Bengal, and the Lahaul and Spiti areas of upper Himachal Pradesh. Remains have also been found in Andhra Pradesh, the origin of Mahayana Buddhism. Buddhism has been reemerging in India since the past century, due to its adoption by many Indian intellectuals, the migration of Buddhist Tibetan exiles, and the mass conversion of hundreds of thousands of Hindu Dalits. According to the 2001 census, Buddhists make up 0.8% of India's population, or 7.95 million individuals. Buddha was born in Lumbini, in Nepal, to a Kapilvastu King of the Shakya Kingdom named Suddhodana. -

Who Are the Buddhist Deities?

Who are the Buddhist Deities? Bodhisatta, receiving Milk Porridge from Sujata Introduction: Some Buddhist Vipassana practitioners in their discussion frown upon others who worship Buddhist Deities 1 or practice Samadha (concentrationmeditation), arguing that Deities could not help an individual to gain liberation. It is well known facts, that some Buddhists have been worshipping Deities, since the time of king Anawratha, for a better mundane life and at the same time practicing Samadha and Vipassana Bhavana. Worshipping Deities will gain mundane benefits thus enable them to do Dana, Sila and Bhavana. Every New Year Burmese Buddhists welcome the Sakka’s (The Hindu Indra God) visit from the abode of thirty three Gods - heaven to celebrate their new year. In the beginning, just prior to Gotama Buddha attains the enlightenment, many across the land practice animism – worship spirits. The story of Sujata depicts that practice. Let me present the story of Sujata as written in Pali canon : - In the village of Senani, the girl, Sujata made her wish to the tree spirit that should she have a good marriage and a first born son, she vowed to make yearly offering to the tree spirits in grateful gratitude. Her wish having been fulfilled, she used to make an offering every year at the banyan tree. On the day of her offering to the tree spirit, coincidentally, Buddha appeared at the same Banyan tree. On the full moon day of the month Vesakha, the Future Buddha was sitting under the banyan tree. Sujata caught sight of the Future Buddha and, assuming him to be the tree-spirit, offered him milk-porridge in a golden bowl. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Researchnstitute, Poona, pp.171-201 Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha to the time of Asoka which is as follows:-- 1. The simple statements of Buddhist doctrine now found, in identical words, in paragraphs or verses recurring in all the books. 2. Episodes found, in identical words, in two or more of the existing books. 3. The Silas, the Parayana, the Octades, the Patimokkha. 4. The Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, and Samyutta Nikayas. 5. The Sutta-Nipata, the Thera-and Theri-Gathas, the Udanas, and the Khuddaka Patha. 6. The Sutta Vibhanga, and Khandhkas. 7. The Jatakas and the Dhammapadas. 8. The Niddesa, the Itivuttakas and the Patisambbhida. 9. The Peta and Vimana-Vatthus, the Apadana, the Cariya-Pitaka, and the Buddha-Vamsa. 10. The Abhidhamma books; the last of which is the Katha-Vatthu, and the earliest probably the Puggala-Pannatti. This chronological table of early Buddhist; literature is too catechetical, too cut and dried, and too general to be accepted in spite of its suggestiveness as a sure guide to determination of the chronology of the Pali canonical texts. The Octades and the Patimokkha are mentioned by Rhys Davids as literary compilations representing the third stage in the order of chronology. The Pali title corresponding to his Octades is Atthakavagga, the Book of Eights. The Book of Eights, as we have it in the Mahaniddesa or in the fourth book of the Suttanipata, is composed of sixteen poetical discourses, only four of which, namely, (1.) Guhatthaka, (2) Dutthatthaka. -

Buddhism in Myanmar a Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1

Buddhism in Myanmar A Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1. Earliest Contacts with Buddhism 2. Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu Kingdoms 3. Theravada Buddhism Comes to Pagan 4. Pagan: Flowering and Decline 5. Shan Rule 6. The Myanmar Build an Empire 7. The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Notes Bibliography Preface Myanmar, or Burma as the nation has been known throughout history, is one of the major countries following Theravada Buddhism. In recent years Myanmar has attained special eminence as the host for the Sixth Buddhist Council, held in Yangon (Rangoon) between 1954 and 1956, and as the source from which two of the major systems of Vipassana meditation have emanated out into the greater world: the tradition springing from the Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw of Thathana Yeiktha and that springing from Sayagyi U Ba Khin of the International Meditation Centre. This booklet is intended to offer a short history of Buddhism in Myanmar from its origins through the country's loss of independence to Great Britain in the late nineteenth century. I have not dealt with more recent history as this has already been well documented. To write an account of the development of a religion in any country is a delicate and demanding undertaking and one will never be quite satisfied with the result. This booklet does not pretend to be an academic work shedding new light on the subject. It is designed, rather, to provide the interested non-academic reader with a brief overview of the subject. The booklet has been written for the Buddhist Publication Society to complete its series of Wheel titles on the history of the Sasana in the main Theravada Buddhist countries. -

Th E Phaungtaw-U Festival

NOTES TH_E PHAUNGTAW-U FESTIVAL by SAO SAIMONG* Of the numerous Buddhist festivals in Burma, the Phaungtaw-u Pwe (or 'Phaungtaw-u Festival') is among the most famous. I would like to say a few words on its origins and how the Buddhist religion, or 'Buddha Sii.sanii.', came to Burma, particularly this part of Burma, the Shan States. To Burma and Thailand the term 'Buddha Sii.sanii.' can only mean the Theravii.da Sii.sanii. or simply the 'Sii.sanii.'. I Since Independence this part of Burma has been called 'Shan State'. During the time of the Burmese monarchy it was known as Shanpyi ('Shan Country', pronounced 'Shanpye'). When th~ British came the whole unit was called Shan States because Shanpyi was made up of states of various sizes, from more than 10,000 square miles to a dozen square miles. As I am dealing mostly with the past in this short talk I shall be using this term Shan States. History books of Burma written in English and accessible to the outside world tell us that the Sii.sanii. in its purest form was brought to Pagan as the result of the conversion by the Mahii.thera Arahan of King Aniruddha ('Anawrahtii.' in Burmese) who then proceeded to conquer Thaton (Suddhammapura) in AD 1057 and brought in more monks and the Tipitaka, enabling the Sii.sanii. to be spread to the rest of the country. We are not told how Thaton itself obtained the Sii.sanii.. The Mahavamsa and chronicles in Burma and Thailand, however, tell us that the Sii.sanii. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................ -

Strong Roots Liberation Teachings of Mindfulness in North America

Strong Roots Liberation Teachings of Mindfulness in North America JAKE H. DAVIS DHAMMA DANA Publications at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies Barre, Massachusetts © 2004 by Jake H. Davis This book may be copied or reprinted in whole or in part for free distribution without permission from the publisher. Otherwise, all rights reserved. Sabbadānaṃ dhammadānaṃ jināti : The gift of Dhamma surpasses all gifts.1 Come and See! 1 Dhp.354, my trans. Table of Contents TO MY SOURCES............................................................................................................. II FOREWORD........................................................................................................................... V INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 1 Part One DEEP TRANSMISSION, AND OF WHAT?................................................................ 15 Defining the Topic_____________________________________17 the process of transmission across human contexts Traditions Dependently Co-Arising 22 Teaching in Context 26 Common Humanity 31 Interpreting History_____________________________________37 since the Buddha Passing Baskets Along 41 A ‘Cumulative Tradition’ 48 A ‘Skillful Approach’ 62 Trans-lation__________________________________________69 the process of interpretation and its authentic completion Imbalance 73 Reciprocity 80 To the Source 96 Part Two FROM BURMA TO BARRE........................................................................................ -

A History of Southeast Asia

ARTHUR AHISTORYOF COTTERELL SOUTHEAST AHISTORYOF ASIA SOUTHE A HISTORY OF OF HISTORY About the Author A History of Southeast Asia is a sweeping and wide-ranging SOUTHEAST Arthur Cotterell was formerly principal of Kingston narration of the history of Southeast Asia told through historical College, London. He has lived and travelled widely anecdotes and events. in Asia and Southeast Asia, and has devoted ASIA much of his life to writing on the region. In 1980, Superbly supported by over 200 illustrations, photographs and he published !e First Emperor of China, whose maps, this authoritative yet engagingly written volume tells the account of Qin Shi Huangdi’s remarkable reign was history of the region from earliest recorded times until today, translated into seven languages. Among his recent covering present-day Myanmar, !ailand, Cambodia, Laos, AS books are Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, the Philippines, Indonesia Swift Fall 1415–1999, and Asia: A Concise History, and East Timor. T A published in 2011, the "rst ever coverage of the entire continent. “Arthur Cotterell writes in a most entertaining way by putting a human face on the history of Asia. Far too often, “Arthur Cotterell writes in a most entertaining history books are dry and boring and it is refreshing SIA way by putting a human face on the history of Asia.” to come across one which is so full of life. - to be changed” – Peter Church, OAM, author of A Short History of South East Asia, on Arthur Cotterell – Professor Bruce Lockhart -

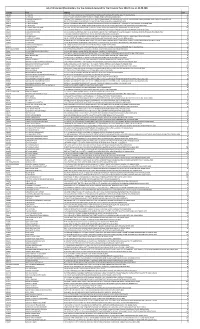

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A04314 A B FONTES 104 IVTH CROSS KALASIPALYAM NEW EXTENSION BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560002,INDIA 25 A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,PIN-600004,INDIA 180 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,PIN-623501,INDIA 90 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,PIN-682002,INDIA 25 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,PIN-221001,INDIA 25 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560085,INDIA 25 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560078,INDIA 360 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-532001,INDIA 18 A03555 A LAKSHMINARAYANA C/O G ARUNACHALAM RANA PLOT NO 30 LEPAKSHI COLONY WEST MARREDPALLY SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-500026,INDIA 25 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,PIN-302006,INDIA 25 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,PIN-632007,INDIA 23 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J -

A Historical and Comparative Analysis of Renunciation and Celibacy in Indian Buddhist Monasticisms

Going Against the Grain: A Historical and Comparative Analysis of Renunciation and Celibacy in Indian Buddhist Monasticisms Phramaha Sakda Hemthep Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Cardiff School of History, Archeology and Religion Cardiff University August 2014 i Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MPhil. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 2 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A Bibliography is appended. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 3 I confirm that the electronic copy is identical to the bound copy of the dissertation Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 4 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… STATEMENT 5 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access approved by the Graduate Development Committee. Signed …………………………… (Phramaha Sakda Hemthep) Date ………31/08/2014….…… ii Acknowledgements Given the length of time it has taken me to complete this dissertation, I would like to take this opportunity to record my sense of deepest gratitude to numerous individuals and organizations who supported my study, not all of whom are mentioned here.