Co-Building of Socio-Technical and Organisational Innovations in Fish Farming Systems In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Département Bamoun 42 P

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REfIlUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIENTIFIQUE ET 'rECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE OR5TOM DE YAOUNDE 1 DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES . DU DEPARTEMENT BAMOUN ~prèS la documentation réunie ~ ~ction de Géographiy de l'ORS~ REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE n° 16 SH. n° 44 YAOUNDE Janvier 1968 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fesc. Tabl.eau de là population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. N° 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des ~illages de la Haute-Sanaga, 53 p. Août 1965 SH. N° 23 Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, ~~ p. Octobre 1965 SH. N° ?4 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du l'-Jtem 126 p. Décembre 1965 SH. N° 26 Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N" 27 Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 5H. N° 28 Fasc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la Lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. N° 29 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam 60 P. Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko 34 p. Juin 1966 SH 39 Fasc. 13 Dictionnaire des villages de Lom-et-Djérem 35 p. Juillet 1967 SH. 40 Fasc. 14 Dictionnaire des villages de la Kadei 52 p. Août 1967 SH. 41 Fasc. -

World Bank Document

Archives Charge Out- 4/26/2017 'The.-, .. ,~ I, ~ k.-, ~ Return to Archives When Complete /5\,nr;;(, h ..re~.i ,.. w,~ ••• II I Item Requested: 229311 ~ ~.~ II II II II 1111111111 1111 11 Archaves 229311 Item Location \\I II II II I II\ 1\1 II\ \\ I\ I 11 87274F Other# 1381605 PrQJe;t Completion Report - July 16. 1980 R1981-015 46-14 10:Si5B N-249-3-01 Requestor MUNOZ, J::.:sE-MARIA 1 "'v\1 ednec,day Apnl 26. 20H at 10 11 30 AM ( 1111111111 ll 11111111111111 II ::,:: u u, C/l rl E--l u, u rl w ', c:: E--l 0 (ij p:; p:; 0 0 p_, ,-::i p_, w ;:,.. "Q p:; c:: 0 ~ (ij z co z ::c 0 0\ 0 0 ::,:: H rl 0 H u E--l p:; iil N ~ 0\ ,-::i N '°,-j ! § -:::t ~ u H 0 t>, ::c: w u rl E--l •ri ;:l 'O E--l ', p QJ u H µ:i ~ u ', -....... 0 ::,:: p:; f@ u p_, 0 u Lf') µ:i 01 C/l 0\ c:: (ij c:: 31 0 c:: ·ri 0 (){) ·rl (I) rn p:; ·ri > (ij ·rl cJ p ·rl H rn 4-l t>, (ij ~ ::;: .w .c rn oO (I) ,,-f :s: tr: Public Disclosure Authorized Disclosure Public Authorized Disclosure Public Authorized Disclosure Public Authorized Disclosure Public CAMEROON SECOND AND THIRD HIGHWAY PROJECTS Loan 935 CM/Credit 429 CM and Loan 1515 CM PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NUMBER BAS IC DATA SHEET ..••••••..•••..•.•••..••.•••••••••...•• I 11' INTRODUCTION e • 0 • ,0 & .., & 10 & • 0 0 • & 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 • 0 •• 0 & & • & " • & 0 • 0 e • 10 0 & 1 II. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Dekadal Climate Alerts and Probable Impacts for the Period 11Th to 20Th March, 2020

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ----------- ----------- OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR NATIONAL OBSERVATORY LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES ON CLIMATE CHANGE ----------------- ----------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECTORATE GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- ONACC www.onacc.cm; [email protected] ; Tel : (+237) 693 370 504 / 654 392 529 BULLETIN N° 38 Dekadal climate alerts and probable impacts for the period 11th to 20th March, 2020 March 2020 © ONACC March 2020, all rights reserved Supervision Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (ONACC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Ing. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (ONACC). Production Team (ONACC) Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (ONACC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Ing. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (ONACC). BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, PhD student and Technical staff, ONACC. ZOUH TEM Isabella, MSc in GIS-Environment. NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. MEYONG René Ramsès, M.Sc. in Physical Geography (Climatology/Biogeography). ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, ONACC ELONG Julien Aymar, M.Sc. Business and Environmental law. I. INTRODUCTION These forecasts are developed using spatial data -

Bamileke Bamileke Language & Culture in the Unitedstates

STUDYING BAMILEKE BAMILEKE LANGUAGE & CULTURE IN THE UNITEDSTATES Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Graffi Please contact the National African Language languages, whose attachment to the Bantu division is still Resource Center, or check the NALRC disputed. While some consider it as a Bantu or a semi-Bantu website at http://www.nalrc.indiana.edu/ language, others prefer to in-clude Bamileke in the Niger-Congo group. Bamileke is not an unique language. It seems that Bamileke Medumba stems from ancient Egyptian and is a root language for many other Bamileke variants. The Bamiléké languages, which are tonal, belong to the Grasslands Bantu Group of the Broad Bantu languages. Nearly every Bamileke kindom names its own dialect as a separate language. Bamiléké languages are not al-ways mutually intelligible between bordering kingdoms. The Bamileke are renowned for their skilled craftsmenship. Bamileke are particularly celebrated carvers in wood, ivory, and horn. Chief’s compounds are notable for their intricately carved door frames and columns. Much of the art produced by the Bamileke tribes are associated with NATIONAL AFRICAN royal ceremonies. Beadwork and masks are common in this LANGUAGE RESOURCE tribe. Even the king may put on a mask for an appearance at a CENTER (NALRC) Kuosi celebration which is a public dance held every other year as a display of the kingdom’s wealth. Bamileke of 701 Eigenmann Hall, 1900 E. 10th St. Bloomington, IN 47406 USA Cameroon raise their dead to the rank of ancestors, worthy BAMILEKE TRADITIONAL ATTIRE T: (812) 856 4199 | F: (812) 856 4189 of worship and sacrifice. -

1. General Overview

Report Multi-Sector Rapid Assessment in the West and Littoral Regions Format Cameroon, 25-29 September 2018 1. GENERAL OVERVIEW a) Background What? The humanitarian crisis affecting the North-West and the South-West Regions has a growing impact in the bordering regions of West and Littoral. Since April 2018, there has been a proliferation of non-state armed groups (NSAG) and intensification of confrontations between NSAG and the state armed forces. As of 1st October, an estimated 350,000 people are displaced 246,000 in the South-West and 104,000 in the North-West; with a potential increment due to escalation in hostilities. Why? An increasing number of families are leaving these regions to take refuge in Littoral and the West Regions following disruption of livelihoods and agricultural activities. Children are particularly affected due to destruction or closure of schools and the “No School” policy ordered by NSAG since 2016. The situation has considerably evolved in the past three months because of: i) the anticipated security flashpoints (the start of the school year, the “October 1st anniversary” and the elections); ii) the increasing restriction of movement (curfew extended in the North-West, “No Movement Policy” issued by non-state actors; and iii) increase in both official and informal checkpoints. Consequently, there has been a major increase in the number of people leaving the two regions to seek safety and/or to access economic and educational opportunities. Preliminary findings indicate that IDPs are facing similar difficulties and humanitarian needs than the one reported in the North-West and the South-West regions following the multisectoral needs assessment done in March 2018. -

1.3.6.NIC Cameroon, Richard Njouom, Cameroon

Pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009 in Cameroon: Epidemiological, Genetic and Antigenic characterization Richard Njouom1, Cyrille F. Djoko2, Lucy Ndip3 and Jean-Marc Reynes1 for the Cameroon Network of Laboratories for human influenza surveillance. 1. National Influenza Centre, Centre Pasteur du Cameroun , Yaounde, Cameroon 2. Global Viral Forecasting , Yaounde, Cameroon 3. Laboratory for Emerging Infectious Disease, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon Outline of the presentation 1. Geographic situation of Cameroon 2. Cameroon Network of influenza surveillance 3. Virological surveillance of influenza in Cameroon from November 1007 to November 2010 4. Characterization of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 in Cameroon 5. Conclusions/Challenges/Way forward WHO Global NIC Meeting, Hammamet, Tunisia Page 1 of 7 30 November 2010 - 3 December 2010 Geographic situation of Cameroon The World Africa 20 millions inhab. Age structure 10 regions 475,000 km2 0-14 years (42%) Raining season (June to Oct.) 15-64 years (55%) Dry season (Nov. to May) 65 years and over (3%) Cameroon Cameroon Network of influenza surveillance 45 sentinel sites located in 8 different regions. Extension in January 2010/UB North West Region Bamenda Extension in January 2009 1 Health Centre North Region Garoua South West Region 2 Health Centres Mutengene, Kumba, Manfe 3 Health Centres Yaounde : November 2007 Centre Region West Region Yaounde Bafoussam, Bandjoun, Foumban 5 Health Centres 3 Health Centres 8 Health Centres Littoral Region South Region East Region Douala HEVECAM, -

Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon During the First World War

Soldiers of their Own: Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon during the First World War by George Ndakwena Njung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolph (Butch) Ware III, Chair Professor Joshua Cole Associate Professor Michelle R. Moyd, Indiana University Professor Martin Murray © George Ndakwena Njung 2016 Dedication My mom, Fientih Kuoh, who never went to school; My wife, Esther; My kids, Kelsy, Michelle and George Jr. ii Acknowledgments When in the fall of 2011 I started the doctoral program in history at Michigan, I had a personal commitment and determination to finish in five years. I wanted to accomplish in reality a dream that began since 1995 when I first set foot in a university classroom for my undergraduate studies. I have met and interacted with many people along this journey, and without the support and collaboration of these individuals, my dream would be in abeyance. Of course, I can write ten pages here and still not be able to acknowledge all those individuals who are an integral part of my success story. But, the disservice of trying to acknowledge everybody and end up omitting some names is greater than the one of electing to acknowledge only a few by name. Those whose names are omitted must forgive my short memory and parsimony with words and names. To begin with, Professors Emmanuel Konde, Nicodemus Awasom, Drs Canute Ngwa, Mbu Ettangondop (deceased), wrote me outstanding references for my Ph.D. -

Prevalence of Soil Transmitted Helminths and Associated Risk Factors Among Children Residents in Bandjoun, West Region of Cameroon

ACTA SCIENTIFIC MICROBIOLOGY (ISSN: 2581-3226) Volume 3 Issue 10 October 2020 Research Article Prevalence of Soil Transmitted Helminths and Associated Risk Factors among Children Residents in Bandjoun, West Region of Cameroon Dzune Fossouo Dirane Cleopas1,2* and Yondo Jeannette3,4 Received: August 19, 2020 1Center for Research on Filariasis and others Tropical Diseases, Cameroon Published: October 07, 2020 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaounde 1, Cameroon © All rights are reserved by Dzune Fossouo 3Department of Biology Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutic Sciences, Dirane Cleopas and Yondo Jeannette. University of Dschang, Cameroon 4Department of Animal Biology, University of Dschang, Cameroon *Corresponding Author: Dzune Fossouo Dirane Cleopas, Center for Research on Filariasis and others Tropical Diseases, Cameroon. Abstract Geohelminth infections, such as Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and Hookworms are major public health concerns. These helminths distributed throughout the world with high prevalence in poor and socio-economically deprived communities in the tropics and subtropics cause morbidity and sometimes death. Our study aimed at evaluating the prevalence and intensity of infection of geohelminths and the risk factor in Bandjoun, West Region of Cameroon. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were carried out on three hundred and fifteen (315) stool samples collected from residents using the simple centrifugal flotation and McMaster count Ascaris lumbricoides technique respectively. Out of the 315 samples examined, twenty-one (6.7%) were infected with the eggs of at least one helminth Trichuris trichiura A. lumbricoides and parasite with prevalence and intensities of infection of 6.7% and 6971.4286 ±14662.4228 for and 0.3% and 50 T. -

Adapting the Sudden Landslide Identification

Adapting the Sudden Landslide Identication Product (SLIP) and Detecting Real-Time Increased Precipitation (DRIP) algorithms to map rainfall- triggered landslides in the West-Cameroon highlands (Central-Africa) ALFRED HOMERE NGANDAM MFONDOUM ( [email protected] ) Universite de Yaounde I https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5917-1275 Pauline Wokwenmendam Nguet Institute of Mining and Geological Research Jean Valery Mere Mfondoum Universite Toulouse 1 Capitole Toulouse School of Economics Mesmin Tchindjang Universite de Yaounde I Soa Hakdaoui Universite Mohammed V de Rabat Faculte des Sciences Ryan Cooper University of Texas at Dallas Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science Paul Gérard Gbetkom Aix-Marseille Universite - Campus Aix-en-Provence Schuman Joseph Penaye Institute of Mining and Geological Research Ateba Bekoa Institute of Mining and geological Research Cyriel Moudioh Institute of Mining and Geological Research Methodology Keywords: SLIP, DRIP, real-time mapping, geohazard, West-Cameroons’ Highlands, rainfall-triggered Landslides, Cox model, LHZ Posted Date: February 1st, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-19292/v4 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at Geoenvironmental Disasters on July 30th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-021-00189-9. Adapting the Sudden Landslide Identification Product (SLIP) and Detecting Real-Time Increased Precipitation (DRIP) algorithms to map rainfall-triggered landslides in the West- Cameroon highlands (Central-Africa) Alfred Homère Ngandam Mfondoum*1,2, Pauline Wokwenmendam Nguet3, Jean Valery Mefire Mfondoum4, Mesmin Tchindjang2, Sofia Hakdaoui 5, Ryan Cooper6 , Paul Gérard Gbetkom7, Joseph Penaye3, Ateba Bekoa3, Cyriel Moudioh3 Abstract Background – NASA’s developers recently proposed the Sudden Landslide Identification Product (SLIP) and Detecting Real-Time Increased Precipitation (DRIP) algorithms. -

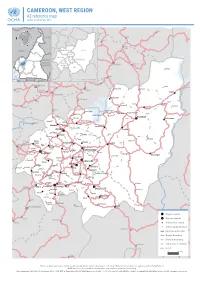

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 Reference Map Update of September 2018

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 reference map Update of September 2018 Nwa Ndu Benakuma CHAD WUM Nkor Tatum NIGERIA BAMBOUTOS NOUN FUNDONGMIFI MENOUA Elak NKOUNG-KHI CENTRAL H.-P. Njinikom AFRICAN HAUT- KUMBO Mbiame REPUBLIC -NKAM Belo NDÉ Manda Njikwa EQ. Bafut Jakiri GUINEA H.-P. : HAUTS--PLATEAUX GABON CONGO MBENGWI Babessi Nkwen Koula Koutoukpi Mabouo NDOP Andek Mankon Magba BAMENDA Bangourain Balikumbat Bali Foyet Manki II Bangambi Mahoua Batibo Santa Njimom Menfoung Koumengba Koupa Matapit Bamenyam Kouhouat Ngon Njitapon Kourom Kombou FOUMBAN Mévobo Malantouen Balepo Bamendjing Wabane Bagam Babadjou Galim Bati Bafemgha Kouoptamo Bamesso MBOUDA Koutaba Nzindong Batcham Banefo Bangang Bapi Matoufa Alou Fongo- Mancha Baleng -Tongo Bamougoum Foumbot FONTEM Bafou Nkong- Fongo- -Zem -Ndeng Penka- Bansoa BAFOUSSAM -Michel DSCHANG Momo Fotetsa Malânden Tessé Fossang Massangam Batchoum Bamendjou Fondonéra Fokoué BANDJOUN BAHAM Fombap Fomopéa Demdeng Singam Ngwatta Mokot Batié Bayangam Santchou Balé Fondanti Bandja Bangang Fokam Bamengui Mboébo Bangou Ndounko Baboate Balambo Balembo Banka Bamena Maloung Bana Melong Kekem Bapoungué BAFANG BANGANGTÉ Bankondji Batcha Mayakoue Banwa Bakou Bakong Fondjanti Bassamba Komako Koba Bazou Baré Boutcha- Fopwanga Bandounga -Fongam Magna NKONGSAMBA Ndobian Tonga Deuk Region capital Ebone Division capital Nkondjock Manjo Subdivision capital Other populated place Ndikiniméki InternationalBAF borderIA Region boundary DivisionKiiki boundary Nitoukou Subdivision boundary Road Ombessa Bokito Yingui The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. NOTE: In places, the subdivision boundaries may suffer of significant inacurracy. Date of update: 23/09/2018 ● Sources: NGA, OSM, WFP ● Projection: WGS84 Web Mercator ● Scale: 1 / 650 000 (on A3) ● Availlable online on www.humanitarianresponse.info ● www.ocha.un.org. -

Further Reading PARROT L

mep Laurent - Bologne:mep.DB 29/05/09 17:53 Page 1 Horticulture and city supply in Africa: evidence from South-West Cameroon RBAN growth in the West African coastal growth poles provides economies Laurent Parrot of scale and the urbanization process leads to agricultural transformation, Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche especially in terms of agricultural intensification. In this context, horticulture is Agronomique pour le Développement particularly well suited for an urban environment and for city supplies. (CIRAD), 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5, France Horticulture benefits from intensification techniques on small areas of Tel.: (334) 67-61-75-02 — fax: (334)-67-61-56-88 land and it provides good revenues for small scale farming systems. E-mail address: [email protected] NIGER NDJAMENA 0 200 km A Maroua I R E G I N Garoua MethodMuea was surveyed in August 1995 and again in June 2004 using Muea market and the main trade independent surveys. The surveys included a complete census of Ngaoundéré routes in Cameroon households (all houses and households were recorded for a random Oku Banso Bamenda Bali NdopFoumban Mamfe Mbouda CENTRAL selection), a household survey (300) and a market survey. Due to their Dschang Foumbot AFRICAN Bafoussam REPUBLIC nature and scope, the household and market surveys provided Muea Douala YAOUNDE Limbe complementary and cross-checked information. MALABO Edea EQUAT. GABON CONGO GUINEA Livestock & Food supplies Food supply Food & Manufacture supplies Main areas of demand Manufacture & Textile supplies Main trade flows Main paved roads The study of market flows among local food markets can be a good indicator of nationwide trade flows.