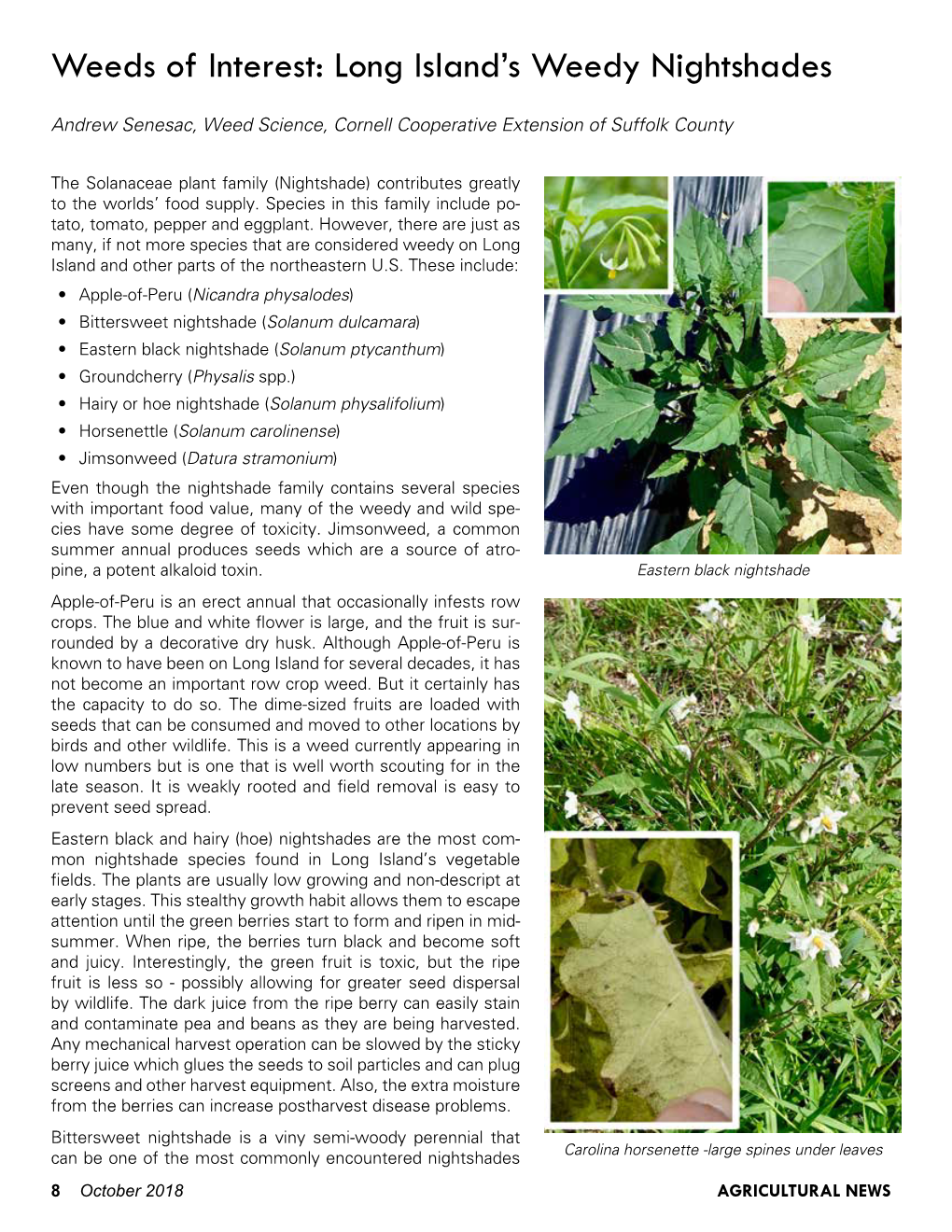

Weeds of Interest: Long Island's Weedy Nightshades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLANTS of the CURIMATAÚ PARAIBANO Valdeci F

FLORA OF PARAÍBA STATE – NORTHEASTERN BRAZIL 1 PLANTS OF THE CURIMATAÚ PARAIBANO Valdeci F. Sousa1, Carlos Alberto Garcia Santos1 & Leonardo M. Versieux2 1 Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Centro de Educação e Saúde, Cuité, PB, Brazil 2 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Departamento de Botânica, Ecologia e Zoologia, Natal, RN, Brazil Photos and Production: Valdeci F. Sousa. Pós-production: Juliana Philipp. © V.F. Sousa [[email protected]]. [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [776] version 1 11/2019 1 Justicia aequilabris 2 Justicia thunbergioides 3 Ruellia asperula 4 Ruellia bahiensis 5 Ruellia paniculata ACANTHACEAE ACANTHACEAE ACANTHACEAE ACANTHACEAE ACANTHACEAE 6 Hydrocleys martii 7 Copernicia prunifera 8 Aristolochia disticha 9 Pyrostegia venusta 10 Cordia trichotoma ALISMATACEAE ARECACEAE ARISTOLOCHIACEAE BIGNONIACEAE BORAGINACEAE 11 Euploca procumbens 12 Heliotropium elongatum 13 Myriopus rubicundus 14 Myriopus rubicundus 15 Varronia globosa BORAGINACEAE BORAGINACEAE BORAGINACEAE BORAGINACEAE BORAGINACEAE 16 Varronia globosa 17 Varronia leucocephala 18 Varronia dardani 19 Aechmea aquilega 20 Aechmea aquilega BORAGINACEAE BORAGINACEAE BORAGINACEAE BROMELIACEAE BROMELIACEAE FLORA OF PARAÍBA STATE – NORTHEASTERN BRAZIL PLANTS OF THE CURIMATAÚ PARAIBANO 2 Valdeci F. Sousa1, Carlos Alberto Garcia Santos1 & Leonardo M. Versieux2 1 Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Centro de Educação e Saúde, Cuité, PB, Brazil 2 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Departamento de Botânica, Ecologia e Zoologia, Natal, -

Physalis Peruviana Linnaeus, the Multiple Properties of a Highly Functional Fruit: a Review

Review Physalis peruviana Linnaeus, the multiple properties of a highly functional fruit: A review Luis A. Puente a,⁎, Claudia A. Pinto-Muñoz a, Eduardo S. Castro a, Misael Cortés b a Universidad de Chile, Departamento de Ciencia de los Alimentos y Tecnología Química. Av. Vicuña Mackenna 20, Casilla, Santiago, Chile b Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Departamento de Ingeniería Agrícola y de Alimento, A.A. 568 Medellin Colombia abstract The main objective of this work is to spread the physicochemical and nutritional characteristics of the Physalis peruviana L. fruit and the relation of their physiologically active components with beneficial effects on human health, through scientifically proven information. It also describes their optical and mechanical properties and presents micrographs of the complex microstructure of P. peruviana L. fruit and studies on the antioxidant Keywords: capacity of polyphenols present in this fruit. Physalis peruviana Bioactive compounds Functional food Physalins Withanolides Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................. 1733 2. Uses and medicinal properties of the fruit ................................................ 1734 3. Microstructural analysis ........................................................ 1734 4. Mechanical properties of the fruit .................................................... 1735 5. Optical properties of the fruit ...................................................... 1735 6. Antioxidant properties of fruit -

The Cape Gooseberry and the Mexican Husk Tomato

MORTON AND RUSSELL: CAPE GOOSEBERRY 261 LITERATURE CITED Seedling Plantings in Hawaii. Hawaii Agric. Expt. Sta. Bui. 79: 1-26. 1938. 1. Pope, W. T. The Macadamia Nut in Hawaii. 10. Howes, F. N. Nuts, Their Production and Hawaii Agric. Exp. Sta. Bui. 59: 1-23. 1929. Everyday Use. 264 pp. London, Faber & Faber. 2. Hamilton, R. A. and Storey, W. B. Macadamia 1953. Nut Varieties for Hawaii Orchards. Hawaii Farm Sci., 11. Cooil, Bruce J. Hawaii Agric. Exp. Sta. Bien 2: (4). 1954. nial Report—1950-52: p. 56. ft. Chell, Edwin and Morrison, F. R. The Cultiva 12. Beaumont, J. H. and Moltzau, R. H. Nursery tion and Exploitation of the Australian Nut. Sydney, Propagation and Topworking of the Macadamia. Ha Tech. Museum Bui. 20: 1935. waii Agric?. Exp. Sta. Cir. 13: 1-28. 1937. 4. Francis, W. D. Australian Rain Forest Trees. 13. Fukunaga. Edward T. Grafting and Topwork 469 pp. Sydney and London, Angus and Robertson: ing the Macadamia. Univ. of Hawaii Agric. Ext. Cir. 1951 58: 1-8. 1951. 5. Bailey, L. H. Manual of Cultivated Plants. N. Y.f 14. Storey, W. B., Hamilton, R. A. and Fukunaga, McMillan. 1949. E. T. The Relationship of Nodal Structures to Train 6. Chandler, Wm. H. Evergreen Orchards. 352 pp.: ing Macadamia Trees. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. Proc. 61: Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger. 1950. pp. 317-323. 1953. 7. Schroeder, C. A. The Macadamia Nut. Calif. 15. Anonymous. Insect Pests and Diseases of Agric, p. 3: April 1954. Plants. Queensland Agriculture and Pastoral Hand 8. Miller, Carey D. -

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species The first half of the color plates (Plates 1–8) shows a selection of phytochemically prominent solanaceous species, the second half (Plates 9–16) a selection of convol- vulaceous counterparts. The scientific name of the species in bold (for authorities see text and tables) may be followed (in brackets) by a frequently used though invalid synonym and/or a common name if existent. The next information refers to the habitus, origin/natural distribution, and – if applicable – cultivation. If more than one photograph is shown for a certain species there will be explanations for each of them. Finally, section numbers of the phytochemical Chapters 3–8 are given, where the respective species are discussed. The individually combined occurrence of sec- ondary metabolites from different structural classes characterizes every species. However, it has to be remembered that a small number of citations does not neces- sarily indicate a poorer secondary metabolism in a respective species compared with others; this may just be due to less studies being carried out. Solanaceae Plate 1a Anthocercis littorea (yellow tailflower): erect or rarely sprawling shrub (to 3 m); W- and SW-Australia; Sects. 3.1 / 3.4 Plate 1b, c Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade): erect herbaceous perennial plant (to 1.5 m); Europe to central Asia (naturalized: N-USA; cultivated as a medicinal plant); b fruiting twig; c flowers, unripe (green) and ripe (black) berries; Sects. 3.1 / 3.3.2 / 3.4 / 3.5 / 6.5.2 / 7.5.1 / 7.7.2 / 7.7.4.3 Plate 1d Brugmansia versicolor (angel’s trumpet): shrub or small tree (to 5 m); tropical parts of Ecuador west of the Andes (cultivated as an ornamental in tropical and subtropical regions); Sect. -

Of Physalis Longifolia in the U.S

The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review1 ,2 3 2 2 KELLY KINDSCHER* ,QUINN LONG ,STEVE CORBETT ,KIRSTEN BOSNAK , 2 4 5 HILLARY LORING ,MARK COHEN , AND BARBARA N. TIMMERMANN 2Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA 4Department of Surgery, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA 5Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review. The wild tomatillo, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related species have been important wild-harvested foods and medicinal plants. This paper reviews their traditional use as food and medicine; it also discusses taxonomic difficulties and provides information on recent medicinal chemistry discoveries within this and related species. Subtle morphological differences recognized by taxonomists to distinguish this species from closely related taxa can be confusing to botanists and ethnobotanists, and many of these differences are not considered to be important by indigenous people. Therefore, the food and medicinal uses reported here include information for P. longifolia, as well as uses for several related taxa found north of Mexico. The importance of wild Physalis species as food is reported by many tribes, and its long history of use is evidenced by frequent discovery in archaeological sites. These plants may have been cultivated, or “tended,” by Pueblo farmers and other tribes. The importance of this plant as medicine is made evident through its historical ethnobotanical use, information in recent literature on Physalis species pharmacology, and our Native Medicinal Plant Research Program’s recent discovery of 14 new natural products, some of which have potent anti-cancer activity. -

JABG01P351 Horton.Pdf

JOURNAL of the ADELAIDE BOTANIC GARDENS AN OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL FOR AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY flora.sa.gov.au/jabg Published by the STATE HERBARIUM OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA on behalf of the BOARD OF THE BOTANIC GARDENS AND STATE HERBARIUM © Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, South Australia © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia All rights reserved State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia J. Adelaide Bot Gard. 1(6): 351-356 (1979) TAXONOMIC ACCOUNT OF NICANDRA (SOLANACEAE) IN AUSTRALIA Philippa Horton Waite Agricultural Research Institute, University of Adelaide, P. Bag 1, Glen Osmond, South Australia 5064 Abstract Nicandra, of which there is only one species, N. physalodes (L.) Gaertn., is a native of Peru and has become naturalized in many tropical and temperate regions of the world. In Australia it is a weedy species occurring mainly in cleared or disturbed sites and on cultivated ground, mostly in the eastern coastal region. A description of the species based on Australian material is presented and its distribution in Australia is mapped. Introduction Nicandra physalodes, the only species in the genus (family Solanaceae) and nativeto Peru, has become a well-established member of the Australian flora. It has been cultivatedas an ornamental garden plant in Australia and elsewhere, and is now widely dispersed in tropical and temperate areas. N. physalodes has been suspected of poisoning stock, but feeding experiments in New South Wales in which thegreen berries and the plant were tested on sheep and a goat gave negative results (Hurst, 1942). -

Solanum Elaeagnifolium Cav. R.J

R.A. Stanton J.W. Heap Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. R.J. Carter H. Wu Name Lower leaves c. 10 × 4 cm, oblong-lanceolate, distinctly sinuate-undulate, upper leaves smaller, Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. is commonly known oblong, entire, venation usually prominent in in Australia as silverleaf nightshade. Solanum is dried specimens, base rounded or cuneate, apex from the Latin solamen, ‘solace’ or ‘comfort’, in acute or obtuse; petiole 0.5–2 cm long, with reference to the narcotic effects of some Solanum or without prickles. Inflorescence a few (1–4)- species. The species name, elaeagnifolium, is flowered raceme at first terminal, soon lateral; Latin for ‘leaves like Elaeagnus’, in reference peduncle 0.5–1 cm long; floral rachis 2–3 cm to olive-like shrubs in the family Elaeagnaceae. long; pedicels 1 cm long at anthesis, reflexed ‘Silverleaf’ refers to the silvery appearance of and lengthened to 2–3 cm long in fruit. Calyx the leaves and ‘nightshade’ is derived from the c. 1 cm long at anthesis; tube 5 mm long, more Anglo-Saxon name for nightshades, ‘nihtscada’ or less 5-ribbed by nerves of 5 subulate lobes, (Parsons and Cuthbertson 1992). Other vernacu- whole enlarging in fruit. Corolla 2–3 cm diam- lar names are meloncillo del campo, tomatillo, eter, rotate-stellate, often reflexed, blue, rarely white horsenettle, bullnettle, silver-leaf horsenet- pale blue, white, deep purple, or pinkish. Anthers tle, tomato weed, sand brier, trompillo, melon- 5–8 mm long, slender, tapered towards apex, cillo, revienta caballo, silver-leaf nettle, purple yellow, conspicuous, erect, not coherent; fila- nightshade, white-weed, western horsenettle, ments 3–4 mm long. -

Tomatillo Cheryl Kaiser1 and Matt Ernst2 Introduction Tomatillo (Physalis Ixocarp) Is a Small Edible Fruit in the Solanaceae Family

Center for Crop Diversification Crop Profile Tomatillo Cheryl Kaiser1 and Matt Ernst2 Introduction Tomatillo (Physalis ixocarp) is a small edible fruit in the Solanaceae family. A tan to straw-colored calyx covers the fruit-like a husk, giving rise to the common name of “husk tomato.” Native to Mexico and Guatemala, these tomato-like fruits are a key ingredient in a number of Latin American recipes, including salsa and chili sauces. Tomatillo may have potential as a specialty crop in some areas of Kentucky. Marketing Tomatillos are sold by Kentucky farms through direct marketing channels, including farmers markets, CSAs and roadside stands. Market potential may be greater at farmers markets in areas with larger Hispanic increasing U.S. Hispanic populations. Local groceries, as well as restaurants population helped establish specializing in Mexican or vegetarian dishes, may tomatillo as a nationwide be interested in purchasing locally grown tomatillos. commodity within wholesale produce marketing Production of tomatillo for direct sale to smaller channels. Producers considering growing tomatillo specialty food manufacturers, or for use in foods will likely have more success with fresh market prepared by the producer, may also be an option for Kentucky growers. retail sales in larger urban areas such as Louisville, Lexington, or Cincinnati. Novel or distinctive Large-scale production requires accessing wholesale tomatillos, such as varieties with purple coloration, marketing channels. Most fresh market shipments could be offered alongside classic green tomatillos; are sourced from Mexico and California; Florida and however, producers should identify the preferences Michigan also ship through the commercial fresh of potential customers, as some may prefer certain market in the summer. -

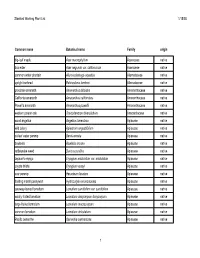

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

The Complete Genome Sequence, Occurrence and Host Range Of

Li et al. Virology Journal (2017) 14:15 DOI 10.1186/s12985-016-0676-2 RESEARCH Open Access The complete genome sequence, occurrence and host range of Tomato mottle mosaic virus Chinese isolate Yueyue Li1†, Yang Wang1†, John Hu2, Long Xiao1, Guanlin Tan1,3, Pingxiu Lan1, Yong Liu4* and Fan Li1* Abstract Background: Tomato mottle mosaic virus (ToMMV) is a recently identified species in the genus Tobamovirus and was first reported from a greenhouse tomato sample collected in Mexico in 2013. In August 2013, ToMMV was detected on peppers (Capsicum spp.) in China. However, little is known about the molecular and biological characteristics of ToMMV. Methods: Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and rapid identification of cDNA ends (RACE) were carried out to obtain the complete genomic sequences of ToMMV. Sap transmission was used to test the host range and pathogenicity of ToMMV. Results: The full-length genomes of two ToMMV isolates infecting peppers in Yunnan Province and Tibet Autonomous Region of China were determined and analyzed. The complete genomic sequences of both ToMMV isolates consisted of 6399 nucleotides and contained four open reading frames (ORFs) encoding 126, 183, 30 and 18 kDa proteins from the 5’ to 3’ end, respectively. Overall similarities of the ToMMV genome sequence to those of the other tobamoviruses available in GenBank ranged from 49.6% to 84.3%. Phylogenetic analyses of the sequences of full-genome nucleotide and the amino acids of its four proteins confirmed that ToMMV was most closely related to Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV). According to the genetic structure, host of origin and phylogenetic relationships, the available 32 tobamoviruses could be divided into at least eight subgroups based on the host plant family they infect: Solanaceae-, Brassicaceae-, Cactaceae-, Apocynaceae-, Cucurbitaceae-, Malvaceae-, Leguminosae-, and Passifloraceae-infecting subgroups. -

Potato Update Issue 3

July 2014 Potato Update Issue 3 Non-crop host plants of tomato potato psyllid in New Zealand What is a host plant? A host plant is a plant on which TPP completes its full lifecycle from egg through to adult. Key points What crops are host plants of TPP? • Tomato potato psyllid (TPP) Crops belonging to the Solanaceae and Convolvulaceae family, which can complete its lifecycle includes potatoes, tomatoes, capsicums, chilli peppers, goji berries, on a number of crop and tamarillos, eggplant, tobacco, kumara/sweet potato and taewa/Māori non-crop plants. potatoes. • Some non-crop host plants can provide a host for TPP all year round even in frost Why do you need to be aware of non-crop host prone areas. plants of TPP? Some of the species described below such as African boxthorn, Jerusalem cherry and Poroporo have all life stages of TPP on them all year round. This is the case for all of New Zealand, even frosty areas. This means that whether you have a crop in the ground or have harvested your crop and it is the middle of winter, TPP are potentially surviving and breeding on non-crop plants in or near your crop. Non-crop host plants in New Zealand Following is a list of the most important host plants that may be present around your potato crop. Common name: African boxthorn Botanical name: Lycium ferocissimum Description: Evergreen perennial. Chinese boxthorn is similar but is deciduous. Distribution: Throughout New Zealand, predominantly in coastal areas. Photo: John Barkla. Photo: Anna-Marie Barnes. Common name: Poroporo Botanical name: Solanum laciniatum or S. -

Quick Scan Tomato Mottle Mosaic Virus

Quick scan National Plant Protection Organization, the Netherlands Quick scan number: 2020VIR001 Quick scan date: 4 November 2020 No. Question Quick scan answer for Tomato mottle mosaic virus 1. What is the scientific name (if Tomato mottle mosaic virus (ToMMV), genus Tobamovirus, family Virgaviridae possible up to species level + author, also include (sub)family and order) and English/common name of the organism? Add picture of organism/damage if available and publication allowed. 2. What prompted this quick scan? ToMMV is (currently) not regulated in the EU. For the related tobamovirus tomato brown rugose fruit virus Organism detected in produce for (ToBRFV), however, emergency measures have been in place since November 2019 (EU, 2019 and 2020). import, export, in cultivation, ToBRFV has been found causing damage to tomato and pepper crops in the EU since it is able to nature, mentioned in publications, overcome resistances of current cultivars (Luria et al., 2017). The fact that ToMMV shares characteristics e.g. EPPO alert list, etc. with ToBRFV (Li et al., 2017), is reason for drafting this quick scan. In addition, Australia has implemented emergency measures for ToMMV and requires tomato and pepper seed lots to be imported, to be tested and found free from this virus (https://www.agriculture.gov.au/import/goods/plant- products/seeds-for-sowing/emergency-measures-tommv-qa#what-is-tomato-mottle-mosaic-virus- tommv). 3. What is the current area of CABI distribution map, retrieved 7-7-2020, 11-6-2020 distribution? Pagina 1 van 6 No. Question Quick scan answer for Tomato mottle mosaic virus Present in Asia: China (Li et al., 2014), Iran, Israel (Turina et al., 2016) Europe: Spain (Ambros et al., 2017) America: Brasil (Nagai et al., 2018) Mexico (Li et al., 2013) USA (Webster et al., 2014) ToMMV may have a wider distribution than currently known.