In the Crosshairs: How Systemic Racism Compelled Interstate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 6 Number 1 2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy L. Draeger-Williams, Archaeologist Wade T. Tharp, Archaeologist Rachel A. Sharkey, Records Check Coordinator Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D. Amy L. Johnson Cathy A. Carson Editorial Assistance: Cathy Draeger-Williams Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service is gratefully acknow- ledged for their support of Indiana archaeological research as well as this volume. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. This publication has been funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service‘s Historic Preservation Fund administered by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. In addition, the projects discussed in several of the articles received federal financial assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund Program for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the State of Indiana. -

Black History News & Notes

BLACK HISTORY NEWS & NOTES INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY February, 1982 No. 8 ) Black History Now A Year-round Celebration A new awareness of black history was brought forth in 1926 when Carter Woodson in augurated Negro History Week. Since that time the annual celebration of Afro-American heritage has grown to encompass the entire month of February. Now, with impetus from concerned individuals statewide, Indiana residents are beginning to witness what hope fully will become a year-round celebration of black history. During the weeks and months immediately ahead a number of black history events have been scheduled. The following is a description of some of the activities that will highlight the next three months. Gaines to Speak Feb. 2 8 An Afro-American history lecture by writer Ernest J. Gaines on February 28 is T H E A T E R Indiana Av«. being sponsored by the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library (I-MCPL). Gaines BIG MIDNITE RAMBLE is the author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and several other works ON OUR STAGE pertaining to the black experience. The lecture will be held at 2:00 P.M. at St. Saturday Night Peter Claver Center, 3110 Sutherland Ave OF THIS WEEK nue. Following the event, which is free DECEMBER 15 1UW l\ M. and open to the public, Gaines will hold Harriet Calloway an autographing session. Additional Black QUEEN OF HI DE HO History Month programs and displays are IN offered by I-MCPL. For further informa tion call (317) 269-1700. DIXIE ON PARADE W ITH George Dewey Washington “Generations” Set for March Danny and Eddy FOUH PENNIES COOK and BROWN A national conference will be held JENNY DANCER FLORENCE EDMONDSON in Indianapolis March 25-27 focusing on SHORTY BURCH FRANK “Red” PERKINS American family life. -

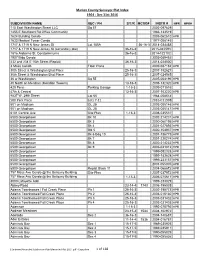

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave -

William H. Hudnut III Collection L523

William H. Hudnut III collection L523 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 17, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books and Manuscripts 140 North Senate Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana, 46204 317-232-3671 William H. Hudnut III collection L523 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Series 1: Correspondence and general papers, 1969-1974..................................................................... 8 Series 2: Watergate papers, 1971-1974...............................................................................................103 -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 (7-B1) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Lockefield Garden Apartments and/or common Lockefield Gardens 2. Location street & number 900 Indiana Aventrer not for publication city, town Indi anapol i s vicinity of state Indiana code 0] 8 county Marion codeQ97 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A AY no military JL_ other: Vacant 4. Owner of Property name Indianapolis Housing Authority street & number 410 N. Meridian Street city, town Indianapolis vicinity of state Indiana 46204 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Center Township Assessor street & number 1321 City-County Building city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 46204 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Preservation Work Paper, Regional title Center Plan. Indianapolis__________has this property been determined eligible? _X_yes no date January, 1981 J£_ federal state county local depository for survey records Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission city, town Indianapolis state Indiana (continued) 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original site good ruins altered moved date N/A J£_fair unex posed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Lockefield Gardens is located on a superb!ock bounded by Indiana Avenue on the north, Blake Street on the east, North Street on the south and Locke Street on the west. -

Download This

NPSForm 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior ,1U*-*J National Park Service MAY 1 4 20G8 j£T C *£•- National Register of Historic Places NA1[REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_____________________________________________________ historic name North Irvington Gardens Historic District______________________________ other names/site number __________________________________________________ 2. Location & number See continuation sheets N/A Q not for publication city or town ___Indianapolis______ N/A D vicinity state Indiana code IN county Marion code 097 zip code 46219 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Pres ervation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this QD nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documeritation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional r equirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property El meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

SAGAMORE INDIANAPOLIS T Feb

THE WEEKLY NEWSPAPER OF INDIANA UNIVERSITY-PURDUE UNIVERSITY AT The SAGAMORE INDIANAPOLIS T_ Feb. 20. 1989 Vol. 18, No. 26 THIS WEEK Olympic center Students defend delayed until 1990 dorm front By JEFFREY DellERDT Still, students may encounter By CHRIS FLECK athletes by mid-March if the IUPUI’s Olympic flag may be USOC approves Indianapolis as With their collective eye on an further on the horizon than first one of four designated Olympic Olympic training center, campus planned. training centers. administrators don't want their “We will make the transition The official designation will aim to suffer. over 18 months, not 9 months, have been made during the “We're not going to shoot oyr- as we said before,” said Robert USOC meeting Feb. 18-19 in selves in the foot," said Robert E. Baxter, special assistant to Portland, Ore., at which details E. Baxter, special assistant to IUPU1 Chancellor Gerald Bepko and some time tables of changes Chancellor Gerald Bepko, refer and IUPUI’s representative in to be made to the IUPUI campus nng to the proposed abrupt negotiations. may bo finalized. relocation of Warthin Apart *Even if they (the United “We have a 99 percent chance ment residents to other un States Olympic Committee) of keeping the permanent desig designated facilities because of came to the table right now with nation,” said Baxter. But, Bax the planned Olympic center. all the funds, we would still wait ter said he will not know exact During a three hour meeting until then,” said Baxter. time tables until much later. -

Help for Historic Houses of Worship

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2016 Sacred Ground Help for Historic Houses of Worship HOPE FOR TOMORROW Plan for Chicago landmark in Indiana Dunes JUST IN TIME Restoring the Ayres clock FROM THE PRESIDENT STARTERS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Eli Lilly (1885-1977), Founder OFFICERS Cheri Dick Zionsville LANDMARK LEXICON Hon. Randall T. Shepard Honorary Chairman Julie Donnell Fort Wayne James P. Fadely Chairman Jeremy D. Efroymson How Rood One Woman’s Legacy Indianapolis Carl A. Cook Past Chairman Gregory S. Fehribach NO, NOT “RUDE” BUT “ROOD,” Indianapolis LAST YEAR, LONG-TIME Parker Beauchamp an archaic word for crucifix. In Vice Chairman Sanford E. Garner Indiana Landmarks member Zelpha Indianapolis late medieval church architec- Marsh Davis Mitsch passed away. Zelpha was a val- President Judith A. Kanne ture, a rood screen separated Rensselaer ued member of our Heritage Society, Sara Edgerton the nave, where the congre- Secretary/Assistant Treasurer Christine H. Keck Evansville a group of people who have made pro- Thomas H. Engle gation sat, from the altar in visions to support Indiana Landmarks’ Assistant Secretary Matthew R. Mayol, AIA the chancel, where the clergy Indianapolis Brett D. McKamey mission through estate planning. Her Treasurer Sharon Negele sat. The openwork screen, Attica bequest of hundreds of acres of farm- H. Roll McLaughlin, FAIA sometimes elaborately carved, Chairman Emeritus Cheryl Griffith Nichols land in Floyd and Harrison counties Little Rock, AR always incorporated a cross or Judy A. O’Bannon © VISIT MORGAN COUNTY promises to be among the largest gifts Secretary Emerita Martin E. Rahe backed a hanging crucifix. In Cincinnati, OH this organization has received. -

Task 4/6 Report: Programming & Destinations

Tasks Four/Six: Destinations and Programming In these tasks, the team developed an understanding for destinations, events, programming, and gathering places along the White River. The team evaluated existing and potential destinations in both Hamilton and Marion Counties, and recommended new catalyst sites and destinations along the River. The following pages detail our process and understanding of important destinations for enhanced or new protection, preservation, programming and activation for the river. Core Team DEPARTMENT OF METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT HAMILTON COUNTY TOURISM, INC. VISIT INDY RECONNECTING TO OUR WATERWAYS Project Team AGENCY LANDSCAPE + PLANNING APPLIED ECOLOGICAL SERVICES, INC. CHRISTOPHER B. BURKE ENGINEERING ENGAGING SOLUTIONS FINELINE GRAPHICS HERITAGE STRATEGIES HR&A ADVISORS, INC. LANDSTORY LAND COLLECTIVE PORCH LIGHT PROJECT PHOTO DOCS RATIO ARCHITECTS SHREWSBERRY TASK FOUR/SIX: DESTINATIONS AND PROGRAMMING Table of Contents Destinations 4 Programming 18 Strawtown Koteewi 22 Downtown Noblesville 26 Allisonville Stretch 30 Oliver’s Crossing 34 Broad Ripple Village 38 Downtown Indianapolis 42 Southwestway Park 46 Historic Review 50 4 Destinations Opportunities to invest in catalytic projects exist all along the 58-mile stretch of the White River. Working together with the client team and the public, the vision plan identified twenty-seven opportunity sites for preservation, activation, enhancements, or protection. The sites identified on the map at right include existing catalysts, places that exist but could be enhanced, and opportunities for future catalysts. All of these are places along the river where a variety of experiences can be created or expanded. This long list of destinations or opportunity sites is organized by the five discovery themes. Certain locations showed clear overlap among multiple themes and enabled the plan to filter through the long list to identify seven final sites to explore as plan ‘focus areas’ or ‘anchors’. -

Download PDF Success Story

SUCCESS STORY New Deal Public Housing Gets New Life Indianapolis, Indiana THE STORY During the New Deal, the Public Works Administration launched a program of federal public housing projects to provide needed low-cost housing. One of the first projects, Lockefield Gardens, was designed to maintain the spirit and vitality of its constituent “When Lockefield was built, African American community while offering a modern, modestly priced place to live. it became a source of pride Completed in1936, it became a national model for high design standards, superior construction quality, and innovative landscaping techniques. The federal government and of hope for the local transferred the property to the City of Indianapolis in 1964 with a deed stipulation that it community...” would be used for public housing until 2004 or would revert to the federal government. —NaTIONAL REGISTER THE PROJECT NOMINATION In the 1970s, the City proposed demolishing the housing project using federal funds to 1983 expand campus housing for Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI). The City claimed Lockefield Gardens had declined in quality, and other housing options for low-income residents existed. As a result, the apartments officially closed in 1976. However, the City could not proceed unless the reversionary clause was waived and the use of federal funds was approved for demolition. THE 106 PROCESS The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the federal agency authorized to approve the waiver and use of federal funds, was responsible for conducting the Section 106 process under the National Historic Preservation Act. Section 106 requires that federal agencies identify historic properties and assess the effects of the projects they carry out, fund, or permit on those properties. -

Recent Articles, Pamphlets, and Dissertations in Indiana History

Recent Articles, Pamphlets, and Dissertations in Indiana History Editor’s Note. This list of articles, pamphlets, and dissertations published in 1980 and 1981 is intended as a bibliographic contribution to Indiana’s history. As our first list of this kind, it is neither complete nor systematic in coverage. With this first effort as an experiment we hope to be able to present a list in each March issue of the Indiana Magazine of History. Readers can help in this objective by sending items for possible inclu- sion. We are especially interested in listing publications that make some contribution to understanding Indiana’s past but are not normally reviewed in the IMH. Generally, we will not list newspaper articles or accounts of local historical society activities (which are reported in the Indiana History Bulletin), but printed pamphlets as well as journal articles may be listed. All such items for the March, 1983, issue must be received by December 1, 1982. Many people have contributed to the present list, but major responsibility has rested with Robert G. Barrows of the Indiana Historical Bureau and Gary L. Bailey of the Indiana Magazine of History. Austin, Penelope Canan, “Federal Presence in Middletown: 1937-1977,” [Middletown I11 Project, Paper No. 91 Tocque- ville Review, I1 (Spring-Summer, 1980). Bahr, Howard M., Theodore Caplow, and Geoffrey K. Leigh, “Slowing of Modernization in Middletown,” [ Middletown I11 Project, Paper No. 141 Research in Social Movements, Con- flicts and Change, I11 (1980). Barger, Harry, “Pioneer Medicine,” Old Fort News, XLIV (No. 2, 1981). Baron, James N. “Indianapolis and Beyond: A Structural Model of Occupational Mobility across Generations,” American Journal of Sociology, LXXXV (January, 1980). -

Indiana Avenue Paul Mullins

Indiana Avenue Paul Mullins Paul Mullins November 20, 2020 Published online at https://indyencyclopedia.org/ features/indiana-avenue/ © 2021 Indianapolis Public Library Contents Indiana Avenue in the 19th century 1 Segregating the Avenue 4 The Avenue’s Underground Economy 6 African American Expressive Culture 10 Urban Renewal 19 Mrs. Shelly’s Boarding House in 1882. The boarding house was Indiana Avenue in the 19th century located across the street from In the 1820s Indiana Avenue was not much more than a dirt path that Leonard Schurr’s jewelry store. existed in cartographical imagination more than as a central thorough- Boarding houses like this were fare, and it would mostly stand empty into the middle of the 19th cen- common along the Avenue. tury. Prior to the 1850’s the undeveloped land on the city’s northwest Source: Indiana Album. side was often used for horse races that “took place nearly every Satur- day, and were usually decorated with a fight or two,” according to Barry R. Sulgrove. Indianapolis grew slowly until the 1850s. Indiana’s largest cities were New Albany and Madison, where the Ohio River facilitat- ed trade. In Indianapolis, the White River was unnavigable, and the planned Central Canal failed in 1939. While the newly built National Road (Washington Street) provided a slightly improved artery for trade, there simply was no reliable way to bring goods to the city or transport them to external markets. During this period W.R. Holloway noted that “business was entirely of a local character. Manufacturing was merely for home consumption.” 1 Early European settlers Some of the city’s earliest European settlers farmed along the north- western reaches of Indiana Avenue and operated mills on the tributaries of Fall Creek.