49.1992.1 Crispus Attucks High School Marion County Marker Text Review Report 03/05/2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, Or the Legacy of Ishmael

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Faculty Publications Department of English 2012 From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael Elizabeth J. West Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation West, Elizabeth J., "From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael" (2012). English Faculty Publications. 15. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_facpub/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “From David Walker to President Obama: Tropes of the Founding Fathers in African American Discourses of Democracy, or The Legacy of Ishmael” Dr. Elizabeth J. West Dept. of English—Georgia State Univ. Nov. 2010 “Call me Ishmael,” Herman Melville’s elusive narrator instructs readers. The central voice in the lengthy saga called Moby Dick, he is a crewman aboard the Pequod. This Ishmael reveals little about himself, and he does not seem altogether at home. As the narrative unfolds, this enigmatic Ishmael seems increasingly out of sorts in the world aboard the Pequod. He finds himself at sea working with and dependent on fellow seamen, who are for the most part, strange and frightening and unreadable to him. -

The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: Theater/ Words by Penny Neef

Spotlight: The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: http://spotlightnews.press/index.php/2020/09/04/spotlight-the-attucks- theater/ Words by Penny Neef. Images as credited. Feature image by Mike Penello. In the early 20th century, segregation was a fact of life for African Americans in the South. It became a matter of law in 1926. In 1919, a group of African Americans from Norfolk and Portsmouth met to develop a cultural/business center in Norfolk where the black community “could be treated with dignity and respect.” The “Twin Cities Amusement Corporation” envisioned something like a modern-day town center. The businessmen obtained funding from black owned financial institutions in Hampton Roads. Twin Cities designed and built a movie theater/ retail/ office complex at the corner of Church Street and Virginia Beach Boulevard in Norfolk. Photo courtesy of the family of Harvey Johnson The businessmen chose 25-year-old architect Harvey Johnson to design a 600-seat “state of the art” theater with balconies and an orchestra pit. The Attucks Theatre is the only surviving theater in the United States that was designed, financed and built by African Americans. The Attucks was named after Crispus Attucks, a stevedore of African and Native American descent. He was the first patriot killed in the Revolutionary War at the Boston Massacre of 1770. The theatre featured a stage curtain with a dramatic depiction of the death of Crispus Attucks. Photo by Scott Wertz. The Attucks was an immediate success. It was known as the “Apollo Theatre of the South.” Legendary performers Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Nat King Cole, and B.B. -

BLACK HISTORY – PERTH AMBOY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Black History in Kindergarten

BLACK HISTORY – PERTH AMBOY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Black History in Kindergarten Read and Discuss and Act out: The Life's Contributions of: Ruby Bridges Bill Cosby Rosa Parks Booker T. Washington Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Jackie Robinson Louie Armstrong Wilma Rudolph Harriet Tubman Duke Ellington Black History in 1st Grade African Americans Read, Discuss, and Write about: Elijah McCoy, Booker T. Washington George Washington Carver Mathew Alexander Henson Black History in 2nd Grade Select an African American Leader Students select a partner to work with; What would you like to learn about their life? When and where were they born? Biography What accomplishments did they achieve in their life? Write 4-5 paragraphs about this person’s life Black History 3rd & 4th Graders Select a leader from the list and complete a short Biography Black History pioneer Carter Godwin Woodson Boston Massacre figure Crispus Attucks Underground Railroad leader Harriet Tubman Orator Frederick Douglass Freed slave Denmark Vesey Antislavery activist Sojourner Truth 'Back to Africa' leader Marcus Garvey Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad Legal figure Homer Plessy NAACP founder W. E. B. Du Bois Murdered civil rights activist Medgar Evers Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Civil rights leader Coretta Scott King Bus-riding activist Rosa Parks Lynching victim Emmett Till Black History 3rd & 4th Graders 'Black Power' advocate Malcolm X Black Panthers founder Huey Newton Educator Booker T. Washington Soul On Ice author Eldridge Cleaver Educator Mary McLeod Bethune Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall Colonial scientist Benjamin Banneker Blood bank pioneer Charles Drew Peanut genius George Washington Carver Arctic explorer Matthew Henson Daring flier Bessie Coleman Astronaut Guion Bluford Astronaut Mae Jemison Computer scientist Philip Emeagwali Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai Black History 3rd & 4th Graders Brain surgeon Ben Carson U.S. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 6 Number 1 2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy L. Draeger-Williams, Archaeologist Wade T. Tharp, Archaeologist Rachel A. Sharkey, Records Check Coordinator Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D. Amy L. Johnson Cathy A. Carson Editorial Assistance: Cathy Draeger-Williams Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service is gratefully acknow- ledged for their support of Indiana archaeological research as well as this volume. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. This publication has been funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service‘s Historic Preservation Fund administered by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. In addition, the projects discussed in several of the articles received federal financial assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund Program for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the State of Indiana. -

Black History News & Notes

BLACK HISTORY NEWS & NOTES INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY February, 1982 No. 8 ) Black History Now A Year-round Celebration A new awareness of black history was brought forth in 1926 when Carter Woodson in augurated Negro History Week. Since that time the annual celebration of Afro-American heritage has grown to encompass the entire month of February. Now, with impetus from concerned individuals statewide, Indiana residents are beginning to witness what hope fully will become a year-round celebration of black history. During the weeks and months immediately ahead a number of black history events have been scheduled. The following is a description of some of the activities that will highlight the next three months. Gaines to Speak Feb. 2 8 An Afro-American history lecture by writer Ernest J. Gaines on February 28 is T H E A T E R Indiana Av«. being sponsored by the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library (I-MCPL). Gaines BIG MIDNITE RAMBLE is the author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and several other works ON OUR STAGE pertaining to the black experience. The lecture will be held at 2:00 P.M. at St. Saturday Night Peter Claver Center, 3110 Sutherland Ave OF THIS WEEK nue. Following the event, which is free DECEMBER 15 1UW l\ M. and open to the public, Gaines will hold Harriet Calloway an autographing session. Additional Black QUEEN OF HI DE HO History Month programs and displays are IN offered by I-MCPL. For further informa tion call (317) 269-1700. DIXIE ON PARADE W ITH George Dewey Washington “Generations” Set for March Danny and Eddy FOUH PENNIES COOK and BROWN A national conference will be held JENNY DANCER FLORENCE EDMONDSON in Indianapolis March 25-27 focusing on SHORTY BURCH FRANK “Red” PERKINS American family life. -

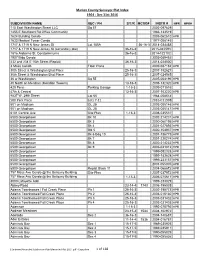

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave -

Emma Lou Thornbrough Manuscript, Ca 1994

Collection # M 1131 EMMA LOU THORNBROUGH MANUSCRIPT, CA 1994 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Kelsey Bawel 26 August 2014 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1 document case COLLECTION: COLLECTION ca. 1994 DATES: PROVENANCE: RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2007.0085 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Emma Lou Thornbrough (1913-1994), an Indianapolis native, graduated from Butler University with both a B.A. and an M.A. She went on to the University of Michigan where she received her Ph.D. in 1946. Following graduation, Thornbrough began teaching at Butler until her retirement in 1983. During her career at Butler, she held visiting appointments at Indiana University and Case Western Reserve University. Thornbrough’s research is exemplified in her two main works: The Negro in Indiana before 1900 (1957) and Indiana in the Civil War (1965). She engaged the community by writing numerous articles focusing on United States constitutional history and race as a central force in the nation’s development. Thornbrough was also active in various community organizations including the Organization of American Historians, Southern Historical Association, Indiana Historical Society, Indiana Association of Historians, Indiana Alpha Association of Phi Beta Kappa, American Association of University Professors, Indiana Civil Liberties Union, Indianapolis Council of World Affairs, Indianapolis NAACP, and the Indianapolis Human Relations Council. -

2011/2012 Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions # CATEGORY

2011/2012 Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions # CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER Along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, what type of music is played 1 Arts with the accordion? Zydeco 2 Arts Who wrote "Their Eyes Were Watching God" ? Zora Neale Hurston Which one of composer/pianist Anthony Davis' operas premiered in Philadelphia in 1985 and was performed by the X: The Life and Times of 3 Arts New York City Opera in 1986? Malcolm X Since 1987, who has held the position of director of jazz at 4 Arts Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City? Wynton Marsalis Of what profession were Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Countee Cullen, major contributors to the Harlem 5 Arts Renaissance? Writers Who wrote Clotel , or The President’s Daughter , the first 6 Arts published novel by a Black American in 1833? William Wells Brown Who published The Escape , the first play written by a Black 7 Arts American? William Wells Brown 8 Arts What is the given name of blues great W.C. Handy? William Christopher Handy What aspiring fiction writer, journalist, and Hopkinsville native, served as editor of three African American weeklies: the Indianapolis Recorder , the Freeman , and the Indianapolis William Alexander 9 Arts Ledger ? Chambers 10 Arts Nat Love wrote what kind of stories? Westerns Cartoonist Morrie Turner created what world famous syndicated 11 Arts comic strip? Wee Pals Who was born in Florence, Alabama in 1873 and is called 12 Arts “Father of the Blues”? WC Handy Georgia Douglas Johnson was a poet during the Harlem Renaissance era. -

Crispus Attucks Museum Unit #3: School Segregation and Desegregation of Indianapolis Public Schools Grades:Grade 11/ Subject: U.S

Crispus Attucks Museum Unit #3: School Segregation and Desegregation of Indianapolis Public Schools Grades:Grade 11/ Subject: U.S. Teacher: Grade 12 History/U.S. Government Duration: 30 minutes (each) Day(s) 1 Lesson #: 1 of 2 Standards: Grade 11 – U.S. History after 1877 USH.6.2 Summarize and assess the various actions which characterized the early struggle for civil rights (1945-1960). USH.6.3 Describe the constitutional significance and lasting societal effects of the United States Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case. USH.6.4 Summarize key economic and social changes in post-WW II American life. USH.9.1 Identify patterns of historical succession and duration in which historical events have unfolded and apply them to explain continuity and change. USH.9.2 Locate and analyze primary sources and secondary sources related to an event or issue of the past; discover possible limitations in various kinds of historical evidence and differing secondary opinions. USH.9.4 Explain issues and problems of the past by analyzing the interests and viewpoints of those involved. Grade 12 – U.S. Government USG.1.9 Evaluate how the United States Constitution establishes majority rule while protecting minority rights and balances the common good with individual liberties. USG.2.8 Explain the history and provide historical and contemporary examples of fundamental principles and values of American political and civic life, including liberty, security, the common good, justice, equality, law and order, rights of individuals, diversity, popular sovereignty, and representative democracy. USG.5.2 Analyze the roles and responsibilities of citizens in Indiana and the United States. -

William H. Hudnut III Collection L523

William H. Hudnut III collection L523 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 17, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books and Manuscripts 140 North Senate Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana, 46204 317-232-3671 William H. Hudnut III collection L523 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Series 1: Correspondence and general papers, 1969-1974..................................................................... 8 Series 2: Watergate papers, 1971-1974...............................................................................................103 -

We a Dream 1776 1976

We Had A Dream 1776 1976 Contributions of Black Americans Author and Editor- Vernon C. Lawhorn + II1II Additional methods can be used to further educate students about this mural. We Had a Dream 1776-1976 No. 1. This material can be used to enhance biographical work of historic figures. Contributions of Black Americans No.2. The material will readily lend itself to standard testing procedures, such as True or False, Multiple Choice, Matching Fill-Ins and Essays. No.3. This Visual material will aid the student in his or her effort to compare and contrast current events with the past or historical occurences. No.4. It could be useful in understanding the borrowing and synthe- The subjects of this painting are both male and female, encompassing sizing that occurs in the birth and development of movements. Dr. Martin virtually all aspects of the American Experience. Luther King, Jr. borrowed from Mahatma Gandi; Ceasar Chavez, the No. 1. It is a history in color of the Black experience in America. It's Mexican American who now still marches and protests against a system first figure is that of an African Mask: It's final figure is a Red, Black & that deprives his people their freedom and rights, from Dr. King. Green flag, symbolic of the desire by blacks to understand and relate to their African Heritage. In summation, the question is, who would benefit? NOTE: The African Mask is symbolic of the origin of American Blacks. No.2. Some of the individuals in the painting are anonymous but most . Multiculture is apparently the wave of the future. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 (7-B1) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Lockefield Garden Apartments and/or common Lockefield Gardens 2. Location street & number 900 Indiana Aventrer not for publication city, town Indi anapol i s vicinity of state Indiana code 0] 8 county Marion codeQ97 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A AY no military JL_ other: Vacant 4. Owner of Property name Indianapolis Housing Authority street & number 410 N. Meridian Street city, town Indianapolis vicinity of state Indiana 46204 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Center Township Assessor street & number 1321 City-County Building city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 46204 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Preservation Work Paper, Regional title Center Plan. Indianapolis__________has this property been determined eligible? _X_yes no date January, 1981 J£_ federal state county local depository for survey records Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission city, town Indianapolis state Indiana (continued) 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original site good ruins altered moved date N/A J£_fair unex posed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Lockefield Gardens is located on a superb!ock bounded by Indiana Avenue on the north, Blake Street on the east, North Street on the south and Locke Street on the west.