Indiana Avenue Paul Mullins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 6 Number 1 2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy L. Draeger-Williams, Archaeologist Wade T. Tharp, Archaeologist Rachel A. Sharkey, Records Check Coordinator Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D. Amy L. Johnson Cathy A. Carson Editorial Assistance: Cathy Draeger-Williams Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service is gratefully acknow- ledged for their support of Indiana archaeological research as well as this volume. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. This publication has been funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service‘s Historic Preservation Fund administered by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. In addition, the projects discussed in several of the articles received federal financial assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund Program for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the State of Indiana. -

Indypl Shared System, 2018-19

INDYPL SHARED SYSTEM, 2018-19 Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory School Cardinal Ritter High School 2801 West 86th Indianapolis, IN 46268 3360 West 30th St Indianapolis, IN 46222 (317) 524-7050 317-924-4333 http://brebeuflibrary.blogspot.com/ www.cardinalritter.org Site code: BRE Site code: CRI School type: High school School type: High school Karcz, Charity, School library manager Jessen, Elizabeth, School library manager [email protected] [email protected] Russell, Suzanne, Assistant Library Manager Cathedral High School [email protected] 5225 E. 56th St. Indianapolis, IN 46226 317-542-1481 x 389 Building Blocks Academy http://www.cathedral-irish.org/page.cfm?p=26 3515 N. Washington Blvd, Indianapolis, IN 46205 (317) 921-1806 Site code: CHS https://www.buildingblocksacademy-bba.com/ School type: High school Site code: BBA Cataldo, Alannah, Library assistant School type: Elementary [email protected] Burksbell, Wanda, School library manager Herron, Jennifer, School library manager [email protected] [email protected] Jewish Community Library Central Catholic School Jewish Federation of Greater Indianapolis 1155 Cameron Street Indianapolis, IN 46203 6705 Hoover Road, Indianapolis, IN 46260 (317) 783-7759 317-726-5450 Site code: CCS https://www.jewishindianapolis.org/ School type: Elementary Site code: BJE Mendez, Theresa, School library manager Library type: Special [email protected] Marcia Goldstein, Library Manager Christel House Academy South [email protected] 2717 South East Street Indianapolis, IN -

Black History News & Notes

BLACK HISTORY NEWS & NOTES INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY February, 1982 No. 8 ) Black History Now A Year-round Celebration A new awareness of black history was brought forth in 1926 when Carter Woodson in augurated Negro History Week. Since that time the annual celebration of Afro-American heritage has grown to encompass the entire month of February. Now, with impetus from concerned individuals statewide, Indiana residents are beginning to witness what hope fully will become a year-round celebration of black history. During the weeks and months immediately ahead a number of black history events have been scheduled. The following is a description of some of the activities that will highlight the next three months. Gaines to Speak Feb. 2 8 An Afro-American history lecture by writer Ernest J. Gaines on February 28 is T H E A T E R Indiana Av«. being sponsored by the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library (I-MCPL). Gaines BIG MIDNITE RAMBLE is the author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and several other works ON OUR STAGE pertaining to the black experience. The lecture will be held at 2:00 P.M. at St. Saturday Night Peter Claver Center, 3110 Sutherland Ave OF THIS WEEK nue. Following the event, which is free DECEMBER 15 1UW l\ M. and open to the public, Gaines will hold Harriet Calloway an autographing session. Additional Black QUEEN OF HI DE HO History Month programs and displays are IN offered by I-MCPL. For further informa tion call (317) 269-1700. DIXIE ON PARADE W ITH George Dewey Washington “Generations” Set for March Danny and Eddy FOUH PENNIES COOK and BROWN A national conference will be held JENNY DANCER FLORENCE EDMONDSON in Indianapolis March 25-27 focusing on SHORTY BURCH FRANK “Red” PERKINS American family life. -

Remembering Kenneth Nebenzahl 16 September 1927 – 29 January 2020

A Publication of the Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography at the Newberry Library and the Chicago Map Society Number 132 | Spring 2020 Remembering Kenneth Nebenzahl 16 September 1927 – 29 January 2020 Kenneth Nebenzahl, internationally known antiquarian turned his energies to the pursuit of a lifelong interest book and map seller, author, and supporter and bene- in maps, books, and history, and became a dealer in an- factor of the field of the history of cartography, passed tiquarian maps and books. He soon established himself away peacefully at his home in Glencoe, Illinois, on not only as Chicago’s premier map dealers, but also as 29 January 2020, at the age of 92. Mr. Nebenzahl was one of the most renowned dealers in maps and books born and grew up in Far Rockaway, New York, but worldwide. moved to Chicago after marrying Jocelyn (Jossy) Spitz Operating as “Kenneth Nebenzahl, Inc.” with in 1953, settling in the North Shore suburb of Glencoe. Jossy as partner, Mr. Nebenzahl was renowned for the Ken joined the Marines at age 17, serving in the last erudition and breadth of his catalogs, which he pro- year of World War II. He first developed his skills as a duced until 1989. Ken also was very active and suc- salesman and businessman while working for the Paul cessful as agent for libraries, assisting them in the ac- Masson winery, but shortly after moving to Chicago he quisition of large collections. The Newberry Library PB was a major beneficiary of these services. From 1958 of the Holy Land (1986), Atlas of Columbus and the to 1967 he assisted the library in the prolonged nego- Great Discoveries (1990), and Mapping the Silk Road tiations to acquire the renowned Americana collection and beyond (2004), some of them translated into of Frank Deering. -

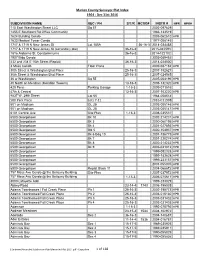

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave -

John Hart Ely's "Invitation"

Indiana Law Journal Volume 54 Issue 2 Article 5 Winter 1979 Government by Judiciary: John Hart Ely's "Invitation" Raoul Berger Member, Illinois and District of Columbia bars Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Courts Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Berger, Raoul (1979) "Government by Judiciary: John Hart Ely's "Invitation"," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 54 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol54/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Government by Judiciary: John Hart Ely's "Invitation" RAOUL BERGER* Professor John Hart Ely's Constitutional Interpretivism: Its Allure and Impossibility' solves the problem of government by judiciary quite simply: the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment issued an "open and across-the-board invitation to import into the constitutional decision pro- cess considerations that will not be found in the amendment nor even, at least in any obvious sense, elsewhere in the Constitution. ' 2 This but rephrases the current view, framed to rationalize the Warren Court's revolution, that the "general" terms of the amendment were left open- 3 ended to leave room for such discretion. By impossible "interpretivism" Ely refers to the belief that constitu- tional decisions should be derived from values "very clearly implicit in the written Constitution"; he labels as "non-interpretivism" the view that courts must range beyond those values to "norms that cannot be discovered within the four corners of the document."'4 But unlike most of his confreres, Ely insists that a constitutional decision must be rooted in the Constitution,5 though he does not explain how extra-constitutional factors can be so rooted. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Fletcher "Flash" Wiley

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Fletcher "Flash" Wiley Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Wiley, Fletcher Houston, 1942- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Fletcher "Flash" Wiley, Dates: October 15, 2004 and September 11, 2019 Bulk Dates: 2004 and 2019 Physical 14 Betacame SP videocasettes uncompressed MOV digital video Description: files (6:53:58). Abstract: Lawyer Fletcher "Flash" Wiley (1942 - ) , CEO of the Centaurus Group, LLC and of counsel to the law firm of Morgan Lewis & Bockius, LLP, co-founded the law firm of Budd, Reilly and Wiley, and was vice president and general counsel of PRWT Services, Inc. Wiley was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 15, 2004 and September 11, 2019, in Boston, Massachusetts and Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2004_206 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Lawyer and civic leader Fletcher “Flash” Wiley was born on November 29, 1942 in Chicago, Illinois. Four years after his birth, Wiley’s family moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, where he was raised. In 1953, Wiley was selected as a charter member of the “Gifted Child Program” by the Indianapolis Public Schools, in which he was the only African American in his class. Upon graduation from Shortridge High School in 1960, Wiley was recruited by the United States Air Force Academy and became the first African American from the State of Indiana Force Academy and became the first African American from the State of Indiana appointed to a military academy, as well as the school’s first African American football player. -

William H. Hudnut III Collection L523

William H. Hudnut III collection L523 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 17, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books and Manuscripts 140 North Senate Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana, 46204 317-232-3671 William H. Hudnut III collection L523 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Series 1: Correspondence and general papers, 1969-1974..................................................................... 8 Series 2: Watergate papers, 1971-1974...............................................................................................103 -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 (7-B1) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Lockefield Garden Apartments and/or common Lockefield Gardens 2. Location street & number 900 Indiana Aventrer not for publication city, town Indi anapol i s vicinity of state Indiana code 0] 8 county Marion codeQ97 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A AY no military JL_ other: Vacant 4. Owner of Property name Indianapolis Housing Authority street & number 410 N. Meridian Street city, town Indianapolis vicinity of state Indiana 46204 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Center Township Assessor street & number 1321 City-County Building city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 46204 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Preservation Work Paper, Regional title Center Plan. Indianapolis__________has this property been determined eligible? _X_yes no date January, 1981 J£_ federal state county local depository for survey records Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission city, town Indianapolis state Indiana (continued) 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original site good ruins altered moved date N/A J£_fair unex posed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Lockefield Gardens is located on a superb!ock bounded by Indiana Avenue on the north, Blake Street on the east, North Street on the south and Locke Street on the west. -

Kentucky Principal Preparation Programs: a Contemporary History Thomas Henry Hart Eastern Kentucky University

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2015 Kentucky Principal Preparation Programs: A Contemporary History Thomas Henry Hart Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Hart, Thomas Henry, "Kentucky Principal Preparation Programs: A Contemporary History" (2015). Online Theses and Dissertations. 268. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/268 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY PRINCIPAL PREPARATION PROGRAMS: A CONTEMPORARY HISTORY By Thomas Henry Hart Bachelor of Science University of Kentucky Lexington, Kentucky 1974 Master of Science Troy State University Troy, Alabama 1979 Master of Engineering Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1984 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2015 Copyright © Thomas Henry Hart, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to first thank my committee co-chair, Dr. James R. Bliss, for his steadfast encouragement, advice and support in pursuing my passion for better understanding principal preparation programs and helping me narrow my focus to a manageable population: principal preparation programs in Kentucky. I would like to also thank the other members of my committee, my committee chair Dr. Paul Erickson, and committee members Dr. -

Shortridge High School

REINVENTING IPS HIGH SCHOOLS Facility Recommendations to Strengthen Student Success in Indianapolis Public Schools June 28, 2017 1 Table of Contents i. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 ii. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 iii. School Profiles ............................................................................................................................................................ 10 a. Arlington High School ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 b. Arsenal Technical High School ............................................................................................................................................... 11 c. Broad Ripple High School ......................................................................................................................................................... 12 d. Crispus Attucks High School ................................................................................................................................................... 13 e. George Washington High School ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Saints and St Louis 18311857 an Oasis of Tolerance and Security

the saints and st louis 183118571831 1857 an oasis of tolerance and security stanley B kimball although surrounded by apostates we feel per- fectly safe in the midst of an enlightened people who alike know how to appreciate political liberty and religious free- dom conference resolution 10 feb 1845 this city has beananbeenanbeen an asylum for our people from fifteen to twenty years there is probably no city in the world where the latter day saints are more respected and where they may sooner obtain an outfit for utah the hand of the lord is in these things st louis luminaryLummary 3 feb 1855 during most of the nineteenth century st louis was the hub of trade and culture for the great western waterway system of the upper and lower mississippi ohio missouri and illinois rivers founded by the french in 1764 st louis was by the time the cormonsmormons first visited it a sixty seven year old settlement a nine year old city a young giant des- tined to become the fourth city of our country by the end of the century throughout the missouri and illinois periods of the church up to the coming of the railroad to utah in 1869 and beyond st louis was the most important non mormon city in church history it became not only an oasis of tolerance and security for the Morcormonsmormonsmons but a self sufficient city never fully identified or connected with rural missouri or with nearbynear by illinois dr kimball professor of history at southern illinois university at edwards ville works in two fields of historical research east european and mormon he has