The Battle of Bogotá

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marisol Cano Busquets

Violencia contra los periodistas Configuración del fenómeno, metodologías y mecanismos de intervención de organizaciones internacionales de defensa de la libertad de expresión Marisol Cano Busquets TESIS DOCTORAL UPF / 2016 DIRECTORA DE LA TESIS Dra. Núria Almiron Roig DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICACIÓN A Juan Pablo Ferro Casas, con quien estamos cosidos a una misma estrella. A Alfonso Cano Isaza y María Antonieta Busquets Nel-lo, un árbol bien plantado y suelto frente al cielo. Agradecimientos A la doctora Núria Almiron, directora de esta tesis doctoral, por su acom- pañamiento con el consejo apropiado en el momento justo, la orientación oportuna y la claridad para despejar los caminos y encontrar los enfoques y las perspectivas. Además, por su manera de ver la vida, su acogida sin- cera y afectuosa y su apoyo en los momentos difíciles. A Carlos Eduardo Cortés, amigo entrañable y compañero de aventuras intelectuales en el campo de la comunicación desde nuestros primeros años en las aulas universitarias. Sus aportes en la lectura de borradores y en la interlocución inteligente sobre mis propuestas de enfoque para este trabajo siempre contribuyeron a darle consistencia. A Camilo Tamayo, interlocutor valioso, por la riqueza de los diálogos que sostuvimos, ya que fueron pautas para dar solidez al diseño y la estrategia de análisis de la información. A Frank La Rue, exrelator de libertad de expresión de Naciones Unidas, y a Catalina Botero, exrelatora de libertad de expresión de la Organización de Estados Americanos, por las largas y fructíferas conversaciones que tuvimos sobre la situación de los periodistas en el mundo. A los integrantes de las organizaciones de libertad de expresión estudia- das en este trabajo, por haber aceptado compartir conmigo su experien- cia y sus conocimientos en las entrevistas realizadas. -

The Farc-Ep and Revolutionary Social Change

Emancipatory Politics: A Critique Open Anthropology Cooperative Press, 2015 edited by Stephan Feuchtwang and Alpa Shah ISBN-13:978-1518885501 / ISBN-10:1518885500 Part 2 Armed movements in Latin America and the Philippines Chapter 4 The FARC-EP and Consequential Marxism in Colombia James J. Brittain Abstract The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) has maintained its base among small-holders including coca farmers and expanded its struggle through a local interpretation of Marxism and Leninism. This chapter reviews current accounts of its history and contemporary presence. The author then provides his own analysis of their strategy, namely that they have successfully pursued a gradual expansion of a separate power base and economy from that of the state and its capitalist economy, a situation that Lenin described as ‘dual power’, or, as Gramsci elaborated, a challenge to the hegemony of the ruling bloc. His visits and interviews and two recent documentary films in the FARC-EP areas show that the economy under FARC leadership, while taxing and controlling the processing and selling of coca, is still one of private small-holders. Many farmers grow coca as their main crop but all to some extent diversify into subsistence crops. This is a successful preparation for eventual state power of a completely different kind under which the economy will be socialised. For a half century the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias Colombianas-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP) have played a key role in organising, sustaining, and leading revolutionary activity within the Latin American country of Colombia. -

Ending Colombia's FARC Conflict: Dealing the Right Card

ENDING COLOMBIA’S FARC CONFLICT: DEALING THE RIGHT CARD Latin America Report N°30 – 26 March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FARC STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES................................................................... 2 A. ADAPTIVE CAPACITY ...................................................................................................................4 B. AN ORGANISATION UNDER STRESS ..............................................................................................5 1. Strategy and tactics ......................................................................................................................5 2. Combatant strength and firepower...............................................................................................7 3. Politics, recruitment, indoctrination.............................................................................................8 4. Withdrawal and survival ..............................................................................................................9 5. Urban warfare ............................................................................................................................11 6. War economy .............................................................................................................................12 -

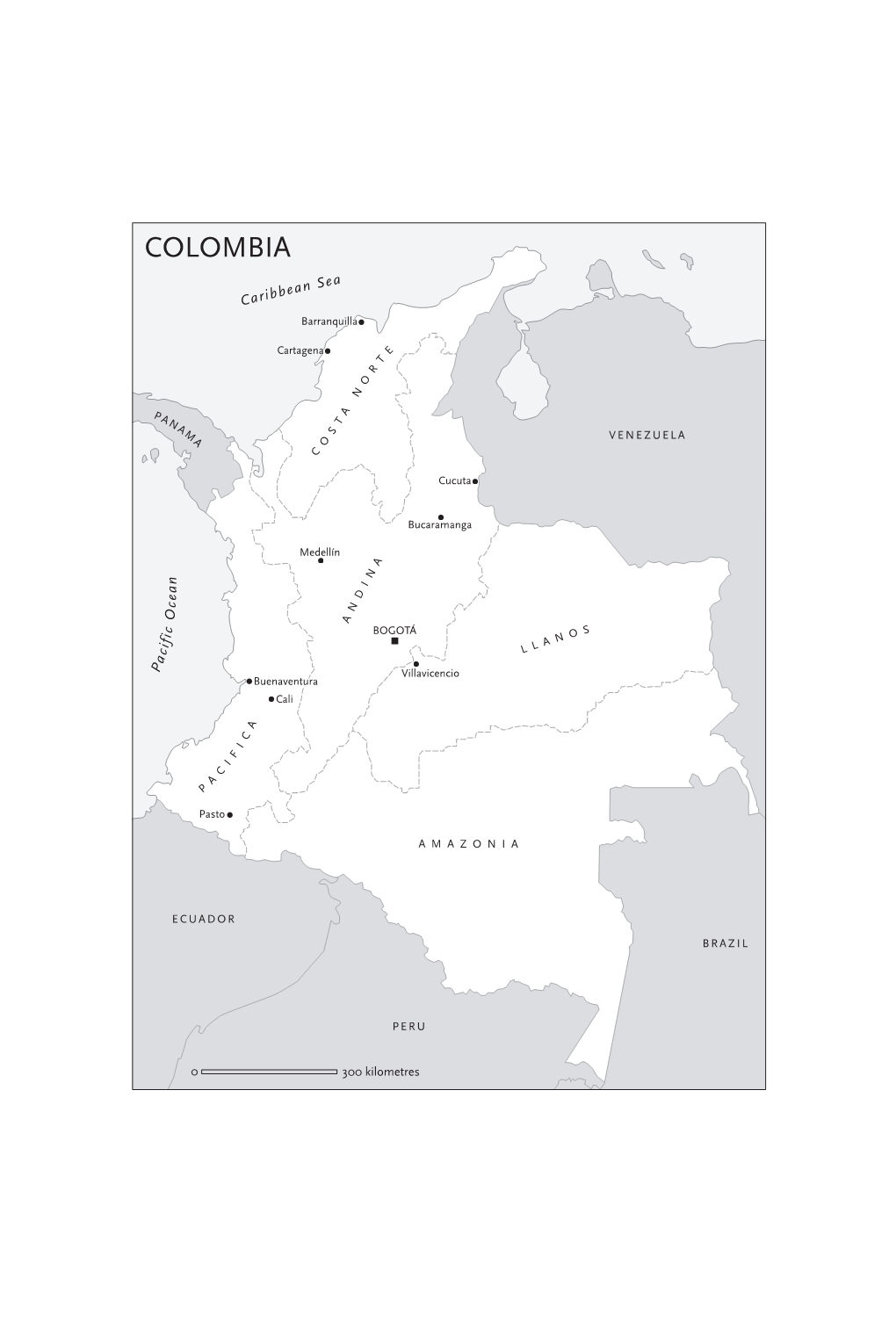

Colombia Country Fact Sheet

National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Page 1 of 4 Home > Research > National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Country Fact Sheet COLOMBIA April 2007 Disclaimer 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Official name Republic of Colombia. Geography Colombia is located at the northern point of South America and shares borders with Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil and Venezuela. Colombia has a total of 3,208 km of coastline on the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. The total area is 1,038,700 km2. The coast has a tropical climate, the interior plateaux are temperate and some Andean areas have snow year-round. Population and density Population: 43,593,035 (July 2006 estimate). Density: 39.7 persons per km2. Principal cities and populations (2005 estimate) Bogota (political capital) 8,350,000; Medellin 3,450,000; Cali 2,700,000; Barranquilla 1,925,000; Cartagena 1,075,000. Languages Spanish (official). Religions Catholic 90%. Ethnic groups Mestizo 58%, white 20%, mulatto 14%, black 4%, mixed black-Amerindian 3%, Amerindian 1%. Approximately 75 % of Colombians are of mixed-blood. Demographics http://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca:8080/Publications/PubIP_DI.aspx?id=209&pcid=359 2/23/2011 National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Page 2 of 4 Population growth rate: 1.46% (2006 estimate). Infant mortality rate: 20.35 deaths/1,000 live births. Life expectancy at birth: 72.6 (2004). Fertility rate: 2.54 children born/woman (2006 estimate). Literacy: 92.8% of people aged 15 and older can read and write (2004). Currency Colombian Peso (COP). -

Ending Colombia's FARC Conflict

ENDING COLOMBIA’S FARC CONFLICT: DEALING THE RIGHT CARD Latin America Report N°30 – 26 March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FARC STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES................................................................... 2 A. ADAPTIVE CAPACITY ...................................................................................................................4 B. AN ORGANISATION UNDER STRESS ..............................................................................................5 1. Strategy and tactics ......................................................................................................................5 2. Combatant strength and firepower...............................................................................................7 3. Politics, recruitment, indoctrination.............................................................................................8 4. Withdrawal and survival ..............................................................................................................9 5. Urban warfare ............................................................................................................................11 6. War economy .............................................................................................................................12 -

Political Finance and the Equal Participation of Women in Colombia: a Situation Analysis

Political finance and the equal participation of women in Colombia: a situation analysis The impact of economic resources on the political participation of women has become a prominent issue in the field of comparative political finance. In recent Kevin Casas-Zamora and Elin Falguera years, there has been a growing recognition that politics dominated by money is, more often than not, politics dominated by men. It is not surprising that the issue has moved to the forefront of debates on gender and political finance. This report assesses the extent to which political finance is a significant obstacle to women running for political office. It focuses on the experience of Colombia, a country that, like many other Latin American countries, continues to struggle with the legacies of pervasive social, economic and political inequality that disproportionately affect women. It explores the role of political finance in hindering women’s access to political power and its relative weight with respect to other obstacles to women’s political participation. It also suggests a number of institutional changes that might ameliorate some of the problems identified, while being fully cognizant of the limits to institutional change recasting deep-rooted gender imbalances. International IDEA NIMD Strömsborg Passage 31 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2511 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 (0) 8 698 37 00 T +31 (0)70 311 54 64 F +46 (0) 8 20 24 22 F +31 (0)70 311 54 65 [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.nimd.org About the organizations About the authors International IDEA Kevin Casas-Zamora is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Peter D. -

The Political Culture of Democracy in Colombia, 2011 Democratic Attitudes PostUribe

The Political Culture of Democracy in Colombia, 2011 Democratic Attitudes PostUribe Juan Carlos Rodríguez Raga, Ph.D. Universidad de los Andes Mitchell A. Seligson, Ph.D. Vanderbilt University ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… … This study was made possible thanks to support provided by the program for Democracy and Human Rights of the United States Agency for International Development. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of the United States Agency for International Development. Bogotá, November 2011 Table of contents 3 Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF TABLES ..............................................................................................................................................................11 PROLOGUE: BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY ....................................................................................................................13 Acknowledgements.....................................................................................................................................................................15 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................................17 -

Latin America's Shifting Politics

October 2018, Volume 29, Number 4 $14.00 Latin America’s Shifting Politics Steven Levitsky Forrest Colburn and Arturo Cruz S. Alberto Vergara Carlos de la Torre Jean-Paul Faguet Laura Gamboa Kenneth Greene and Mariano Sánchez-Talanquer Democracy’s Near Misses Tom Ginsburg and Aziz Huq Liberal Democracy’s Crisis of Confidence Richard Wike and Janell Fetterolf Alexander Libman & Anastassia Obydenkova on Authoritarian Regionalism Sophie Lemi`ere on Malaysia’s Elections Christopher Carothers on Competitive Authoritarianism Tarek Masoud on Tunisian Exceptionalism Why National Identity Matters Francis Fukuyama Latin America’s Shifting Politics THE PEACE PROCESS AND COLOMBIA’S ELECTIONS Laura Gamboa Laura Gamboa is assistant professor of political science at Utah State University. She is currently working on a book that examines opposition strategies against democratically elected presidents who try to under- mine checks and balances and stay in office, effectively eroding democ- racy. Her work has been published in Political Research Quarterly and Comparative Politics. As his two terms in the presidency neared their end in 2018, Juan Manuel Santos might have expected that he would be enjoying high standing among his fellow Colombians. Having won the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize for his role as leader of a peace deal with the long-running leftist insurgency known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Co- lombia (FARC), Santos could fairly claim to be leaving his country of fifty-million people a better democracy than it had been when he first took office in 2010. The peace agreement is Colombia’s most important achievement in recent decades. Signed in November 2016, the accord ended an armed conflict that had gone on for more than five decades. -

Colombian Conservative Party, Colombian Liberal Party, Social National Unity Party

Political Highlights Government type: Presidential Republic Head of state: Ivan Duque Marquez Elections/appointments: The president is directly elected by absolute majority vote for a 4-year term Next legislative and presidential elections are due in March 2022 and May 2022 respectively Legal system: Civil law Legislative branch: Bicameral congress (108-seat Senate and 172-seat Chamber of Representatives) Major political parties: Democratic Center Party, Radical Change, Colombian Conservative Party, Colombian Liberal Party, Social National Unity Party Economic Trend Economic Indicators 2018 2019 2020* 2021^ 2022^ Nominal GDP (USD bn) 333.5 323.6 264.9 280.4 296.2 Real GDP growth (%) 2.5 3.3 -8.2 4 3.6 GDP per capita (USD) 6,692 6,423 5,207 5,457 5,713 Inflation (%) 3.2 3.5 2.4 2.1 2.5 Current account balance (% of GDP) -3.9 -4.2 -4 -3.9 -3.8 General government debt (% of GDP) 53.7 52.3 68.2 68.1 67.3 *Estimate ^Forecast Hong Kong Total Exports to Colombia Hong Kong Total Exports to Colombia (HK$ billion) (World) (Colombia) Year Colombia World 4,500 7.0 2011 2.5 3,337 4,000 2012 2.6 3,434 6.0 2013 3.4 3,560 3,500 2014 5.3 3,673 5.0 2015 5.4 3,605 3,000 2016 World 3.9 3,588 4.0 2017 3.7 3,876 2,500 2018 Colombia 6.1 4,158 2,000 2019 5.3 3,989 (HK$ billion) 3.0 2020 3.5 3,928 1,500 2.0 1,000 1.0 500 0 0.0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Hong Kong Exports to Colombia by Product (% share) Hong Kong Exports to Colombia by Product (2020) Electrical machinery, Product 2020 apparatus and Telecommunications and sound recording -

The Hope for Peace in Colombia Pedro Valenzuela

armed conflict and peace processes 47 II. Out of the darkness? The hope for peace in Colombia pedro valenzuela On 24 November 2016, after more than five decades of armed conflict, several failed peace processes and four years of negotiations, the Colombian Gov- ernment and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC– EP) signed the Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace (the Accord).1 The Accord ended a conflict that has cost the lives of around 220 000 people, led to the disappearance of 60 000 more, forcibly recruited 6000 minors and left 27 000 victims of kidnapping as well as more than 6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees.2 This section discusses the circumstances that made the Accord possible, the development of the process and the challenges that lie ahead. Factors leading to negotiations The origins of FARC can be traced to the peasant self-defence units created by the Communist Party during the inter-party conflicts of the 1940s and 1950s, known to Colombians simply as ‘The Violence’. After its formal cre- ation in 1966 and throughout the 1970s, when the armed conflict was fairly marginal, FARC was closely allied with the Communist Party of Colombia. In the 1980s, however, it distanced itself from the Communist Party and promoted clandestine political structures, while attempting to expand into every province of the country, gain power at the local level, bring the war closer to the -

The Formal Determinants of Informal Settlements in Bogota, Colombia

The Formal Determinants of Informal Settlements in Bogota, Colombia by Andres Guillermo Blanco This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Warner,Mildred E (Chairperson) Nicholson,Charles Frederick (Minor Member) Roldan,Mary Jean (Minor Member) THE FORMAL DETERMINANTS OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN BOGOTA, COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Andres Guillermo Blanco August 2010 © 2010 Andres Guillermo Blanco THE FORMAL DETERMINANTS OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN BOGOTA, COLOMBIA Andres Guillermo Blanco, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 The central question in this dissertation is why formal mechanisms of housing production and land allocation have been unable to absorb the growing demand in the cities of the developing world. My general methodological approach is to analyze the historical process of urbanization of Bogotá, Colombia a city known by the prevalence of informality and its rich experience in the implementation of different land and housing policies. My hypothesis is that informal settlements are structural to the formal process of production of the built environment because, within a context of inequality and natural property rights, this process tends to under-provide land with urban services. The dissertation is structured as three interrelated papers. In the first paper, I study the relationship between an institutional context dominated by the concept of property as a natural right and the pattern of under-provision of urban services arguing that informality is engendered in the same formal process of production and allocation of the built environment because the concept of property as a natural right produces a dynamic of privatization of benefits of city growth and socialization of its costs that results in under-provision of urban services. -

“YOU'll LEARN NOT to CRY” Child Combatants in Colombia

“YOU’LL LEARN NOT TO CRY” Child Combatants in Colombia HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH New York • Washington • London • Brussels Copyright © September 2003 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 1564322882 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003109212 Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, DC 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with “subscribe hrw-news” in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all.