S of Real-Time Computing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Paper We Present an Early User Evaluation of a Advances in Sketch-Based Modeling Are Set to Simplify Many Sketch-Based 3D Modeling Tool We Have Been Developing [7,8]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9999/paper-we-present-an-early-user-evaluation-of-a-advances-in-sketch-based-modeling-are-set-to-simplify-many-sketch-based-3d-modeling-tool-we-have-been-developing-7-8-209999.webp)

Paper We Present an Early User Evaluation of a Advances in Sketch-Based Modeling Are Set to Simplify Many Sketch-Based 3D Modeling Tool We Have Been Developing [7,8]

ARTICLE IN PRESS Computers & Graphics 31 (2007) 580–597 www.elsevier.com/locate/cag Calligraphic Interfaces An evaluation of user experience with a sketch-based 3D modeling system Levent Burak KaraÃ, Kenji Shimada, Sarah D. Marmalefsky Mechanical Engineering Department, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA Abstract With the availability of pen-enabled digital hardware, sketch-based 3D modeling is becoming an increasingly attractive alternative to traditional methods in many design environments. To date, a variety of methodologies and implemented systems have been proposed that all seek to make sketching the primary interaction method for 3D geometric modeling. While many of these methods are promising, a general lack of end user evaluations makes it difficult to assess and improve upon these methods. Based on our ongoing work, we present the usage and a user evaluation of a sketch-based 3D modeling tool we have been developing for industrial styling design. The study investigates the usability of our techniques in the hands of non-experts by gauging (1) the speed with which users can comprehend and adopt to constituent modeling steps, and (2) how effectively users can utilize the newly learned skills to design 3D models. Our observations and users’ feedback indicate that overall users could learn the investigated techniques relatively easily and put them in use immediately. However, users pointed out several usability and technical issues such as difficulty in mode selection and lack of sophisticated surface modeling tools as some of the key limitations of the current system. We believe the lessons learned from this study can be used in the development of more powerful and satisfying sketch-based modeling tools in the future. -

HCI Remixed : Essays on Works That Have Influenced the HCI

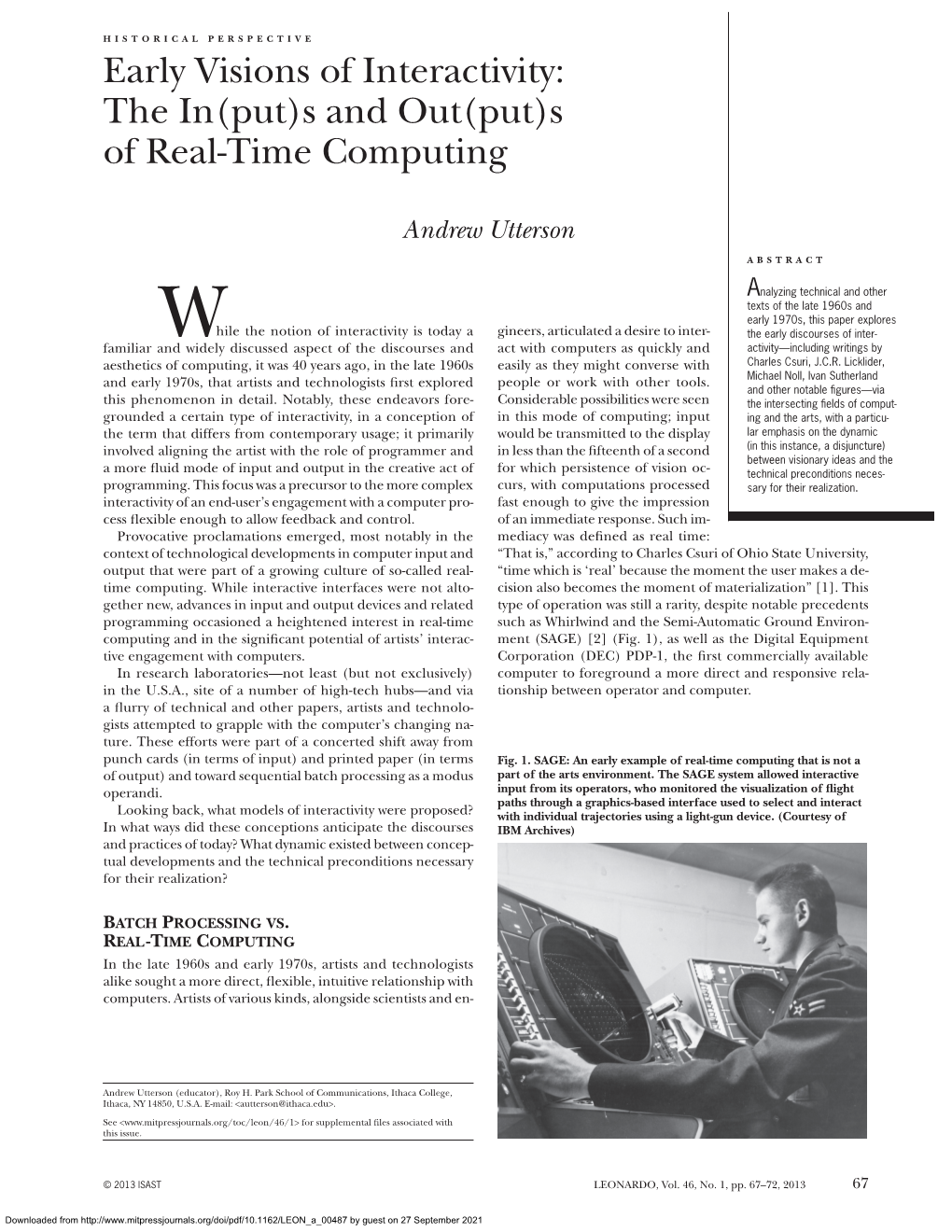

4 Drawing on SketchPad: Refl ections on Computer Science and HCI Joseph A. Konstan University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S.A. I. Sutherland, 1963: “Sketchpad: A Man–Machine Graphical Communication System” Sutherland’s SketchPad system, paper, and dissertation provide, for me, the answer to the oft-asked question: “why should HCI belong in a computer science program?” I fi rst came across the paper “SketchPad: A Man–Machine Graphical Communica- tion System” from the 1963 AFIPS conference nearly thirty years after it had been published (Sutherland 1963). I was nearing completion of my own dissertation in which I was exploring a variety of techniques for constructing user interface toolkits. At the time, the paper seemed little more than a handy reference in which I could trace the lineage of constraint programming in user interfaces—from Sketchpad, through Borning’s ThingLab (Borning 1981), to my own work, with various hops and detours along the way. I guess I was young and in a hurry. It was only a few years later when I started to teach this material that I realized how much of today’s computing traces its roots to Sutherland’s work. What was this tremendous paper about? A drawing program. Not just any drawing program, but one that took full advantage of computing, a million-pixel display (albeit with a slow pixel-by-pixel refresh), a light pen, and various buttons and dials to empower users to draw and repeat patterns, to integrate constraints with draw- ings so as to better understand mechanical systems, and to draw circuit diagrams as input to simulators. -

A New Era for Mechanical CAD Time to Move Forward from Decades-Old Design JESSIE FRAZELLE

TEXT COMMIT TO 1 OF 12 memory ONLY A New Era for Mechanical CAD Time to move forward from decades-old design JESSIE FRAZELLE omputer-aided design (CAD) has been around since the 1950s. The first graphical CAD program, called Sketchpad, came out of MIT [designworldonline. com]. Since then, CAD has become essential to designing and manufacturing hardware Cproducts. Today, there are multiple types of CAD. This column focuses on mechanical CAD, used for mechanical engineering. Digging into the history of computer graphics reveals some interesting connections between the most ambitious and notorious engineers. Ivan Sutherland, who won the Turing Award for Sketchpad in 1988, had Edwin Catmull as a student. Catmull and Pat Hanrahan won the Turing award for their contributions to computer graphics in 2019. This included their work at Pixar building RenderMan [pixar. com], which was licensed to other filmmakers. This led to innovations in hardware, software, and GPUs. Without these innovators, there would be no mechanical CAD, nor would animated films be as sophisticated as they are today. There wouldn’t even be GPUs. Modeling geometries has evolved greatly over time. Solids were first modeled as wireframes by representing the object by its edges, line curves, and vertices. This evolved into surface representation using faces, surfaces, edges, and vertices. Surface representation is valuable in robot path planning as well. Wireframe and surface acmqueue |march-april 2021 5 COMMIT TO 2 OF 12 memory I representation contains only geometrical data. Today, modeling includes topological information to describe how the object is bounded and connected, and to describe its neighborhood. -

Syllabus: Art 4366-Interactive Design

Art 4348 - Interactive Design, 2013 Fall p. 1 SYLLABUS: ART 4366-INTERACTIVE DESIGN INSTRUCTOR Seiji Ikeda Assistant Professor Office: Fine Arts Building 369-C Hours: Tuesdays, 10-11am [email protected] CLASS INFORMATION Art 4348 - Interactive Design, Section 1 Fine Arts Building 368-A, Monday and Wednesday, 11-1:50pm CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION Comprehensive analysis of interactive concepts and the role of new media in relationship to the field of visual communications. The student will explore and construct innovative uses of interaction using coding and contemporary applications. May be repeated for credit. Prerequisite: ART 3354: SIGN AND SYMBOL, or permission of the advisor. COURSE OBJECTIVES The course will explore interactive media and trends in web design and development. The basic course structure is a combination of seminars (made up of lecture, readings, discussion, research of topics) and practical digital projects. Comprehensive learning of how the theoretical and sociological impact of today’s media & design has on the culture and the individual will be emphasized. The class will research and implement effective ideas solving visual problems in navigation, interface design, and layout design through the use of type, graphic elements, texture, motion and animation. Main projects will revolve around creating Motion-based websites. DESCRIPTION OF INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS The structure of the class includes lectures, demonstrations, group discussion, individual and group critiques and in/outside class studio activities. Projects will be assigned and will be due on scheduled dates. Each project will include an introduction to the specifics of what is expected and what concepts we are covering. At the completion of assigned projects a critique/class review will take place. -

Facilitating the Implementation of Computer-Aided Design Into the Engineering Graphics and Design Classroom

Facilitating the implementation of Computer-Aided Design into the Engineering Graphics and Design classroom by Ciana Rust Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER EDUCATIONIS in the Faculty of Education at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF L VAN RYNEVELD AUGUST 2017 Declaration I declare that the dissertation, which I hereby submit for the degree Magister Educationis at the University of Pretoria, is my own work and has not previously been submitted by me for a degree at this or any other tertiary institution. ............................................................. Ciana Rust 31 August 2017 i Ethical Clearance Certificate ii iii iv Dedication I dedicate this research to my family, friends, colleagues and learners whom I have taught throughout my educational career. Without my mother, father and brother, I would not be the person who I am today. They have guided me to choose education as a career path, which led me to this point in my life. All my love goes out to you. To my glorious Father who gave me the strength, dedication and patience to persevere throughout this process of discovery, I thank Thee. v Acknowledgements To have achieved this milestone in my life, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following people: My Heavenly Father, who provided me with the strength, knowledge and perseverance to complete this study; Prof Linda van Ryneveld, research supervisor, for her invaluable advice, guidance and inspiring motivation during difficult times and throughout the research; My editor, Leandri le Roux, without whom this would not have been possible; Last but not least, my beautiful family and amazing friends. -

21 Miscellaneous Companies

Chapter 21 Miscellaneous Companies Space restrictions simply do not permit me to go into the depth of detail I would like on every company that participated in the early days of the CAD industry nor cover numerous in-house systems developed at major automobile and aerospace companies. Readers will have to be satisfied with the brief descriptions included in this chapter and even then, I have only been able to cover what I consider to be the companies that had the biggest impact. There are hundreds if not thousands of companies that at one time marketed engineering design software. Some of the companies described in this chapter offered just software while other provided both hardware and software. While many have changed names, I have decided to list them alphabetically based upon the name they are best been known by along with earlier and subsequent name changes. Adra Systems (Matrix One) Adra Systems was founded in Lowell, Massachusetts in July 1983 by William Mason, who had been at Applicon from 1973 to 1983, most recently as vice president of operations, James Stenzel, who had been vice president of engineering at Hastech, Inc., and Peter Stoupas, who had earlier been a regional sales manager at Adage and had also worked for Applicon. Mason became the president and CEO, Stenzel the vice president of product development and Stoupas the vice president of marketing. Between 1983 and 1986, the company raised $11.6 million of venture funding from a number of firms including American Research & Development, the company that also provided the initial funding for Digital Equipment Corporation. -

Ii Topic Outline Idi 1

AVICENNE WBT: DESIGN & IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES – II TOPIC OUTLINE IDI 1 - Interactive Design Principles 1.1. Interactive Vocabulary 1.1.1 Hypertext 1.1.2 Hypermedia 1.1.3 Link 1.1.4 Nodes 1.1.5 Branching 1.1.6 Node Map 1.1.7 Navigation 1.2 Multimedia as a System 1.3 Component of the System 1.3.1 Component Drivers 1.3.1.1 Target User 1.3.1.2 Venue 1.3.1.3 Purpose 1.3.1.4. Subjects 1.3.1.4 Genres 1.3.2 Multimedia Components 1.4. The User Interface 1.4.1 The Metaphor 1.4.2. Principles of Good Interface IDI1 - CONCEPT MAP Objectives of the Lesson At the end of this lecture learners will be able to 1. Analyze an interactive system based on interactive vocabulary 2. Develop an interactive system including links, hypertext or hypermedia, nodes, node map, and etc. 3. Investigate a multimedia system with respect to drivers and components 4. Analyze users interfaces for their effectiveness and efficiency 5. Evaluate and make recommendations for an interface 6. Establish a relationship among concepts multimedia, interactivity, and user interface IDI 1 - Interactive Design Principles 1.1. Interactive Vocabulary 1.1.1 Hypertext A tool placed or embedded into text. However, this text differs from normal texts due to its functionality that allows users to link, go, and jump to other related segment of content. It is fundamental term of interactivity. It can be also stated as the most primitive type of interaction. It is the origin of interactivity civilization. -

Expressing and Reusing Design Intent in 3D Models

CHI 2018 Paper CHI 2018, April 21–26, 2018, Montréal, QC, Canada Greater than the Sum of its PARTs: Expressing and Reusing Design Intent in 3D Models Megan Hofmann,❇ Gabriella Hann,❇ Scott E. Hudson,❇ Jennifer Mankoff† † ❇Human Computer Interaction Institute Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania University of Washington, Seattle, Washington {meganh, ghhann, scott.hudson}@cs.cmu.edu [email protected] ABSTRACT modeling design intent in the hands of non-expert modelers. With the increasing popularity of consumer-grade 3D This supports reuse, experimentation, and sharing. printing, many people are creating, and even more using, PARTs’ basic abstraction, functional geometry, is analogous objects shared on sites such as Thingiverse. However, our to the programming concept of classes [9,22]. Like classes, formative study of 962 Thingiverse models shows a lack of functional geometry encapsulates data and functionality, re-use of models, perhaps due to the advanced skills needed making it easier to validate and mutate data and support for 3D modeling. An end user program perspective on 3D modularity. Functional geometry includes assertions that modeling is needed. Our framework (PARTs) empowers test whether a model is used correctly, and integrators that amateur modelers to graphically specify design intent mutate the larger design context. These abstractions increase through geometry. PARTs includes a GUI, scripting API and model usability and re-usability. exemplar library of assertions which test design expectations and integrators which act on intent to create geometry. The PARTs framework is an extension of the Autodesk PARTs lets modelers integrate advanced, model specific Fusion360 Computer Aided Design (CAD) tool. -

What Is Interaction Design? (1) What Is Interaction Design? (2)

2/1/2010 Basis of Innovation Interaction Design Interaction design Data mining Evolutionary computation Andrew Kusiak The University of Iowa [email protected] Based on D. Saffer, Designing Interaction: Cognitive Innovative Applications and Devices, New Riders, Berkeley, CA, 2010. What is Interaction Design? (1) What is Interaction Design? (2) Not well defined Interdisciplinary roots in: industrial and communication Design is to design a design to produce a design design, human factors, and human-computer interaction John Heskett Interaction Design Much of interaction is not visible E.g., Though Windows and Mac operating systems may have almost the same functionality and look, yet, they feel differently Interaction is about behavior and behavior is difficult to observe and understand 1 2/1/2010 Interaction Design Perspectives Focus of Interaction Design (1) Focusing on users o Designers should advocate users’ expectaions Finding alternatives Technology centered o Designing is not choosing among multiple options, o E.g., use of digital technology o It is about creating options (Genetic programming link) Behaviorist Using ideation and prototyping o Study product behavior and users’ feedback o Many prototypes, e.g., Jeff Hawkins – designer of the original Social interaction design PalmPilot carried around wooden blocks and wrote on them o Facilitating interaction among products and people Collaborating and addressing constraints o Designers deal with teammates, money, materials; and address business goals, deadlines, etc. Focus of Interaction Design (2) History of Interaction Design (1) Creating appropriate solutions Likely begun with Native Americans and other tribes o Appropriate to the situation (Evolutionary computation and evolving landscape link) used smoke and other signals to communicate over Drawing on a wide range of influences long distances E. -

Sketchpad for Windows

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Sudheendra S. Gulur for the degree of Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering presented on October 7, 1994. Title: Sketch Pad for Windows: An Intelligent and Interactive Sketching Software. Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: David. G. Ullman The sketching software developed in this thesis, is aimed to serve as an intelligent design tool for the conceptual design stage of the mechanical design process. This sketching software, Sketch Pad for Windows, closely mimics the traditional paper-and-pencil sketching environment by allowing the user to sketch freely on the computer screen using a mouse. The recognition algorithm built into the application replaces the sketch stroke with the exact CAD entity. Currently, the recognition of two-dimensional design primitives such as lines, circles and arcs has been addressed. Since manufacturing requires that the design concepts be detailed, sketches need to be refined as detailed drawings. This process of carrying design data from the conceptual design stage into the detail designing stage is achieved with the help of a convertor that converts the sketch data into DesignView (a variational CAD software). Currently, only geometrical information is transferred from the sketching software into DesignView. The transparent graphical user interface built into this sketching system challenges the hierarchial and regimental user interface built into current CAD software. Sketch Pad for Windows An Intelligent and Interactive Sketching Software by Sudheendra S. Gulur A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Completed October 7, 1994 Commencement June, 1995 Master of Science thesis of Sudheendra S. -

NX 10 for Engineering Design

NX 10 for Engineering Design By Ming C. Leu Amir Ghazanfari Krishna Kolan Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Contents FOREWORD ............................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 2 1.1 Product Realization Process ..................................................................................................2 1.2 Brief History of CAD/CAM Development ...........................................................................3 1.3 Definition of CAD/CAM/CAE .............................................................................................5 1.3.1 Computer Aided Design – CAD .................................................................................. 5 1.3.2 Computer Aided Manufacturing – CAM ..................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Computer Aided Engineering – CAE ........................................................................... 5 1.4. Scope of This Tutorial ..........................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 2 – GETTING STARTED .................................................................. 8 2.1 Starting an NX 10 Session and Opening Files ......................................................................8 2.1.1 Start an NX 10 Session ................................................................................................. 8 -

Lecture Notes in Computer Science 8345

Lecture Notes in Computer Science 8345 Commenced Publication in 1973 Founding and Former Series Editors: Gerhard Goos, Juris Hartmanis, and Jan van Leeuwen Editorial Board David Hutchison Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK Takeo Kanade Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Josef Kittler University of Surrey, Guildford, UK Jon M. Kleinberg Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA Alfred Kobsa University of California, Irvine, CA, USA Friedemann Mattern ETH Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland John C. Mitchell Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA Moni Naor Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel Oscar Nierstrasz University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland C. Pandu Rangan Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, India Bernhard Steffen TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany Demetri Terzopoulos University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA Doug Tygar University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Gerhard Weikum Max Planck Institute for Informatics, Saarbruecken, Germany For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7409 Achim Ebert • Gerrit C. van der Veer Gitta Domik • Nahum D. Gershon Inga Scheler (Eds.) Building Bridges: HCI, Visualization, and Non-formal Modeling IFIP WG 13.7 Workshops on Human–Computer Interaction and Visualization: 7th HCIV@ECCE 2011 Rostock, Germany, August 23, 2011, and 8th HCIV@INTERACT 2011 Lisbon, Portugal, September 5, 2011 Revised Selected Papers 123 Editors Achim Ebert Gitta Domik Inga Scheler University of Paderborn University of Kaiserslautern Paderborn Kaiserslautern Germany Germany Nahum D. Gershon Gerrit C. van der Veer The MITRE Corporation Open University The Netherlands McLean, VA Heerlen USA The Netherlands ISSN 0302-9743 ISSN 1611-3349 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-642-54893-2 ISBN 978-3-642-54894-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-54894-9 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936290 LNCS Sublibrary: SL3 – Information Systems and Applications, incl.