21 Miscellaneous Companies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programming Parameterised Geometric Objects in a Visual Design Language

PROGRAMMING PARAMETERISED GEOMETRIC OBJECTS IN A VISUAL DESIGN LANGUAGE by Omid Banyasad Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia June 2006 © Copyright by Omid Banyasad, 2006 ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DATE: June 12, 2006 AUTHOR: Omid Banyasad TITLE: PROGRAMMING PARAMETERISED GEOMETRIC OBJECTS IN A VISUAL DESIGN LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: Faculty of Computer Science DEGREE: PhD CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2006 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. Signature of Author The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the thesis (other than the brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledgment in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged. iii Table of Contents List of Tables . .ix List Of Figures . x Abstract . xii List of Abbreviations Used . .xiii Acknowledgments . .xiv CHAPTER 1: Introduction . 1 1.1 Design Tools . 3 1.1.1 Computer-Aided Design . 3 1.1.2 Mechanical Design Versus Digital Design . 5 1.2 Design Languages . 5 1.3 Background . 7 1.4 Research Objectives . 9 1.5 Organisation . 13 CHAPTER 2: Solids in Logic . 14 2.1 Lograph Syntax and Semantics . 15 2.2 LSD . 21 2.3 Relating Lograph to LSD . 27 2.4 Design Synthesis . -

Mitcalc Brochure

MITCalc is a multi-language set of mechanical, industrial and technical calculations for the day-to-day routines. It will reliably, precisely, and most of all quickly guide customer through the design of components, the solution of a technical problem, or a calculation of an engineering point without any significant need for expert knowledge. MITCalc contains both design and check calculations of many common tasks, such as: tooth, belt, and chain gear, beam, shaft, springs, bolt connection, shaft connection and many others. There are also many material, comparison, and decision tables, including a system for the administration of resolved tasks. The calculations support both Imperial and Metric units and are processed according to ANSI, ISO, DIN, BS, CSN and Japanese standards. It is an open system designed in Microsoft Excel which allows not only easy user-defined modifications and user extensions without any programming skills, but also mutual interconnection of the calculations, which is unique in the development of tailor-made complex calculations. The sophisticated interaction with many 2D (AutoCAD, AutoCAD LT, IntelliCAD, Ashlar Graphite, TurboCAD) and 3D (Autodesk Inventor, SolidWorks, Solidedge) CAD systems allows the relevant drawing to be developed or 3D models to be inserted in a few seconds. OEM licensing of selected calculations or the complete product is available as well. MITCalc installation packages are available at www.mitcalc.com and after installation customer have 30 days to freely test the product. CAD support 2D CAD systems: Most of the calculations allow direct output to major 2D CAD systems. Just choose your CAD system in the calculation and select the desired view (a projection type). -

Make Measurement Matter 12 March 2020

94 A-Z OF MEMBERS AND PROFILES 241 MAKE MEASUREMENT MATTER 12 MARCH 2020 The GTMA has teamed up with the successful Engineering Materials Live and FAST LIVE exhibitions, to deliver ‘Make Measurement Matter’ • QUALITY VISITORS • UNIQUE FORMAT • LOW COST Current attendees of the FAST LIVE and Engineering Materials Live events, compliment the Make Measurement Matter content, with visitors involved in production, design engineering, manufacturing, measurement, testing, quality and inspection. ATED WITH CO-LOC ATED WITH CO-LOC ATED WITH CO-LOC H 2020 12 MARC H 2020 0121 392 8994 12 [email protected] www.gtma.co.uk www.gtma.co.uk SUPPLIERSH DIREC 2020T ORY 12 MARC A-Z OF MEMBERS AND PROFILES 95 A-Z of members and members’ profiles INCLUDING: SECTORS AND MARKET SERVED BY INDIVIDUAL COMPANIES Find the right company for the right product and service. For up-to-date information please also see: www.gtma.co.uk 96 A-Z OF MEMBERS AND PROFILES 241 3D LASERTEC LTD Mansfield i-centre T 01623 600 627 Oakham Business Park W www.3dlasertec.co.uk Hamilton Way, Mansfield Nottinghamshire NG18 5BR Managing Director & Sales Contact: Wayne Kilford Sales Contact: Patrick Harrison Our customer base now extends through To see the laser machinery in operation Injection, blow, extrusion and rotational or to satisfy your queries related to laser moulds, pharmaceutical, Aerospace and engraving any special materials or indeed medical industry, gun manufacturers, general discussion relating to your project printing, ceramic plus other general and then call for an appointment. obscure requests. 3D Lasertec Ltd are privately owned and The need for laser engraving on projects established in February 1999. -

CAD/CAM Selection for Small Manufacturing Companies

CAD/CAM SELECTION FOR SMALL MANUFACTURING COMPANIES By Tim Mercer A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Management Technology Approved for Completion of 3 Semester Credits INMGT 735 Research Advisor The Graduate College University of Wisconsin May 2000 The Graduate School University of Wisconsin - Stout Menomonie, WI 54751 Abstract Mercer Timothy B. CAD/CAM Selection for Small Manufacturing Companies Master of Science in Management Technology Linards Stradins 2/2000 71 pages Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association In today's fast paced world, CAD/CAM systems have become an essential element in manufacturing companies throughout the world. Technology and communication are changing rapidly, driving business methods for organizations and requiring capitalization in order to maintain competitiveness. Knowledge prior to investing into a system is crucial in order to maximize the benefits received from changing CAD/CAM systems. The purpose of this study is to create a methodology to aid small manufacturing companies in selecting a CAD/CAM system. The objectives are to collect data on CAD/CAM systems that are available in the market today, identify important criteria in system selection, and identify company evaluation parameters. Acknowledgements Thanks to Dr. Rich Rothaupt for introducing me to CAM, survey help, and providing guidance with CAD/CAM applications. Thanks to Dr. Martha Wilson for early revisions, survey help and overall guidance. Thanks to my good friend and soon to be Dr. Linards Stradins for his patience, leadership, and wisdom. His invaluable knowledge and dedication as my advisor has helped me both personally and academically. -

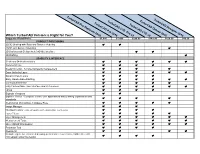

Which Turbocad Version Is Right for You?

TurboCAD Pro Platinum 2016 TurboCAD Designer 2016 TurboCAD LTE Pro v9 TurboCAD Deluxe 2016 TurboCAD Pro 2016 TurboCAD LTE v9 Which TurboCAD Version is Right for You? Suggested Retail Price $1,695 $1,495 $299.99 $149.99 $129.99 $49.99 PRODUCT POSITIONING 2D/3D Drafting with Solid and Surface Modeling a a 2D/3D with Surface Modeling a 2D Drafting with Default AutoCAD-like Interface a a 2D Drafting a USABILITY & INTERFACE 32-bit and 64-bit bit versions a a a a a a Command Line a a a a Design Director - for object property management a a a a Draw Order by Layer a a a a a a Dynamic Input Cursor a a a a Easy, Handle-Based Editing a a a a a a Conceptual Selector a a a a a Fully Customizable User Interface and Preferences a a a a a a ePack a a a a Explode Viewports a a Explorer Palette - Complete control over applicationa and Drawing organization and a a a a standards Geolocation of drawings, Compase Rose a a a a a Image Manager a a a Intelligent Cursor - data entry points and feedback visible next to cursor a a a a Layer Filters a a a a a Layer Management a a a a a a Measurement Tools a a a a a a Object SNAP Prioritization a a a a a a Protractor Tool a a a a Flexible UI a a a a Redsdk engine for enhanced drawing performance in wireframe, hidden line and a a a a conceptual rendering viewing TurboCAD Pro Platinum 2016 TurboCAD Designer 2016 TurboCAD LTE Pro v9 TurboCAD Deluxe 2016 TurboCAD Pro 2016 TurboCAD LTE v9 Which TurboCAD Version is Right for You? Transparent and Bit-mapped Fills a a a a True Units Retained between Drawings with Different -

Date Created Size MB . تماس بگیر ید 09353344788

Name Software ( Search List Ctrl+F ) Date created Size MB برای سفارش هر یک از نرم افزارها با شماره 09123125449 - 09353344788 تماس بگ ریید . \1\ Simulia Abaqus 6.6.3 2013-06-10 435.07 Files: 1 Size: 456,200,192 Bytes (435.07 MB) \2\ Simulia Abaqus 6.7 EF 2013-06-10 1451.76 Files: 1 Size: 1,522,278,400 Bytes (1451.76 MB) \3\ Simulia Abaqus 6.7.1 2013-06-10 584.92 Files: 1 Size: 613,330,944 Bytes (584.92 MB) \4\ Simulia Abaqus 6.8.1 2013-06-10 3732.38 Files: 1 Size: 3,913,689,088 Bytes (3732.38 MB) \5\ Simulia Abaqus 6.9 EF1 2017-09-28 3411.59 Files: 1 Size: 3,577,307,136 Bytes (3411.59 MB) \6\ Simulia Abaqus 6.9 2013-06-10 2462.25 Simulia Abaqus Doc 6.9 2013-06-10 1853.34 Files: 2 Size: 4,525,230,080 Bytes (4315.60 MB) \7\ Simulia Abaqus 6.9.3 DVD 1 2013-06-11 2463.45 Simulia Abaqus 6.9.3 DVD 2 2013-06-11 1852.51 Files: 2 Size: 4,525,611,008 Bytes (4315.96 MB) \8\ Simulia Abaqus 6.10.1 With Documation 2017-09-28 3310.64 Files: 1 Size: 3,471,454,208 Bytes (3310.64 MB) \9\ Simulia Abaqus 6.10.1.5 2013-06-13 2197.95 Files: 1 Size: 2,304,712,704 Bytes (2197.95 MB) \10\ Simulia Abaqus 6.11 32BIT 2013-06-18 1162.57 Files: 1 Size: 1,219,045,376 Bytes (1162.57 MB) \11\ Simulia Abaqus 6.11 For CATIA V5-6R2012 2013-06-09 759.02 Files: 1 Size: 795,893,760 Bytes (759.02 MB) \12\ Simulia Abaqus 6.11.1 PR3 32-64BIT 2013-06-10 3514.38 Files: 1 Size: 3,685,099,520 Bytes (3514.38 MB) \13\ Simulia Abaqus 6.11.3 2013-06-09 3529.41 Files: 1 Size: 3,700,856,832 Bytes (3529.41 MB) \14\ Simulia Abaqus 6.12.1 2013-06-10 3166.30 Files: 1 Size: 3,320,102,912 Bytes -

![Paper We Present an Early User Evaluation of a Advances in Sketch-Based Modeling Are Set to Simplify Many Sketch-Based 3D Modeling Tool We Have Been Developing [7,8]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9999/paper-we-present-an-early-user-evaluation-of-a-advances-in-sketch-based-modeling-are-set-to-simplify-many-sketch-based-3d-modeling-tool-we-have-been-developing-7-8-209999.webp)

Paper We Present an Early User Evaluation of a Advances in Sketch-Based Modeling Are Set to Simplify Many Sketch-Based 3D Modeling Tool We Have Been Developing [7,8]

ARTICLE IN PRESS Computers & Graphics 31 (2007) 580–597 www.elsevier.com/locate/cag Calligraphic Interfaces An evaluation of user experience with a sketch-based 3D modeling system Levent Burak KaraÃ, Kenji Shimada, Sarah D. Marmalefsky Mechanical Engineering Department, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA Abstract With the availability of pen-enabled digital hardware, sketch-based 3D modeling is becoming an increasingly attractive alternative to traditional methods in many design environments. To date, a variety of methodologies and implemented systems have been proposed that all seek to make sketching the primary interaction method for 3D geometric modeling. While many of these methods are promising, a general lack of end user evaluations makes it difficult to assess and improve upon these methods. Based on our ongoing work, we present the usage and a user evaluation of a sketch-based 3D modeling tool we have been developing for industrial styling design. The study investigates the usability of our techniques in the hands of non-experts by gauging (1) the speed with which users can comprehend and adopt to constituent modeling steps, and (2) how effectively users can utilize the newly learned skills to design 3D models. Our observations and users’ feedback indicate that overall users could learn the investigated techniques relatively easily and put them in use immediately. However, users pointed out several usability and technical issues such as difficulty in mode selection and lack of sophisticated surface modeling tools as some of the key limitations of the current system. We believe the lessons learned from this study can be used in the development of more powerful and satisfying sketch-based modeling tools in the future. -

Standards for Computer Aided Manufacturing

//? VCr ~ / Ct & AFML-TR-77-145 )R^ yc ' )f f.3 Standards for Computer Aided Manufacturing Office of Developmental Automation and Control Technology Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology National Bureau of Standards Washington, D.C. 20234 January 1977 Final Technical Report, March— December 1977 Distribution limited to U.S. Government agencies only; Test and Evaluation Data; Statement applied November 1976. Other requests for this document must be referred to AFML/LTC, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio 45433 Manufacturing Technology Division Air Force Materials Laboratory Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio 45433 . NOTICES When Government drawings, specifications, or other data are used for any purpose other than in connection with a definitely related Government procurement opera- tion, the United States Government thereby incurs no responsibility nor any obligation whatsoever; and the fact that the Government may have formulated, furnished, or in any way supplied the said drawing, specification, or other data, is not to be regarded by implication or otherwise as in any manner licensing the holder or any person or corporation, or conveying any rights or permission to manufacture, use, or sell any patented invention that may in any way be related thereto Copies of this report should not be returned unless return is required by security considerations, contractual obligations, or notice on a specified document This final report was submitted by the National Bureau of Standards under military interdepartmental procurement request FY1457-76 -00369 , "Manufacturing Methods Project on Standards for Computer Aided Manufacturing." This technical report has been reviewed and is approved for publication. FOR THE COMMANDER: DtiWJNlb L. -

Repository for Design 1997 2

Compriler-Aided Design. Vol. 29, No. 12. pp. 895-905, 1997 Published by Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain PII: SOOlO-4485(97)00028.6 0010.4485/97/$17.00+0.00 Research Report A repository for design, process planning and assembly William C Regli*t and Daniel M Gaines* for collaboration, allowing, researchers to post challenge This paper provides an introduction to the Design, Planning and problems to a wide audience, share results, or perform Assembly Repository available through the National Institute of larger-scale experiments requiring bigger data sets with Standards and Technology (NIST). The goal of the Repository is to industrially relevant data. It is our belief that establishment provide a publically accessible collection of 2D and 3D CAD and of this Internet-enabled communal library will hasten solid models from industry problems. In this way, research and advances in solid modeling and application areas such as development efforts can obtain and share examples, focus on manufacturing process planning, feature recognition, and benchmarks, and identify areas of research need. The Repository is assembly planning. available through the World Wide Web at URL http : / / The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 overviews www.parts.nist.gov/parts. Publishedby Elsevierkience the current status and content of the Repository, describing Ltd the manufacturing domains it covers and giving a number of examples. Section 3 discusses research issues that either Keywords: solid modeling, CAD, feature recognition, feature- emerged during development and population of the based manufacturing, manufacturing process planning, Repository and outlines some of the new problems which assembly planning can be addressed based on the Repository’s contents. -

3D Direct Modeling Software

3D Direct Modeling Software MASTER YOUR GEOMETRY 1 Benefits 3 Animation 3 Rack & Pinion Constraint 3 Universal Joint Constraint 3 Point on curve constraint 4 Intermittent Motor Dialog 4 CAD Comparison 5 Photorealistic Rendering 6 File Open/Load Performance 6 Table of Contents Table Sheet Metal Flange 6 Interoperability 7 ACIS SAT/SAB R25 7 Inventor Version 2015 7 AutoCAD DWG/DXF 2015 7 CATIA V5 R24 7 Other Features and Improvements 7 3D Direct Modeling Software MASTER YOUR GEOMETRY 2 Benefits KeyCreator 2015 continues to add functionality and customer-driven enhancements to give its users unmatched productivity and flexibility for an efficient design-to-manufacture process. As the only remaining independent Direct CAD solution available, KeyCreator extends its use of Direct Modeling technology by now including KeyCreator Compare CAD Comparison tool as a standard feature. KeyCreator 2015 also includes many updates to file reading capabilities to support the latest file versions from major CAD vendors. Animation Enhanced Animation capabilities include: • Rack & Pinion Constraint • Universal Joint Constraint • Point on Curve Constraint • Intermittent Motor Dialog Users can now Export a Movie File of their animation replay for easier sharing. Several new and updated tutorial videos are also available on Kubotek University. Rack and Pinion Constraint example Universal Joint Constraint example 3D Direct Modeling Software MASTER YOUR GEOMETRY 3 Point on Curve Constraint example Intermittent Motor Dialog example 3D Direct Modeling Software MASTER YOUR GEOMETRY 4 CAD Comparison KeyCreator Compare has been enhanced and is now a standard tool found in KeyCreator 2015, making KeyCreator the first and only CAD system that can import, edit and compare dozens of native CAD files produced from other systems. -

HCI Remixed : Essays on Works That Have Influenced the HCI

4 Drawing on SketchPad: Refl ections on Computer Science and HCI Joseph A. Konstan University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S.A. I. Sutherland, 1963: “Sketchpad: A Man–Machine Graphical Communication System” Sutherland’s SketchPad system, paper, and dissertation provide, for me, the answer to the oft-asked question: “why should HCI belong in a computer science program?” I fi rst came across the paper “SketchPad: A Man–Machine Graphical Communica- tion System” from the 1963 AFIPS conference nearly thirty years after it had been published (Sutherland 1963). I was nearing completion of my own dissertation in which I was exploring a variety of techniques for constructing user interface toolkits. At the time, the paper seemed little more than a handy reference in which I could trace the lineage of constraint programming in user interfaces—from Sketchpad, through Borning’s ThingLab (Borning 1981), to my own work, with various hops and detours along the way. I guess I was young and in a hurry. It was only a few years later when I started to teach this material that I realized how much of today’s computing traces its roots to Sutherland’s work. What was this tremendous paper about? A drawing program. Not just any drawing program, but one that took full advantage of computing, a million-pixel display (albeit with a slow pixel-by-pixel refresh), a light pen, and various buttons and dials to empower users to draw and repeat patterns, to integrate constraints with draw- ings so as to better understand mechanical systems, and to draw circuit diagrams as input to simulators. -

Metadefender Core V4.12.2

MetaDefender Core v4.12.2 © 2018 OPSWAT, Inc. All rights reserved. OPSWAT®, MetadefenderTM and the OPSWAT logo are trademarks of OPSWAT, Inc. All other trademarks, trade names, service marks, service names, and images mentioned and/or used herein belong to their respective owners. Table of Contents About This Guide 13 Key Features of Metadefender Core 14 1. Quick Start with Metadefender Core 15 1.1. Installation 15 Operating system invariant initial steps 15 Basic setup 16 1.1.1. Configuration wizard 16 1.2. License Activation 21 1.3. Scan Files with Metadefender Core 21 2. Installing or Upgrading Metadefender Core 22 2.1. Recommended System Requirements 22 System Requirements For Server 22 Browser Requirements for the Metadefender Core Management Console 24 2.2. Installing Metadefender 25 Installation 25 Installation notes 25 2.2.1. Installing Metadefender Core using command line 26 2.2.2. Installing Metadefender Core using the Install Wizard 27 2.3. Upgrading MetaDefender Core 27 Upgrading from MetaDefender Core 3.x 27 Upgrading from MetaDefender Core 4.x 28 2.4. Metadefender Core Licensing 28 2.4.1. Activating Metadefender Licenses 28 2.4.2. Checking Your Metadefender Core License 35 2.5. Performance and Load Estimation 36 What to know before reading the results: Some factors that affect performance 36 How test results are calculated 37 Test Reports 37 Performance Report - Multi-Scanning On Linux 37 Performance Report - Multi-Scanning On Windows 41 2.6. Special installation options 46 Use RAMDISK for the tempdirectory 46 3. Configuring Metadefender Core 50 3.1. Management Console 50 3.2.