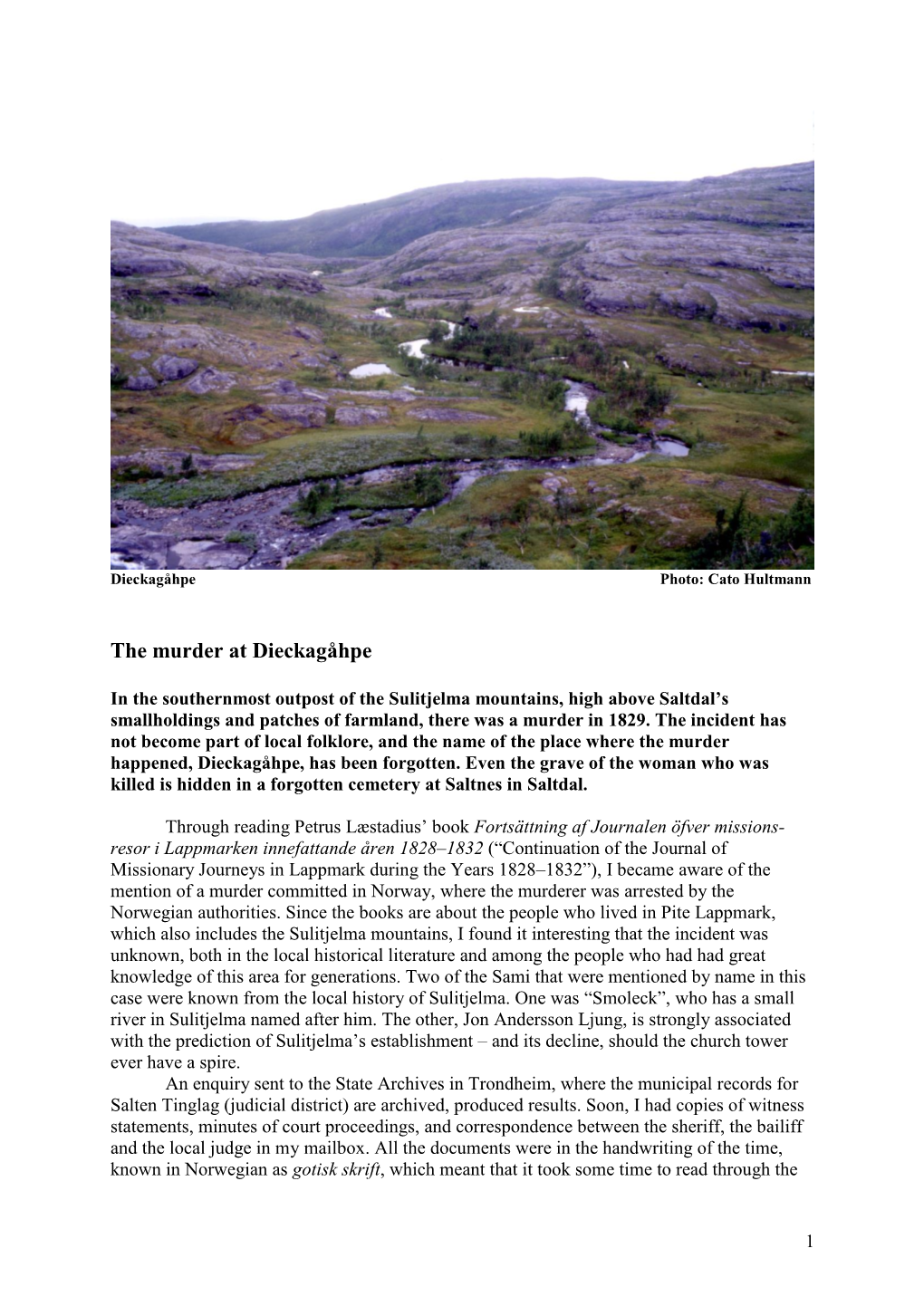

Dette Er Fortellingen Om Et Mord, Noen Neppe Har Hørt Om

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Whole Judgment

SUPREME COURT OF NORWAY On 12 May 2016, the Supreme Court gave judgment in HR-2016-01015-A (case no. 2016/416), criminal case, appeal against judgment A (Counsel Arild Dyngeland) v. The public prosecution authority (Public Prosecutor Per Morten Schjetne) VOTING : (1) Justice Utgård: The case concerns sentence for obstruction of justice in the form of retaliation against five participants in civil cases, see the Penal Code 1902 section 132 a. (2) On 16 March 2015, Lofoten District Court gave judgment concluding as follows: "A, born 00.00.1976, is acquitted of the main indictment count IV. A, born 00.00.1976, is convicted of violation of the Penal Code section 132a subsection 1b, cf. subsection 2, cf. subsection 4 first penal option, the Penal Code section 390a and the Penal Code section 333, all considered against the Penal Code section 62 subsection 1 and section 63 subsection 2, and sentenced to 10 months of imprisonment. Four months of the sentence is to be suspended pursuant to the Penal Code sections 52- 54 with a probation period of 2 years. Credit for time in custody is 5 days." (3) The convicted person appealed to Hålogaland Court of Appeal against the findings of fact in the determination of guilt on all counts. Leave to appeal was granted for the counts concerning the Penal Code 1902 section 132a, but was refused for the counts concerning the Penal Code 1902 section 390a and section 333. The court of appeal stated that the sentence would be reviewed as a result of the partial admission of the appeal against the findings of fact. -

Hemnesberget Ran Orden 12 Nesna Sandnessjøen

GUIDE 2017 – magic and real www.visithelgeland.com R T I G R U T H U E N Slettnes Kinnarodden Gamvik Knivskjelodden Nordkapp Mehamn Omgangs- Gjesværstappan Tu orden stauren Hjelmsøystauren Hornvika Skjøtningberg Kjølnes Helnes Skarsvåg Tanahorn Gjesvær Sværholt- Kjølle ord Kamøyvær Finnkirka MAGERØYA klubben NORDKYN- Kvitnes Berlevåg Sand orden Fruholmen HALVØYA Makkaur H Skips orden ongs orden U Sværholdt K RT HJELMSØYA Sarnes I G R Nordvågen Ki ord Store Molvik Veines U T Ingøy Dy ord Skjånes E N Havøysund Måsøy Honningsvåg Eids orden Kongs ord Sylte ordstauran Gunnarnes Hopseidet Hops orden Tu ord Båts ord Hamningberg Troll ord/ a v Kå ord Lang ordnes l ROLVSØYA Gulgo e d Sylte ord Sylte orden Selvika r Bak orden Lang orden o Rygge ord SVÆRHOLT- s Hornøya g Lakse orden HALVØYA Nervei Davgejavri n N o E K lva Vardø T Sylte orde U Rolvsøysundet R Laggo Tana orden Qædnja- G Repvåg Oksøy- I Sne ord javri vatnet T R PORSANGER- Store Veidnes Akkar ord U VARANGER- H Slotten HALVØYA Tamsøya Bekkar ord HALVØYA VARANGERHALVØYA Kiberg Revsbotn Lebesby Langnes NASJONALPARK K Forsøl Lille ord Smal orden omag Skippernes Skjånes Sund- J elv a a vatnet Austertana k Revsneshamn Smal ord o Ska Komagvær b l lel Lundhamn s v Helle ord e R I ord l u v Langstrand s Ruste elbma a Hammerfest s v a l e Vestertana lv Nordmannset Iordellet e KVALØYA a Friar ord y Sandøybotn Kokelv Sandlia Lotre 370 moh b Falkeellet Rype ord Smør ord e g Dønnes ord Slettnes r 545 m Sand orden Porsanger orden e Kjerringholmen Akkar ord B Stuorra Gæssejavri Masjokmoen Sørvær Lille -

Baug UBAS8-Artikkel.Pdf (412.9Kb)

UniversityUBAS of Bergen Archaeological Series Nordic Middle Ages – Artefacts, Landscapes and Society. Essays in Honour of Ingvild Øye on her 70th Birthday Irene Baug, Janicke Larsen and Sigrid Samset Mygland (Eds.) 8 2015 UBAS – University of Bergen Archaeological Series 8 Copyright: Authors, 2015 University of Bergen, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion P.O. Box 7800 NO-5020 Bergen NORWAY ISBN: 978-82-90273-89-2 UBAS 8 UBAS: ISSN 089-6058 Editors of this book Irene Baug, Janicke Larsen and Sigrid Samset Mygland Editors of the series UBAS Nils Anfinset Knut Andreas Bergsvik Søren Diinhoff Alf Tore Hommedal Layout Christian Bakke, Communication division, University of Bergen Cover: Arkikon, www.arkikon.no Print 07 Media as Peter Møllers vei 8 Postboks 178 Økern 0509 Oslo Paper: 130 g Galerie Art Silk H Typography: Adobe Garamond Pro and Myriad Pro Irene Baug Stones for Bread. Regional Differences and Changes in Scandinavian Food Traditions Related to the Use of Quernstones, Bakestones and Soapstone Vessels c. AD 800–1500 Quernstones, bakestones and soapstone vessels represent everyday products related to food processing in prehistory; for centuries, these artefacts comprised important parts of the Scandinavian household. Throughout history, grain and grain products have been an indispensable source of food, with bread and porridge as vital elements. In the Middle Ages, up to 80 per cent of the consumption could stem from grain and grain products (Øye 2002, 323, 406). To make grain digestible it had to be crushed and, for this, querns and quernstones were needed. Bakestones were necessary for baking bread over the hearth, and soapstone vessels were important for making porridge. -

Minerals from the the Sulitjelma Copper Mines, North Norway

Kongsberg MineralsVmposium 1999 Norsk Bergverksmuseum Skrift, 15,47-56 Minerals from the the Sulitjelma Copper Mines, North Norway Fred Steinar Nordrum The Sulitjelma Copper Mines (1891-1991) Mining history ranks as the largest mining enterprise in The first deposit discovered in SUlitjelma Norway in the 20th centrury. DUring the was found by a lapp, Mons Petter, about mining operations and also later, fine 1858. The Swedish consul Nils Persson mineral specimens have been collected in was granted a mining lease in 1886, and the district. after investigations and preliminary mining from 1887 he established a mining Introduction company, the Sulitelma Aktiebolag, in Copper has been mined in Norway for 1891. The Sulitjelma mines became the several hundred years, the first largest mining enterprise in Norway in the documented copper mine being the 20th century, with an estimate of 75 000 Verlohrne Sohn Mine in Kongsberg 1490. man years of labour. The largest number of Several types of copper ore deposits have employees was reached in 1913, been exploited, but the major ore type has amounting to 1 737. The company was been the Caledonian, massive, strata reorganized in 1933, under the name of bound sulphide deposits. Vigsnes, Stordl2J, AJS Sulitjelma Gruber, and from 1937 the Folldal, Rl2Jros, Ll2Jkken, and Grong are major shareholders were Norwegians. The other well-known ore districts with deposits mining operations ended June 28, 1991. of this type. In this paper, however, the Sulitjelma district will be focused on. It is Figur 1. Simplified geological map of the situated about 80 km east-southeast of the Su/itjelma area with the location ofthe most town Bodl2J in Nordland county. -

Lappland Kraftverk I Sulitjelma, Fauske Kommune

25.03.2019 Prosjektbeskrivelse Lappland kraftverk i Sulitjelma, Fauske kommune Lappland kraftverk Etablering av samisk grenseoverskridende miljø- og naturvennlig vannkraftutbygging for utvikling av det lokale næringslivet, kulturen og eksisterende tettsteder i Nordland og Norrlands inland. Etableringen er basert på svenske vannkraftressurser, fallrettighet interesse, særlige samiske rettigheter etter svensk lovgivning, norsk lovgivning, og norsk innsatsområde, natur, miljø og samfunnet. Styret: Sjøgata 38, 8006 Bodø. Tlf: 75 51 88 00 | Mob: 93 01 88 20 | E-post: [email protected] | Org.nr. NO 829235412 Nettilknytning av Lappland kraftverk Fauske og Sørfold kommuner, Norge Jokkmokk og Arjeplog kommuner, Sverige Laponia Center AB og MuskenSenter AS har fremlagt melding om planer for en ny 420 kV nettilknytning – alternativt jordkabel eller kraftledning – fra Lappland kraftstasjon til Seitevarre/Heliga fallet i Jokkmokk kommune, som første byggetrinn/fase 1 prosjekt. Den elkraft som skal produseres ved Lappland kraftverk – av svenske vannkraftressurser - skal tilbakeføres til Sverige, til det svenske sentralnettet i Jokkmokk, på grunn av faktiske forhold, som deriblant; a. Sentralnettet i Salten regionen – Salten trafo – har ikke nettilknytnings kapasitet for planlagt kraftproduksjon fra Lappland kraftverk. b. Grunnlaget som gjelder for Sveriges ”samtykke» til norsk konsesjon for bygging av Lappland kraftverk, er basert på bestemmelsene som deriblant; • Art. 12, 1 og Art. 14, 1, 2 og 3 i «Konvensjon mellom Norge og Sverige av 11. mai 1929». • Miljöbalk (1989:808) under §§ 2-8 og spesielt om bestemmelsen «för utvecklingen av … det lokala näringslivet», • Rådighet över mark- och vatten» Lag 1971:437, ”tilkommer den samiska befolkningen .. / Den som er av samisk härkomst (same) .. till underhåll för sig och sina renar . -

The Geology of the Northern Sulitjelma Area and Its Relationship to the Sulitjelma Ophiolite

The geology of the northern Sulitjelma area and its relationship to the Sulitjelma Ophiolite MICHAEL F. BILLETI Billett, M. F.: The geology of the northern Sulitjelma area and its relationship to the Sulitjelma Ophiolite, Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 67, pp. 71-83. Oslo 1987. ISSN 0029-196X. The geology of the area to the north of Sulitjelma is dominated by the Skaiti Supergroup, which occurs at the top of the Upper Allochthon beneath overthrust rocks of the Uppermost Allochthon. The regional geology comprises a locally inverted, stratified ophiolite, the Sulitjelma Ophiolite, which partly intrudes the overlying rocks of the Skaiti Supergroup. These older higher grade rocks consist of a continuous l km thick sequence of gneisses, quartzites, semipelites, graphitic and calcareous schists, which are associated with several levels of metaigneous rocks. The most important of these are the Rupsielven Amphibolites, which are geochemically analogous to within-plate oceanic island basalts and are therefore distinct from the metabasic rocks of the Sulitjelma Ophiolite. The main period of regional deformation and metamorphism occurred during the Scandian event of the Caledonian Orogeny. Evidence is presented to show that the older metasediments and metabasites of the Supergroup retain the signa ture of an earlier orogenic event of possible Finnmarkian age or older. The Skaiti Supergroup therefore represents a fragment of pre-Scandian continental crust through which the ophiolitic rocks were originally intruded and onto which they were locally erupted. M. F. Billett, Department of Soil Science, University of Aberdeen, Meston Walk, Aberdeen, AB9 2UE, Scotland. The Sulitjelma area (67° 10'N, 15" 21' S) is situated the Skaiti Supergroup after an area to the south approximately 70 km north of the Arctic Circle (Boyle et al. -

Operations and Company Update Sulitjelma Copper Zinc Project

283 Rokeby Road Subiaco WA 6008 P: +61 8 6141 3500 F: +61 8 9481 1947 E: [email protected] 6 March 2017 Operations and Company Update Drake Resources Limited (Drake, or the Company) provides this update to the market concerning its base metal projects in Scandinavia: • Sulitjelma, Norway • Joma-Gjersvik, Norway • Granmuren, Sweden Drake has maintained its interest in the tenements making up these projects in good standing since 2016 and has where necessary applied for renewal of relevant tenements. The Company is awaiting confirmation of the renewal of one of its tenements, Tullsta nr 1, but expects to receive this in due course. The Company has today released a Notice of Meeting in relation to its proposed capital raising and recapitalisation. Reinstatement of the Company’s securities to trading on ASX will be subject to completion of the capital raising. Subject to successful completion of the capital raising, Drake proposes to devote a total amount of up to approximately $500,000 to evaluation and exploration activities in respect of its three base metal projects during 2017. The exact amount of exploration expenditure will depend on, among other things, access to funds, exploration results, and any other financial commitments. (The expenditure under the 2017 program can be carried out regardless of when the renewal of the Tullsta nr 1 tenement area is received ,and the amount, if any, that it commits to the Joma joint venture.) A summary of the Company’s activities on these projects and its proposed exploration activities in respect of each of them is set out below. -

Censorbooklet Jbs.Pdf (5.577Mb)

Sulisjælbmá A TRANSFORMATION OF THE REMNANTS OF A MINING SOCIETY CENSOR BOOKLET JOHAN BY SØRHEIM SUPERVISED BY ERIK FENSTAD LANGDALEN 1 2 Intro Sulitjelma...............................................1-2 The theme of my diploma is reuse of abondoned The new industry .....................................3-4 mining facilities. In my project I propose the The situation...........................................5-6 transformation of Knuseriet, a remaining structure from the mining industry in Sulitjelma. The structure...........................................7-8 My approach to this project will be to work with the The program..........................................9-10 existing structure in a way where it will be Materiality and reuse.............................. 11-12 appreciated for what it is. This strategy can be justified both by the costs to remove such large concrete struc- The concept....... .................................13-14 tures, while at the same time deleting a part of their local history. The layout......... .................................15-16 Section............ ..................................17-18 The process - main room...........................19-20 The process - sleeping units........................21-22 1 2 Sulitjelma and it’s mining past Sulitjelma is situated in a lush valley in Fauske com- mune. Easily accessible due to its proximity to Bodø, kautokeino where air, train and waterborne traffic make the rest of the world feel close. But the journey hasn’t always been this simple. The first Norwegian family settled in 1848, and ten years later the first discovery of copper was done. Without the tunnels that later opened the area to the outside world, the area was difficult to access and the mining operation was delayed until 1891. The business grew rapidly, and after the turn of the century it was Norway’s second largest industrial company, with 1750 employees. -

2/21 Request AO EN

EFTA Court Doc 56 1 rue du Fort Thüngen L-1499 Luxembourg Luxembourg Case No 20-183236SIV-HRET, civil case, appeal against judgment: Request for an Advisory Opinion 1. INTRODUCTION (1) Pursuant to Article 34 of the Agreement between the EFTA States on the Establishment of a Surveillance Authority and a Court of Justice (SCA), read in conjunction with section 51a of the Norwegian Courts of Justice Act (Lov om domstolene), the Supreme Court of Norway (Norges Høyesterett) hereby requests an Advisory Opinion from the EFTA Court for use in Case No 20-183236SIV-HRET. The appellant in the case is Norep AS, whilst the respondent is Haugen Gruppen AS. (2) The case concerns Norep AS’s claim for remuneration upon termination of a contract under the Norwegian legislation on commercial agents. That claim was not successful before the District Court or the Court of Appeal in their judgments on the ground that Norep AS could not be deemed to be a “commercial agent” as defined in the first paragraph of section 1 of that legislation. (3) The case raises questions of interpretation of Council Directive 86/653/EEC of 18 December 1986 on the coordination of the laws of the Member States relating to self-employed commercial agents (“the Directive”). Those rules are implemented in Norwegian law by Law of 19 June 1992 on commercial agents and business travellers (“the Commercial Agents Act”) (lov om handelsagenter og handelsreisende (agenturloven) 19. juni 1992). (4) The Supreme Court now requests the EFTA Court to give an Advisory Opinion on the precise substance of the rule laid down in the first option under Article 1(2) of the Directive, more specifically the term “negotiate”. -

NGU Rapport 2001.88 (Rein 2001)

Norges geologiske undersøkelse 7491 TRONDHEIM Tlf. 73 90 40 00 Telefaks 73 92 16 20 RAPPORT Rapport nr.: 2002.068 ISSN 0800-3416 Gradering: Åpen Tittel: Mineral- og masseforekomster - konsekvensutredning i Junkerdal/Balvatn Forfatter: Oppdragsgiver: Jan Sverre Sandstad Fylkesmannen i Nordland Fylke: Kommune: Nordland Saltdal og Fauske Kartblad (M=1:250.000) Kartbladnr. og -navn (M=1:50.000) Saltdal og Sulitjelma Forekomstens navn og koordinater: Sidetall: 21 Pris: Kartbilag: 2 Feltarbeid utført: Rapportdato: Prosjektnr.: Ansvarlig: 25.06.2002 2725.00 Sammendrag: Muligheten for økonomisk utnyttbare mineralressurser innenfor utredningsområdet for 'Bruks- og verneplan for Junkerdal/Balvatn' er beskrevet. I tre områder, Kong Oscar sonen, Balddoaivi-synformen og Skaitidalen, er konsekvensen av vern mot mulig utnyttelse av mineralressurser vurdert nærmere, samt at avbøtende tiltak gjennom justering av vernegrensen i forhold til utredningsområdet er foreslått. I tillegg er det gitt kommentarer på mindre justeringer av grensen. I Kong Oscar sonen er det gull som har størst økonomisk interesse, med eventuelle bidrag fra andre metaller som kobber, bly og sink. Hele sonen bør undersøkes grundig for å bestemme det økonomiske potensialet. I Balddoaivi-synformen finnes trolig store mengder kobber og andre metaller som ikke er økonomisk utnyttbare med dagens gruveteknologi. Under verneplanarbeidet bør det tas hensyn til en mulig utvinning av disse ressursene med alternativ teknologi i framtida. Skifer i Skaitidalen er av god kvalitet og bør kartlegges nærmere. Det er ikke gjort forsøk på å gi noen tall verken på produksjonsverdi eller antall arbeidsplasser. Malmressursene vil være av nasjonal interesse hvis de lar seg utnytte økonomisk, mens skiferen i Skaiti kan ha både lokal og regional betydning. -

Naturfaglige Undersøkelser I Faulvatn-Området I Forbindelse Med

019 Naturfagligeundersøkelser i Faulvatn-områdeti forbindelse med konsesjonssøknad LarsErikstad Gunnar Halvorsen Harald Korsmo Harald H. Bergmann BjørnWalseng NINA NORSK NSnTUTT FOR NATUZF'ORSI(NNG Naturfagligeundersøkelseri Faulvatn-områdeti forbindelse med konsesjonssøknad LarsErikstad Gunnar Halvorsen Harald Korsmo Harald H. Bergmann Bjørn Walseng NORSKINSTITUTTFORNATURFORSI(NNG nina utredning 019 Erikstad,L., Halvorsen,G., Korsmo, H., Bergmann,H.H. & Wal- NINAs publikasjoner seng,B. Naturfaglige undersøkelseri Faulvatn-områdeti forbindelsemed ,NINAutgir seksulike faste publikasjoner: konsesjonssøknad NINAUtredning 19: 1-41 NINA Forskningsrapport Her publiseresresultater av NINAs eget forskningsarbeid, i Ås-NLH,mars 1991 den hensiktå spreforskningsresultaterfra institusjonentil et større publikum. Forskningsrapporterutgis som et alternativ ISSN0802-3107 til internasjonal publisering, der tidsaspekt, materialets art, ISBN82-426-0112-7 målgruppemm. gjør dette nødvendig. NINA Utredning Klassifiseringavpublikasjonen: Serien omfatter problemoversikter, kartlegging av kunn- Norsk:Vassdragsutbyggingogandre tekniskeinngrep skapsnivåetinnen et emne, litteraturstudier, sammenstilling Engelsk:Hydro-power construction and other technicaldevelop- av andresmaterialeog annet som ikke primært er et resultat ment av NINAsegenforskningsaktivitet. Rettighetshaver: NINA Oppdragsmelding NINANorskinstitutt for naturforskning Dette er det minimum av rapportering som NINAgir til opp- dragsgiveretter fullført forsknings- eller utredningsprosjekt. Publikasjonenkansiteresfritt -

The Scope for Norwegian Commitments Related to International Research on Jan Mayen Island

Chapter 25 NATO Advanced Research Workshop The Scope for Norwegian Commitments Related to International Research on Jan Mayen Island Odd Gunnar Skagestad Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The main considerations that will govern the scope for Norwegian commitments related to international research operations on Jan Mayen Island are: 1) the physical characteristics of Jan Mayen Island, 2) its legal status in terms of international law as well as national legislation, 3) infrastructure and logistics, and 4) national policies concerning research or related activities. Any Norwegian support to proposed international research activities will require that the operation would be compatible with existing or prospective Norwegian national policies or strategies concerning research or related activities, which could entail the possibility of cooperation with key Norwegian research institutions. Key words: Norwegian sovereignty, legal obstacles, access regime, environmental protection, regulations, Action Plan 1. INTRODUCTION As a point of departure in describing the scope for Norwegian commitments related to international research operations on Jan Mayen Island, one will note that there are very few, if any, pre-ordained restrictions limiting the scope of operations that can be contemplated, subject to such variables as one's imagination, the financial resources at one's disposal, and one's priorities. However, there will always be a number of considerations that will narrow down the realistically available options and provide the more or less rigid modalities for the kind of activities that would seem 269 S. Skreslet (ed.), Jan Mayen Island in Scientific Focus, 1-10. © 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.