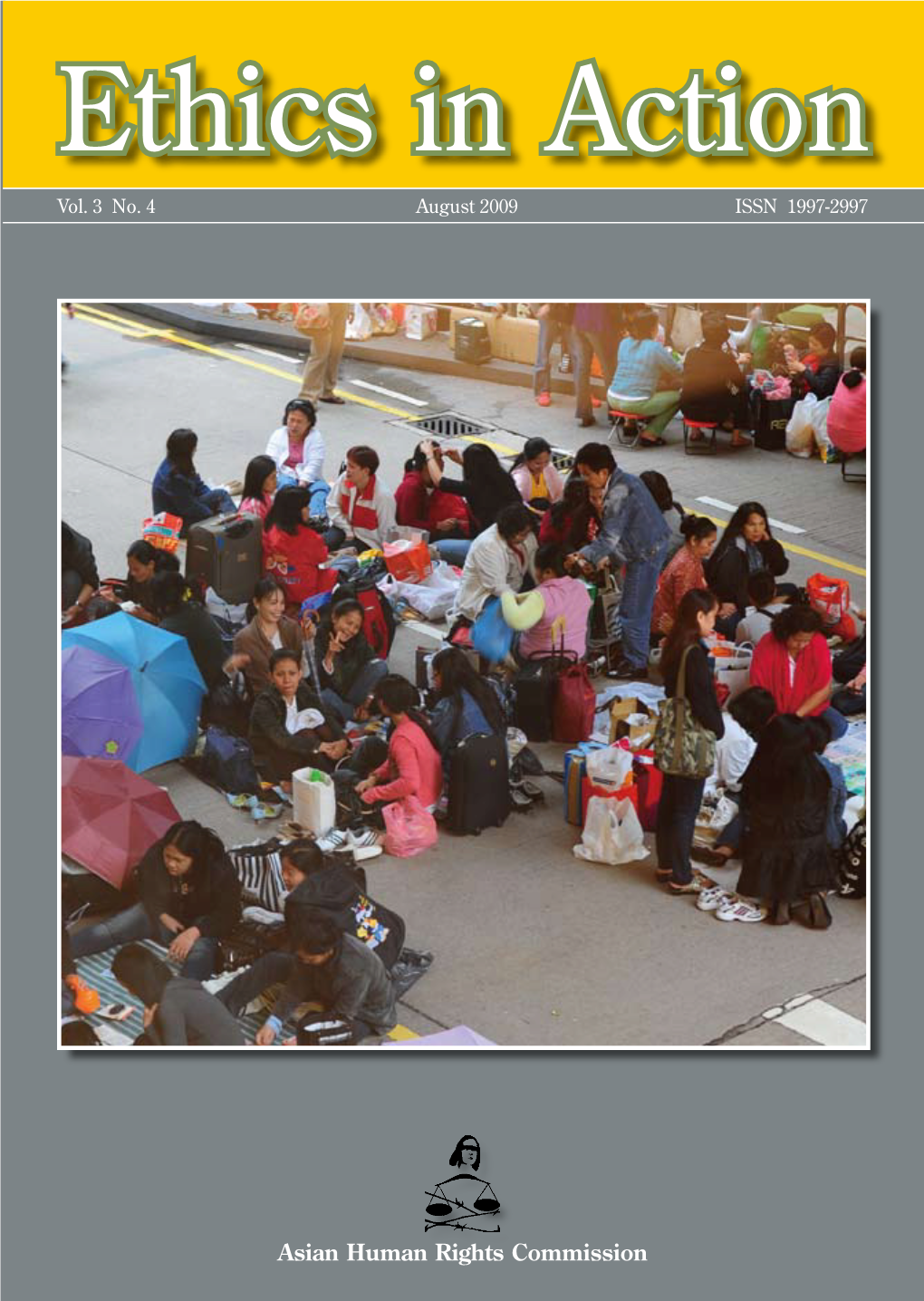

Ethics in Action Ethics in Action Begins with the Realization That Both Law and Morality Have Failed Ethics in Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 6, B.E. 2560 (2017) Regarding Control of Transport of Animal Feed Corn ------------------------------------ Whereas the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has repealed the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 1, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Determination of Goods and Services under Control dated 21 January B.E. 2559 ( 2016) , resulting in the end of enforcement of the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 6, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Control of Transport of Animal Feed dated 25 January B.E. 2559 (2016). In the meantime, the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has already reconsidered the exercise of its power regarding the stipulation of the aforesaid measure, it is of the view that the measure of the control of transport of animal feed corn should be maintained in order to bring about the fairness of price, quantity and the maintenance of stability of the animal feed market system within the Kingdom. By virtue of Section 9 (2) and Section 25 (4), (7) of the Price of Goods and Services Act, B.E. 2542 ( 1999) , the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has therefore issued this Notification, as follows. Article 1. This Notification shall come into force in all areas of the Kingdom for the period of one year as from the day following the date of its publication.1 Article 2. It is prohibited for a person to transport animal feed corn, whereby -

Pak Mun Dam Case Study

Introduction: Pak Mun Dam Case Study As part of a two-year work programme to review the development effectiveness of large dams, The World Commission on Dams (WCD) has commissioned TDRI to lead the case study on Pak Mun dam on the Mun river in Thailand’s northeast. Pak Mun was selected as one of the case studies on dams located in major river basins in different regions of the world. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) started construction of Pak Mun dam in June 1990, and has been operating Pak Mun as a run-of-the-river hydropower project since 1994. TDRI was assigned to re-examine the premises of the underlying economic case for Pak Mun, and to review the project’s justification in the light of material evidence and developments to date bearing on its impact on the environment, in particular on fisheries. WCD’s mandate is to propose a framework for weighing the alternatives in water resources and energy management, and to set internationally acceptable criteria in the planning, design, construction, monitoring, operation and decommissioning of dams. WCD’s final report was released on November 16th, 2000 in London. With the issue of its final report, WCD has completed its mandate and was formally decommissioned. Pak Mun case study was part of the knowledge base which supported the Commission’s conclusions. TDRI’s report, which was submitted to WCD in its final form in March 2000, was previously circulated with other commissioned papers to participants at a stakeholders’ meeting convened by WCD in Bangkok on 23rd February, 2000. -

Feature of Pak Chom Hydropower Project

Pre-Feasibility Study And Initial Environmental Examination Two Run-of-River of the Mekong Cascade Project Feasibility Study Pak Chom and Ban Koum Projects 1 Mekong Country Catchment area Catchment area Runoff (km2) (percent) (percent) BasinChina 166,500 20.9 16 Myanmar 22,000 2.7 2 Lao PDR 202,400 25.5 35 Thail and 184,200 23.2 18 Cambodia 154,700 19.5 18 Vi et nam 65,200 8.2 11 Total 795,000 100 100 2 Longitudinal Section Showing the Upper Sites of HydropowerProject Projects Installed capacity (MW) (LancangGONGGUOAIAO River) 750 XIAOWAN 4200 MANWAN 1,550 DACHAOSHAN 1,350 NUOZHADU 5,850 JINGHONG 1,750 GANLANBA 150 MENGSONG 600 Total 16,200 3 Projects Granted Concessions by the Lao and Cambodian Government Luang Prabang Xayaburi Pak Beng Project Installed capacity (MW) Pak Chom Pak Lay 1. Don Sahong Hydropower Project, Khong District, 240 Champasack Province 2. Xayaburi Hydropower Project, Xayaburi Province 1,260 3. Pak Lay Hydropower Project, Xayaburi Province 1,010 4. Pak Beng Hydropower Project, Oudomxay Province 1,230 5. Luang Prabang Hydropower Project, Luang Prabang Province 1,410 6. Sambor Hydropower Project, Kratie Province 3,300 Ban Koum Don Sahong Sambor 4 Hydropower Projects along Thailand-Lao Pak Chom PakPakPRD ChomChom BorderHydropowerHydropower Hydropower ProjectProject Project Located at KM 1651 from the mouth of the Mekong River and adjacent to Ban Huai Khop, Loei Province, Thailand and to Ban Huai Hang, Sangthong District, Ban Koum Hydropower Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Project BanBan KoumKoum HydropowerHydropower ProjectProject -

Islands of the Commons Community Forests and Ecological Security in Northeast Thai Villages

The author agrees to allow the Digital Library of the Commons to add this paper to its archives for IASC conferences. Islands of the Commons Community Forests and Ecological Security in Northeast Thai Villages Wataru Fujita (Konan Women’s University) Abstract: Debates on common property resource management related to sustainable natural resource management in developing countries have concentrated on land and resources with common or communal tenure. However, destructive use of state or private lands and resources may upset the balance of ecosystem and damage ecological services on which local people depend, even when common resources are well managed. It is necessary to consider the mechanisms by which collective action establishes and sustains local ecological security as a kind of common good. In this paper, I consider the meaning of local ecological security by examining the case of community forests and the expansion of cash crops, especially, rubber, in the research site in Northeast Thailand. The expansion of rubber cultivation at a rapid pace damaged local ecological security. Community forests, which are still well managed, are like islands in the sea of the global economy. With special focus on how the villagers have dealt with the changed in their living environment, I consider the collective actions that are necessary to enhance ecological security as a local common good. Key words: Northeast Thailand, community forest, rubber, ecological security Introduction Common property resource management has been at the center of debates related to sustainable natural resource management in developing countries since reports of successful cases were offered to refute Hardin’s argument regarding the “tragedy of commons” [McCay and Acheson eds 1987; Ostrom 1990]. -

Electricity Generation and Distribution in Thailand: Policy Making, Policy Actors and Conflict in the Policy Process

Electricity Generation and Distribution in Thailand: Policy Making, Policy Actors and Conflict in the Policy Process Thanyawat Rattanasak A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Science and Policy The University of New South Wales August 2009 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Project Report Sheet Surname or Family name: RATTANASAK First name: THANY AW AT Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: SOCIAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Faculty: ART AND SOCIAL SCIENCE Title: ELECTRICITY GENERATION AND DISTRIBUTION IN THAILAND: POLICY MAKING, POLICY ACTORS AND CONFLICT IN THE POLICY PROCESS Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis is an analysis of the development of Thailand's electricity industry power generation policy, its institutions and the policy process. It also examines the policy actors ,,working within the process, and their roles, power and influence, factors that have shaped the distinctive characteristics of the electricity industry in Thailand today, an industry that is being confronted by increased opposition to its development from a range of community groups concerned with adverse environmental and social impacts. My research used Historical- Institutionalism and Policy Network Analysis to guide the investigation. A qualitative research methodology, including the examination of documentary evidence and the interviewing of 25 key informants, was used to improve our knowledge of the policy process, and to reveal the nature of the conflicts that have emerged within the Thai policy-making bureaucracy, a bureaucracy that controls the electricity industry, and between these policy actors, the elected and military governments, and other parts of the Thai community. -

A Case Study of Mekong Border Karaoke Settings

Karaoke Discourses: A Case Study of Mekong Border Karaoke Settings Karaoke Discourses: A Case Study of Mekong Border Karaoke Settings Worathanik Photijak* and Savitri Gadhavanij** Abstract This case study provides scene surveys and discourse surveys of the Mekong border karaoke bars in three districts; Khemmarat, Nataan, and Khong Chiam, of Ubon Ratchathani province. This study will illustrate contrastive characteristics of city zone karaoke bars, unique attributes of the Mekong border karaoke bars, as well as highlight the uniqueness of the Mekong border karaoke business. The case study will explore EJTDPVSTFTǰDJSDVMBUJOHǰJOǰUIFǰ.FLPOHǰCPSEFSǰLBSBPLFǰDPNNVOJUJFTǰ5IFǰųOEJOHT reveal that the characteristics of city zone karaoke bars and the Mekong border karaoke bars are different. The Mekong karaoke bars sustain their business viability on hidden sexual services. Khong Chiam karaoke bars are more touristic and systematically managed, however, the sexual service available in the karaoke bars is similarly highlight. The lived experiences of young Laotian karaoke service girls who live BOEǰXPSLǰJOǰUIFǰLBSBPLFǰCBSTǰBSFǰDPOųOFEǰXJUIJOǰDPOEJUJPOTǰPGǰUIFJSǰLBSBPLFǰTFSWJDFǰ and sexual service work. In terms of discourses, there are various discourses produced, maintained, and reproduced within the complex Mekong karaoke communities. In term PGǰJOTUSVDUJPO ǰUIJTǰDBTFǰTUVEZǰEFNPOTUSBUFTǰųFMEXPSLǰQSPDFTTFTǰBDDPSEJOHǰUPǰ/FYVTǰ Analysis method. Keywords: Discourses, Border Karaoke, Karaoke Business, Sex worker, Hidden Prostitution * Graduate School -

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 4, B.E. 2560 (2017) Regarding Control of Transport of Paddy, Rice ------------------------------------ Whereas the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has repealed the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 1, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Determination of Goods and Services under Control dated 21 January B.E. 2559 ( 2016) , resulting in the end of enforcement of the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 4, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Control of Transport of Paddy, Rice dated 25 January B.E. 2559 (2016). In the meantime, the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has already reconsidered the exercise of its power regarding the stipulation of the aforesaid measure, it is of the view that the measure of the control of transport of paddy, rice should be maintained in order to bring about the fairness of price, quantity and the maintenance of stability of the rice market system within the Kingdom. By virtue of Section 9 (2) and Section 25 (4), (7) of the Price of Goods and Services Act, B.E. 2542 ( 1999) , the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has therefore issued this Notification, as follows. Article 1. This Notification shall come into force in all areas of the Kingdom for the period of one year as from the day following the date of its publication.1 Article 2. In this Notification, “rice” means rice, pieces of rice, broken-milled rice. -

Case Study: Pak Mun Dam, Mekong River Basin, Thailand

WCD Case Study Pak Mun Dam Mekong River Basin Thailand Final Report: November 2000 Prepared for the World Commission on Dams (WCD) by: Sakchai Amornsakchai - Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok Philippe Annez - Griffon Ltd., Bangkok Suphat Vongvisessomjai - Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok Sansanee Choowaew - Mahidol University, Bangkok Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI), Bangkok Prasit Kunurat - Department of Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University Jaruwan Nippanon, - Department of Health, Khon Kaen University Roel Schouten- Seatec International - Consulting Engineers, Bangkok Pradit Sripapatrprasite- Seatec International - Consulting Engineers, Bangkok Chayan Vaddhanaphuti - Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai Chavalit Vidthayanon - Royal Thai Government Fisheries Department, Bangkok Wanpen Wirojanagud, - Faculty of Engineering, Khon Kaen University Ek Watana - Department of Ecological Science, Khon Kaen University Secretariat of the World Commission on Dams P.O. Box 16002, Vlaeberg, Cape Town 8018, South Africa Phone: 27 21 426 4000 Fax: 27 21 426 0036. Website: http://www.dams.org E-mail: [email protected] Pak Mun Dam - Mekong River Basin, Thailand i Disclaimer This is a working paper of the World Commission on Dams - the report published herein was prepared for the Commission as part of its information gathering activity. The views, conclusions, and recommendations are not intended to represent the views of the Commission. The Commission's views, conclusions, and recommendations will be set forth in the Commission's own report. Please cite this report as follows: Amornsakchai, S., Annez, P., Vongvisessomjai, S., Choowaew, S., Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI), Kunurat, P., Nippanon, J., Schouten, R., Sripapatrprasite, P., Vaddhanaphuti, C., Vidthayanon, C., Wirojanagud, W., Watana, E. 2000. Pak Mun Dam, Mekong River Basin, Thailand. -

A Lesson Learnt from Pak Mun Dam

Woraya Som-in and Savitri Gadavanij Hydropower Dam and Development, Whose Development and for Whom?: A Lesson Learnt from Pak Mun Dam Woraya Som-in* and Savitri Gadavanij** Abstract Pak Mun hydropower dam is one of several government’s development projects in which emerged from the claim of national security and rural development. Due to the long and continuing protests against Pak Mun Dam, the project is one of the most outstanding cases that capture the interest of the civil society in local, national and international context. The case is also considered as one of the longest social movements by grassroot people in Thailand and the world. In 1991 since the dam was built and up until now, the requests and protests of the Assembly of the Poor (affected people) against Pak Mun dam have continued for more than two decades due to the dam’s severe impact to thousands of livelihoods and the ecology of the Mun River and many local communities at large. The impact of the EBNǰIBTǰBMTPǰHFOFSBUFEǰUIFǰDPOŴJDUTǰBNPOHǰTUBLFIPMEFSTǰJOǰUIFǰTPDJFUZǰ#ZǰDPOEVDUJOHǰ FUIOPHSBQIJDǰTUVEZǰJOǰUIFǰųFMEǰTJUFǰPGǰUIFǰJTTVFǰBMPOHǰXJUIǰFNQJSJDBMǰFWJEFODFT elicited from the community, the study presents the authentic data rooted from the ųMFǰTJUFǰ5IFSFGPSF ǰUIJTǰBSUJDMFǰJTǰBJNJOHǰUPǰTIFEǰMJHIUǰPOǰNBLJOHǰVOEFSTUBOEJOHǰPGǰIPXǰ * Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Mahasarakham University, Khamraing Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham 44150, THAILAND. E-mail: [email protected] ** Graduate School of Language and Communication, National Institute -

A Case Study of Return Migrants from Ubon Ratchathani Province

doi: 10.14456/jms.2017.5 Rural-to-Urban Migrations and the Return of Migrants Back Home: A Case Study of Return Migrants from Ubon Ratchathani Province, Thailand1 Natedao Taotawin Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchathani University, Thailand E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Rural-to-urban migration is a common occurrence in Northeastern Thailand, the region also known as “Isan.” Isan rural villagers, after finishing the rice harvest, regularly migrate to urban areas in Thailand or overseas to seek jobs and additional sources of income. Seasonal migration is a common strategy used by Isan young women to make a living. When they reach middle age, however, women migrants often choose to return to their homes in rural villages to live with their families. This paper examines the experiences of ten Isan rural-to-urban female migrants. These women present their experiences of migration and explain the effects of migration on their identities, values, worldviews and gender roles. They finished primary school and were single and young when they first migrated to urban areas to be factory workers. However, after they had children and reached middle age, most decided to return home to rural areas where they made a living. Therefore, rural-to-urban migration is a livelihood strategy adopted by young Isan women to seek better lives. Because factory workers earn higher incomes than those working in agriculture, woman migrants can send remittances to their families in rural areas which can be used to renovate houses and buy additional pieces of land as well as daily life necessities. Therefore, rural-to-urban migrations allow these women to fulfill their gender roles as dutiful daughters, good wives and responsible mothers in accordance with social expectations of women’s gender roles in traditional society. -

Arsenite Oxidation and Arsenite Resistance by Bacillus Sp

EnvironmentAsia AvailableAvailable online online at www.tshe.org/EA at www.tshe.org/EA The international journal published by the Thai Society of Higher Education Institutes on Environment EnvironmentAsiaEnvironmentAsia 2 8(1)(2009) (2015) 50-54 9-15 Genotoxicity Assessment of Mercuric Chloride in the Marine Fish Therapon jaruba Arsenite Oxidation and Arsenite Resistance by Bacillus sp. PNKP-S2 Nagarajan Nagarani, Arumugam Kuppusamy Kumaraguru, Velmurugan Janaki Devi Pranee Pattanapipitpaisal, Natanongand Chandrasekaran Yodsing, Rungpha Archana Santhaweesuk Devi and Phitthaya Wamakhan BioremediationCenter Laboratory for Marine Unit, and Faculty Coastal of Studies,Science, SchoolUbon Ratchathani of Energy, University,Environment Ubon and Ratchathani Natural Resources, 34190, Thailand Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai-625021, India Abstract Abstract Arsenic causes human health problems after accumulate in the body for 10-15 years and arsenite [As(III)] is generally regarded as being more mobile and toxic than other oxidation states. In this study, two-hundred and three bacterial strains wereThe isolated aim offrom the groundwaterpresent study and was soil to samplesstandardize collecting and to inassess Ubon the Ratchathani predictive Province, value of theThailand. cytogenetic All strains analysis were byscreened Micronucleus for arsenic (MN) tolerant test in efficiency fish erythrocytes at 1-10 as mM a biomarker of sodium for arsenite. marine environmentalEighteen selected contamination. strains which Micronucleus had the highest frequencyresistance to baseline 10 mM inof erythrocytesAs(III) were further was evaluated studied for in theirand genotoxic As(III)-oxidizing potential activity of a common and growth chemical in enrichment was determined and growth inmedium fish experimentally (EG medium) exposedsupplemented in aquarium with 0.58 under mM controlled of As(III). -

Sub-Area Study and Analysis 5T Sub-Area

Sub-area Study and Analysis 5T Sub-area BDP UNIT THAI NATIONAL MEKONG COMMITTEE DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT OCTOBER 2004 Table of Content Table of Content ............................................................................................................2 Acronyms and abbreviations..........................................................................................3 Map of sub-area 5T........................................................................................................4 Executive summary........................................................................................................5 Introduction....................................................................................................................8 Context and scope of sub-area analysis .........................................................................8 National Overview.........................................................................................................9 Sub-area baseline study................................................................................................14 Development Objectives, plans and policies.......................................................14 Institutional capacity ...........................................................................................16 Socio-economic description and information on resources users .......................17 Inventory of physical features and water resources ............................................18