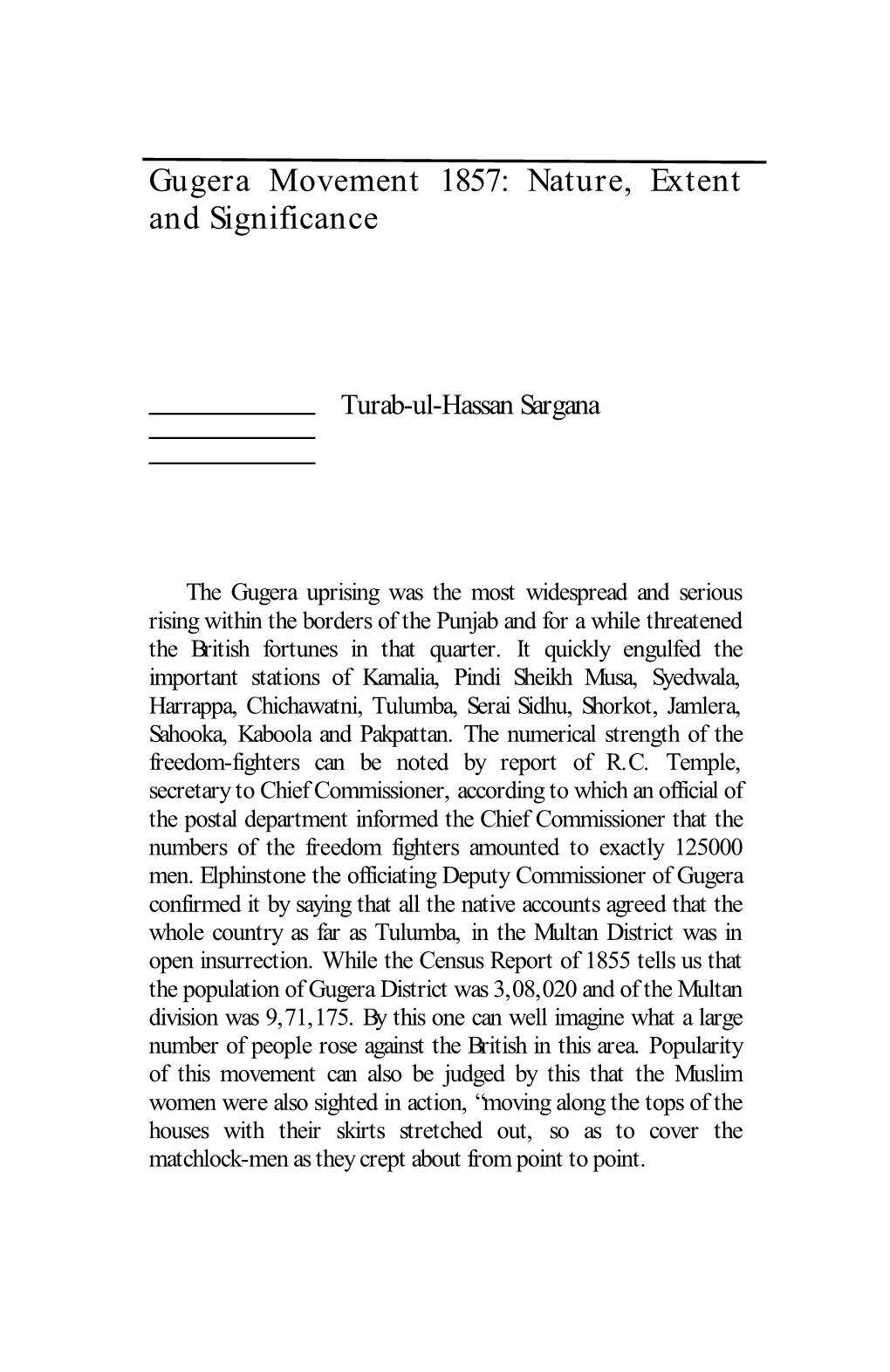

Gugera Movement 1857: Nature, Extent and Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

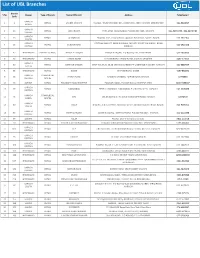

347 ZTBL Branches That Shall Remain Open on Saturday W.E.F 12.09.2020 to 31.12.2020

347 ZTBL Branches that shall remain open on Saturday w.e.f 12.09.2020 to 31.12.2020 Sr. Branch Branch Name Zone Name Location/Address No. Code 1 22304 Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar Kamboh House, Boys Degree Collge Road, Bahawalnagar 2 22353 Bahawalnagar City Bahawalnagar Grain Market, Cantt. Road, Bahawalnagar City 3 22337 Madrassa Bahawalnagar Main Chishtian Road,Madrassa 4 22329 Donga Bonga Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar Road, Donga Bonga 5 22348 Gajyani Bahawalnagar Highway Haroonabad Road, Gajyani 6 22311 Fort Abbas Bahawalnagar Maroot Road, Near Bus Stand, Fortabbas 7 22338 Maroot Bahawalnagar High Way Road, Maroot 8 22344 Khichiwala Bahawalnagar Plot No. 57,Wahlar Road, Khichiwala. 9 22312 Haroonabad Bahawalnagar Goddi Road, Near Educare School, Haroonabad 10 22332 Fakir Wali Bahawalnagar High Way Road, Fakir Wali 11 22310 Minchinabad Bahawalnagar Pakpattan Road, Near AC Office, Minchinabad 12 22330 Ahmedpur Mclood Gunj Bahawalnagar Main Road, General Bus Stand, Ahmedpur Mclood Gunj 13 22343 Chabhyana Bahawalnagar Main Highway Road, Chabhyana 14 22349 Mandi Sadiq Gunj Bahawalnagar Amroka Road, Mandi Sadiq Gunj 15 22305 Chishtian Bahawalnagar High Way Road, (sugar Mill Road), Chishtian 16 22336 Bakhshan Khan Bahawalnagar High Way Chishtian Road, Bakhshan Khan 17 22331 Dahranwala Bahawalnagar Opposite High School for Boys, Dahranwala 18 22301 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur H No.8-A, Dubai Chowk, Ahmedpur East Road, Bahawalpur 19 22323 Noorpur Nauranga Bahawalpur Main Khanqah Road, Near Pull Shahab,Noorpur Nauranga 20 22341 Khanqah Sharif Bahawalpur -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Nankana Sahib

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT NANKANA SAHIB AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENT ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ....................................................... i PREFACE ................................................................................................. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... iv SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ...................................................... vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ............................................................ vii Table 2: Audit observation regarding Financial Management ............. vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ................................................................. vii Table 4: Table of Irregularities Pointed Out....................................... viii Table 5 Cost-Benefit ........................................................................... viii CHAPTER-1 .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 District Government, Nankana Sahib...................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction of Departments ................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ...... 1 1.1.3 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance on MFDAC Audit Paras of Audit Report 2014-15 ..................................... 4 1.1.4 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance with PAC Directives ............................................................................... -

Colonial Transformation in the District of Sheikhupura, 1849-1947

Iram Naseer Ahmad* COLONIAL TRANSFORMATION IN THE DISTRICT OF SHEIKHUPURA, 1849-1947 Abstract This research paper analyses the British colonial transformation in the district of Sheikhupura. The geographical, revenue, judicial and administrative changes have been understood in the sense of establishing a controlled society in the district. This paper sheds light on colonial changes in the district of Sheikhupura under the British raj from 1857 to 1947. The phenomenon of introducing a new administrative and revenue mechanism in Sheikhupura was a project that was not detached from imperialistic ambitions and designs of colonial power in whole of India. The new colonial administrative system, including the reorganization and demarcation of boundaries and setting up centralized administrative machinery particularly a strong revenue, police, and judicial system. Ironically, it was devised to effectively protect the “world monopoly of industrial production” in the British India. It was enforced effectively by a reconstitution of the power structure of the land which meant search for new allies. At the end the article examines the origin of new towns and tehsils in Sheikhupura after the advent of British rule. It observes that British colonialism altered the whole scenario in Sheikhupura which was considered of crucially important for initial colonial control in this district. Keywords: Sheikhupura, British, Imperialism, colonialism The era of British colonialism in the district of Sheikhupura has been divided into three stages. The first stage of colonialism stretches from 1600 to 1757, it deals with the period of monopoly of natural trade and extraction of revenue.1In this stage British traders monopolized the trade with the other European traders as well. -

Smallholder Milk Production in the Punjab of Pakistan and the Evaluation of Potential Interventions

Institute of Animal Production in the Tropics and Subtropics Section Animal Breeding and Husbandry University of Hohenheim Prof. Dr. Christian F. Gall Smallholder milk production in the Punjab of Pakistan and the evaluation of potential interventions Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Agricultural Sciences to the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences by Nils Teufel from Bremen 2007 With support by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the Herzog-Carl-Stiftung Defence of the dissertation: 24/02/2006, University of Hohenheim, 70593 Stuttgart, Germany Examiners: Prof. Dr. C. F. Gall, Prof. Dr. F. Heidhues, Prof. Dr. H.-P. Piepho Acknowledgements During the time it has taken to complete this study, help and support has been provided by a great number of people and institutions. There is no doubt that the study would not have taken place without the initiative and support of Prof. Dr. Christian Gall, my mentor for many years. His insight in livestock production systems and his concern for rural development in addition to his patience, good-will and commitment were fundamental for bringing the study forward to its present state. For all this I would like to express my deep gratitude and wish him many more years of enthusiastic activity. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Franz Heidhues and Prof. Dr. Hans-Peter Piepho for agreeing to participate in the evaluation process of this study. The economic framework of this study was formed and guided by Prof. Martin Upton and Prof. Dr. Tahir Rehman during a 6-month visit as guest scientist to The University of Reading. -

Nankana Sahib Eligible

Page 1 of 6 APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR RECRUITMENT AS SANITARY WORKER IN PUNJAB CONSTABULARY TILL 07-04-2021 FROM DISTRICT NANKANA SAHIB ELIGIBLE Form Name with Address as per CNIC District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. # Edu: Remarks No. parentage with CNIC No. Domicile Birth 07-04-2021 57% 15 % 05 % 03 % Son 20 % Fit Kot Hussain p/o same, Muhammad Farooq s/o 1 116 Nankana Sahib 35501-0491247- Nankana sahib 01/10/1995 F.sc 25Y,6M,6D yes Fit Sher Muhammad 9 Bahru Chak No.18/RB, p/o Aynal Masih s/o 2 123 same Tehsil Shah kot, Nankana Nankana sahib 21/02/1997 Illiterate 24Y,1M,17D yes Fit Amanawail Masih Sahib 35502-0238583-3 Mohallah Bilal Nagar, Ghulam Dastgeer s/o 3 151 Morrkhanda, Nankana Sahib Nankana sahib 15/09/1997 F.A 23Y,6M,23D yes Fit Manzoor Ahmed 35202-5972478-1 Tailan, p/o Nankana Sahib, Asif Masih s/o Botta 4 153 Nankana Sahib 35501-0215904- Nankana sahib 12/02/1988 Middle 33Y,1M,26D yes Fit Masih 9 Thatha Roop chand p/o Husnain Abbas Shah s/o 5 174 Syedanwala, Nankana Sahib Nankana sahib 25/03/1998 Middle 23Y,0M,13D yes Fit Riaz Hussain 35501-0550856-3 Chak No.50/RB, Umarpur Qaisar Masih s/o Shahbaz Tawana, Tehsil Shahkot, 6 284 Nankana sahib 02/08/1999 Matric 21Y,8M,5D yes Fit Masih Nankana Sahib 35502-0242224- 1 Ward No.3, Mohallah Purana Sabika Shafaqat w/o Asif 7 292 Chahor, Sangla Hill, Nankana Nankana sahib 01/01/1988 Illiterate 33Y,3M,6D yes Fit Masih Sahib 35503-0197717-0 P/o Murr Khanda, Choukhian Ahmed Nawaz s/o 8 311 wala, Nankana Sahib 35501- Nankana sahib 03/04/1996 F.A 25Y,0M,4D yes Fit Mansab Ali 0351662-9 Madina Colony warburton, Muhammad Nawaz s/o 9 337 Nankana Sahib 35402-2454358- Nankana sahib 05/05/1978 Middle 42Y,11M,2D yes Fit Muhammad Ismeel 1 Page 2 of 6 Form Name with Address as per CNIC District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. -

II Pakistani Schedule Banks Branches As on 31 December 2010

Appendix - II Pakistani Schedule Banks Branches As on 31st December 2010 Allied Bank Ltd. -Noor Hayat Colony -Mohar Sharif Road (806) Bheli Bhattar (A.K.) Chitral Abbaspur 251 RB Bandla Bhiria Chungpur (A.K.) Dadu Abbottabad (4) Burewala (2) -Bara Towers, Jinnahabad -Grain Market Dadyal (A.K) (2) -Pineview Road -Housing Scheme -College Road -Supply Bazar -Samahni Ratta Cross -The Mall Chak Jhumra Chak Naurang Daharki Adda Johal Chak No. 111 P Danna (A.K.) Adda Nandipur Rasoolpur Chak No. 122/JB Nurpur Danyor Bhal Chak No. 142/P Bangla Darband Adda Pansra Manthar Dargai Adda Sarai Mochiwal Chak No. 220 RB Darhal Gaggan Adda Thikriwala Chak No. 272 HR Fortabbas Daroo Jabagai Kombar Alipur Chak No. 280/JB (Dawakhri) Ahmed Pur East Chak No. 34/TDA Daska (2) Akalgarh (A.K) Chak No. 354 -Kutchery road Arifwala Chak No. 44/N.B. -Village budha Attock (Campbellpur) Chak No. 509 GB Bagh (A.K) Chak No. 61 RB Daurandi (A.K.) Bahawalnagar Chak No. 76 RB Deenpur Chak No. 80 SB Deh Uddhi Bahawalpur (5) Chak No. 88/10 R Dinga Chak No. 89/6-R -Com. Area Sattelite Town Chakothi -Dubai Chowk Dera Ghazi Khan (2) -Farid Gate -Azmat Road -Ghalla Mandi Chakwal (3) -Model Town -Settelite Town -Mohra Chinna -Sabzimandi Dera Ismail Khan (3) Bakhar Jamali Mori Talu -Talagang Road -Circular Road Bhawanj -Commissionery Bazar Balagarhi Chaman -Faqirani Gate (Muryali) Balakot Chaprar Baldher Charsadda Dhamke (Faisalabad) Bucheke Chaskswari (A.K) Dhamke (Sheikhupura) Chattar (A.K) Dhangar Bala (A.K) Chhatro (A.K.) Bannu (2) Dheed Wal -Chai Bazar (Ghalla Mandi) Dhudial (Punjab) -Preedy Gate Chichawatni (2) Dina -College Road Dipalpur Barja Jandala (A.K) -Railway Road Dir Batkhela Dunyapur Behari Agla Mohra (A.K.) Chilas Ellahabad Bewal Eminabad More Bhagowal Chiniot (2) Bhakkar -Muslim Bazar (Main) Faisalabad (20) Bhaleki (Phularwan Chowk) -Sargodha Road -Akbarabad -Chibban Road Bhalwal (2) Chishtian (2) -Factory Area -Grain Market -Grain Market 335 -Ghulam Muhammad Abad -Grand Trunk Road -Bara Kahu Colony -Rehman Saheed Road -Blue Area -Gole Cloth Market -Shah Daula Road. -

December 16-31, 2019 January 01-15, 2021

December 16-31, 2019 January 01-15, 2021 SeSe 1 Table of Contents 1: January 01, 2021………………………………….……………………….…03 2: January 02, 2021………………………………….……………………….....12 3: January 03, 2021…………………………………………………………......15 4: January 04, 2021………………………………………………...…................20 5: January 05, 2021………………………………………………..…..........….. 27 6: January 06, 2021………………………………………………………….…..28 7: January 07, 2021………………………………………………………………34 8: January 08, 2021……………………………………….………………….......41 9: January 09, 2021……………………………………………...……………….43 10: January 10, 2021…………………………………………………….............46 11: January 11, 2021………………………………………………………….….48 12: January 12, 2021……………………………………………………………. 54 13: January 13, 2021…………………………………………………………..…56 14: January 14, 2021………………………………………………………..….....67 15: January 15, 2021……………………………………………….………..….. 70 Data collected and compiled by Rabeeha Safdar, Maroosha Sarfraz and Zohaib Sultan Disclaimer: PICS reproduce the original text, facts and figures as appear in the newspapers and is not responsible for its accuracy. 2 January 01, 2021 Business Recorder China to provide over 1m doses of the Covid-19 vaccine to Pakistan ISLAMABAD: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Thursday assured China‘s commitment to provide over one million doses of the Covid-19 vaccine to Pakistan for emergency use. The Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister stated this during a telephonic conversation with Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi. According to a statement of the Foreign Office, during conversation, Foreign Minister Qureshi emphasized that China had made remarkable achievement in developing Covid-19 vaccines, adding that the phase-III clinical trials of China‘s vaccine were progressing well in Pakistan. He maintained that the government had approved Sinopharm vaccine for emergency use in Pakistan, and expressed hope for its early availability from China. ―Foreign Minister Wang Yi assured that China would work to provide over one million doses of the vaccine to Pakistan for emergency use,‖ the statement added. -

Psdp 2009-2010

WATER & POWER DIVISION (WATER SECTOR) (Million Rupees) Sl. Name, Location & Status of the Estimated Cost Expenditure Throw- Allocation for 2009-10 No Scheme Total Foreign upto June forward as on Foreign Rupee Total Loan 2009 01-7-09 Loan 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 On-going Schemes 1 Raising of Mangla Dam including 101384.330 0.000 62204.003 39180.327 0.000 12000.000 12000.000 resettlement 2 Mirani Dam 5811.000 0.000 5247.260 563.740 0.000 313.740 313.740 3 Sabakzai Dam 2005.545 0.000 1488.990 516.555 0.000 280.000 280.000 4 Satpara Multipurpose Dam 4805.975 195.786 2193.998 2611.977 0.000 50.000 50.000 5 Gomal Zam Dam 12829.000 4964.000 2951.922 9877.078 0.000 2000.000 2000.000 6 Greater Thal Canal (Phase - I) 30467.109 0.000 7176.962 23290.147 0.000 1000.000 1000.000 7 Kachhi Canal (Phase - I) 31204.000 0.000 18625.016 12578.984 0.000 4000.000 4000.000 8 Rainee Canal (Phase - I) 18862.000 0.000 5051.287 13810.713 0.000 2000.000 2000.000 9 Lower Indus Right Bank Irrigation & 14707.143 0.000 10819.677 3887.466 0.000 1500.000 1500.000 Drainage, Sindh 10 Balochistan Effluent Disposal into RBOD. 6535.970 0.000 2548.353 3987.617 0.000 800.000 800.000 (RBOD-III) 11 Feasibility Studies of Dams (Naulong, 378.468 0.000 191.485 186.983 0.000 60.000 60.000 Hingol), Balochistan 12 Land and Water Monitoring / Evaluation 427.000 0.000 0.000 427.000 0.000 40.000 40.000 of Indus Plains (SMO) 13 Construction of IRSA Office building, 38.250 0.000 28.250 10.000 0.000 10.000 10.000 Islamabad 14 Revamping/Rehabilitation of Irrigation & 16796.000 0.000 8850.000 7946.000 -

To Download UBL Branch List

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI. -

LIST of Mpas

04 October 2021 PPRROOVVIINNCCIIAALL AASSSSEEMMBBLLYY OOFF TTHHEE PPUUNNJJAABB LLIISSTT OOFF MMPPAAss www.pap.gov.pk E-mail: [email protected] Prepared by LEGISLATION SECTION 042-99204251 1 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PUNJAB Assembly Exchange-PABX: 042-99200335-47 MPAs Hostel Exchange: 042-99200590-99 Pipals House Exchange: 042-99212761-70 OFFICERS OF THE HOUSE SPEAKER MR PARVEZ ELAHI House No.30-C, Zahoor Elahi Road, Gulberg-II, Lahore 042-99200311 (Off), 042-99200312 (Fax) 042-35712666, 042-35762666 (Res) DEPUTY SPEAKER SARDAR DOST MUHAMMAD MAZARI 2-Upper Mall, Lahore 042-99200313 (Off), 042-99200314 (Fax) 042-99201280, 042-99203655 (Res) 2 SECRETARY MR MUHAMMAD KHAN BHATTI 1-B, Club Road, GOR-I, Lahore 042-99200321, 042-99204244 (Off), 042-99200330 (Fax) 0341-8445500 DIRECTOR GENERAL (PA&R) MR INAYAT ULLAH LAK 84-B, GOR-II, Bahawalpur House, Mozang, Lahore 042-99200332 (Off), 042-35243050 (Res) 0300-4407510 DEPUTY SECRETARY (LEGISLATION) MR ALI HUSSNAIN BHALLI 126 Khushnuma GOR-IV, Model Town Extension, Lahore 042-99200323 (Off), 0321-6121007 3 CHIEF MINISTER PP-286 (PTI) Mr Usman Ahmed Khan Buzdar Chief Minister 8 Club Road, GOR-I, Lahore 042-99203228, 042-99203229 SENIOR MINISTER PP-158 (PTI) Mr Abdul Aleem Khan Minister for Food 55-C-II, Gulberg-III, Lahore 042-99204357 042-99203218 (Off), 042-99204357 (Fax), 0345-8444101 MINISTERS PP-1 (PTI) PP-4 (PTI) Syed Yawar Abbas Bukhari Malik Muhammad Anwar Minister for Social Welfare & Bait ul Maal Minister for Revenue PO Kamra, Attock (a) 108- New Minister Block, 0300-8505254 Punjab Civil Secretariat, Lahore (b) Tehsil Pindigheb, District Attock 042-99214745, 042-99214746 (Off), 0300-8428435 4 PP-14 (PTI) PP-21 (PTI) Mr Muhammad Basharat Raja Mr Yasir Humayun Minister for Law & Parliamentary Affairs, Minister for Higher Education Cooperatives (Addl. -

Annual Policing Plan for the Year 2018-19 District

ANNUAL POLICING PLAN FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 DISTRICT NANKANA SAHIB District Police Officer, Nankana Sahib. 2 PREFACE According to Article 32(4) of Police Order 2002, Head of the District Police shall prepare Annual Policing Plan. The Policing Plan sets out our strategic objectives for the year 2018-19. One of the guiding principles of the plan is that police will continue to improve its performance through intelligence-led operations and high visibility patrolling. Managing crime and ensuring safety to the public are part of our core business. This year‟s plan identifies a number of key actions including targeting organized crime as well as renewed focus on crimes against the person and property. The policing plan also outlines Punjab Police priorities in the key areas of enhancing partnerships with the community and other agencies with a view to identify and solve problems together, reduce anti-social behavior and provide security to all society. Immense increase in population, proliferation of weapons, maintenance of law and order, security of religious places and other assignment of the similar nature makes our targets difficult. This year we plan to re-divert our greater energies & resources for crime prevention and detection to ensure safety of the public at large particularly during Muharram. Moreover, due to the presence of "Sikh" holy places, we reiterate to concentrate more on their security to make their visit safe and memorable to Nankana Sahib, in order to boost the image of Pakistan. The Policing plan summarizes Establishment of "Khidmat Markaz" facilitation Centre and other IT related initiatives which leads to modern policing to promote and improve the perception about the Punjab Police Department within the general public. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Nankana Sahib Audit

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT NANKANA SAHIB AUDIT YEAR 2017-18 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENT ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ..................................................... i PREFACE .............................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................... iii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ...................................................... vi Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ........................................................... vi Table 2: Audit observation regarding Financial Management ............. vi Table 3: Outcome Statistics ............................................................... vii Table 4: Table of Irregularities Pointed Out ..................................... viii Table 5 Cost-Benefit ......................................................................... viii CHAPTER-1 .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 District Government, Nankana Sahib..................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction of Departments .................................................. 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ...... 1 1.1.3 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance on MFDAC Audit Paras of Audit Report 2016-17 .................................... 3 1.1.4 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance with PAC Directives .............................................................................. 3