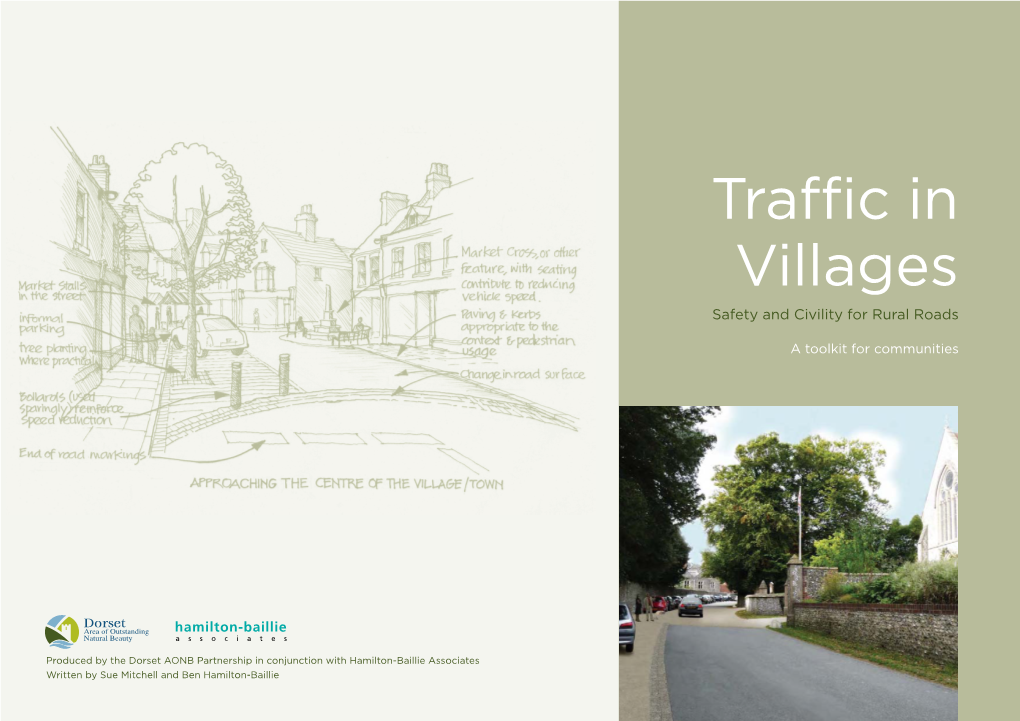

Traffic in Villages Safety and Civility for Rural Roads 1 a Toolkit for Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Ward, S. (2017) 'Colin Buchanan's American Journey', Town Planning Review, 88 (2), pp. 201-231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2017.13 This document is the authors’ Accepted Manuscript. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available from RADAR: https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/72ee92f0-fe9a-49fd-9b1d-7f86d6c61059/1/ Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners unless otherwise waved in a license stated or linked to above. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Colin Buchanan’s American Journey Stephen V. Ward School of the Built Environment Oxford Brookes University Headington Oxford OX3 OBP, UK [email protected] 1 Colin Buchanan’s American Journey Introduction In Autumn 1962, the British planner, Colin Buchanan, made an extensive eight-week tour of the United States. His purpose was professional and official, part of a major British government study to find appropriate planning responses to the long term problems of urban motor traffic. Buchanan’s intention was to learn and draw lessons from American experiences that could be applied to Britain, then becoming a mass motorised society. -

Accessibility in Cities: Transport and Urban Form

NCE Cities – Paper 03 ACCESSIBILITY IN CITIES: TRANSPORT AND URBAN FORM Lead Authors: Philipp Rode and Graham Floater Contributing Authors: Nikolas Thomopoulos, James Docherty, Peter Schwinger, Anjali Mahendra, Wanli Fang LSE Cities Research Team: Bruno Friedel, Alexandra Gomes, Catarina Heeckt, Roxana Slavcheva The New Climate Economy Page CONTENTS The New Climate Economy (NCE) is the flagship project of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. It was established by seven countries, Colombia, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Norway, South Korea, Sweden and 1 INTRODUCTION 03 the United Kingdom, as an independent initiative to examine how countries can achieve economic growth while dealing with the risks posed by climate change. The NCE Cities Research Programme is led by LSE Cities at the 2 ACCESSIBILITY IN CITIES AND 04 London School of Economics. The programme includes a consortium of IMPLICATIONS FOR researchers from the Stockholm Environment Institute, the ESRC Centre CARBON EMISSIONS for Climate Change Economics and Policy, the World Resources Institute, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, and Oxford Economics. The NCE Cities Research Programme is directed by Graham Floater and Philipp Rode. 3 ASSESSMENT 11 4 PATTERNS, TRENDS AND 19 ABSTRACT TIPPING POINTS This paper focusses on one central aspect of urban 5 ACCESSIBILITY THROUGH 32 development: transport and urban form and how the two COMPACT CITIES shape the provision of access to people, goods and services, AND SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT and information in cities. The more efficient this access, the greater the economic benefits through economies of scale, agglomeration effects and networking advantages. This 6 CONCLUSIONS 40 paper discusses how different urban accessibility pathways impact directly on other measures of human development BIBLIOGRAPHY 42 and environmental sustainability. -

The History of Transport Systems in the UK

The history of transport systems in the UK Future of Mobility: Evidence Review Foresight, Government Office for Science The history of transport systems in the UK Professor Simon Gunn Centre for Urban History, University of Leicester December 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr Aaron Andrews for his help with the research for this review, especially for creating the graphs, and Georgina Lockton for editing. The review has benefited from the input of an Advisory Group consisting of Professor Colin Divall (University of York); Professor Gordon Pirie (University of Cape Town); Professor Colin Pooley (Lancaster University); Professor Geoff Vigar (University of Newcastle). I thank them all for taking time to read the review at short notice and enabling me to draw on their specialist expertise. Any errors remaining are, of course, mine. This review has been commissioned as part of the UK government’s Foresight Future of Mobility project. The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent those of any government or organisation. This document is not a statement of government policy. This report has an information cut-off date of February 2018. The history of transport systems in the UK Executive summary The purpose of this review is to summarise the major changes affecting transport systems in the UK over the last 100 years. It is designed to enable the Foresight team to bring relevant historical knowledge to bear on the future of transport and mobility. The review analyses four aspects of transport and mobility across the twentieth century. The first section identifies significant points of change in the main transport modes. -

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods Residents Survey

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods Residents' Survey Report January 2021 Tracy Logan, Rob McPhedran, Amy Young, Emily King Contents Background and methodology 3 Background 3 Survey and sample methodology 6 A note on survey timing 6 Weighting 7 Notes on analysis 8 Area and LSOA subgroups 8 Social Grade definition 9 Business owners 9 Respondents with mobility issues 9 Mode of transport sub-group definitions 10 Executive Summary 11 Views on government action in local neighbourhoods 11 Support for the reduction of road traffic and the reallocation of space for walking and cycling 11 Perceived problems in local areas 12 Awareness of and support for local LTN 12 Support for wider implementation of LTNs across England 13 Perceived impact of local LTN 14 Views on government action in local neighbourhoods 15 Support for reduction of road traffic 18 Support for reallocation of road space for walking and cycling 21 Perceived problems in local areas 24 Awareness of and support for local LTN 27 Support for local LTN 28 Impact of local LTN 31 Frequency of transport use and visits to local businesses 38 Support for implementing LTNs more widely 42 Business Owner residents 44 Appendix 48 Questionnaire – online version 48 © Kantar 2020 1 Background and methodology Background In May 2020, the Secretary of State for Transport announced the Emergency Active Travel Fund, which included funding allocations for emergency active travel schemes for local authorities. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) offer a cost-effective way of delivering safe streets for walking and cycling. LTNs work by minimising through-traffic from using residential neighbourhoods to avoid main roads, while still retaining local access for residents, visitors and emergency vehicles. -

Walking in the Modern City: Pedestrian Experiences of Post-War Birmingham

Centre for Environment and Society Research Working Paper series no. 23 Walking in the Modern city: pedestrian experiences of post-war Birmingham David Adams Walking in the Modern city: pedestrian experiences of post- war Birmingham David Adams Lecturer in Planning Birmingham School of the Built Environment, Birmingham City University Working Paper Series, no. 22 2013 ISBN 978-1-904839-73-6 © Author, 2013 Published by Birmingham City University Centre for Environment and Society Research Faculty of Technology, Engineering and the Environment City Centre campus, Millennium Point, Curzon Street, Birmingham, B4 7XG, UK iii CONTENTS Abstract iv Introduction 1 Post-war Birmingham and pedestrian movement 2 Research context and methods 5 Experiences of walking in the reconstructed city 6 Pedestrian mobilities and vehicular traffic 6 Spaces for leisured activities 8 Legacies of the past, and altered routines 10 Conclusion 12 References 14 Illustrations Figure 1 Smallbrook Ringway under construction c. 1960 3 Figure 2. Aerial perspective of the Bull Ring, c. 1964 9 Figure 3 The new Bullring 11 iv Abstract Whilst the act of walking has been a central focus of many authors in their attempts to comprehend the effects of modernisation processes on everyday life in the city, there has been little empirical exploration of the relationship between how pedestrian practices were imagined and proposed by post-war planners / architects and how they were experienced ‘on the ground’ by local inhabitants. Drawing on research conducted in Birmingham – a city radically reconstructed with vehicular rather than pedestrian movement in mind – this paper uses a series of oral testimonies with local residents to highlight their different experiences of living with the reality of a city designed around the needs of motorised traffic. -

Urban Transportation Problem

THE URBAN TRANSPORTATION PROBLEM GILBERT PAUL VERBITt TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 369 II. THREE VIEWS OF THE PROBLEM ................................ 372 A. The TransportationDisadvantaged ........................ 372 1. The Young .................................................... 373 2. The Elderly ................................................... 373 3. The Handicapped ........................................ 377 4." The Poor ....................................................... 378 5. Summary ....................................................... 388 B. Congestion ............................................................388 C. The Automobile Commuter .................................... 390 III. SYSTEM COSTS OF AUTOMOBILE COMMUTING ............ 392 A. The Automobile as an Energy Water ..................... 392 B. The Automobile as a Polluter ................................ 394 C. The Automobile as a Tortfeasor ............................. 397 D. The Automobile as a Space Waster ........................ 398 IV. THE URBAN MASS TRANSPORTATION ACT OF 1964 .. 401 A. The Act's Preferencefor Rail Rapid Transit .......... 401 B. The Basis for the Act's Preference for Rail Rapid Transit ................................................................. 412 1. Potential Benefits Examined ........................ 413 a. Cost ............................................................ 413 b. Speed .......................................................... 414 c. Labor -

Traffic Calming, Auto-Restricted Zones and Other Traffic Management Techniques-Their Effects on Bicycling and Pedestrians

Publication No. FHWA-PD-93-028 Case Study No. 19 Traffic Calming, Auto-Restricted Zones and Other Traffic Management Techniques- Their Effects on Bicycling and Pedestrians National Bicycling And Walking Study U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration National Bicycling and Walking Study FHWA Case Study No. 19 Traffic Calming, Auto-Restricted Zones and Other Traffic Management Techniques---Their Effects on Bicycling and Pedestrians Submitted to: Federal Highway Administration 400 Seventh Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20590 January 1994 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary v I. Introduction ................................................................................. 1 II. The History and Development of Traffic Calming ......................... 3 1. Pedestrianization..................................................................... 4 2. Woonerven............................................................................. 7 3. Verkehrsberuhigung ..............................................................12 4. Traffic Calming in Denmark...................................................19 5. Traffic Calming in Japan ........................................................19 6. Other Traffic-Reduction Strategies ........................................20 7. Summary ...............................................................................23 III. Traffic Calming in the United States ............................................25 Types of United States Traffic-Calming Techniques.....................25 -

Less Traffic Where People Live: How Local Transport Schemes Can Help Cut Traffic

Less Traffic Where People Live: How local transport schemes can help cut traffic Built Environment Lynn Sloman Fellowship Less Traffic where People Live: How local transport schemes can help cut traffic Acknowledgements This research was generously supported by a Built Environment Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. Further information about the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 is available at http://www.royalcommission1851.org.uk Valuable research facilities were provided through a Visiting Fellowship at University of Westminster Transport Studies Group (http://www.wmin.ac.uk/transport/). Much advice and information was contributed by Transport 2000 Trust: http://www.transport2000.org.uk. With special thanks for intellectual and moral support to Alan Baxter, Sally Cairns, Stephen Coley, Peter Jones, Stephen Joseph, Colin Murray, Carey Newson, Malcolm Shirley, Ian Taylor, Sophie Tyler and Sarah Wixey. © Lynn Sloman, Transport for Quality of Life April 2003 Further copies of this report are available as a PDF file from: Transport for Quality of Life, 13 Maengwyn Street, Machynlleth SY20 8EB [email protected] ort for Quality of Life Transport for Quality of Life 3 Foreword Bumper-to-bumper traffic is one of the biggest problems we face in towns and cities. Opinion polls show that people are more and more concerned about the noise, pollution, danger and congestion caused by growing car use. Policy-makers say they aim to reduce congestion, but without trying to cut traffic. But it is simply not credible that congestion will fall, and continue to fall, while traffic volumes go up. Road widening and bigger junctions may ease traffic jams in the very short term, but in the long term they will contribute to yet more car-dependent lifestyles, more traffic and more congestion. -

Effective Road and Traffic Management: Memoranda Received

This bundle: 55 & 56 Effective road and traffic management: Memoranda Received No. Author 28 National Grid plc 01 Leornard Wells 28a Supplementary from National Grid plc 02 David Nelsey 29 National Joint Utilities Group (NJUG) 03 English Heritage 29a Supplementary from NJUG 04 Ken Todd 30 Stagecoach Group plc 05 Urban Traffic Management & Control (UTMC) 31 Road Haulage Association (RHA) 05a Supplementary from UTMC and the IHE 32 Capita Symonds 06 Intelligent Transport Systems (UK) 33 Donald Bowler 06a Supplementary from ITS (UK) 34 Stephen Plowden 07 Transport Research Laboratory (TRL) 35 City of London Corporation 08 David Metz 36 Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport (CILT) 09 London TravelWatch 36a Supplementary from CILT 10 Passenger Focus 37 Jonathan Smith 11 Surrey County Council 38 Tony Wyer 12 ADEPT 39 Institution of Engineering and Technology 13 Cambridge Cycling Campaign 40 Transport Planning Society 14 Institute of Highway Engineers (IHE) 41 AA 15 Martin Cassini 42 Joint Authorities Group (UK) 16 Passenger Transport Executive Group (pteg) 43 CTC, the national cyclists' organisation 16a Supplementary from pteg 44 Halcrow 17 RAC Foundation 45 Chris Leithead 18 Campaign for Better Transport 46 Sustrans 19 liftshare 47 Freight Transport Association (FTA) 20 MIRA 48 Living Streets 21 Local Government Technical Advisers Group 49 Motorcycle Action Group (UK) 22 Chartered Institute of Highways and Transport 50 Cadence Driver Development 23 Network Rail 51 Motor Cycle Industry Association (MCI) 24 Kapsch TrafficCom 52 Greater London Authority 25 Department for Transport 53 Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) 26 Michael Coles 54 London Councils 26a Further evidence from Michael Coles 55 Cycle Sheffield 27 Green Light Group (GLG) 56 Nottinghamshire County Council Written evidence from Leonard Wells (ETM 01) I am a 70 year old pensioner. -

Transit System As a Project of Urbanity

Milos STIPCIC QRU 7/ 121 TRANSIT SYSTEM AS A PROJECT OF URBANITY Milos STIPCIC Up to which point a transit system, a primarily utilitarian element of the Transit system - Synergy of the synergies city, could become a positive constituent of urban context, giving it a new significance and an additional value? In the last few decades, there is a rela- Up to which point a transit system, primarily utilitarian element of the city, tively new and increasing phenomenon in urbanism which is to put more could become an affirmative constituent of urban context, giving it a new effort into the integration of transit system and its surrounding. In different significance and an additional value? regions of the world, multidisciplinary teams of planners are working on many-sided urban projects along the transit routes in order to establish a Is it possible to exceed usual functional requirements and treat a transit sys- stronger dialog between mobility and the built environment, regardless the tem as a multidisciplinary project of urbanity? transport mode, size of city or urban context. The objective of this discussion How these general ideas could be adapted to different urban and economic is to give a general overview of this phenomenon and to evaluate some com- contexts? mon ideas or outcomes. Being part of a wider investigation, this short discussion has as the objective Keywords: Public space, Urban mobility, Urban quality to analyze a relatively new phenomena of treating a transport systems as a generator of urbanity, integrating them into the context or adapting the surroundings to their presence. -

Streetscape Urban Design Group Urban

and MAKING STREETS PEOPLE ENJOY Summer 2018 Urban Design Group Journal 147URBAN ISSN 1750 712X DESIGN STREETSCAPE Clapham Old Town Public Realm Brighton North Street Public Realm WINNER: NLA Awards 2015 ‘Best Public Space’; and HIGHLY COMMENDED at the Landscape Institute Awards 2017, WINNER: London Planning Awards 2015 ‘Best New Public Space’ ‘Adding Value through Landscape’. Venn Street Public Realm Glasgow City Centre Avenues WINNER: London Transport Awards 2015 ‘Excellence in Walking’; UM is the lead designer for this ambitious project, making the and HIGHLY COMMENDED at the RTPI Awards 2015. city centre’s main streets better for walking, cycling, + city life. We specialise in research, planning, strategy and design for streets, and our inter-disciplinary team has all the skills necessary to work creatively and effectively in the most complex and challenging of urban environments. Exmouth House 3 - 11 Pine Street We understand the real social, cultural and London EC1R 0JH economic value of streets and spaces, and always @UM_Streets URBAN strive to make cities and towns healthier, more +44 (0)20 3567 0710 [email protected] DESIGN successful, and more enjoyable. www.urbanmovement.co.uk GROUP URBAN DESIGN UDG_Streets_v2.indd 1 06/04/2018 16:37 GROUP NewsUDG NEWS By my current counting, Canary Wharf is going through its third rebuilding in some 30 years, and probably its 30th masterplan. I’m also pretty sure that someone is already thinking that the pointy bit at the top of the Shard is a waste of valuable real estate, and is drafting plans for something more ambitious. I digress. -

Motoring Towards 2050 Established to Promote the Environmental, Economic, Mobility and Safety Issues Relating to Use of Motor Vehicles

The Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Limited is a charity 2050 Motoring towards established to promote the environmental, economic, mobility and safety issues relating to use of motor vehicles. Motoring towards 2050 RAC Foundation 89-91 Pall Mall London SW1Y 5HS Tel: 020 7747 3445 www.racfoundation.org Registered Charity No. 1002705 RAC Foundation The Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Limited is a charity established to promote the environmental, economic, mobility and safety issues relating to use of motor vehicles. RAC Foundation 89-91 Pall Mall London SW1Y 5HS Telephone 020 7747 3445 www.racfoundation.org Registered Charity No. 1002705 May 2002 © Copyright RAC Foundation for Motoring Designed by Price £295 Printed by Moore Motoring towards 2050 an independent inquiry RAC Foundation for Motoring Motoring towards 2050 1 Report steering committee Sir Christopher Foster, Chairman. John Bates, consultant economist. Bill Billington, highways consultant. David Holmes, formerly in senior positions in the Department of Transport and with British Airways. Richard Ide, formerly Chief Executive of Volkswagen Group UK. David Leibling, formerly with Lex and author of the Lex (now RAC) Report on Motoring. Professor Peter Mackie, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds. Richard Mills, Secretary General, National Society for Clean Air and Environmental Protection. Sir Nick Monck, formerly Permanent Secretary, Department of Employment, and second Permanent Secretary, HM Treasury. Professor Chris Nwagboso, Professor of Integrated Transport and Head of the Transport and Automotive Systems Research Centre, Wolverhampton University. Professor Tony Ridley, Professor of Transport Engineering, Imperial College. Robert Upton, Secretary General, Royal Town Planning Institute. Joan Williamson, researcher.