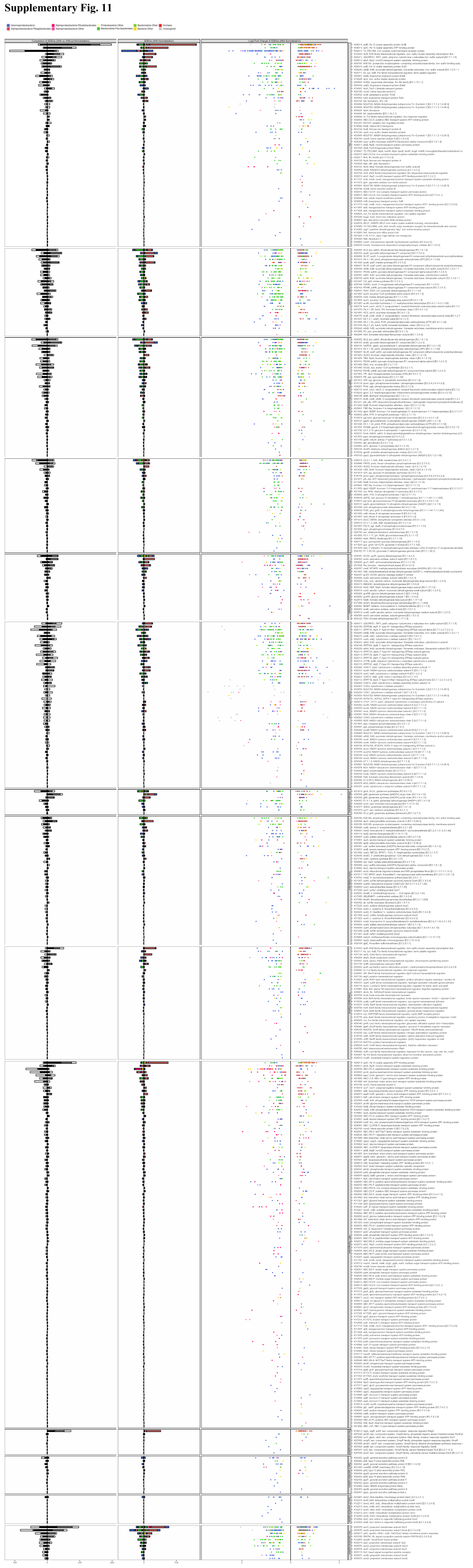

Supplementary Fig. 11.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sulfite Dehydrogenases in Organotrophic Bacteria : Enzymes

Sulfite dehydrogenases in organotrophic bacteria: enzymes, genes and regulation. Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Universität Konstanz Fachbereich Biologie vorgelegt von Sabine Lehmann Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 10. April 2013 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Schink 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. Andrew W. B. Johnston So eine Arbeit wird eigentlich nie fertig, man muss sie für fertig erklären, wenn man nach Zeit und Umständen das möglichste getan hat. (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italienische Reise, 1787) DANKSAGUNG An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich herzlich bei folgenden Personen bedanken: . Prof. Dr. Alasdair M. Cook (Universität Konstanz, Deutschland), der mir dieses Thema und seine Laboratorien zur Verfügung stellte, . Prof. Dr. Bernhard Schink (Universität Konstanz, Deutschland), für seine spontane und engagierte Übernahme der Betreuung, . Prof. Dr. Andrew W. B. Johnston (University of East Anglia, UK), für seine herzliche und bereitwillige Aufnahme in seiner Arbeitsgruppe, seiner engagierten Unter- stützung, sowie für die Übernahme des Koreferates, . Prof. Dr. Frithjof C. Küpper (University of Aberdeen, UK), für seine große Hilfsbereitschaft bei der vorliegenden Arbeit und geplanter Manuskripte, als auch für die mentale Unterstützung während der letzten Jahre! Desweiteren möchte ich herzlichst Dr. David Schleheck für die Übernahme des Koreferates der mündlichen Prüfung sowie Prof. Dr. Alexander Bürkle, für die Übernahme des Prüfungsvorsitzes sowie für seine vielen hilfreichen Ratschläge danken! Ein herzliches Dankeschön geht an alle beteiligten Arbeitsgruppen der Universität Konstanz, der UEA und des SAMS, ganz besonders möchte ich dabei folgenden Personen danken: . Dr. David Schleheck und Karin Denger, für die kritische Durchsicht dieser Arbeit, der durch und durch sehr engagierten Hilfsbereitschaft bei Problemen, den zahlreichen wissenschaftlichen Diskussionen und für die aufbauenden Worte, . -

Analysis of the Impact of Silver Ions on Creatine Amidinohydrolase

ActaBIOMATERIALIA Acta Biomaterialia 1 (2005) 183–191 www.actamat-journals.com A stable three enzyme creatinine biosensor. 2. Analysis of the impact of silver ions on creatine amidinohydrolase Jason A. Berberich b,1, Lee Wei Yang a, Ivet Bahar a, Alan J. Russell b,* a Center for Computational Biology & Bioinformatics and Department of Molecular Genetics & Biochemistry, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA b Department of Surgery, McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15219, USA Received 11 October 2004; received in revised form 26 November 2004; accepted 28 November 2004 Abstract The enzyme creatine amidinohydrolase is a clinically important enzyme used in the determination of creatinine in blood and urine. Continuous use biosensors are becoming more important in the clinical setting; however, long-use creatinine biosensors have not been commercialized due to the complexity of the three-enzyme creatinine biosensor and the lack of stability of its components. This paper, the second in a series of three, describes the immobilization and stabilization of creatine amidinohydrolase. Creatine amidinohydrolase modified with poly(ethylene glycol) activated with isocyanate retains significant activity after modification. The enzyme was successfully immobilized into hydrophilic polyurethanes using a reactive prepolymer strategy. The immobilized enzyme retained significant activity over a 30 day period at 37 °C and was irreversibly immobilized into the polymer. Despite being stabilized in the polymer, the enzyme remained highly sensitive to silver ions which were released from the amperometric electrodes. Computational analysis of the structure of the protein using the Gaussian network model suggests that the silver ions bind tightly to a cysteine residue preventing normal enzyme dynamics and catalysis. -

Protein Identities in Evs Isolated from U87-MG GBM Cells As Determined by NG LC-MS/MS

Protein identities in EVs isolated from U87-MG GBM cells as determined by NG LC-MS/MS. No. Accession Description Σ Coverage Σ# Proteins Σ# Unique Peptides Σ# Peptides Σ# PSMs # AAs MW [kDa] calc. pI 1 A8MS94 Putative golgin subfamily A member 2-like protein 5 OS=Homo sapiens PE=5 SV=2 - [GG2L5_HUMAN] 100 1 1 7 88 110 12,03704523 5,681152344 2 P60660 Myosin light polypeptide 6 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MYL6 PE=1 SV=2 - [MYL6_HUMAN] 100 3 5 17 173 151 16,91913397 4,652832031 3 Q6ZYL4 General transcription factor IIH subunit 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=GTF2H5 PE=1 SV=1 - [TF2H5_HUMAN] 98,59 1 1 4 13 71 8,048185945 4,652832031 4 P60709 Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 - [ACTB_HUMAN] 97,6 5 5 35 917 375 41,70973209 5,478027344 5 P13489 Ribonuclease inhibitor OS=Homo sapiens GN=RNH1 PE=1 SV=2 - [RINI_HUMAN] 96,75 1 12 37 173 461 49,94108966 4,817871094 6 P09382 Galectin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=LGALS1 PE=1 SV=2 - [LEG1_HUMAN] 96,3 1 7 14 283 135 14,70620005 5,503417969 7 P60174 Triosephosphate isomerase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TPI1 PE=1 SV=3 - [TPIS_HUMAN] 95,1 3 16 25 375 286 30,77169764 5,922363281 8 P04406 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 - [G3P_HUMAN] 94,63 2 13 31 509 335 36,03039959 8,455566406 9 Q15185 Prostaglandin E synthase 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PTGES3 PE=1 SV=1 - [TEBP_HUMAN] 93,13 1 5 12 74 160 18,68541938 4,538574219 10 P09417 Dihydropteridine reductase OS=Homo sapiens GN=QDPR PE=1 SV=2 - [DHPR_HUMAN] 93,03 1 1 17 69 244 25,77302971 7,371582031 11 P01911 HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, -

Smith Bacterial SBP56 Identified As a Cu-Dependent Methanethiol

Bacterial SBP56 identified as a Cu-dependent methanethiol oxidase widely distributed in the biosphere EYICE, Özge, MYRONOVA, Nataliia, POL, Arjan, CARRIÓN, Ornella, TODD, Jonathan D, SMITH, Thomas <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4246-5020>, GURMAN, Stephen J, CUTHBERTSON, Adam, MAZARD, Sophie, MENNINK-KERSTEN, Monique Ash, BUGG, Timothy Dh, ANDERSSON, Karl Kristoffer, JOHNSTON, Andrew Wb, OP DEN CAMP, Huub Jm and SCHÄFER, Hendrik Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17252/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version EYICE, Özge, MYRONOVA, Nataliia, POL, Arjan, CARRIÓN, Ornella, TODD, Jonathan D, SMITH, Thomas, GURMAN, Stephen J, CUTHBERTSON, Adam, MAZARD, Sophie, MENNINK-KERSTEN, Monique Ash, BUGG, Timothy Dh, ANDERSSON, Karl Kristoffer, JOHNSTON, Andrew Wb, OP DEN CAMP, Huub Jm and SCHÄFER, Hendrik (2018). Bacterial SBP56 identified as a Cu-dependent methanethiol oxidase widely distributed in the biosphere. The ISME journal, 1 (12), 145-160. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk OPEN The ISME Journal (2017), 1–16 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE Bacterial SBP56 identified as a Cu-dependent methanethiol oxidase widely distributed in the biosphere Özge Eyice1,2,9, Nataliia Myronova1,9, Arjan Pol3, Ornella Carrión4, Jonathan D Todd4, Tom J Smith5, Stephen J Gurman6, Adam Cuthbertson1, -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Protein Targets of Acetaminophen Covalent Binding in Rat and Mouse

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: XX XX 2021 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.736788 1 58 2 59 3 60 4 61 5 62 6 63 7 64 8 65 9 66 10 Protein Targets of Acetaminophen 67 11 68 12 Covalent Binding in Rat and Mouse 69 13 70 14 Q2 Liver Studied by LC-MS/MS 71 15 Q3 72 Q1 16 Timon Geib, Ghazaleh Moghaddam, Aimee Supinski, Makan Golizeh† and Lekha Sleno* Q4 73 17 Q5 74 18 Chemistry Department, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada Q6 75 19 76 20 Acetaminophen (APAP) is a mild analgesic and antipyretic used commonly worldwide. 77 21 78 Although considered a safe and effective over-the-counter medication, it is also the leading 22 79 23 cause of drug-induced acute liver failure. Its hepatotoxicity has been linked to the covalent 80 24 binding of its reactive metabolite, N-acetyl p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), to proteins. The 81 Edited by: 25 aim of this study was to identify APAP-protein targets in both rat and mouse liver, and to 82 26 Marcus S Cooke, 83 University of South Florida, compare the results from both species, using bottom-up proteomics with data-dependent 27 United States 84 28 high resolution mass spectrometry and targeted multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) 85 Reviewed by: 29 experiments. Livers from rats and mice, treated with APAP, were homogenized and 86 Hartmut Jaeschke, 30 University of Kansas Medical Center digested by trypsin. Digests were then fractionated by mixed-mode solid-phase extraction 87 31 Research Institute, United States prior to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). -

Differential Gene Expression in Tomato Fruit and Colletotrichum

Barad et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:579 DOI 10.1186/s12864-017-3961-6 RESEARCH Open Access Differential gene expression in tomato fruit and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides during colonization of the RNAi–SlPH tomato line with reduced fruit acidity and higher pH Shiri Barad1,2, Noa Sela3, Amit K. Dubey1, Dilip Kumar1, Neta Luria1, Dana Ment1, Shahar Cohen4, Arthur A. Schaffer4 and Dov Prusky1* Abstract Background: The destructive phytopathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides causes anthracnose disease in fruit. During host colonization, it secretes ammonia, which modulates environmental pH and regulates gene expression, contributing to pathogenicity. However, the effect of host pH environment on pathogen colonization has never been evaluated. Development of an isogenic tomato line with reduced expression of the gene for acidity, SlPH (Solyc10g074790.1.1), enabled this analysis. Total RNA from C. gloeosporioides colonizing wild-type (WT) and RNAi– SlPH tomato lines was sequenced and gene-expression patterns were compared. Results: C. gloeosporioides inoculation of the RNAi–SlPH line with pH 5.96 compared to the WT line with pH 4.2 showed 30% higher colonization and reduced ammonia accumulation. Large-scale comparative transcriptome analysis of the colonized RNAi–SlPH and WT lines revealed their different mechanisms of colonization-pattern activation: whereas the WT tomato upregulated 13-LOX (lipoxygenase), jasmonic acid and glutamate biosynthesis pathways, it downregulated processes related to chlorogenic acid biosynthesis II, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and hydroxycinnamic acid tyramine amide biosynthesis; the RNAi–SlPH line upregulated UDP-D-galacturonate biosynthesis I and free phenylpropanoid acid biosynthesis, but mainly downregulated pathways related to sugar metabolism, such as the glyoxylate cycle and L-arabinose degradation II. -

Phosphine Stabilizers for Oxidoreductase Enzymes

Europäisches Patentamt *EP001181356B1* (19) European Patent Office Office européen des brevets (11) EP 1 181 356 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.7: C12N 9/02, C12P 7/00, of the grant of the patent: C12P 13/02, C12P 1/00 07.12.2005 Bulletin 2005/49 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 00917839.3 PCT/US2000/006300 (22) Date of filing: 10.03.2000 (87) International publication number: WO 2000/053731 (14.09.2000 Gazette 2000/37) (54) Phosphine stabilizers for oxidoreductase enzymes Phosphine Stabilisatoren für oxidoreduktase Enzymen Phosphines stabilisateurs des enzymes ayant une activité comme oxidoreducase (84) Designated Contracting States: (56) References cited: DE FR GB NL US-A- 5 777 008 (30) Priority: 11.03.1999 US 123833 P • ABRIL O ET AL.: "Hybrid organometallic/enzymatic catalyst systems: (43) Date of publication of application: Regeneration of NADH using dihydrogen" 27.02.2002 Bulletin 2002/09 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY., vol. 104, no. 6, 1982, pages 1552-1554, (60) Divisional application: XP002148357 DC US cited in the application 05021016.0 • BHADURI S ET AL: "Coupling of catalysis by carbonyl clusters and dehydrigenases: (73) Proprietor: EASTMAN CHEMICAL COMPANY Redution of pyruvate to L-lactate by dihydrogen" Kingsport, TN 37660 (US) JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY., vol. 120, no. 49, 11 October 1998 (72) Inventors: (1998-10-11), pages 12127-12128, XP002148358 • HEMBRE, Robert, T. DC US cited in the application Johnson City, TN 37601 (US) • OTSUKA K: "Regeneration of NADH and ketone • WAGENKNECHT, Paul, S. hydrogenation by hydrogen with the San Jose, CA 95129 (US) combination of hydrogenase and alcohol • PENNEY, Jonathan, M. -

QM/MM Study of the Reaction Mechanism of Sulfite Oxidase

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN QM/MM study of the reaction mechanism of sulfte oxidase Octav Caldararu1, Milica Feldt 2,4, Daniela Cioloboc1, Marie-Céline van Severen1, Kerstin Starke3, Ricardo A. Mata2, Ebbe Nordlander3 & Ulf Ryde 1 Received: 29 November 2017 Sulfte oxidase is a mononuclear molybdenum enzyme that oxidises sulfte to sulfate in many Accepted: 28 February 2018 organisms, including man. Three diferent reaction mechanisms have been suggested, based on Published: xx xx xxxx experimental and computational studies. Here, we study all three with combined quantum mechanical (QM) and molecular mechanical (QM/MM) methods, including calculations with large basis sets, very large QM regions (803 atoms) and QM/MM free-energy perturbations. Our results show that the enzyme is set up to follow a mechanism in which the sulfur atom of the sulfte substrate reacts directly with the equatorial oxo ligand of the Mo ion, forming a Mo-bound sulfate product, which dissociates in the second step. The frst step is rate limiting, with a barrier of 39–49 kJ/mol. The low barrier is obtained by an intricate hydrogen-bond network around the substrate, which is preserved during the reaction. This network favours the deprotonated substrate and disfavours the other two reaction mechanisms. We have studied the reaction with both an oxidised and a reduced form of the molybdopterin ligand and quantum-refnement calculations indicate that it is in the normal reduced tetrahydro form in this protein. Molybdenum (Mo) is the only second-row transition metal that is used in biological systems1. It is employed in nitrogenases, as well as in a large group of molybdenum oxo-transfer enzymes. -

Volatile Sulfur Compounds in Coastal Acid Sulfate Soils, Northern N.S.W

VOLATILE SULFUR COMPOUNDS IN COASTAL ACID SULFATE SOILS, NORTHERN N.S.W Andrew Stephen Kinsela A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA 2007 DECLARATION ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ………………………………………………… Date …………………………………………………… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are numerous people who have assisted me throughout the course of my thesis. I therefore want to take this opportunity to thank a few of those who contributed appreciably, both directly and indirectly. First of all, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Mike Melville. Mike’s initial teachings as part of my undergraduate studies first sparked my interest in soils. Since then his continued enthusiasm on the subject has helped shape the way I approach my own work. -

Sulfur-Dependent Microbial Lifestyles: Deceptively Flexible Roles for Biochemically Versatile Enzymes Crane 141

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Sulfur-dependent microbial lifestyles: deceptively flexible roles for biochemically versatile enzymes Edward J Crane III Abstract of sulfur in a manner similar to the utilization of starch granules by yeast [1]. In a series of elegant experiments A wide group of microbes are able to “make a living” on Earth originally designed to confirm the idea that individual by basing their energetic metabolism on inorganic sulfur species of bacteria existed that exhibited defined charac- compounds. Because of their range of stable redox states, teristics (known as monomorphism) Winogradsky not only sulfur and inorganic sulfur compounds can be utilized as either provided support that the microbial community was made oxidants or reductants in a diverse array of energy-conserving up of a diverse array of defined species, he also demon- reactions. In this review the major enzymes and basic strated the first known case of chemolithotrophy, at the chemistry of sulfur-based respiration and chemolithotrophy are same time establishing the fields of geomicrobiology and outlined. The reversibility and versatility of these enzymes, microbial ecology [3]. The importance of the microbes and however, means that they can often be used in multiple ways, enzymes capable of sulfur-based chemolithoautotrophy and several cases are discussed in which enzymes which are and photoautotrophy (using sulfur compounds as energy considered to be hallmarks of a particular respiratory or and/or electron sources, respectively, in theoxidative direc- lithotrophic process have been found to be used in other, often tion) and sulfur-based respiration (in the reductive direc- opposing, metabolic processes.