Community, Connection and Cohesion During COVID-19: Beyond Us and Them Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

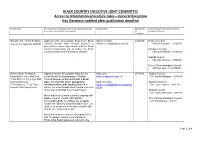

BLACK COUNTRY EXECUTIVE JOINT COMMITTEE Access to Information Procedure Rules – General Exception Key Decisions Notified After Publication Deadline

BLACK COUNTRY EXECUTIVE JOINT COMMITTEE Access to Information procedure rules – General Exception Key Decisions notified after publication deadline Project Name Key Decision to be considered (to provide adequate details for Contact Officer Date Item to Chair of relevant Overview and Scrutiny those both in and outside of the Council) be Committee informed considered Growth Hub - Grant Funding Approval for the Accountable Body for the Black Simon Neilson 24/06/20 Dudley Council Agreement Approval 2020/21 Country Growth Hub (Walsall Council) to [email protected] - Cllr Ray Burston – 11/06/20 proceed to a Grant Agreement, with the Black Country Consortium Ltd, to deliver the Black Sandwell Council Country Growth Hub Funding for 2020/21. - Cllr Laura Rollins – 15/06/20 Walsall Council - Cllr John Murray – 15/06/20 City of Wolverhampton Council - Cllr Paul Sweet – 10/06/20 Hub to Home Transport Approval for the Accountable Body for the Alan Lunt 25/09/19 Dudley Council Innovation Centre and Test Local Growth Deal programme (Walsall [email protected] - Cllr Nicola Richards – 28-8-19 Track Project: Very Light Rail Council) to proceed to enter into a Grant and Autonomous Agreement and/or other appropriate Stuart Everton Sandwell Council Technologies – Test Track documentation, with Dudley Council to [email protected] - Cllr Laura Rollins – 29-8-19 Project Grant Agreement deliver the Local Growth Deal funded elements ov.uk of the Very Light Rail Test Track Project. Walsall Council - Cllr Louise Harrison – 29-8-19 Notes that there is work currently ongoing with Dudley Council, the BC LEP and the City of Wolverhampton Council Accountable Body, to validate the available - Cllr Paul Sweet – 3-9-19 funds in the Black Country Enterprise Zone, to fund the next phases of the project which will include the Innovation Centre. -

Introduction Accessibility Across UK Local Authorities

Accessibility across UK Local Authorities Socitm and Sitemorse collaboration – supporting BetterConnected Introduction Digital accessibility regulation is challenging to manage and is negatively impacting those for whom the rules should be assisting. Public sector bodies must deal with accessibility, against a timetable. Now with a specific timeline in relation to the public sector achieving accessibility compliance for their websites, we have summarised our Q3 / 2019 results, reporting the position across the sector. For over 10 years Sitemorse have been in partnership with Socitm, working on numerous initiatives including BetterConnected. Sept. 29th 2019 | Ver. 1.9 | Release | © Sitemorse In Summary. For the Sitemorse 2019 Q3 UK Local Government INDEX we assessed over 400 authority websites for adherence to WCAG 2.1. The INDEX was compiled 37% following some 250 million tests, checks and measures across nearly 820,000 URLs. 17% Comparing the Q3 to the Q2 results; 49 improved, 44 dropped, with the balance remaining the same. Three Local Authorities achieved a score of 10 (out of 10) for accessibility. It’s important to note that the INDEX covers the main website of each authority. The law applies to all websites operated, directly or on behalf of the authority. 46% The target score is 7.7 out of 10. • Pages passing accessibility level A: 87.11% • Pages passing accessibility level AA: 12.2% • Of the 3,550 PDF’s 56.4% PDF’s passed the accessibility tests. Score 10 - 7 Score 5 - 6 Score 1 - 4 It is important to note that this score is for automated tests; there are still manual tests that need to be performed however, a score of 10 demonstrates a thorough understanding of what needs to be done and it is highly likely that the manual tests will pass too. -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40. -

Walsall Council Walsall Market Location Review and Evidence Base

Walsall Council Walsall Market Location review and evidence base ARP-WAL-EVB Planning | 10 February 2014 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 232986 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd The Arup Campus Blythe Gate Blythe Valley Park Solihull B90 8AE United Kingdom www.arup.com Walsall Council Walsall Market Location review and evidence base Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Purpose of this report 1 1.2 Arup’s commission 1 2 Key considerations 2 3 Previously considered market locations 4 3.1 Overview 4 3.2 Location requirements 5 3.3 The preferred location 5 4 Review of existing market and preferred location 6 4.1 Economic context 6 4.2 Public realm 7 4.3 Accessibility 11 4.4 Recognising best practice 11 4.5 Exclusion Zone 22 4.6 Viability 23 4.7 Civil works and infrastructure 27 4.8 Planning and regeneration context 29 5 Revised market location criteria 33 6 Potential market locations 35 6.1 Identifying potential market locations 35 6.2 Updated locations 35 7 Assessment of potential market locations 38 7.1 Assessment of locations 38 7.2 Assessment summary table 41 7.3 Preferred options 45 7.4 Recommendation 45 Tables Table 1: Soft market discussions summary Table 2: Popup stall income and expenditure Table 3: Summary of relevant local planning policy Table 4: Location criteria ARP-WAL-EVB | Planning | 10 February 2014 J:\232000\232986-00\4 INTERNAL PROJECT DATA\4-05 REPORTS\PLANNING\SUPPORTING PLANNING DOCUMENTS\EVIDENCE BASE REPORT\LOCATION REVIEW AND EVIDENCE BASE FINAL.DOCX Walsall Council Walsall Market Location review and evidence base Table 5: Potential locations assessment summary Figures Figure 1: Locations considered by GVA study. -

Street Lighting As an Asset; Smart Cities and Infrastructure Developments ADEPTE ASSOCIATION of DIRECTORS of ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING and TRANSPORT

ADEPTE ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT DAVE JOHNSON ADEPT Street Lighting Group chair ADEPT Engineering Board member UKLB member TfL Contracts Development Manager ADEPTE ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT • Financial impact of converting to LED • Use of Central Management Systems to profile lighting levels • Street Lighting as an Asset; Smart Cities and Infrastructure Developments ADEPTE ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY, PLANNING AND TRANSPORT Representing directors from county, unitary and metropolitan authorities, & Local Enterprise Partnerships. Maximising sustainable community growth across the UK. Delivering projects to unlock economic success and create resilient communities, economies and infrastructure. http://www.adeptnet.org.uk ADEPTE SOCIETY OF CHIEF OFFICERS OF CSS Wales TRANSPORTATION IN SCOTLAND ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT ADEPTE SOCIETY OF CHIEF OFFICERS OF CSS Wales TRANSPORTATION IN SCOTLAND ASSOCIATION OF DIRECTORS OF ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMY PLANNING AND TRANSPORT Bedford Borough Council Gloucestershire County Council Peterborough City Council Blackburn with Darwen Council Hampshire County Council Plymouth County Council Bournemouth Borough Council Hertfordshire County Council Portsmouth City Council Bristol City Council Hull City Council Solihull MBC Buckinghamshire County Council Kent County Council Somerset County -

Thousands of Businesses Across England Facing Further Job Losses Or Bankruptcy Due to Local Authorities Failing to Pay up to £1.4Bn of Emergency COVID-19 Grants

PRESS RELEASE Thousands of businesses across England facing further job losses or bankruptcy due to local authorities failing to pay up to £1.4bn of emergency COVID-19 grants Freedom of Information Request by the Events Industry Alliance to Local Authorities across England has shown that an estimated 87 per cent of the £1.6bn Additional Restrictions Grant (ARG) funds announced by the UK Government have yet to be paid out to companies, despite the scheme being launched four months ago The ARG scheme was announced in October to help businesses forced to close due to COVID-19 restrictions, including those in the events, exhibitions and hospitality sectors Businesses closed by COVID-19 restrictions face being forced into making further job cuts or bankruptcy due to local council delays London, 10 February 2021, The Events Industry Alliance (EIA), which represents the UK’s event organisers, venues, and suppliers, can today reveal that an estimated £1.4bn of Additional Restrictions Grants (ARG) announced by the UK Government on 31 October, has not yet been paid by local authorities in England to businesses closed by the Covid-19 pandemic. The ARG, which could be worth up to £3,000 per month per company, provides funding for local authorities to support businesses that have been forced to close because of national COVID-19 restrictions. These include companies in the retail, hospitality, and leisure sectors, as well as events and exhibitions businesses. The scheme was announced by the UK Government on 31st October 2020 with an initial £1bn funding allocation, with a further £594m issued in early January 2021. -

Winners of the Geoplace Exemplar Awards 2014

Winners of the GeoPlace Exemplar Awards 2014 Exemplar Award 2014 Winner Joint Emergency Services Group (Wales) Runner-up Oxford City Council Highly commended Northumberland County Council Custodian of the Year 2014 Marilyn George East Riding of Yorkshire Most Improved Address Data Ribble Valley Borough Council Most Improved Street Data Milton Keynes Council Best Address Data in Region Best Address Data in East Midlands Region 2014 Mansfield District Council Best Address Data in East of England Region 2014 Huntingdonshire District Council Best Address Data in Greater London Region 2014 London Borough of Enfield Best Address Data in North East Region 2014 South Tyneside Council Best Address Data in North West Region 2014 Allerdale Borough Council 1 Best Address Data in South East Region 2014 Lewes District Council Best Address Data in South East Region 2014 Adur District Council Best Address Data in South West Region 2014 Torridge District Council Best Address Data in Wales Region 2014 Flintshire County Council Best Address Data in West Midlands Region 2014 Wyre Forest District Council Best Address Data in Yorkshire and the Humber Region 2014 Kingston upon Hull City Council and Sheffield City Council Best Street Data in Region Best Street Data in East Midlands Region 2014 Northamptonshire County Council Best Street Data in East of England Region 2014 Peterborough City Council Best Street Data in Greater London Region 2014 London Borough of Enfield Best Street Data in Greater London Region 2014 London Borough of Hillingdon Best Street Data -

National Centre for Creative Health (NCCH) Safeguarding Policy

National Centre for Creative Health (NCCH) Safeguarding Policy Registered Charity No. 1190515 Policy Adopted October 2020 (Updated March 2021) Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 2 2. PART 1 – SAFEGUARDING CHILDREN ................................................................................................... 4 3. PART 2 – SAFEGUARDING ADULTS ...................................................................................................... 8 4. ENABLING REPORTS .......................................................................................................................... 11 5. CONFIDENTIALITY .............................................................................................................................. 13 6. PARTNERSHIP PROJECTS AND COLLABORATION ............................................................................. 13 7. NCCH PROGRAMME STRANDS AND DELIVERY .................................................................................. 13 8. E-SAFETY ........................................................................................................................................... 14 9. INTERNATIONAL SAFEGUARDING ...................................................................................................... 15 10. FURTHER RESOURCES .................................................................................................................... 15 11. CONTACT -

What Do I Need to Submit a Planning Application?

What do I need to submit a Planning Application? Applications for Planning Permission. This guide has been developed to assist you in the submission of planning applications across the Black Country (Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton) excluding applications for discharge of, variation of or compliance with conditions, applications for certificates of lawfulness, time extension and non-material amendments. The aim of this guide is to help applicants submit the right information with an application to ensure the Local Planning Authorities (LPA) are able to deal with your application as quickly and comprehensively as possible. Please note that not all items within this guide will be relevant to every type of planning application and you should pay particular attention to the third column which specifies the application type. This checklist brings together existing information requirements to be submitted alongside a planning application and is not intended to impose additional requirements on applicants. We strongly encourage you to obtain pre-application advice from the relevant LPA who will assist you in putting together your development proposals. Contact details for each LPA are provided at the end of this checklist. A list of policy drivers for each validation list requirement is listed in the “attached policy driver document”. The guide has been structured to help you through the submission process. Each item has been coded as follows: (S) Statutory Requirements that must be submitted in order for the application to be validated; (L) Local/Other Requirements that should be submitted as they inform the decision-making process but would not stop the application from being validated. -

BLACK COUNTRY EXECUTIVE JOINT COMMITTEE Access to Information Procedure Rules – General Exception Key Decisions Notified After Publication Deadline

BLACK COUNTRY EXECUTIVE JOINT COMMITTEE Access to Information procedure rules – General Exception Key Decisions notified after publication deadline Project Name Key Decision to be considered (to provide adequate details for those Contact Officer Date Item to Chair of relevant Overview and Scrutiny both in and outside of the Council) be Committee informed considered I9 (Blcock 9) Wolverhampton Approval for the Accountable Body for the Growth Richard Lawrence 17/04/19 Dudley Council Project Deal (Walsall Council) to proceed to a Grant Richard.Lawrence@wolverh – Cllr Crumpton – 26-3-19 Agreement with ION Projects Limited (IPL), to ampton.gov.uk deliver the Local Growth Fund (LGF), funded Sandwell Council elements of the i9 (Block 9) Wolverhampton project Cllr Laura Rollins – 19-3-19 – with delivery to commence in the 2018/19 financial Cllr Peter Hughes – 26-3-19 year. Approval for the Accountable Body for the Growth Walsall Council Deal (Walsall Council) to proceed to amending the Cllr Ian Shires – 18-3-19 existing Grant Agreement with ION Projects Limited (IPL), to deliver the Local Growth Fund Wolverhampton Council (LGF), funded elements of the i9 (Block 9) Cllr Stephen Simkins – 18-3-19 Wolverhampton project – with delivery to commence in the 2018/19 financial year. A34 Corridor Development Approval for the Accountable Body for the Growth Simon Neilson 31/07/19 Dudley Council Funding Deal (Walsall Council) to proceed to terminate the [email protected] – Cllr N Richards – 8-7-19 existing Grant Agreement of £70,000 for the A34 k Corridor Development Funding project from within Sandwell Council the Growth Deal Programme. -

Corporate Peer Challenge Follow-Up Visit to Wirral Council

Corporate Peer Challenge Follow -up visit to Wirral Council th th 8 -9 May 2013 Summary Report 1. Background and scope of the follow up visit It was a pleasure and privilege to be invited back to help Wirral Council assess the progress made since the Local Government Association (LGA) corporate peer challenge in October 2012. The peer team very much appreciated the efforts that went into preparing for the visit and looking after us whilst we were on site, and the participation of elected members, staff, partners and other stakeholders in the process. The follow up visit, as with the full peer challenge, aimed to be improvement-focussed and tailored to meet Wirral Council's needs. The visit was designed to complement and add value to your own performance and improvement focus. Peers used their experience and knowledge of local government to reflect on the information presented to them by people they meet, things they saw and material that they read. The peer team provided feedback as ‘critical friends’, not as assessors or inspectors. The peers who carried out the follow up visit to Wirral Council were all members of the original peer challenge team: Rob Vincent – former Chief Executive of Kirklees Council and Doncaster Council Councillor Peter Smith (Labour) – Leader of Wigan Council Councillor Michael White (Conservative) – Leader of Havering Council Jamie Morris – Executive Director, Walsall Council Ian Simpson – Performance Improvement Consultant Andy Bates – Principal Adviser (Peer Support) LGA Paul Clarke – LGA Peer Challenge Manager In terms of the scope and purpose of the visit, you asked the peer team to provide an external ‘stock take’ of improvement journey made since the peer challenge in October 2012 by highlighting notable progress, but more importantly by identifying areas requiring further attention, improvement and development. -

Walsall Council SAD & AAP Habitats Regulations Assessment Report

Walsall Council – SAD & AAP 2016 Walsall Council Site Allocation Document & Town Centre Area Action Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment October 2016 Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 2. Methodology 3 3. European Sites Assessed 4 3.1 Cannock Chase SAC 4 3.1.1 Background 4 3.1.2 Recreational Pressure and the Zone of influence 5 3.1.3 Visitor Frequency 8 3.1.4 Range of Activities 9 3.1.5 Socioeconomic and other factors 10 3.1.6 Residential Development Viability 11 3.1.7 Conclusion 13 3.1.8 Way Forward 13 3.2 Humber Estuary SAC/SPA/Ramsar 14 3.3 Cannock Extension Canal SAC 15 3.3.1 Background 15 3.3.2 Safeguarding the Indicative Route of the Hatherton Canal Project 16 3.3.3 Mineral Extraction 17 3.3.4 Coal and Fireclay Extraction 18 3.3.5 Conclusion 19 Page 1 of 19 Walsall Council – SAD & AAP 2016 1 Introduction The objective of this report is to provide a high level assessment of the potential for likely significant effects to European protected sites, either alone or in combination with other plans and projects, as a result of implementing the Walsall Site Allocation Document (SAD), and Walsall Town Centre Area Action Plan (AAP). The requirement for this assessment is set out within Article 6 of the EC Habitats Directive 1992, and transposed into British law by the Conservation of Habitats & Species Regulations 2010. The aim of the Directive is to “maintain or restore, at favourable conservation status, natural habitats and species of wild fauna and flora of Community interest” (Habitats Directive, Article 2(2)).