The Origin of the Gospel According to Mark Andrzej Kowalczyk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Synoptic Problem

THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM 1. The Literary Interrelationship of the Synoptic Gospels 1.1. That Matthew, Mark and Luke are similar to one another in content, the order of pericopes and in expression (style and vocabulary) is obvious to even the casual observer. (A pericope is technical term for a unit of gospel tradition.) This raises the question of why they are similar to one another in these respects. This is known as the synoptic problem. 1.1.2. In the late nineteenth century, B.F. Westcott proposed that the independent use of oral tra- dition by the three synoptic writers would account for any similarity ( An Introduction to the Study of the Gospels ). But the similarity seems too great not to postulate some sort of literary depend- ence among the synoptic gospels. This is especially true of the similarity in the order of the peric- opes and, in particular, the order of the triple tradition. It seems unlikely that the individual units of oral tradition would have been passed on in a set order, since the order of pericopes in the syn- optic gospels is generally non-chronological. 1.1.3. That the synoptic gospels are literarily related in some way becomes even more obvious when one compares the synoptic gospels to the Gospel of John. It is clear from a comparison of one of the few overlaps in content between them (outside of the Passion and Resurrection narra- tives) that the synoptic gospels are literarily related to one another. A comparison of the account of the Feeding of the 5,000 from any one of the synoptic gospels with that of the Gospel of John yields no verbatim agreement beyond what one would expect of accounts of the same event. -

The Argument from Miracles: a Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth

The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth Introduction It is a curiosity of the history of ideas that the argument from miracles is today better known as the object of a famous attack than as a piece of reasoning in its own right. It was not always so. From Paul’s defense before Agrippa to the polemics of the orthodox against the deists at the heart of the Enlightenment, the argument from miracles was central to the discussion of the reasonableness of Christian belief, often supplemented by other considerations but rarely omitted by any responsible writer. But in the contemporary literature on the philosophy of religion it is not at all uncommon to find entire works that mention the positive argument from miracles only in passing or ignore it altogether. Part of the explanation for this dramatic change in emphasis is a shift that has taken place in the conception of philosophy and, in consequence, in the conception of the project of natural theology. What makes an argument distinctively philosophical under the new rubric is that it is substantially a priori, relying at most on facts that are common knowledge. This is not to say that such arguments must be crude. The level of technical sophistication required to work through some contemporary versions of the cosmological and teleological arguments is daunting. But their factual premises are not numerous and are often commonplaces that an educated nonspecialist can readily grasp – that something exists, that the universe had a beginning in time, that life as we know it could flourish only in an environment very much like our own, that some things that are not human artifacts have an appearance of having been designed. -

Mcmaster Divinity College

McMaster Divinity College PhD CHTH G105-C05 Cynthia Long Westfall, Ph.D. MA 6ZE6 Phone: 905.525.9140 x23605 Synoptic Gospels Email: [email protected] Fall 2013 (Term 1) Mondays 3:30-5:20 p.m. I. Course Description This course provides a brief overview of the critical issues in the study of the Synoptics and a seminar-led exploration of different facets of the Synoptic Gospels by the students. The student research and presentations may include topics such as the critique and application of various synoptic methodologies, aspects of the quest for the historic Jesus, any work in a given synoptic gospel, or other topics that are limited to the study of Matthew, Mark and Luke. II. Course Objectives Specific Objectives: Through required and optional reading, lectures, class discussion, seminar presentations and assignments the student will be able to reach the following objectives: A. Knowing 1. Understand current and historical issues surrounding the Synoptic Gospels including genre, oral tradition, Q, the relationship between the Synoptics, and the historical Jesus 2. Understand critical and other contemporary methodologies that are applied to the Synoptics and how they are applied 3. Acquire a generalist understanding of the Synoptics B. Doing 1. Research a Synoptic issue or topic and write an academic paper 2. Explore and apply a suitable methodology to the selected issue or topic in the paper 3. Give presentations that simulate paper presentations in conferences and the classroom 4. Respond to another student’s paper, in writing, in presentation, and in classroom discussion, simulating the function of a respondent/participant in a conference session, and practicing skills that are applicable to academic work, including writing reviews, critiques and editorial recommendations 5. -

Evangelicals and the Synoptic Problem

EVANGELICALS AND THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM by Michael Strickland A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Dedication To Mary: Amor Fidelis. In Memoriam: Charles Irwin Strickland My father (1947-2006) Through many delays, occasioned by a variety of hindrances, the detail of which would be useless to the Reader, I have at length brought this part of my work to its conclusion; and now send it to the Public, not without a measure of anxiety; for though perfectly satisfied with the purity of my motives, and the simplicity of my intention, 1 am far from being pleased with the work itself. The wise and the learned will no doubt find many things defective, and perhaps some incorrect. Defects necessarily attach themselves to my plan: the perpetual endeavour to be as concise as possible, has, no doubt, in several cases produced obscurity. Whatever errors may be observed, must be attributed to my scantiness of knowledge, when compared with the learning and information necessary for the tolerable perfection of such a work. -

The Present State of the Synoptic Problem As Argument for a Synchronic Emphasis in Gospel Interpretation1

Streeter Versus Farmer | 7 Streeter Versus Farmer: The Present State of the Synoptic Problem as Argument for a Synchronic Emphasis in Gospel Interpretation1 David R. Bauer Asbury Theological Seminary [email protected] Abstract The dominant method for Gospel interpretation over the past several decades has been redaction criticism, which depends upon the adoption of a certain understanding of synoptic relationships in order to identify sources that lie behind our Gospels. Yet an examination of the major proposals regarding the Synoptic problem reveals that none of these offers the level of reliability necessary for the reconstruction of sources that is the presupposition for redaction criticism. This consideration leads to the conclusion that approaches to Gospel interpretation that require no reliance upon specific source theories are called for. Keywords: Synoptic problem, redaction criticism, new redaction criticism, Gospel interpretation, synchronic reading, B. H. Streeter, William R. Farmer. 1 Some minor portions of this article may be also found in Chapter 3 of my book, The Gospel of the Son of God: An Introduction to Matthew (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, forthcoming). See that chapter for a more specific treatment of the implications of synoptic relationships for the interpretation of Matthew’s Gospel. 8 | The Journal of Inductive Biblical Studies 6/2:7-28 (Summer 2019) The Problem In the book I co-authored with Robert Traina, Inductive Bible Study: A Comprehensive Guide to the Practice of Hermeneutics,2 I insisted that the employment of critical methods (e.g., source criticism and redaction criticism) contribute to the reservoir of potential types of evidence that should be considered in the interpretation of passages. -

Statistics & Q

UNIVERSITY OF REDLANDS Statistics & Q A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for honors in mathematics Bachelor of Science in Mathematics by Kirstyn Bayer April 15, 2008 Honors Committee: Professor Jim Bentley, Chairman Professor Rick Cornez Professor Steve Morics Professor Lillian Larsen Contents List of Figures Ill List of Tables iv 1 Introduction 1 2 Exploring Q 2 2.1 Composition and Genre 2 2.2 The Jesus People . 3 2.3 Matthew, Luke, & Q 4 3 The Layers of Q 5 4 The Synoptic Problem 7 4.1 Two Source Hypothesis 7 4.2 Augustinian Hypothesis 9 4.3 Farrer-Goulder Hypothesis . 9 5 Other Gospels 11 5.1 The Secret Gospel of Mark 11 5.2 The Gospel of Thomas . 12 6 The Research Process 14 6.1 Selecting a Topic 15 6.2 Assumptions 16 6.3 Finding Q . .. 16 7 The Federalist Papers 18 7.1 The Asymptotic Relationship Between the Poisson and the Negative Binomial 20 8 Statistical Tests 24 8.1 Likelihood Ratio Test 24 8.2 The Poisson Dispersion Test . 26 9 Results 28 9. 1 Future Work 28 Bibliography 31 A Appendix A 33 A.l Poisson Distribution with Mean /\ . 33 A.2 Negative Binomial with Parameters e = [r,p] 35 B Appendix B 38 List of Figures 4.1 Two Source Hypothesis . 8 4.2 Two alternative hypotheses to the Two Source hypothesis 9 iii List of Tables 7.1 Frequency distribution for war in the Federalist Papers. 20 9.1 The resulting p-values for the high-frequency words . -

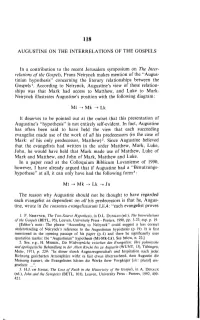

AUGUSTINE on the INTERRELATIONS of the GOSPELS in a Contribution to the Recent Jerusalem Symposium on the Inter

118 AUGUSTINE ON THE INTERRELATIONS OF THE GOSPELS In a contribution to the recent Jerusalem Symposium on The Inter- relations of the Gospels, Frans Neirynck makes mention of the "Augus- tinian hypothesis" concerning the literary relationships between the Gospels1. According to Neirynck, Augustine's view of these relation- ships was that Mark had access to Matthew, and Luke to Mark. Neirynck illustrates Augustine's Position with the following diagram: Mt -> Mk -* Lk It deserves to be pointed out at the outset that this presentation of Augustine's "hypothesis" is not entirely self-evident. In fact, Augustine has often been said to have held the view that each succeeding evangelist made use of the work of all his predecessors (in the case of Mark: of his only predecessor, Matthew)2. Since Augustine believed that the evangelists had written in the order Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, he would have held that Mark made use of Matthew, Luke of Mark and Matthew, and John of Mark, Matthew and Luke. In a paper read at the Colloquium Biblicum Lovaniense of 1990, however, I have already argued that if Augustine had a "Benutzungs- hypothese" at all, it can only have had the following form3: Mt -> Mk -> Lk -» Jn The reason why Augustine should not be thought to have regarded each evangelist äs dependent on all his predecessors is that he, Augus- tine, wrote in De consensu evangelistarum I,ii,4: "each evangelist proves 1. F. NEIRYNCK, The Two-Source Hypothesis, in D.L. DUNGAN (ed.), The Interrelations of the Gospels (BETL, 95), Leuven, University Press - Peeters, 1990, pp. -

A Viewpoint on the Supposedly Lost Gospel Q

A Viewpoint on the Supposedly Lost Gospel Q Thomas A. Wayment Thomas A. Wayment isis anan assistantassistant professorprofessor ofof ancientancient scripturescripture atat BrighamBrigham Young University. Over the past few years, it has become increasingly obvious that apathy toward the issues raised by biblical scholars is costing believing christians a great deal more than we may have anticipated. Of major concern for scholars the past two centuries is the issue of the composi- tional order of the New Testament and the literary relationship among Matthew, Mark, and Luke—commonly referred to as the synoptic Gospels. The theories presented by scholars are, in some fi elds of New Testament studies, becoming more controversial, more hostile to faith, and more reform oriented. One such fi eld of study considers the issue now known as the “synoptic problem.” The “synoptic problem” refers to the discussion surrounding how the authors of the synoptic Gos- pels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—used and referred to one another in the process of writing their own accounts. Scholarship is quite polarized over how to resolve this issue. Those who advocate a “two-document hypothesis” have heavily infl uenced the debate among scholars concerning how the Gospels were writ- ten and what sources were used in their composition.1 Their theory is that the Gospel of Mark was the earliest to be written and that it was subsequently used and borrowed from during the composition of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. This theory can adequately explain how the synoptic Gospels contain much of the same material, but there are also signifi cant portions of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke that are not found in Mark. -

Proquest Dissertations

A SOURCE CRITICAL REASSESSMENT OF THE GOSPEL OF LUKE: WAS CANONICAL MARK REALLY LUKE'S SOURCE? A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Biblical Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College By Kari Pekka Tolppanen Toronto 2009 © Kari P. Tolppanen Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53123-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53123-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Beyond the Q Impasse √ Luke«S Use of Matthew

Critical Observations on a Team Effort: Beyond the Q Impasse — Luke’s Use of Matthew I. INTRODUCTION At the 1997 CBA meeting in Seattle, David L. Dungan presented an overview of a forth- coming book, Beyond the Q Impasse — Luke’s Use of Matthew, which has since been published through the editorial work of Allan J. McNicol, himself and David B. Peabody.1 This work also represents the input of other members of the Research Team of the International Institute for Gospel Studies, William R. Farmer (who wrote the preface), Lamar Cope and Philip Shuler. The title of Dungan’s 1997 paper suggested that the Team had found “objective proof” of Luke’s use of Matthew, in support of their “Two Gospel Hypothesis” [= 2GH].2 The Team’s publication, however, does not make such an overstated claim, but seeks to give “a plausible account of the composition of the Gospel of Luke on the assumption that his major source was Matthew” (1),3 while “taking Mark completely out of the picture and dispensing with Q” (12).4 In this paper, I propose to offer an overview of the approach taken by the Team, as well as critical observations from the responses by other scholars5 and my own evaluation of the Team’s argumentation. 1Allan J. McNicol, David L. Dungan and David B. Peabody (eds.), Beyond the Q Impasse — Luke’s Use of Matthew: A Demonstration by the Research Team of the International Institute for Gospels Studies. Valley Forge PA: Trinity, 1996, xvi-333pp. — This article began as a paper for the 63rd International Meeting of the Catholic Biblical Association of America at Loyola Marymount University, August 5-8, 2000, entitled, “On Luke’s Use of Matthew. -

The Synoptic Problem

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM: A BRIEF OVERVIEW INTO THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO DR. MYRON KAUK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE COURSE NBST 521 BY SCOTT FILLMER LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA SUNDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents.....................................................................................................................2 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................3 THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM EXPLAINED .............................................................................................................3 OVERVIEW OF THE COMMON SOLUTIONS.......................................................................................................4 Four Prominent Interdependent Theories, Plus One..................................................8 THE INDEPENDENCE THEORY ...........................................................................................................................8 THE TRADITIONAL OR AUGUSTINIAN HYPOTHESIS ................................................................................... 11 THE GRIESBACH OR TWO-GOSPEL HYPOTHESIS ........................................................................................ 13 THE FARRER HYPOTHESIS .............................................................................................................................. 15 THE TWO-SOURCE HYPOTHESIS / MARKAN PRIORITY............................................................................ -

Is Q Necessary? a Source, Text, and Redaction Critical Approach to the Synoptic Problem

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2017 Is Q Necessary? A Source, Text, and Redaction Critical Approach to the Synoptic Problem Paul S. Stein College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Recommended Citation Stein, Paul S., "Is Q Necessary? A Source, Text, and Redaction Critical Approach to the Synoptic Problem" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1118. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1118 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1.0 Introduction Q, the so-called lost sayings source behind the gospels of Matthew and Luke, is often introduced to undergraduate New Testament students at the beginning of their education about the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. For some scholars, such as Burton Mack, Q represents the original words of Jesus, preserved in the Synoptic Gospels.1Others, such as Alan Kirk, have attempted to divide Q into redactional layers, determining in what order Q took shape and how the separate layers speak to different concerns of the early Christian church.2 However, no extant copy of Q exists. On some level, Q should be approached as a scholarly tool, not as an assured finding of critical New Testament scholarship.