Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Synoptic Problem

THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM 1. The Literary Interrelationship of the Synoptic Gospels 1.1. That Matthew, Mark and Luke are similar to one another in content, the order of pericopes and in expression (style and vocabulary) is obvious to even the casual observer. (A pericope is technical term for a unit of gospel tradition.) This raises the question of why they are similar to one another in these respects. This is known as the synoptic problem. 1.1.2. In the late nineteenth century, B.F. Westcott proposed that the independent use of oral tra- dition by the three synoptic writers would account for any similarity ( An Introduction to the Study of the Gospels ). But the similarity seems too great not to postulate some sort of literary depend- ence among the synoptic gospels. This is especially true of the similarity in the order of the peric- opes and, in particular, the order of the triple tradition. It seems unlikely that the individual units of oral tradition would have been passed on in a set order, since the order of pericopes in the syn- optic gospels is generally non-chronological. 1.1.3. That the synoptic gospels are literarily related in some way becomes even more obvious when one compares the synoptic gospels to the Gospel of John. It is clear from a comparison of one of the few overlaps in content between them (outside of the Passion and Resurrection narra- tives) that the synoptic gospels are literarily related to one another. A comparison of the account of the Feeding of the 5,000 from any one of the synoptic gospels with that of the Gospel of John yields no verbatim agreement beyond what one would expect of accounts of the same event. -

Here We Are at 500! the BRL’S 500 to Be Exact and What a Trip It Has Been

el Fans, here we are at 500! The BRL’s 500 to be exact and what a trip it has been. Imagibash 15 was a huge success and the action got so intense that your old pal the Teamster had to get involved. The exclusive coverage of that ppv is in this very issue so I won’t spoil it and give away the ending like how the ship sinks in Titanic. The Johnny B. Cup is down to just four and here are the representatives from each of the IWAR’s promotions; • BRL Final: Sir Gunther Kinderwacht (last year’s winner) • CWL Final: Jane the Vixen Red (BRL, winner of 2017 Unknown Wrestler League) • IWL Final: Nasty Norman Krasner • NWL Final: Ricky Kyle In one semi-final, we will see bitter rivals Kinderwacht and Red face off while in the other the red-hot Ricky Kyle will face the, well, Nasty Normal Krasner. One of these four will win The self-professed “Greatest Tag team wrestler the 4th Johnny B Cup and the results will determine the breakdown of the prizes. ? in the world” debuted in the NWL in 2012 and taunt-filled promos earned him many enemies. The 26th Marano Memorial is also down to the final 5… FIVE? Well since the Suburban Hell His “Teamster Challenge” offered a prize to any Savages: Agent 26 & Punk Rock Mike and Badd Co: Rick Challenger & Rick Riley went to a NWL rookie who could capture a Tag Team title draw, we will have a rematch. The winner will advance to face Sledge and Hammer who won with him, but turned ugly when he kept blaming the CWL bracket. -

The Argument from Miracles: a Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth

The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth Introduction It is a curiosity of the history of ideas that the argument from miracles is today better known as the object of a famous attack than as a piece of reasoning in its own right. It was not always so. From Paul’s defense before Agrippa to the polemics of the orthodox against the deists at the heart of the Enlightenment, the argument from miracles was central to the discussion of the reasonableness of Christian belief, often supplemented by other considerations but rarely omitted by any responsible writer. But in the contemporary literature on the philosophy of religion it is not at all uncommon to find entire works that mention the positive argument from miracles only in passing or ignore it altogether. Part of the explanation for this dramatic change in emphasis is a shift that has taken place in the conception of philosophy and, in consequence, in the conception of the project of natural theology. What makes an argument distinctively philosophical under the new rubric is that it is substantially a priori, relying at most on facts that are common knowledge. This is not to say that such arguments must be crude. The level of technical sophistication required to work through some contemporary versions of the cosmological and teleological arguments is daunting. But their factual premises are not numerous and are often commonplaces that an educated nonspecialist can readily grasp – that something exists, that the universe had a beginning in time, that life as we know it could flourish only in an environment very much like our own, that some things that are not human artifacts have an appearance of having been designed. -

Beginnings: Abraham: the Seeds of Faith Trusting God to Do the Right

Beginnings: Abraham: The Seeds of Faith C. God __________. Trusting God To Do The Right Thing Genesis 18:16 – 19:38 1. Jeremiah 17:9-10 March 11, 2018 By: David Wilson IV. Sin has _________________. I. God’s _______________. (verses 16-19) A. ____________ impact. A. What he will __________. (verses 16-18) B. The normal ____________. (James 1:13-15) B. How he will __________. (verse 19) V. Sin will be _______________. (verse 19:12-28) C. What he gets to __________. (verses 20-21) A. Judgment is ____________. II. _______________ with God. (verses 22-33): B. Judgment is ____________. A. _______________ C. Judgement is ___________. 1. ____________, __________, ________________. Some thoughts to take home (2 Corinthians 5:17-21): B. The _______________ Question. (verse 25) • Ministers of _________________. 1. God can do anything, but is it always the __________ • _______________ to God. thing? • Hope in __________. 2. It is only __________ that rescues Lot. III. Sin is _______________. (verses 19:1-5) This Week’s Songs: Bound For Glory A. Sodom’s ______________. Forever 10,000 Reasons (Bless The Lord) Lord I Need You 1. Ezekiel 16:49-50; Luke 17:28-30 B. Sodom’s ____________. (verses 19:4-5) Beginnings: Abraham: The Seeds of Faith b. How can Abraham’s prayer to the LORD in 18:22-33 March 11, 2018 shape the way we pray? By: Joey Tomlinson Small Group Questions *You do NOT have to answer or discuss every Question. Feel free to just pick a few. These are meant to guide you in truth. -

Woody Guthrie and the Christian Left: Jesus and “Commonism”

Briley: Woody Guthrie and the the Christian Left Woody Guthrie and the Jesus and “Commonism” Ron Briley ProducedWoody Guthrie, by The March Berkeley 8, 1943, Electronic Courtesy Press, of the 2007 Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. 1 Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 7 [2007], Iss. 1, Art. 3 Woody Guthrie and the Christian Left: Jesus and “Commonism” Following the re-election of President George W. Bush in 2004, political pundits were quick to credit Christian evangelicals with providing the margin of victory over Democratic challenger John Kerry. An article in The New York Times touted presidential adviser Karl Rove as a genius for focusing the attention of his boss upon such “moral” issues as same-sex marriage and abortion, thereby attracting four million evangelicals to the polls who had sat out the 2000 election.1 The emphasis of the Democratic Party upon such matters as jobs in the economically-depressed state of 9a Ohio apparently was trumped by the emotionally-charged issues of gay marriage and abortion, which evangelicals perceived as more threatening to their way of life than an economy in decline. This reading of the election resulted in a series of jeremiads from the political left bemoaning the influence of Christians upon Christian Left: American politics. In an opinion piece for The New York Times, liberal economist Paul Krugman termed President Bush a radical who “wants to break down barriers between church and state.” In his influential book What’s The Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank speculated as to why working-class people in Kansas, a state with a progressive tradition, would allow themselves to be manipulated by evangelists and the Republican Party into voting against their own economic interests. -

Mcmaster Divinity College

McMaster Divinity College PhD CHTH G105-C05 Cynthia Long Westfall, Ph.D. MA 6ZE6 Phone: 905.525.9140 x23605 Synoptic Gospels Email: [email protected] Fall 2013 (Term 1) Mondays 3:30-5:20 p.m. I. Course Description This course provides a brief overview of the critical issues in the study of the Synoptics and a seminar-led exploration of different facets of the Synoptic Gospels by the students. The student research and presentations may include topics such as the critique and application of various synoptic methodologies, aspects of the quest for the historic Jesus, any work in a given synoptic gospel, or other topics that are limited to the study of Matthew, Mark and Luke. II. Course Objectives Specific Objectives: Through required and optional reading, lectures, class discussion, seminar presentations and assignments the student will be able to reach the following objectives: A. Knowing 1. Understand current and historical issues surrounding the Synoptic Gospels including genre, oral tradition, Q, the relationship between the Synoptics, and the historical Jesus 2. Understand critical and other contemporary methodologies that are applied to the Synoptics and how they are applied 3. Acquire a generalist understanding of the Synoptics B. Doing 1. Research a Synoptic issue or topic and write an academic paper 2. Explore and apply a suitable methodology to the selected issue or topic in the paper 3. Give presentations that simulate paper presentations in conferences and the classroom 4. Respond to another student’s paper, in writing, in presentation, and in classroom discussion, simulating the function of a respondent/participant in a conference session, and practicing skills that are applicable to academic work, including writing reviews, critiques and editorial recommendations 5. -

Evangelicals and the Synoptic Problem

EVANGELICALS AND THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM by Michael Strickland A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Dedication To Mary: Amor Fidelis. In Memoriam: Charles Irwin Strickland My father (1947-2006) Through many delays, occasioned by a variety of hindrances, the detail of which would be useless to the Reader, I have at length brought this part of my work to its conclusion; and now send it to the Public, not without a measure of anxiety; for though perfectly satisfied with the purity of my motives, and the simplicity of my intention, 1 am far from being pleased with the work itself. The wise and the learned will no doubt find many things defective, and perhaps some incorrect. Defects necessarily attach themselves to my plan: the perpetual endeavour to be as concise as possible, has, no doubt, in several cases produced obscurity. Whatever errors may be observed, must be attributed to my scantiness of knowledge, when compared with the learning and information necessary for the tolerable perfection of such a work. -

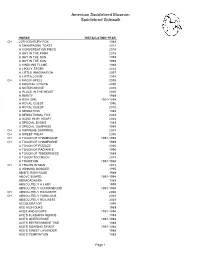

Saddlebred Sidewalk List 1989-2018

American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR CH 20TH CENTURY FOX 1989 A CHAMPAGNE TOAST 2011 A CONVERSATION PIECE 2014 A DAY IN THE PARK 2018 A DAY IN THE SUN 1999 A DAY IN THE SUN 1998 A KINDLING FLAME 1989 A LIKELY STORY 2014 A LITTLE IMAGINATION 2007 A LOTTA LOVIN' 1998 CH A MAGIC SPELL 2005 A MAGICAL CHOICE 2000 A NOTCH ABOVE 2016 A PLACE IN THE HEART 2000 A RARITY 1989 A RICH GIRL 1991-1994 A ROYAL QUEST 1996 A ROYAL QUEST 2010 A SENSATION 1989 A SENSATIONAL FOX 2002 A SONG IN MY HEART 2004 A SPECIAL EVENT 1989 A SPECIAL SURPRISE 1998 CH A SUPREME SURPRISE 2001 CH A SWEET TREAT 2000 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1991-1994 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1989 A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ 2006 A TOUCH OF RADIANCE 1995 A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS 1989 A TOUCH TOO MUCH 2018 A TRADITION 1991-1994 CH A TRAVELIN' MAN 2012 A WINNING WONDER 1995 ABIE'S IRISH ROSE 1989 ABOVE BOARD 1991-1994 ABRACADABRA 1989 ABSOLUTELY A LADY 1999 ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS 1991-1994 CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE 2005 CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS 2001 ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS 2001 ACCELERATOR 1998 ACE HIGH DUKE 1989 ACES AND EIGHTS 1991-1994 ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS 1989 ACE'S QUEEN ROSE 1991-1994 ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME 1989 ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT 1991-1994 ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER 1989 ACE'S TEMPTATION 1989 Page 1 American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR ACTIVE SERVICE 1996 ADF STRICTLY CLASS 1989 ADMIRAL FOX 1996 ADMIRAL'S AVENGER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S COMMAND 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET 1998 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK -

“ON FREEDOM's WINGS: BOUND for GLORY” the Story of The

“ON FREEDOM’S WINGS: BOUND FOR GLORY” The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II Tuskegee Airmen Lesson Plans Recommended Level: Middle School Time Required: 2 Days Introduction: These lesson plans address major areas of study in American History: racism in the 1930’s and 1940’s and the Allied campaign on the Western Front. The lessons may best be used in the context of World War II and the European Theater of action. However, lessons may also be used during Black History Month. These lesson plans and viewing of the film are prepared to take two class periods. Materials: • Video: On Freedom’s Wings – Bound for Glory • Internet resources • Textbook • Map of European Theater Unit Goals: After completing this unit, students will be able to: 1. Have an understanding of Allied strategy to defeat Hitler on the Western Front 2. Identify Allied and German leaders on the Western Front 3. Describe the racism prior and during WWII as seen in the stories of the Tuskegee Airmen 4. Describe the accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen in WWII 5. Take the role of war correspondents in reporting on the accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen either using Power Point or Publisher (Extra activity*.) 1 Day 1: Aim: The student will: 1. Examine Allied strategies to defeat Hitler in 1942 2. Describe Operation Torch and significant battles in North Africa 3. Identify the roles of Eisenhower, Montgomery and Rommel 4. Use primary sources to examine segregation in the 1930’s and how it might affect Tuskegee Airmen. Procedure: 1. In paired partners, have student examine the map of Europe and Africa to figure out the easiest and best way to beat Hitler 2. -

Voyager Reflection Quest: Bound for Glory in The

1/10/2018 Ideal-Logic Ritt Kellogg Memorial Fund Registration Registration No. S9D9-4PS2T Submitted Jan 10, 2018 8:59am by Kilian Morales Coskran Registration 2018 Ritt Kellogg Memorial Fund Waiting RKMF Expedition Grant 2017-18 Group Application for This is the group application for a RKMF Expedition Grant. If you have received approval, you may fill out Approval this application as a group. In this application you will be asked to provide important details concerning your expedition. Participant I. Expedition Summary Expedition Name Voyageur Reflection Quest: Bound for Glory in the Boundary Waters Objectives The objective of our proposed expedition is, first and foremost, to safely navigate the interlocking lakes and streams of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. In the pursuit of this objective, we will practice our backcountry navigation and travel skills. As graduating seniors, we want to reflect on our time at CC and contemplate our transition forward, into the greater world. To do this we will supplement our paddling time with journaling, yoga, watercoloring, and fishing while simultaneously making sure we live in the moment, savoring each other’s company and the remote wilderness around us. Location The Boundary Waters Canoe Area is an area of wilderness that lies below the border between Ontario and Northern Minnesota. The boundary waters is adjacent to Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park and flanked on the south west by Voyageurs National Park. The area is over one million acres in size and contains over one thousand lakes. For the majority of our trip we will follow the border between the United States and Canada as we look to delve deeply into the areas of the park with the most solitude. -

Angry Aryans Bound for Glory in a Racial Holy War: Productions of White Identity in Contemporary Hatecore Lyrics

Angry Aryans Bound for Glory in a Racial Holy War: Productions of White Identity in Contemporary Hatecore Lyrics Thesis Presented in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Roberto Fernandez Morales, B.A. Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2017 Thesis Committee: Vincent Roscigno, Advisor Hollie Nyseth Brehm Eric Schoon Copyright by Roberto Fernandez Morales 2017 Abstract The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that, over the last 20 years, there has been a steady rise in hate groups. These groups range from alternative right, Neo Confederates, White Supremacist to Odinist prison gangs and anti-Muslim groups. These White Power groups have a particular race-based ideology that can be understood relative to their music—a tool that provides central recruitment and cohesive mechanisms. White supremacist rock, called Hatecore, presents the contemporary version of the legacy of racist music such as Oi! and Rock Against Communism. Through the years, this genre produces an idealized model of white supremacist, while also speaking out against the perceived threats, goals, and attitudes within white supremacist spaces. In this thesis, I use content analysis techniques to attempt to answer two main questions. The first is: What is the ideal type of white supremacist that is explicitly produced in Hatecore music? Secondly, what are the concerns of these bands as they try to frame these within white supremacist spaces? Results show that white supremacist men are lauded as violent and racist, while women must be servile to them. Finally, white supremacist concerns are similar to previous research, but highlight growing hatred toward Islam and Asians. -

The Present State of the Synoptic Problem As Argument for a Synchronic Emphasis in Gospel Interpretation1

Streeter Versus Farmer | 7 Streeter Versus Farmer: The Present State of the Synoptic Problem as Argument for a Synchronic Emphasis in Gospel Interpretation1 David R. Bauer Asbury Theological Seminary [email protected] Abstract The dominant method for Gospel interpretation over the past several decades has been redaction criticism, which depends upon the adoption of a certain understanding of synoptic relationships in order to identify sources that lie behind our Gospels. Yet an examination of the major proposals regarding the Synoptic problem reveals that none of these offers the level of reliability necessary for the reconstruction of sources that is the presupposition for redaction criticism. This consideration leads to the conclusion that approaches to Gospel interpretation that require no reliance upon specific source theories are called for. Keywords: Synoptic problem, redaction criticism, new redaction criticism, Gospel interpretation, synchronic reading, B. H. Streeter, William R. Farmer. 1 Some minor portions of this article may be also found in Chapter 3 of my book, The Gospel of the Son of God: An Introduction to Matthew (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, forthcoming). See that chapter for a more specific treatment of the implications of synoptic relationships for the interpretation of Matthew’s Gospel. 8 | The Journal of Inductive Biblical Studies 6/2:7-28 (Summer 2019) The Problem In the book I co-authored with Robert Traina, Inductive Bible Study: A Comprehensive Guide to the Practice of Hermeneutics,2 I insisted that the employment of critical methods (e.g., source criticism and redaction criticism) contribute to the reservoir of potential types of evidence that should be considered in the interpretation of passages.