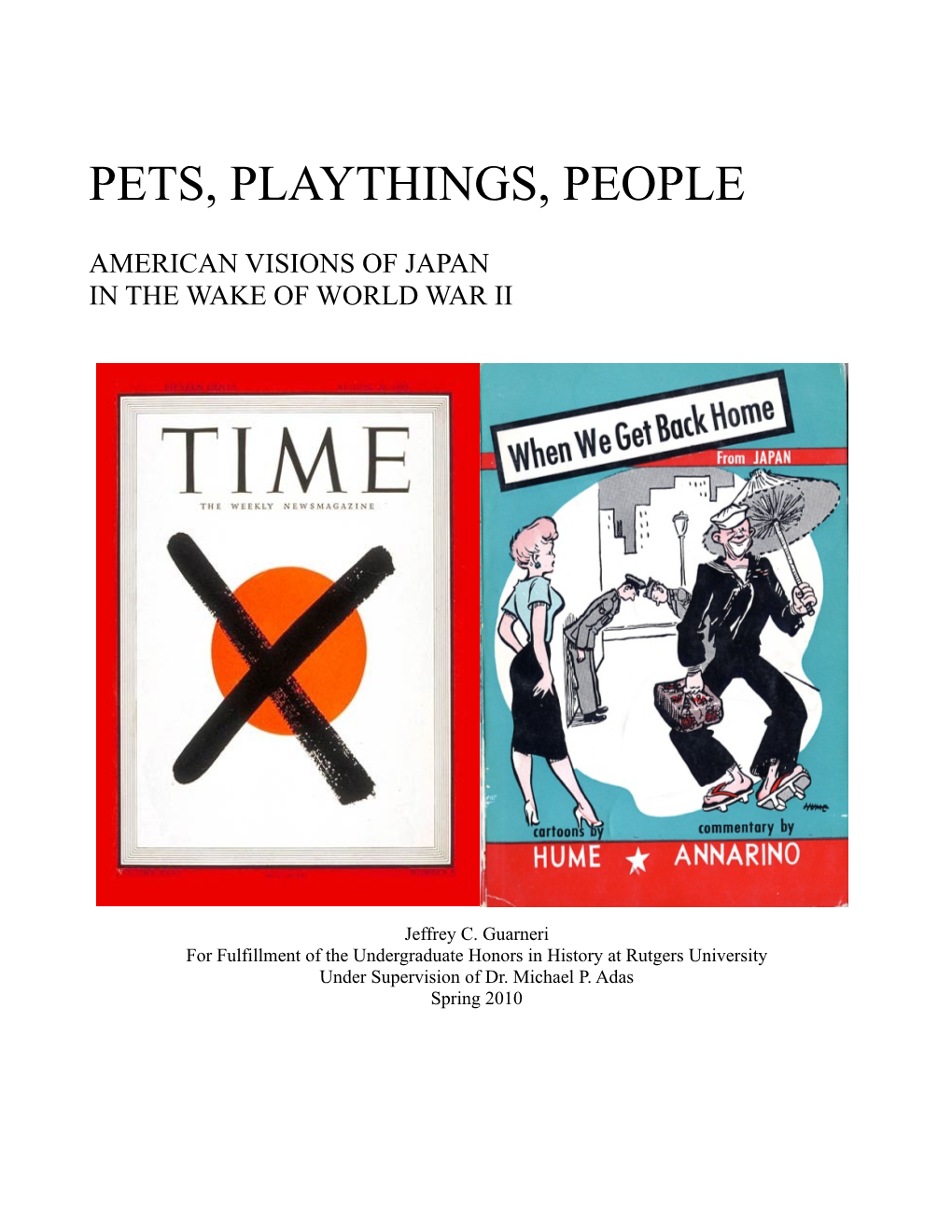

Pets, Playthings, People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration Discourses in the U.S. and in Japan Chie Torigoe

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Communication ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2011 Immigration Discourses in the U.S. and in Japan Chie Torigoe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds Recommended Citation Torigoe, Chie. "Immigration Discourses in the U.S. and in Japan." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds/25 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i IMMIGRATION DISCOURSES IN THE U.S. AND IN JAPA by CHIE TORIGOE B.A., Linguistics, Seinan Gakuin University, 2003 M.A., Communication Studies, Seinan Gakuin University, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Communication The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2011 ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of Dr. Tadasu Todd Imahori, a passionate scholar, educator, and mentor who encouraged me to pursue this path. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to those who made this challenging journey possible, memorable and even enjoyable. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mary Jane Collier. Mary Jane, without your constant guidance and positive support, I could not make it this far. Throughout this journey, you have been an amazing mentor to me. Your intelligence, keen insight and passion have always inspired me, and your warm, nurturing nature and patience helped me get through stressful times. -

Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group

HISTORICAL MATERIALS IN THE DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY OF INTEREST TO THE NAZI WAR CRIMES AND JAPANESE IMPERIAL GOVERNMENT RECORDS INTERAGENCY WORKING GROUP The Dwight D. Eisenhower Library holds a large quantity of documentation relating to World War II and to the Cold War era. Information relating to war crimes committed by Nazi Germany and by the Japanese Government during World War II can be found widely scattered within the Library’s holdings. The Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group is mandated to identify, locate and, as necessary, declassify records pertaining to war crimes committed by Nazi Germany and Japan. In order to assist the Interagency Working Group in carrying out this mission, the Library staff endeavored to identify historical documentation within its holdings relating to this topic. The staff conducted its search as broadly and as thoroughly as staff time, resources, and intellectual control allowed and prepared this guide to assist interested members of the public in conducting research on documents relating generally to Nazi and Japanese war crimes. The search covered post- war references to such crimes, the use of individuals who may have been involved in such crimes for intelligence or other purposes, and the handling of captured enemy assets. Therefore, while much of the documentation described herein was originated during the years when the United States was involved in World War II (1939 to 1945) one marginal document originated prior to this period can be found and numerous post-war items are also covered, especially materials concerning United States handling of captured German and Japanese assets and correspondence relating to clemency for Japanese soldiers convicted and imprisoned for war crimes. -

Debating the Allied Occupation of Japan (Part Two) by Peter K

Debating the Allied Occupation of Japan (Part Two) By Peter K. Frost Emperor Hirohito's first visit to Yokohama to see living conditions in the country since the end of the war, February 1946. Source: The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus website at http://tinyurl.com/h8bczpw. n the fall 2016 issue of Education About Asia, I outlined three poli- cy decisions, which I consider a fascinating way to discuss the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945–1952). The three—the decision to keep Ithe Shōwa Emperor (Hirohito) on the throne, punish selected individuals for war crimes, and create a new constitution that (in Article 9) seemed to outlaw war as an instrument of national policy—were all urged upon the Japanese by SCAP, a term for both the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers—General Douglas MacArthur until 1951—and the largely American bureaucracy. All were political reforms aimed at creating a more democratic Japan while allowing the Emperor to stay on the throne. This section discusses three more general policies aimed at reinforcing the first three by building a more equal and educated society. May Day (May 1, 1946) mass protest outside the Imperial Palace. Source: Tamiment Library and Wagner Helping Rural Japan Archives at http://tinyurl.com/j8ud948. By the end of the war, the Japanese were starving. Traditionally forced to import food from abroad, the destruction of its merchant marine, the repa- economy. “No weapon, even the atomic bomb,” he insisted, “is as deadly in triation of over three million soldiers and civilians from abroad, fertilizer its effect as economic warfare.” Although the United States was not happy shortages, and a spectacularly bad 1945 harvest all deprived the Japanese over aiding an enemy when so many of the Allied nations also needed help, of badly needed food. -

Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific Ap Ct Syrus Jin

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Research Spring 5-2019 The aC sualties of U.S. Grand Strategy: Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific aP ct Syrus Jin Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Korean Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jin, Syrus, "The asC ualties of U.S. Grand Strategy: Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific aP ct" (2019). Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses. 14. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd/14 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Casualties of U.S. Grand Strategy: Korean Exclusion from the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Pacific Pact By Syrus Jin A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Honors in History In the College of Arts and Sciences Washington University in St. Louis Advisor: Elizabeth Borgwardt 1 April 2019 © Copyright by Syrus Jin, 2019. All Rights Reserved. Jin ii Dedicated to the members of my family: Dad, Mom, Nika, Sean, and Pebble. ii Jin iii Abstract From August 1945 to September 1951, the United States had a unique opportunity to define and frame how it would approach its foreign relations in the Asia-Pacific region. -

Righting an Injustice Or American Taliban? the Removal Of

Southern New Hampshire University Righting an Injustice or American Taliban? The Removal of Confederate Statues A Capstone Project Submitted to the College of Online and Continuing Education in Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Arts in History By Andreas Wolfgang Reif Manchester, New Hampshire July 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Andreas Wolfgang Reif All Rights Reserved ii Student: Andreas Wolfgang Reif I certify that this student has met the requirements for formatting the capstone project and that this project is suitable for preservation in the University Archive. July 12, 2018 __________________________________________ _______________ Southern New Hampshire University Date College of Online and Continuing Education iii Abstract In recent years, several racial instances have occurred in the United States that have reinvigorated and demanded action concerning Confederate flags, statues and symbology. The Charleston massacre in 2015 prompted South Carolina to finally remove the Confederate battle flag from state grounds. The Charlottesville riots in 2017 accelerated the removal of Confederate statues from the public square. However, the controversy has broadened the discussion of how the Civil War monuments are to be viewed, especially in the public square. Many of the monuments were not built immediately following the Civil War, but later, during the era of Jim Crow and the disenfranchisement of African Americans during segregation in the South. Are they tributes to heroes or are they relics of a racist past that sought not to remember as much as to intimidate and bolster white supremacy? This work seeks to break up the eras of Confederate monument building and demonstrate that different monuments were built at different times (and are still being built). -

Challenge of Japanese-Peruvian Descendent Families in the XXI Century

Challenge of Japanese-Peruvian descendent families in the XXI century, Peruvian dekasegi in Japan: Overview of Socio Economic Issues of Nikkei by LAGONES VALDEZ Pilar Jakeline DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Development Doctor of Philosophy GRADUATE SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NAGOYA UNIVERSITY Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Naoko SHINKAI (Chairperson) Sanae ITO Hideto NISHIMURA Tetsuo UMEMURA Approved by the GSID Committee: March 07, 2016 1 Acknowledgements First, I would like to give my gratefulness to Professor SHINKAI Naoko, my academic advisor, for her priceless academic guidance throughout my research term at the Graduate School of International Development in Nagoya University. I achieved my goals as a graduate student with her useful and professional advices. She also gave me an invaluable guidance for my social life in Japan. She encouraged and supported me warmly. I would also like to deeply thank Professor ITO Sanae and Professor NISHIMURA Hideto, who supported me with valuable comments. I would like to appreciate Professor FRANCIS Peddie for important comments in my dissertation. I also thank to all my seminar members, who helped me with their experience and knowledge. In Japan, they became my family members. I felt so happy to meet them in my life. I appreciate the Peruvian Consul in Japan, who gave me the permission to do my interview survey to Peruvian Nikkei. I also thank to the Peruvian Nikkei community, they permitted me to enter their home to observe and interview with questions regarding to my research during my field work. -

Law in the Allied Occupation of Japan

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 8 Issue 2 Law in Japan: A Celebration of the Works of John Owen Haley 2009 The Good Occupation? Law in the Allied Occupation of Japan Yoshiro Miwa University of Tokyo J. Mark Ramseyer Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Yoshiro Miwa and J. Mark Ramseyer, The Good Occupation? Law in the Allied Occupation of Japan, 8 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 363 (2009), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol8/iss2/13 This Article & Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GOOD OCCUPATION? LAW IN THE ALLIED OCCUPATION OF JAPAN YOSHIRO MIWA J. MARK RAMSEYER∗ They left Japan in shambles. By the time they surrendered in 1945, Japan’s military leaders had slashed industrial production to 1930 levels.1 Not so with the American occupiers. By the time they left in 1952, they had rebuilt the economy and grown it by fifty percent.2 By 1960 the economy had tripled, and by 1970 tripled once more.3 For Japan’s spectacular economic recovery, the American-run Allied Occupation had apparently set the stage. The Americans had occupied, and the economy had boomed. The Americans had ruled, and Japan had thrived. -

Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History

3 ASIAN HISTORY Porter & Porter and the American Occupation II War World on Reflections Japanese Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The Asian History series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hägerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Members Roger Greatrex, Lund University Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University David Henley, Leiden University Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: 1938 Propaganda poster “Good Friends in Three Countries” celebrating the Anti-Comintern Pact Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 259 8 e-isbn 978 90 4853 263 6 doi 10.5117/9789462982598 nur 692 © Edgar A. Porter & Ran Ying Porter / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Sex and Censorship During the Occupation of Japan

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2012 Sex and censorship during the occupation of Japan Mark J. McLelland University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation McLelland, Mark J., Sex and censorship during the occupation of Japan 2012. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1536 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Sex and Censorship During the Occupation of Japan 占領下日本における性と検閲 :: JapanFocus The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus In-depth critical analysis of the forces shaping the Asia-Pacific...and the world. Home About Resources Sustainers What's Hot + - R Share this page: Print « Back Search article by Author: Sex and Censorship During the Occupation of Japan by Title: Mark McLelland This chapter entitled “Sex and Censorship During the Occupation of Japan” is excerpted from Mark McLelland’s Love, by Keyword: Sex and Democracy in Japan during the American Occupation (Palgrave MacMillan 2012). The book examines the radical changes that took place in Japanese ideas about sex, romance and male-female relations in the wake of Japan’s defeat and occupation by Allied forces at the end of the Second World War. Although there have been other studies that have focused on sexual and romantic relationships between Japanese women and US military personnel, little Region attention has been given to how the Occupation impacted upon the courtship practices of Japanese men and women. -

The US Occupation and Japan's New Democracy

36 Educational Perspectives v Volume 0 v Number 1 The US Occupation and Japan’s New Democracy by Ruriko Ku�ano Introduction barking on world conquest,” (2) complete dismantlement of Japan’s Education, in my view, is in part a process through which war–making powers, and (3) establishment of “freedom of speech, important national values are imparted from one generation to of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental the next. I was raised in affluent postwar Japan, and schooled, human rights.”2 like others of my generation, to despise the use of military force The Potsdam Declaration was unambiguous—the Allied and every form of physical confrontation. The pacifist ideal of powers urged the Japanese to surrender unconditionally now or face peace was taught as an overriding value. I was told that as long as “utter destruction.”3 But because it failed to specify the fate of the Japan maintained its pacifism, the Japanese people would live in emperor, the Japanese government feared that surrender might end peace forever. My generation were raised without a clear sense of the emperor’s life. The Japanese government chose to respond with duty to defend our homeland—we did not identify such words as “�okusatsu”—a deliberately vague but fateful word that literally “patriotism,” “loyalty,” and “national defense” with positive values. means “kill by silence”4— until the Allied powers guaranteed the Why? Postwar education in Japan, the product of the seven–year emperor’s safety. US occupation after WWII, emphasizes pacifism and democracy. I Unfortunately, the Allied powers interpreted Japanese silence, came to United States for my graduate studies in order to study how with tragic consequences, as a rejection of the declaration. -

Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ BEYOND TWO HOMELANDS: MIGRATION AND TRANSNATIONALISM OF JAPANESE AMERICANS IN THE PACIFIC, 1930-1955 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Michael Jin March 2013 The Dissertation of Michael Jin is approved: ________________________________ Professor Alice Yang, Chair ________________________________ Professor Dana Frank ________________________________ Professor Alan Christy ______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Michael Jin 2013 Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 19 The Japanese American Transnational Generation in the Japanese Empire before the Pacific War Chapter 2: 71 Beyond Two Homelands: Kibei and the Meaning of Dualism before World War II Chapter 3: 111 From “The Japanese Problem” to “The Kibei Problem”: Rethinking the Japanese American Internment during World War II Chapter 4: 165 Hotel Tule Lake: The Segregation Center and Kibei Transnationalism Chapter 5: 211 The War and Its Aftermath: Japanese Americans in the Pacific Theater and the Question of Loyalty Epilogue 260 Bibliography 270 iii Abstract Beyond Two Homelands: Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955 Michael Jin This dissertation examines 50,000 American migrants of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who traversed across national and colonial borders in the Pacific before, during, and after World War II. Among these Japanese American transnational migrants, 10,000-20,000 returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and became known as Kibei (“return to America”). Tracing the transnational movements of these second-generation U.S.-born Japanese Americans complicates the existing U.S.-centered paradigm of immigration and ethnic history. -

The Occupation of Japan: an Analysis of Three Phases of Development

Parkland College A with Honors Projects Honors Program 2015 The ccO upation of Japan: An Analysis of Three Phases of Development Adam M. Woodside Recommended Citation Woodside, Adam M., "The cO cupation of Japan: An Analysis of Three Phases of Development" (2015). A with Honors Projects. 151. https://spark.parkland.edu/ah/151 Open access to this Essay is brought to you by Parkland College's institutional repository, SPARK: Scholarship at Parkland. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Research Project HIS – 105 Adam Woodside The Occupation of Japan: An Analysis of Three Phases of Development Introduction After World War II, Europe was war-ravaged and the Pacific islands were devastated. The impact was compounded by Japan’s previous invasions of China, Korea, the East Indies and more. Additionally, the numerous Allied non-atomic and two atomic bombings in Japan caused a need for physical reconstruction. The result of these factors necessitated massive efforts to return the Pacific to a state of normalcy. Another resulting problem that was facing Japan was the need for economic reconstruction of their country. One of the main efforts that was needed was to return people back to their home country. This is called repatriation. This was especially important for Japan as they had to bring their people home from the many countries that they had previously invaded. The Allied Powers also enacted reforms and reconstruction through a military government that was put in place in Japan. This helped build Japan back up economically and included several ratified treaties. This period of reconstruction can be broken down into three separate phases.