Written Evidence Submitted by Britain's Leading Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham County Council Plan 2020-23

Durham County Council Council Plan 2020-2023 Executive Summary County Durham is a dynamic place, used to overcoming challenges and reinventing itself. Recently, the council and partners agreed a vision for County Durham for 2035 following extensive consultation with our residents. Over 30,000 responses helped shape a vision that people recognise. This is to create more and better jobs, help people live long and independent lives and support communities to be well connected and supportive of each other. Our purpose holds to deliver on these ambitions against a context of COVID-19. This plan sets out how we will achieve this. We want to create more and better jobs by supporting businesses emerging from lockdown back to stability and help to rebuild our economy. We are developing a pipeline of projects and investment plans; our roadmap to help stimulate economic recovery. We will create major employment sites across the county, cementing our position as a premier place in the region to do business. Employability support programmes will be developed to help people back into employment or to start their own business. As young people return to our schools and colleges, we will ensure that they receive a good education and training to equip them with the skills they need to access opportunities of today and the future. We will help our tourism and hospitality sector to recover as a great visitor destination with a cultural offer which will help stimulate the local economy. We want our residents to live long and independent lives and remain in good health for many years to come. -

Standards Exchange Website Extracts , Item 4. PDF 77 KB

STANDARDS ISSUES ARISEN FROM OTHER PARTS OF THE COUNTRY Cornwall Council A Cornwall councillor who said disabled children “should be put down” has been found guilty of breaching the councillors’ code of conduct – but cannot be suspended. Wadebridge East member Collin Brewer’s comments were described by a panel investigating the claims as “outrageous and grossly offensive”. Cornwall Council said it received 180 complaints about Mr Brewer following the revelation that he said disabled children should be put down as they cost the council too much – and a subsequent interview he gave to the Disability News Service after his re-election on May 2 where he likened disabled children to deformed lambs. On Friday its findings were considered by the council’s standards committee in a behind-closed-doors session. Although Mr Brewer has been found to be in breach of the Code of Conduct, the council does not have the legal power to remove him from his position as a councillor. A council spokesman said: “The authority previously had the ability to suspend councillors following the investigation and determination of Code of Conduct complaints, however, following the Government’s changes to the Code of Conduct complaints process, this sanction is no longer available.” The council said that “given the seriousness of the breach” the council’s monitoring has imposed the highest level of sanctions currently available to the council. These include: • Formally censuring Mr Brewer for the outrageous and grossly insensitive remarks he made in the telephone conversation with John Pring on May 8 and directing him to make a formal apology for the gross offensiveness of his comments and the significant distress they caused. -

Cornwall Council 2018/19 Annual Financial Report and Statement of Accounts

Information Classification: CONTROLLED Cornwall Council 2018/19 Annual Financial Report And Statement of Accounts Information Classification: CONTROLLED This page is intentionally blank Information Classification: CONTROLLED Contents Cornwall Council 2018/19 Annual Financial Report and Statement of Accounts Contents Page Narrative Report 2 Independent Auditor’s Report for Cornwall Council 25 Independent Auditor’s Report for Cornwall Pension Fund 31 Statement of Accounts Statement of Responsibilities and Certification of the Statement of Accounts 35 Main Financial Statements 37 Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement 38 Movement in Reserves Statement 38 Balance Sheet 40 Cash Flow Statement 40 Notes to the Main Financial Statements 42 Index of Notes 43 Group Financial Statements 123 Group Movement in Reserves Statement 124 Group Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement 124 Group Balance Sheet 126 Group Cash Flow Statement 126 Notes to the Group Financial Statements 128 Supplementary Financial Statements 139 Housing Revenue Account 141 Notes to the Housing Revenue Account 143 Collection Fund 149 Notes to the Collection Fund 151 Fire Fighters’ Pension Fund Account 153 Pension Fund Accounts 157 Cornwall Local Government Pension Scheme Accounts 158 Notes to the Pension Scheme Accounts 159 Glossary 189 Page 1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED Narrative Report Cornwall Council 2018/19 Statement of Accounts Narrative Report from Chief Operating Officer and Section 151 Officer I am pleased to introduce our Annual Financial Report and Statement of Accounts for 2018/19. This document provides a summary of Cornwall Council’s financial affairs for the financial year 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 and of our financial position at 31 March 2019. -

East Midlands Regional Assembly's

EAST MIDLANDS TROUBLED FAMILIES LEADS NETWORK Action Points of Meeting held at 10am, 11th October 2013, Conference Room, East Midlands Councils, Melton Mowbray In Attendance/Apologies Name Organisation Present Apology Phil Poirier DCLG Liz Perfect (LP) Derby City Council Tim Clegg Derby City Council Rob Fletcher (RF) Derbyshire County Council Judith Walker (JW) JCP/DWP Michelle Skinner Leicester City Council Andy Robinson (AR) Chair Leicestershire County Council Mags Walsh (MW) Leicestershire County Council Lynn Gibson (LG) Leicestershire SLF Programme Mark Rainey (MR) Lincolnshire County Council Alex Holloway (AH) Lincolnshire County Council Nicci Marzec (NM) Northamptonshire CC Tim O’Neill Nottingham City Council Nicky Dawson Nottingham City Council Jenny Spencer (JS) Nottinghamshire CC Helga Spry-Shute (HS-S) Rutland County Council Peter Williams (PW) EMC Kevin Thomas (KT) Working Links Pauline Grice (PG) TFEA Liz Annetts (LA) TFEA Sarah Holtham (SH) TFEA Item Subject Actions 2. Notes and Action Points of 25th June 2013 Meeting Actions Points: Action for Russ Aziz, DCLG – it was understood that claimants need to be over 18 in order for their payments to impact upon payments to other family members. Actions for AR – AR had yet to speak with Louise Casey and DCLG’s TF Unit on AR to follow up the possibility of setting up a senior level national meeting of TF leads and also to ascertain whether embargoed data could be released a day early to relevant local authorities in order to prepare a possible media response. Action for Kevin Tinsley, DCLG – Clarification was provided on the point of whether claims can be made for those that volunteer for the Work Programme as well as those that are mandated to enter it. -

Peterborough City Council & Cambridgeshire County Council

Peterborough City Council & Cambridgeshire County Council & Rutland County Council FOOD AND FEED LAW ENFORCEMENT SERVICE PLAN 2018 - 2021 1 INDEX Page Introduction 5 1. Aims and objectives of the Food and Feed Law Enforcement Service Plan 5 1.1 Aims and Objectives 1.2 The Local Picture - Contribution to Council's Strategic Priorities 2. Background 6 2.1 Area Profile - Peterborough, Cambridgeshire and Rutland 2.2 Organisational Structure 3. Food 8 3.1 Scope of the food safety and food standards function across Peterborough, Cambridgeshire and Rutland 3.2 Sampling 3.3 Demands on Environmental Health Food Service in Peterborough and Rutland 3.4 Food Hygiene Rating Scheme 3.5 Control and investigation of food poisoning outbreaks and cases of food related infectious diseases 3.6 Food complaints 3.7 Food safety incidents 3.8 Interventions 4. Feed 12 4.1 Feed premises profiles 4.2 Feed sampling 4.3 Funded inspection numbers 4.4 Feed complaints 4.5 Interventions at feed business operators 5. Enforcement Policy 13 2 6. Public Analyst 14 7. Advice to Businesses 14 8. Primary Authority Scheme 14 9. Liaison with other organisations 14 10. Promotional work and communications 15 11. Resources 16 11.1 Peterborough City Council Food Safety Team 11.2 Rutland County Council Food Safety Team 11.3 Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Trading Standards Team 12. Performance 18 13. Staff Development Plan 18 13.1 Food Standards 13.2 Food Safety 13.3 Feed 14. Quality Assessment 19 14.1 Quality assessment and internal monitoring 14.2 Service Database 15. Review 20 15.1 Review against Service Plan including variations 15.2 Service development and areas for improvement 16. -

Standards for All Archaeological Work in County Durham and Darlington

1 Standards for all Archaeological Work in County Durham and Darlington Contents Standards for all Archaeological Work in County Durham and Darlington ............................. 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 General Standards prior to commencement of fieldwork .................................................... 2 The Written Scheme of Investigation .................................................................................. 4 Fieldwork standards............................................................................................................ 8 Post excavation standards ................................................................................................ 12 Public Engagement........................................................................................................... 14 The Report ........................................................................................................................ 15 OASIS ............................................................................................................................... 17 Archiving Standards.......................................................................................................... 18 Publication ........................................................................................................................ 19 Appendix 1 Yorkshire, The Humber & The North East: A Regional Statement Of Good Practice For -

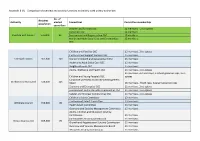

Comparison of Overview and Scrutiny Functions at Similarly Sized Unitary Authorities

Appendix B (4) – Comparison of overview and scrutiny functions at similarly sized unitary authorities No. of Resident Authority elected Committees Committee membership population councillors Children and Families OSC 12 members + 2 co-optees Corporate OSC 12 members Cheshire East Council 378,800 82 Environment and Regeneration OSC 12 members Health and Adult Social Care and Communities 15 members OSC Children and Families OSC 15 members, 2 co-optees Customer and Support Services OSC 15 members Cornwall Council 561,300 123 Economic Growth and Development OSC 15 members Health and Adult Social Care OSC 15 members Neighbourhoods OSC 15 members Adults, Wellbeing and Health OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees 21 members, 4 church reps, 3 school governor reps, 2 co- Children and Young People's OSC optees Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Management Durham County Council 523,000 126 Board 26 members, 4 faith reps, 3 parent governor reps Economy and Enterprise OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Environment and Sustainable Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Safeter and Stronger Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Children's Select Committee 13 members Environment Select Committee 13 members Wiltshere Council 496,000 98 Health Select Committee 13 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee 15 members Adults, Children and Education Scrutiny Commission 11 members Communities Scrutiny Commission 11 members Bristol City Council 459,300 70 Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny Commission 11 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Board 11 members Resources -

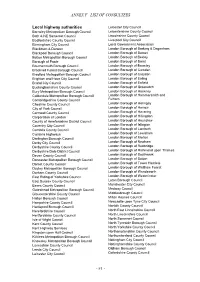

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Neighbourhood Services Environment, Health

Appendix 3 Neighbourhood Services Environment, Health and Consumer Protection Public Safety (Licensing Services Section) PUBLIC CONSULTATION ON TAXI LICENSING POLICY AND REGULATION BRIEFING PAPER ON HACKNEY CARRIAGES AND PRIVATE HIRE VEHICLE REGULATION IN COUNTY DURHAM (ZONES, THE REGULATION OF HACKNEY CARRIAGE VEHICLE NUMBERS AND COLOUR POLICY) CONTENTS Page 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Zoning 4 3.0 Zoning Options 6 3.1 Option A : Removal of the 7 zones and removal of all limits on hackney carriage numbers throughout the County of Durham 6 3.2 Option B : Retain the status quo, with seven zones, two of which are regulated and maintain the existing Limitation on hackney carriage vehicle numbers 9 3.3 Option C : Maintain the zones but with no limitations on numbers of hackney carriages 11 3.4 Option D : Maintain the zones and undertake further demand surveys in all zones 12 3.5 Option E : Removal of the 7 zones with the simultaneous removal of all limitations on hackney carriage numbers in the Chester le street and Durham City zones; and then to undertake a demand survey for the whole of the County of Durham 13 3.6 Opinions of the Department of Transport 15 3.7 Opinions of the Office of Fair Trading 15 3.8 Opinions of Durham Constabulary 15 2 3.9 Opinions of the Licensed Hackney Carriage and Private Hire Trade 3.9.1 Opinions expressed by the local Area Working Groups (AWGs) representing the hackney carriage and private hire trade associated with the existing zones. 16 3.9.2 Opinions expressed by the County Wide Working Group (CWG) comprising representatives from the 7 AWGs whose membership represents the hackney carriage and private hire trade associated with the existing zones. -

Cornwall Council) (Respondent) V Secretary of State for Health (Appellant)

Trinity Term [2015] UKSC 46 On appeal from: [2014] EWCA Civ 12 JUDGMENT R (on the application of Cornwall Council) (Respondent) v Secretary of State for Health (Appellant) R (on the application of Cornwall Council) (Respondent) v Somerset County Council (Appellant) before Lady Hale, Deputy President Lord Wilson Lord Carnwath Lord Hughes Lord Toulson JUDGMENT GIVEN ON 8 July 2015 Heard on 18 and 19 March 2015 Appellant (Secretary of Respondent (Cornwall State for Health) Council) Clive Sheldon QC David Lock QC Deok-Joo Rhee Charles Banner (Instructed by (Instructed by Cornwall Government Legal Council Legal Services) Department) Appellant /Intervener (Somerset County Council) David Fletcher (Instructed by Somerset County Council Legal Services Department) Intervener (South Gloucestershire Council) Helen Mountfield QC Sarah Hannett Tamara Jaber (Instructed by South Gloucestershire Council Legal Services) Intervener (Wiltshire Council) Hilton Harrop-Griffiths (Instructed by Wiltshire Council Legal Services) LORD CARNWATH: (with whom Lady Hale, Lord Hughes and Lord Toulson agree) Introduction 1. PH has severe physical and learning disabilities and is without speech. He lacks capacity to decide for himself where to live. Since the age of four he has received accommodation and support at public expense. Until his majority in December 2004, he was living with foster parents in South Gloucestershire. Since then he has lived in two care homes in the Somerset area. There is no dispute about his entitlement to that support, initially under the Children Act 1989, and since his majority under the National Assistance Act 1948. The issue is: which authority should be responsible? 2. This depends, under sections 24(1) and (5) of the 1948 Act, on, where immediately before his placement in Somerset, he was “ordinarily resident”. -

Universal Credit National Expansion

Universal Credit national expansion – Tranches One and Two Following the successful roll out of Universal Credit in the north-west of England, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) can provide details of the first and second tranches of national expansion to local authorities and jobcentre areas. Universal Credit will roll out to new claims from single people, who would otherwise have been eligible for Jobseeker’s Allowance, including those with existing Housing Benefit and Working Tax Credit claims. The list below confirms the go live dates for Tranches One and Two which will begin to deliver Universal Credit between February and July 2015. The Commencement Order for Tranches One and Two of national expansion, which confirmed the areas that will be going live, can be accessed here: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/101/pdfs/uksi_20150101_en.pdf And the list of postcodes that will be going live can be accessed here – https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/402501/ universal-credit-index-of-relevant-districts.pdf This list is in alphabetical order by local authority. Tranche One: February 2015 – April 2015 Local authority Jobcentre area Go live date Ashford Borough Council Ashford JCP 13 April 2015 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Barnsley JCP 2 March 2015 Goldthorpe JCP Wombwell JCP Basildon Council Basildon JCP 16 March 2015 Bassetlaw District Council Retford JCP 23 February 2015 Worksop JCP Bedford Borough Council Bedford JCP 2 March 2015 Birmingham City Council Broad Street JCP 13 April -

East Cowes Town Council

East Cowes Town Council Town Hall, York Avenue, East Cowes, Isle of Wight, PO32 6R Tel: (01983) 299082 Email: [email protected] Minutes of a meeting of East Cowes Town Council held remotely by Zoom on 18th February 2021 at 6pm Present Chair: Cllr Rann (Mayor) Councillors: Love (Deputy Mayor), Packham, Lloyd, Hendry, Webster, Walker, Palin Clerk: S Chilton Assistant Clerk: C Gale Also present: John Cattle, Zoe Thomson, Laura Reid (Youth Worker) and 7 members of the public Public Forum • A member of the public asked if a touring caravan abandoned on Kingston Road is being dealt with. It has been reported to Island Roads and the owner has been contacted. • A member of the public asked if Saunders Way has been adopted. Cllr Hendry stated that Isle of Wight Council, Island Roads and Barratts had reached agreement. A consultation on the speed limit which concludes on 5th March must be completed before further work can be done. • A member of the public raised concerns about the impact of the completion of Saunders Way on other routes and parking in the town. He will email the ward councillors with his questions for them to follow up. One minutes silence was held in memory of the Facilities Officer Mick Collis who sadly passed away in January. Meeting opened at 6.15p.m. 15/21 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE No apologies for absence were received. 16/21 DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS 2.1 Cllr Palin declared a non-pecuniary interest as a member of the Floating Bridge Stakeholders Group. Cllr Hendry declared a non-pecuniary interest as Ward Councillor for Whippingham and Osborne.