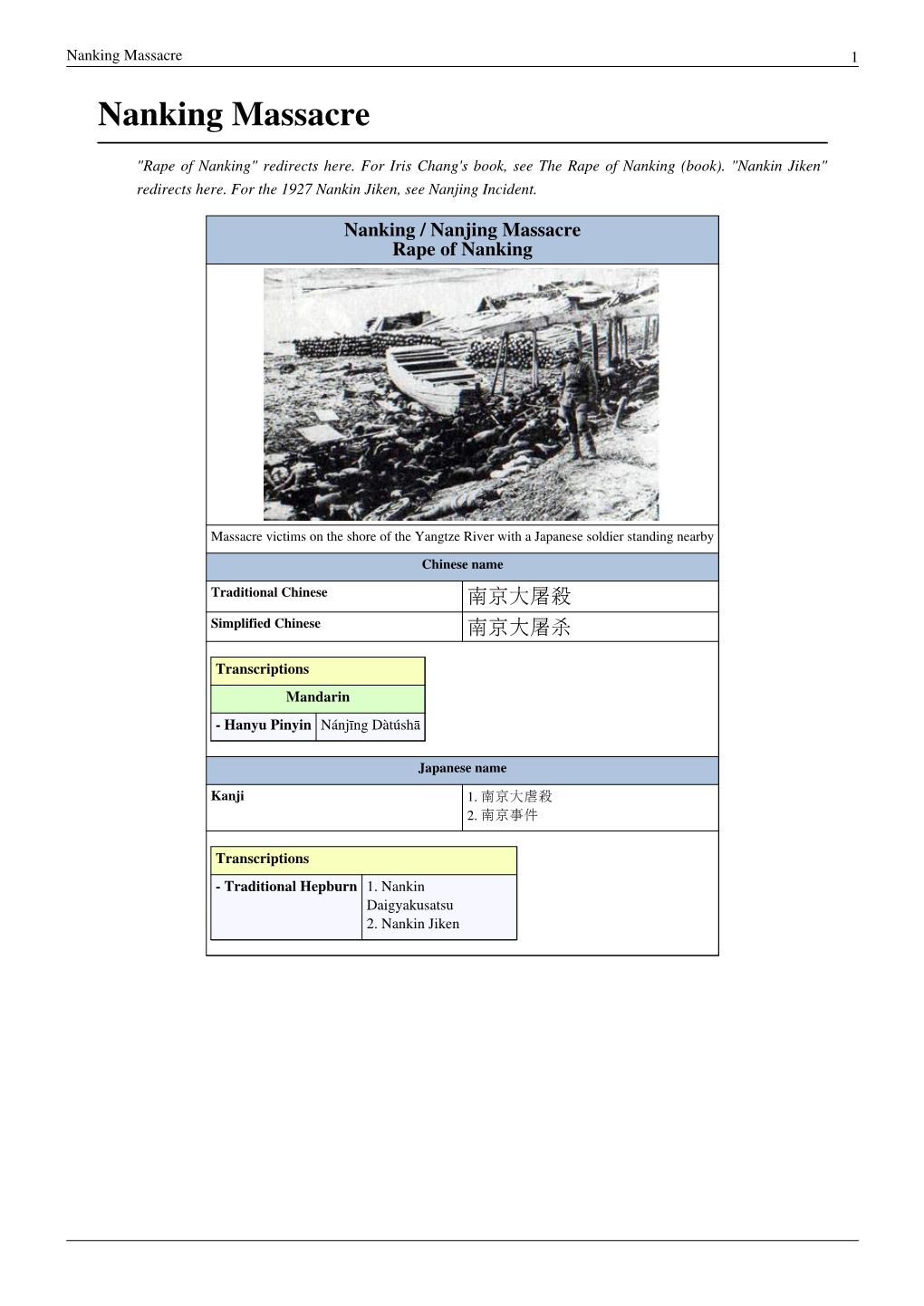

Nanking Massacre 1 Nanking Massacre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Russia Tried to Start a Race War in the United States

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 24 2019 Virtual Hatred: How Russia Tried to Start a Race War in the United States William J. Aceves California Western School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Communications Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation William J. Aceves, Virtual Hatred: How Russia Tried to Start a Race War in the United States, 24 MICH. J. RACE & L. 177 (2019). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol24/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRTUAL HATRED: HOW RUSSIA TRIED TO START A RACE WAR in the UNITED STATES William J. Aceves* During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the Russian government engaged in a sophisticated strategy to influence the U.S. political system and manipulate American democracy. While most news reports have focused on the cyber-attacks aimed at Democratic Party leaders and possible contacts between Russian officials and the Trump presidential campaign, a more pernicious intervention took place. Throughout the campaign, Russian operatives created hundreds of fake personas on social media platforms and then posted thousands of advertisements and messages that sought to promote racial divisions in the United States. This was a coordinated propaganda effort. -

Hirohito the Showa Emperor in War and Peace. Ikuhiko Hata.Pdf

00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page i HIROHITO: THE SHO¯ WA EMPEROR IN WAR AND PEACE 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page ii General MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito photographed in the US Embassy, Tokyo, shortly after the start of the Occupation in September 1945. (See page 187) 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page iii Hirohito: The Sho¯wa Emperor in War and Peace Ikuhiko Hata NIHON UNIVERSITY Edited by Marius B. Jansen GLOBAL ORIENTAL 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page iv HIROHITO: THE SHO¯ WA EMPEROR IN WAR AND PEACE by Ikuhiko Hata Edited by Marius B. Jansen First published in 2007 by GLOBAL ORIENTAL LTD P.O. Box 219 Folkestone Kent CT20 2WP UK www.globaloriental.co.uk © Ikuhiko Hata, 2007 ISBN 978-1-905246-35-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library Set in Garamond 11 on 12.5 pt by Mark Heslington, Scarborough, North Yorkshire Printed and bound in England by Athenaeum Press, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page vi 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page v Contents The Author and the Book vii Editor’s Preface -

The Rape of Nanking: a Historical Analysis of the Aftershocks of Wartime Sexual Violence in International Relations

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS HUMANAS Y SOCIALES The Rape of Nanking: a historical analysis of the aftershocks of wartime sexual violence in international relations. Autor: Ester Brito Ruiz Quinto Curso del Doble Grado de ADE y Relaciones Internacionales Director: Jose Manuel Saenz Rotko Madrid Junio 2018 Ester Brito Ruiz international relations. The Rape of Nanking: a historical analysis of the aftershocks of wartime sexual violence in in violence sexual wartime of aftershocks the of analysis historical a Nanking: of Rape The Index 1) Abstract & Key words. 2) Methodology & Research Design. 3) Introduction. 4) Historiography and debates on Nanking. 5) Historical analysis and drivers of the Second Sino-Japanese war and interbellum change in protocols against foreign combatants and civilians. a. Conditioning Japanese political factors. b. Economic drivers. c. The role of the international order. 6) The route to Nanking a. Introduction: planning and intent of Japanese imperial forces when entering Manchuria. b. Road to Nanking: the advance of the imperial army, Loot all, kill all, burn all imperative. c. The entry into the city and mass killings. d. Rape in Nanking and beyond the capital. e. Torture inflicted upon combatants and civilians. f. The weeks following the fall of Nanking. 7) Radicalization of the Japanese imperial army: understanding historical warfare practices and theories of violence. 8) Rape as a weapon of war. 9) Other war crimes and implications of Japanese Imperialism 10) Historical memory of Nanking a. Significance of diverging historical memory in politics b. China: the century of humiliation narrative c. Japan: the historical aggressor-victim dilemma 1 11) Historical impact of Nanking on current international relations. -

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

Park Statue Politics World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States

Park Statue Politics World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States THOMAS J. WARD & WILLIAM D. LAY i Park Statue Politics World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States THOMAS J. WARD AND WILLIAM D. LAY ii E-International Relations www.E-IR.info Bristol, England 2019 ISBN 978-1-910814-50-5 This book is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license. You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission. Please contact [email protected] for any such enquiries, including for licensing and translation requests. Other than the terms noted above, there are no restrictions placed on the use and dissemination of this book for student learning materials/scholarly use. Production: Michael Tang Cover Image: Ki Young via Shutterstock A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. iii E-IR Open Access Series Editor: Stephen McGlinchey Books Editor: Cameran Clayton Editorial Assistants: Xolisile Ntuli and Shelly Mahajan E-IR Open Access is a series of scholarly books presented in a format that preferences brevity and accessibility while retaining academic conventions. -

Teaching About the Nanking Massacre Yale Divinity School Library School Divinity Yale

Teaching About the Nanking Massacre Yale Divinity School Library School Divinity Yale Also includes— The First War Hawks: The Invasion of Canada in 1812 A National Council for the Social Studies Publication Number 45 September 2012 www.socialstudies.org Middle Level Learning 44 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies Teaching About the Nanking Massacre to Middle School Students Justin Villet In 1937, the Japanese Empire declared war on China. That • How can instruction be used to avoid creating stereo- December, the Japanese Army invaded and captured the types? Chinese capital of Nanking (also “Nanjing”). In what can only • Would students be able to contextualize these events, be described as one of the most inhumane events in the modern or, to put it bluntly, would they care at all? world, more than 200,000 Chinese were killed and more than 20,000 women were raped in less than a year.1 East Asian scholar Vera Schwarcz, in her contribution American public schools do not seem to devote much time to the book Nanking 1937: Memory and Healing, wrote, to the Nanking Massacre, taking a much more Eurocentric “[O]nly by delving into the crevices of helplessness and dread view of World War II. will [people] be able to pass on the true gift of historical When I was in high school, the Japanese invasion of Nanking consciousness.”2 Historical consciousness, however, should was still a new topic in the curriculum. I recall the eleventh grade be balanced with a realization that subject matter can sometimes English class looking at posters in the library that had been be hurtful to students, that material presented in class should assembled by a civic group that wanted to promote awareness be developmentally appropriate, and that teachers must be about the event. -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

Praca Doktorska.Pdf (7.461MB)

UNIWERSYTET ŁÓDZKI WYDZIAŁ STUDIÓW MIĘDZYNARODOWYCH I POLITOLOGICZNYCH Izabela Plesiewicz-Świerczyńska WYKŁADNIE IDEOLOGICZNE STOSUNKÓW JAPOŃSKO-AMERYKAŃSKICH W LATACH 1853–1941 ORAZ ICH IMPLEMENTACJA POLITYCZNA Praca doktorska napisana pod kierunkiem dr hab. Jolanty Młodawskiej-Bronowskiej, prof. nadzw. UŁ Łódź 2017 SPIS TREŚCI Nota redakcyjna……………………………………………………………….. .................... 3 WSTĘP………………………………………………………………………… .................... 5 ROZDZIAŁ 1 Inspiracje ideologiczne formuł konceptualnych w sferze międzynarodowych stosunków politycznych między Japonią a USA ................................ 24 1.1 Doktryna izolacjonizmu w okresie sakoku w Japonii od XVII do XIX wieku ............. 24 1.2 Geneza i charakterystyka doktryny izolacjonizmu w Stanach Zjednoczonych po zaistnieniu na forum międzynarodowym w 1776 roku ........................................... 39 1.3 Rozwój japońskiego ekspansjonizmu drogą do dominacji nad krajami Azji Południowo-Wschodniej ............................................................................................... 51 1.4 Argumenty zwolenników rozszerzania wpływów politycznych i ekonomicznych Stanów Zjednoczonych w świecie ................................................................................ 58 1.5 Imperializm japoński jako teoretyczna wykładnia konfliktów i wojen ........................ 68 1.6 Opinie elit politycznych USA na temat ideologii im perialistycznej w praktyce ......... 76 1.7 Filozoficzne zaplecze japońskiego nacjonalizmu ........................................................ -

Tsutomu Nishioka Kanji Katsuoka

Basic Research on Chinese Comfort Women:A Critique of Chinese Comfort Women Group for Research on Chinese Comfort Women Representative: Tsutomu Nishioka Kanji Katsuoka Minoru Kitamura Yoichi Shimada Shiro Takahashi (Listed according to the order in which their contributions appear in this report) June 17, 2016 General Statement/Overview of the Chinese Comfort Women Issue: Four Serious Flaws in Chinese Claims Tsutomu Nishioka, Representative, Group for Research on Chinese Comfort Women (Professor, Tokyo Christian University) Introduction On December 31, 2015, CNN quoted Chinese Professor Su Zhiliang in reporting that the actual total number of comfort women was 400,000, of which 200,000 were Chinese women forced into unpaid prostitution. This was reported immediately after the announcement that an agreement had been reached between Japan and South Korea on the comfort women issue. While the unfounded and slanderous accusation that there were 200,000 sex slaves has spread worldwide, some Chinese professors are now claiming that there were in fact double that number. Su Zhiliang—who is the head of the Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women" at Shanghai Normal University and co- authored in 2014 the English-language book entitled Chinese Comfort Women—is disseminating the accusation that the Japanese military had a total of 400,000 comfort women, out of which 200,000 were Chinese, and that many of these women were murdered. He played a key role in the submission of an application for documents related to Chinese comfort women to be registered as part of UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in June 2014. However, the registration was withdrawn because of advice that the application should be filed jointly with other relevant countries. -

THE GLOBALIZATION of K-POP by Gyu Tag

DE-NATIONALIZATION AND RE-NATIONALIZATION OF CULTURE: THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP by Gyu Tag Lee A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA De-Nationalization and Re-Nationalization of Culture: The Globalization of K-Pop A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Gyu Tag Lee Master of Arts Seoul National University, 2007 Director: Paul Smith, Professor Department of Cultural Studies Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2013 Gyu Tag Lee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wife, Eunjoo Lee, my little daughter, Hemin Lee, and my parents, Sung-Sook Choi and Jong-Yeol Lee, who have always been supported me with all their hearts. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation cannot be written without a number of people who helped me at the right moment when I needed them. Professors, friends, colleagues, and family all supported me and believed me doing this project. Without them, this dissertation is hardly can be done. Above all, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their help throughout this process. I owe my deepest gratitude to Dr. Paul Smith. Despite all my immaturity, he has been an excellent director since my first year of the Cultural Studies program. -

The Diaspora of Korean Children: a Cross-Cultural Study of the Educational Crisis in Contemporary South Korea

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2007 The Diaspora of Korean Children: A Cross-Cultural Study of the Educational Crisis in Contemporary South Korea Young-ee Cho The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cho, Young-ee, "The Diaspora of Korean Children: A Cross-Cultural Study of the Educational Crisis in Contemporary South Korea" (2007). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1244. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1244 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIASPORA OF KOREAN CHILDREN: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY OF THE EDUCATIONAL CRISIS IN CONTEMPORARY SOUTH KOREA By Young-ee Cho B.A Economics / East Asian Languages and Cultures, Indiana University, 1986 M.B.A. International Marketing, Indiana University, 1988 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Montana Missoula, MT Summer 2007 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School Dr. Roberta D. Evans, Chair School of Education Dr. C. LeRoy Anderson Dept of Sociology Dr. John C. Lundt Dept of Educational Leadership & Counseling Dr. William P. McCaw Dept of Educational Leadership & Counseling Dr. John C. -

John W. Dower. Embracing Defeat. Japan in the Wake of World War II

John W. Dower. Embracing Defeat. Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999. 676 pp. $29.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-393-04686-1. Reviewed by Mark Selden Published on H-Asia (October, 1999) Embracing Defeat, John Dower's magisterial refashion another society as a democratic nation. chronicle of Japan under U.S. occupation, is the "Initially," Dower tells us with characteristic inci‐ summa of his four important studies of twentieth- siveness and irony, "the Americans imposed a century Japan and the U.S.-Japan relationship.[1] root-and-branch agenda of 'demilitarization and Its sweep is ambitious, ranging from political and democratization' that was in every sense a re‐ diplomatic history to innovative attempts to lo‐ markable display of arrogant idealism-both self- cate the Japanese people in the fow of change, in‐ righteous and genuinely visionary." (p. 23) Draw‐ cluding the frst efforts to chart cultural and social ing on a wealth of archival, documentary and dimensions of the era. Central to the work, and to published sources to illuminate kaleidoscopic Ja‐ the continuing debate about the occupation, are panese and American perspectives, he highlights three intertwined political issues whose resolu‐ MacArthur's arrogance and peccadilloes while tion would profoundly affect Japan's postwar positively assessing American contributions to an course: the emperor, the constitution and democ‐ enduring democratic political transformation. ratization, and the war crimes tribunals. In taking "Never," he concludes, "had a genuinely demo‐ discussion of these and other issues far beyond cratic revolution been associated with military the official record, Dower offers fresh social and dictatorship, to say nothing of a neocolonial mili‐ cultural perspectives on Japan and the U.S.-Japan tary dictatorship .