Low Utilisation of Diabetes Medicines in Iran, Despite Their Affordability (2000–2012): a Time-Series and Benchmarking Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![LANTUS® (Insulin Glargine [Rdna Origin] Injection)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0369/lantus%C2%AE-insulin-glargine-rdna-origin-injection-60369.webp)

LANTUS® (Insulin Glargine [Rdna Origin] Injection)

Rev. March 2007 Rx Only LANTUS® (insulin glargine [rDNA origin] injection) LANTUS® must NOT be diluted or mixed with any other insulin or solution. DESCRIPTION LANTUS® (insulin glargine [rDNA origin] injection) is a sterile solution of insulin glargine for use as an injection. Insulin glargine is a recombinant human insulin analog that is a long-acting (up to 24-hour duration of action), parenteral blood-glucose-lowering agent. (See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). LANTUS is produced by recombinant DNA technology utilizing a non- pathogenic laboratory strain of Escherichia coli (K12) as the production organism. Insulin glargine differs from human insulin in that the amino acid asparagine at position A21 is replaced by glycine and two arginines are added to the C-terminus of the B-chain. Chemically, it is 21A- B B Gly-30 a-L-Arg-30 b-L-Arg-human insulin and has the empirical formula C267H404N72O78S6 and a molecular weight of 6063. It has the following structural formula: LANTUS consists of insulin glargine dissolved in a clear aqueous fluid. Each milliliter of LANTUS (insulin glargine injection) contains 100 IU (3.6378 mg) insulin glargine. Inactive ingredients for the 10 mL vial are 30 mcg zinc, 2.7 mg m-cresol, 20 mg glycerol 85%, 20 mcg polysorbate 20, and water for injection. Inactive ingredients for the 3 mL cartridge are 30 mcg zinc, 2.7 mg m-cresol, 20 mg glycerol 85%, and water for injection. The pH is adjusted by addition of aqueous solutions of hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. LANTUS has a pH of approximately 4. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action: The primary activity of insulin, including insulin glargine, is regulation of glucose metabolism. -

Comparison of Adjunctive Therapy with Metformin and Acarbose in Patients with Type-1 Diabetes Mellitus

Original Article Comparison of adjunctive therapy with metformin and acarbose in patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus Amir Ziaee1, Neda Esmailzadehha2, Maryam Honardoost3 ABSTRACT Objective: All the aforementioned data have stimulated interest in studying other potential therapies for T1DM including noninsulin pharmacological therapies. The present study attempts to investigate the effect of adjunctive therapy with metformin and acarbose in patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus. Method: In a single-center, placebo-controlled study (IRCT201102165844N1) we compared the results of two clinical trials conducted in two different time periods on 40 patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus. In the first section, metformin was given to the subjects.After six months, metformin was replaced with acarbose in the therapeutic regimen. In both studies, subjects were checked for their BMI, FBS, HbA1C, TGs, Cholesterol, LDL, HDL, 2hpp, unit of NPH and regular insulin variations. Results: Placebo-controlled evaluation of selected factors has showna significant decrease in FBS and TG levels in the metformin group during follow up but acarbose group has shown substantial influence on two hour post prandial (2hpp) and regular insulin intake decline.Moreover, Comparison differences after intervention between two test groups has shown that metformin has had superior impact on FBS and HbA1C decline in patients. Nonetheless, acarbose treatment had noteworthy influence on 2hpp, TGs, Cholesterol, LDL, and regular insulin intake control. Conclusion: The results of this experiment demonstrate that the addition of acarbose or metformin to patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus who are controlled with insulin is commonly well tolerated and help to improve metabolic control in patients. -

Diabetes Mellitus: Patterns of Pharmaceutical Use in Manitoba

Diabetes Mellitus: Patterns of Pharmaceutical Use in Manitoba by Kim¡ T. G. Guilbert A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Faculty of Pharmacy The University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba @ Kimi T.G. Guilbert, March 2005 TIIE UMYERSITY OF MANITOBA F'ACULTY OF GRADUATE STTJDIES +g+ù+ COPYRIGIIT PERMISSION PAGE Diabetes Mellitus: Patterns of Pharmaceutical Use in Manitoba BY Kimi T.G. Guilbert A ThesisÆracticum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE KIMI T.G. GTIILBERT O2()O5 Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfïlm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfilm Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither this thesis/practicum nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author's written permission. Acknowledgements Upon initiation of this project I had a clear objective in mind--to learn more. As with many endeavors in life that are worthwhile, the path I have followed has brought me many places I did not anticipate at the beginning of my journey. ln reaching the end, it is without a doubt that I did learn more, and the knowledge I have been able to take with me includes a wider spectrum than the topic of population health and medication utilization. -

Soliqua – Criteria

Criteria Based Consultation Prescribing Program CRITERIA FOR DRUG COVERAGE Insulin glargine; lixisenatide (Soliqua) subcutaneous injection Initiation (new start) criteria: Non-formulary lixisenatide/glargine (Soliqua) will be covered on the prescription drug benefit when the following criteria are met: Must meet criteria for both individual agents lixisenatide and insulin glargine. Criteria for lixisenatide: • Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus • Intolerance to preferred GLP-1 agonists liraglutide (Victoza) AND injectable semaglutide (Ozempic) • No personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN 2) • No personal history of gastroparesis • On maximally tolerated metformin dose (dose appropriate per renal function) or allergy or intolerance* to metformin (includes both metformin IR and XR) • And meets one of the following criteria: o Inadequate glycemic response on both basal and bolus insulin despite high dose requirements (total daily insulin dose of 1.5 units per kilogram of body weight or more OR greater than 200 units) OR o Has experienced recurrent nocturnal hypoglycemia with basal insulin defined as: 3 or more episodes of nocturnal hypoglycemia (BG less than 70 mg/dL) over the preceding 30 days that persists despite basal insulin dose reduction (including decrease in NPH dose and subsequent switch to and dose adjustment of insulin glargine) Criteria for insulin glargine • Use in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus as basal insulin -OR- • Use in patients with -

Type 2 Diabetes Adult Outpatient Insulin Guidelines

Diabetes Coalition of California TYPE 2 DIABETES ADULT OUTPATIENT INSULIN GUIDELINES GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS Start insulin if A1C and glucose levels are above goal despite optimal use of other diabetes 6,7,8 medications. (Consider insulin as initial therapy if A1C very high, such as > 10.0%) 6,7,8 Start with BASAL INSULIN for most patients 1,6 Consider the following goals ADA A1C Goals: A1C < 7.0 for most patients A1C > 7.0 (consider 7.0-7.9) for higher risk patients 1. History of severe hypoglycemia 2. Multiple co-morbid conditions 3. Long standing diabetes 4. Limited life expectancy 5. Advanced complications or 6. Difficult to control despite use of insulin ADA Glucose Goals*: Fasting and premeal glucose < 130 Peak post-meal glucose (1-2 hours after meal) < 180 Difference between premeal and post-meal glucose < 50 *for higher risk patients individualize glucose goals in order to avoid hypoglycemia BASAL INSULIN Intermediate-acting: NPH Note: NPH insulin has elevated risk of hypoglycemia so use with extra caution6,8,15,17,25,32 Long-acting: Glargine (Lantus®) Detemir (Levemir®) 6,7,8 Basal insulin is best starting insulin choice for most patients (if fasting glucose above goal). 6,7 8 Start one of the intermediate-acting or long-acting insulins listed above. Start insulin at night. When starting basal insulin: Continue secretagogues. Continue metformin. 7,8,20,29 Note: if NPH causes nocturnal hypoglycemia, consider switching NPH to long-acting insulin. 17,25,32 STARTING DOSE: Start dose: 10 units6,7,8,11,12,13,14,16,19,20,21,22,25 Consider using a lower starting dose (such as 0.1 units/kg/day32) especially if 17,19 patient is thin or has a fasting glucose only minimally above goal. -

Use of Inhaled Human Insulin in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Meghan K

Volume X, No. I January/February 2007 Mandy C. Leonard, Pharm.D., BCPS Assistant Director, Drug Information Service Editor Use of Inhaled Human Insulin in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Meghan K. Lehmann, Pharm.D., BCPS by Linda Ghobrial, Pharm.D. Drug Information Specialist Editor I ntroduction: Diabetes mellitus is a concentration >200 mg/dL in the pres- Dana L. Travis, R.Ph. Drug Information Pharmacist metabolic disease characterized by ence of symptoms, or a 2-hour OGTT 2 Editor hyperglycemia and abnormal carbo- value of >200 mg/dL. The diagnosis hydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. is then confirmed by measuring any David A. White, B.S., R.Ph. Diabetes has a very high prevalence one of the three criteria on a subse- Restricted Drug Pharmacist 2 Associate Editor worldwide. There are approximately quent day. 20.8 million (7%) people in the 1 Marcia J. Wyman, Pharm.D. United States who have diabetes. Classification: Most patients with D rug Information Pharmacist Diabetes results from defects in insu- diabetes mellitus are classified as hav- Associate Editor lin secretion, sensitivity, or both. Al- ing either type 1 or type 2. Type 1 Amy T. Sekel, Pharm.D. though the exact cause remains un- diabetes (previously known as juve- D rug Information Pharmacist clear, genetics and environmental fac- nile diabetes) accounts for about 10% IAnss otchiaiste IEsdsituoer tors such as obesity and lack of exer- of all diabetes cases and is usually cise appear to be involved. diagnosed in children and young David Kvancz, M.S., R.Ph., FASHP 2 Chief Pharmacy Officer adults. -

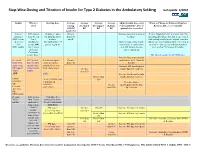

Step-Wise Dosing and Titration of Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes in the Ambulatory Setting Last Update 5/2010

Step -Wise Dosing and Titration of Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes in the Ambulatory Setting last update 5/2010 Insulin When to Starting dose Average Average Average Average Adjust Insulin dose every When to Change to Different Regimen start fasting Pre-lunch Pre-supper Bedtime 3 days until BG < 130, or Recheck A1C every 3 months AM BG BG BG BG optimal dose is reached Goal<130 Lantus A1C greater 10 units or up to Greater Increase dose by 2-4 units at If after 3 months if A1c is greater than 7% (glargine) than 8% on 0.2 units/kg SQ at than 130 bedtime. and optimal bedtime dose has been reached OR Levemir 2 or 3 bedtime mg/dL with fasting blood glucose at goal, consider (detemir) antidiabetic (DC sulfonylurea if Optimal long acting (basal) adding a pre-meal bolus insulin at the largest OR agents OR part of regimen) insulin dose keeps bedtime meal of the day, pre-meal bolus insulin at NPH insulin 1 or 2 agents and AM fasting glucose each meal or 70/30 premix insulin. if Serum values consistent. Creatinine greater than 2 DC all oral agents except Metformin. Increase long acting (basal) Pre-meal A1C greater 2-4 units of rapid Greater insulin dose by 2-4 units at bolus with than 7% with acting or regular than 130 bedtime rapid acting optimal long insulin SQ at each Increase AM rapid/regular OR regular acting (basal) meal (base dose) Greater insulin dose by 2-4 units. insulin insulin. than 130 AND with Increase lunch rapid/regular Greater than insulin dose by 2-4 units. -

Combination Use of Insulin and Incretins in Type 2 Diabetes

Canadian Agency for Agence canadienne Drugs and Technologies des médicaments et des in Health technologies de la santé CADTH Optimal Use Report Volume 3, Issue 1C Combination Use of Insulin and July 2013 Incretins in Type 2 Diabetes Supporting Informed Decisions This report is prepared by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). The report contains a comprehensive review of the existing public literature, studies, materials, and other information and documentation (collectively the “source documentation”) available to CADTH at the time of report preparation. The information in this report is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. The information in this report should not be used as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process, nor is it intended to replace professional medical advice. While CADTH has taken care in the preparation of this document to ensure that its contents are accurate, complete, and up to date as of the date of publication, CADTH does not make any guarantee to that effect. CADTH is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in the source documentation. CADTH is not responsible for any errors or omissions or injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the information in this document or in any of the source documentation. -

Combination Therapies with Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes

Reviews/Commentaries/Position Statements REVIEW ARTICLE Combination Therapies With Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes 1 HANNELE YKI-JA¨RVINEN, MD, FRCP patients who are poorly controlled on oral drugs. One may also predict from these data that if the insulin dose is lowered less than ϳ30% when patients are transferred he U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study lar end points but only on surrogate from insulin alone to insulin combined (UKPDS) demonstrated that inten- markers of risk of micro- and macrovas- with sulfonylurea or metformin, glycemic T sive glucose control with insulin or cular complications, mostly data on gly- control will be better during insulin com- sulfonylureas markedly reduces the risk cemia, body weight, insulin doses, lipids, bination therapy. This is documented by of microvascular complications (1). For and in a few studies, also accurate data on analysis of data from studies in previously myocardial infarction, the reduction in the frequency of hypoglycemias. insulin-treated patients (Table 2). In these comparisons, glycemic control was better risk (16% for a 0.9% decrease in HbA1c) According to a Medline search (1966– was of borderline significance but corre- 2000), insulin alone has been compared in most (19 of 25) comparisons, but the sponded closely to epidemiological pre- with insulin combination therapy in a to- insulin dose was decreased by only 19% dictions (14% decrease for a 1% drop in tal of 34 prospective studies that lasted at in the combination regimens using met- HbA ) (2). These data demonstrated that least 2 months and reported data on HbA formin and by 21% in comparisons using 1c 1 insulin and sulfonylureas (Table 2). -

Guide to Starting and Adjusting Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes*

Guide to Starting and Adjusting Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes* * Adapted from Guide to Starting and Adjusting Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes, ©2008 International Diabetes Center, Minneapolis, MN. All rights reserved. www.cadth.ca Supporting Informed Decisions Many people with type 2 diabetes need insulin therapy. A variety of regimens are available. Here are some tips when discussing insulin therapy:1 • Discuss insulin early to change negative perceptions (e.g., how diabetes changes over time; insulin therapy as a normal part of treatment progression). • To encourage patient buy-in, it may be more strategic initially to begin with a regimen that will be the most acceptable to the patient even if it may not be the clinician’s first choice (e.g., pre-mixed instead of basal-bolus regimen).2 • Provide information on benefits (e.g., more “natural” versus pills, dosing flexibility). • Consider suggesting a “trial” (e.g., for one month). • Compare the relative ease of using newer insulin devices (e.g., pen, smaller needle) versus syringe or vial. • Ensure patient is comfortable with loading and working a pen (or syringe). • Link patient to community support (e.g., Certified Diabetes Educator [CDE] for education on injections and monitoring; nutrition and physical activity counselling). • Show support — ask about and address concerns.2 Consider initiating insulin if…3 • Oral agents alone are not enough to achieve glycemic control or • Presence of symptomatic hyperglycemia with metabolic decompensation or • A1C at diagnosis is > 9%. Timely adjustments -

Tresiba-Product-Monograph.Pdf

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH INCLUDING PATIENT MEDICATION INFORMATION TRESIBA® insulin degludec injection TRESIBA® FlexTouch® 100 U/mL, Solution for injection in a pre-filled pen TRESIBA® FlexTouch® 200 U/mL, Solution for injection in a pre-filled pen Subcutaneous Antidiabetic Agent Long-Acting Basal Insulin Analogue ATC Code: A10AE06 Novo Nordisk Canada Inc. Date of Initial Authorization: AUG 25, 2017 101-2476 Argentia Road Date of Revision: Mississauga, Ontario JUL 23, 2021 Canada L5N 6M1 Submission Control Number: 250276 Product Monograph Master Template Template Date: September 2020 TRESIBA® (insulin degludec injection) Page 1 of 2 RECENT MAJOR LABEL CHANGES 7 Warnings and Precautions 03/2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sections or subsections that are not applicable at the time of authorization are not listed. TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................................2 1 INDICATIONS ..................................................................................................................4 1.1 Pediatrics ................................................................................................................4 1.2 Geriatrics ................................................................................................................4 2 CONTRAINDICATIONS ..................................................................................................4 3 SERIOUS WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS BOX .......................................................4 4 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION -

Study Protocol

CLINICAL TRIAL REPORT ZP4207-17086 (ZEA-DNK-02170) 16.1 TRIAL INFORMATION 16.1.1 PROTOCOL AND PROTOCOL AMENDMENTS This appendix includes Document Date, Version Clinical trial protocol Version 1.0, 08 June 2018 (valid in Slovenia and the USA) Version 3.0, 08 January 2019 (valid in Germany) Section 16.1.1: Protocol and Protocol Amendments Clinical Trial Protocol, final version 1.0 ZP4207-17086 (ZEA-DNK-02170) Clinical Trial Protocol A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-arm trial to assess the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of dasiglucagon relative to placebo and GlucaGen® when administered as a rescue therapy for severe hypoglycemia in children with T1DM treated with insulin Sponsor code: ZP4207-17086 Synteract: ZEA-DNK-02170 EudraCT number: 2018-000892-33 Coordinating investigator: Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Danne Allgemeine Kinderheilkunde Diabetologie, Endokrinologie, Klinische Forschung Diabeteszentrum für Kinder und Jugendliche AUF DER BULT Kinder- und Jugendkrankenhaus Janusz-Korczak-Allee 12 30173 Hannover Germany Sponsor: Zealand Pharma A/S Smedeland 36 2600 Glostrup, Copenhagen Denmark Version: final version 1.0 Date: 08 June 2018 GCP statement This trial will be performed in compliance with Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsinki (with amendments) and local legal and regulatory requirements. 08 June 2018 CONFIDENTIAL Page 1/55 Zealand Pharma A/S ClinicalTrial Prolocol, final ve¡sion 1.0 zP 42A7 -1 7 A 86 (ZEA-DN K-02 1 L Slgnature¡ and agreoment wlth protocot Tltle: phase A 3, ¡andomized, double-blind, placebo- and aclivg-controlled, parallel-arm trial to assess the efficac¡ safety, and pharmacoítinetics of dasiglucagon rela¡ve to placebo and GlucaGeno when edministered as a rescue thêrapy for sevãre triposivcemia ¡n children w¡th TlDM treated with insulin we, the undersigned, agroe to conduct lhls trlal according to lhe Trlal protocol.