Combination Therapies with Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![LANTUS® (Insulin Glargine [Rdna Origin] Injection)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0369/lantus%C2%AE-insulin-glargine-rdna-origin-injection-60369.webp)

LANTUS® (Insulin Glargine [Rdna Origin] Injection)

Rev. March 2007 Rx Only LANTUS® (insulin glargine [rDNA origin] injection) LANTUS® must NOT be diluted or mixed with any other insulin or solution. DESCRIPTION LANTUS® (insulin glargine [rDNA origin] injection) is a sterile solution of insulin glargine for use as an injection. Insulin glargine is a recombinant human insulin analog that is a long-acting (up to 24-hour duration of action), parenteral blood-glucose-lowering agent. (See CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). LANTUS is produced by recombinant DNA technology utilizing a non- pathogenic laboratory strain of Escherichia coli (K12) as the production organism. Insulin glargine differs from human insulin in that the amino acid asparagine at position A21 is replaced by glycine and two arginines are added to the C-terminus of the B-chain. Chemically, it is 21A- B B Gly-30 a-L-Arg-30 b-L-Arg-human insulin and has the empirical formula C267H404N72O78S6 and a molecular weight of 6063. It has the following structural formula: LANTUS consists of insulin glargine dissolved in a clear aqueous fluid. Each milliliter of LANTUS (insulin glargine injection) contains 100 IU (3.6378 mg) insulin glargine. Inactive ingredients for the 10 mL vial are 30 mcg zinc, 2.7 mg m-cresol, 20 mg glycerol 85%, 20 mcg polysorbate 20, and water for injection. Inactive ingredients for the 3 mL cartridge are 30 mcg zinc, 2.7 mg m-cresol, 20 mg glycerol 85%, and water for injection. The pH is adjusted by addition of aqueous solutions of hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. LANTUS has a pH of approximately 4. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action: The primary activity of insulin, including insulin glargine, is regulation of glucose metabolism. -

Comparison of Adjunctive Therapy with Metformin and Acarbose in Patients with Type-1 Diabetes Mellitus

Original Article Comparison of adjunctive therapy with metformin and acarbose in patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus Amir Ziaee1, Neda Esmailzadehha2, Maryam Honardoost3 ABSTRACT Objective: All the aforementioned data have stimulated interest in studying other potential therapies for T1DM including noninsulin pharmacological therapies. The present study attempts to investigate the effect of adjunctive therapy with metformin and acarbose in patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus. Method: In a single-center, placebo-controlled study (IRCT201102165844N1) we compared the results of two clinical trials conducted in two different time periods on 40 patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus. In the first section, metformin was given to the subjects.After six months, metformin was replaced with acarbose in the therapeutic regimen. In both studies, subjects were checked for their BMI, FBS, HbA1C, TGs, Cholesterol, LDL, HDL, 2hpp, unit of NPH and regular insulin variations. Results: Placebo-controlled evaluation of selected factors has showna significant decrease in FBS and TG levels in the metformin group during follow up but acarbose group has shown substantial influence on two hour post prandial (2hpp) and regular insulin intake decline.Moreover, Comparison differences after intervention between two test groups has shown that metformin has had superior impact on FBS and HbA1C decline in patients. Nonetheless, acarbose treatment had noteworthy influence on 2hpp, TGs, Cholesterol, LDL, and regular insulin intake control. Conclusion: The results of this experiment demonstrate that the addition of acarbose or metformin to patients with Type-1 diabetes mellitus who are controlled with insulin is commonly well tolerated and help to improve metabolic control in patients. -

Diabetes Mellitus: Patterns of Pharmaceutical Use in Manitoba

Diabetes Mellitus: Patterns of Pharmaceutical Use in Manitoba by Kim¡ T. G. Guilbert A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Faculty of Pharmacy The University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba @ Kimi T.G. Guilbert, March 2005 TIIE UMYERSITY OF MANITOBA F'ACULTY OF GRADUATE STTJDIES +g+ù+ COPYRIGIIT PERMISSION PAGE Diabetes Mellitus: Patterns of Pharmaceutical Use in Manitoba BY Kimi T.G. Guilbert A ThesisÆracticum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE KIMI T.G. GTIILBERT O2()O5 Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfïlm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfilm Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither this thesis/practicum nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author's written permission. Acknowledgements Upon initiation of this project I had a clear objective in mind--to learn more. As with many endeavors in life that are worthwhile, the path I have followed has brought me many places I did not anticipate at the beginning of my journey. ln reaching the end, it is without a doubt that I did learn more, and the knowledge I have been able to take with me includes a wider spectrum than the topic of population health and medication utilization. -

Type 2 Diabetes Adult Outpatient Insulin Guidelines

Diabetes Coalition of California TYPE 2 DIABETES ADULT OUTPATIENT INSULIN GUIDELINES GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS Start insulin if A1C and glucose levels are above goal despite optimal use of other diabetes 6,7,8 medications. (Consider insulin as initial therapy if A1C very high, such as > 10.0%) 6,7,8 Start with BASAL INSULIN for most patients 1,6 Consider the following goals ADA A1C Goals: A1C < 7.0 for most patients A1C > 7.0 (consider 7.0-7.9) for higher risk patients 1. History of severe hypoglycemia 2. Multiple co-morbid conditions 3. Long standing diabetes 4. Limited life expectancy 5. Advanced complications or 6. Difficult to control despite use of insulin ADA Glucose Goals*: Fasting and premeal glucose < 130 Peak post-meal glucose (1-2 hours after meal) < 180 Difference between premeal and post-meal glucose < 50 *for higher risk patients individualize glucose goals in order to avoid hypoglycemia BASAL INSULIN Intermediate-acting: NPH Note: NPH insulin has elevated risk of hypoglycemia so use with extra caution6,8,15,17,25,32 Long-acting: Glargine (Lantus®) Detemir (Levemir®) 6,7,8 Basal insulin is best starting insulin choice for most patients (if fasting glucose above goal). 6,7 8 Start one of the intermediate-acting or long-acting insulins listed above. Start insulin at night. When starting basal insulin: Continue secretagogues. Continue metformin. 7,8,20,29 Note: if NPH causes nocturnal hypoglycemia, consider switching NPH to long-acting insulin. 17,25,32 STARTING DOSE: Start dose: 10 units6,7,8,11,12,13,14,16,19,20,21,22,25 Consider using a lower starting dose (such as 0.1 units/kg/day32) especially if 17,19 patient is thin or has a fasting glucose only minimally above goal. -

Use of Inhaled Human Insulin in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Meghan K

Volume X, No. I January/February 2007 Mandy C. Leonard, Pharm.D., BCPS Assistant Director, Drug Information Service Editor Use of Inhaled Human Insulin in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Meghan K. Lehmann, Pharm.D., BCPS by Linda Ghobrial, Pharm.D. Drug Information Specialist Editor I ntroduction: Diabetes mellitus is a concentration >200 mg/dL in the pres- Dana L. Travis, R.Ph. Drug Information Pharmacist metabolic disease characterized by ence of symptoms, or a 2-hour OGTT 2 Editor hyperglycemia and abnormal carbo- value of >200 mg/dL. The diagnosis hydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. is then confirmed by measuring any David A. White, B.S., R.Ph. Diabetes has a very high prevalence one of the three criteria on a subse- Restricted Drug Pharmacist 2 Associate Editor worldwide. There are approximately quent day. 20.8 million (7%) people in the 1 Marcia J. Wyman, Pharm.D. United States who have diabetes. Classification: Most patients with D rug Information Pharmacist Diabetes results from defects in insu- diabetes mellitus are classified as hav- Associate Editor lin secretion, sensitivity, or both. Al- ing either type 1 or type 2. Type 1 Amy T. Sekel, Pharm.D. though the exact cause remains un- diabetes (previously known as juve- D rug Information Pharmacist clear, genetics and environmental fac- nile diabetes) accounts for about 10% IAnss otchiaiste IEsdsituoer tors such as obesity and lack of exer- of all diabetes cases and is usually cise appear to be involved. diagnosed in children and young David Kvancz, M.S., R.Ph., FASHP 2 Chief Pharmacy Officer adults. -

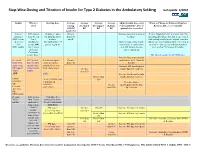

Step-Wise Dosing and Titration of Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes in the Ambulatory Setting Last Update 5/2010

Step -Wise Dosing and Titration of Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes in the Ambulatory Setting last update 5/2010 Insulin When to Starting dose Average Average Average Average Adjust Insulin dose every When to Change to Different Regimen start fasting Pre-lunch Pre-supper Bedtime 3 days until BG < 130, or Recheck A1C every 3 months AM BG BG BG BG optimal dose is reached Goal<130 Lantus A1C greater 10 units or up to Greater Increase dose by 2-4 units at If after 3 months if A1c is greater than 7% (glargine) than 8% on 0.2 units/kg SQ at than 130 bedtime. and optimal bedtime dose has been reached OR Levemir 2 or 3 bedtime mg/dL with fasting blood glucose at goal, consider (detemir) antidiabetic (DC sulfonylurea if Optimal long acting (basal) adding a pre-meal bolus insulin at the largest OR agents OR part of regimen) insulin dose keeps bedtime meal of the day, pre-meal bolus insulin at NPH insulin 1 or 2 agents and AM fasting glucose each meal or 70/30 premix insulin. if Serum values consistent. Creatinine greater than 2 DC all oral agents except Metformin. Increase long acting (basal) Pre-meal A1C greater 2-4 units of rapid Greater insulin dose by 2-4 units at bolus with than 7% with acting or regular than 130 bedtime rapid acting optimal long insulin SQ at each Increase AM rapid/regular OR regular acting (basal) meal (base dose) Greater insulin dose by 2-4 units. insulin insulin. than 130 AND with Increase lunch rapid/regular Greater than insulin dose by 2-4 units. -

Combination Use of Insulin and Incretins in Type 2 Diabetes

Canadian Agency for Agence canadienne Drugs and Technologies des médicaments et des in Health technologies de la santé CADTH Optimal Use Report Volume 3, Issue 1C Combination Use of Insulin and July 2013 Incretins in Type 2 Diabetes Supporting Informed Decisions This report is prepared by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). The report contains a comprehensive review of the existing public literature, studies, materials, and other information and documentation (collectively the “source documentation”) available to CADTH at the time of report preparation. The information in this report is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. The information in this report should not be used as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process, nor is it intended to replace professional medical advice. While CADTH has taken care in the preparation of this document to ensure that its contents are accurate, complete, and up to date as of the date of publication, CADTH does not make any guarantee to that effect. CADTH is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in the source documentation. CADTH is not responsible for any errors or omissions or injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the information in this document or in any of the source documentation. -

Guide to Starting and Adjusting Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes*

Guide to Starting and Adjusting Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes* * Adapted from Guide to Starting and Adjusting Insulin for Type 2 Diabetes, ©2008 International Diabetes Center, Minneapolis, MN. All rights reserved. www.cadth.ca Supporting Informed Decisions Many people with type 2 diabetes need insulin therapy. A variety of regimens are available. Here are some tips when discussing insulin therapy:1 • Discuss insulin early to change negative perceptions (e.g., how diabetes changes over time; insulin therapy as a normal part of treatment progression). • To encourage patient buy-in, it may be more strategic initially to begin with a regimen that will be the most acceptable to the patient even if it may not be the clinician’s first choice (e.g., pre-mixed instead of basal-bolus regimen).2 • Provide information on benefits (e.g., more “natural” versus pills, dosing flexibility). • Consider suggesting a “trial” (e.g., for one month). • Compare the relative ease of using newer insulin devices (e.g., pen, smaller needle) versus syringe or vial. • Ensure patient is comfortable with loading and working a pen (or syringe). • Link patient to community support (e.g., Certified Diabetes Educator [CDE] for education on injections and monitoring; nutrition and physical activity counselling). • Show support — ask about and address concerns.2 Consider initiating insulin if…3 • Oral agents alone are not enough to achieve glycemic control or • Presence of symptomatic hyperglycemia with metabolic decompensation or • A1C at diagnosis is > 9%. Timely adjustments -

Inpatient Care | Lantus (Insulin Glargine Injection) 100 Units/Ml

For noncritically ill hospitalized patients with diabetes Lantus® as part of a basal-prandial dosing regimen ARA basal-prandialBBIT 2 BASAL-PRA dosing NDoptionIAL forDOS nonintensiveING care inpatients with type 2 diabetes from the RABBIT 2 Study1,a A basal-prandial dosing option for inpatients with type 2 diabetes from the RABBIT 2 Study 31 Calculate total daily dose based Total daily dose on BG and weight at the time of • For BG 140-200 mg/dL, use 0.4 Units/kg admission • For BG 201-400 mg/dL, use 0.5 Units/kg Dose administration Divide the calculated dose into basal and prandial components • Administer 50% of daily dose as basal insulin • Administer the other 50% as rapid-acting prandial 50:50 insulin divided into 3 mealtime injections basal prandial Dose administration Monitor BG, add supplemental • If fasting or mean BG during the day >140 mg/dL, increase basal insulin dose by 20% rapid-acting insulin, and adjust doses as needed • If fasting and premeal BG >140 mg/dL, add supplemental rapid-acting insulin • If BG <70 mg/dL, reduce basal insulin dose by 20% • Hold prandial insulin doses in patients not eating RABBIT 2 was a multicenter, prospective, open-label, randomized study (N=130) to compare the efficacy of a basal-prandial regimen of insulin glargine + insulin glulisine with SSI monotherapy (regular human insulin) in insulin-naive nonsurgical patients aged 18 to 80 years with type 2 diabetes. Patients in the basal-prandial group received glargine once daily and glulisine before meals. SSI was given 4 times per Aday basal-prandialfor BG >140 mg/dL. -

Canagliflozin Lowers Postprandial Glucose and Insulin by Delaying

Clinical Care/Education/Nutrition/Psychosocial Research ORIGINAL ARTICLE Canagliflozin Lowers Postprandial Glucose and Insulin by Delaying Intestinal Glucose Absorption in Addition to Increasing Urinary Glucose Excretion Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study 1 2 DAVID POLIDORI, PHD NICOLE VACCARO, BS low-capacity, high-affinity transporter ex- 2 2 SUE SHA, MD, PHD KRISTIN FARRELL, BS 3 2 pressed in the distal segment of the prox- SUNDER MUDALIAR, MD PAUL ROTHENBERG, MD, PHD 3 3 imal tubule (1), in the intestinal mucosa THEODORE P. CIARALDI, PHD ROBERT R. HENRY, MD 2 of the small intestine (2), and in other tis- ATALANTA GHOSH, PHD sues to a lesser extent (3). Although SGLT1 plays a smaller role in renal glu- cose absorption than SGLT2, SGLT1 is OBJECTIVEdCanagliflozin, a sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, is also a low-potency SGLT1 inhibitor. This study tested the hypothesis that intestinal canagliflozin levels the primary pathway involved in intesti- postdose are sufficiently high to transiently inhibit intestinal SGLT1, thereby delaying intestinal nal glucose and galactose absorption glucose absorption. (2,4,5). Pharmacologic inhibition of SGLT2 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODSdThis two-period, crossover study evaluated is a novel approach to lowering plasma fl effects of canagli ozin on intestinal glucose absorption in 20 healthy subjects using a dual-tracer glucose in hyperglycemic individuals by method. Placebo or canagliflozin 300 mg was given 20 min before a 600-kcal mixed-meal tolerance test. Plasma glucose, 3H-glucose, 14C-glucose, and insulin were measured frequently blocking renal glucose reabsorption, low- ering the renal threshold for glucose for 6 h to calculate rates of appearance of oral glucose (RaO) in plasma, endogenous glucose production, and glucose disposal. -

Preferred Drug List Drug Class Review Announcement

PDL Drug Class Review Announcement July 13, 2021 Drug Classes to be reviewed: Anticonvulsants, Oral; Stimulants and other ADHD Agents; Bone Resorption Suppression & Related Agents; Contraceptives (Oral & Topical); Estrogen Agents (Injectable, Oral/Transdermal); Diabetes Management Agents (Amylin, Biguanides, DPP-4 Inhibitors, GLP-1 Analogues, Hypoglycemic Combinations, Insulins, Meglitinides, SGLT-2 Inhibitors, Thiazolidinediones); Glucagon, Self-Administered; GI Motility (Chronic); Anticoagulants (Oral & Parenteral); Antiplatelet Agents; Colony Stimulating Factors; Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agents; Newer Hereditary Angioedema Agents; Ophthalmic Immunomodulators; Overactive Bladder Agents, and Prenatal Vitamins. These drug classes will be reviewed at the July 13th, 2021 P&T Committee meeting from 1-5pm. The meeting will be held virtually. Dossiers and Supplemental Rebate offers are due to Magellan by June 15, 2021. Interested parties who want to present at the meeting shall give advanced notice and provide a one-page summary of the clinical information that will be presented for P&T Committee dissemination. Please contact Jessica Czechowski, Pharmacist Account Executive, [email protected] and carbon copy Brittany Schock, PDL & Clinical Strategy Pharmacist, at 303-866-6371 or by email at [email protected] to give advance notice to present at the meeting. Advance notice requests to present and/or written public comments can be submitted to and will be distributed to P&T Committee Members, once approved. Please provide -

Insulin Pocketcard™

Insulin PocketCard™ Effective Action Insulin Name Onset Peak Duration Considerations Aspart (Novolog) Rapid Acting Lispro (Humalog) 5 - 15 min 30 - 90 min < 5 hrs Bolus insulin Analogs lowers after-meal Glulisine (Apidra) Bolus glucose. Post meal Regular 30 - 60 min 2 - 3 hrs 5 - 8 hrs BG reflects efficacy. Short Acting Concentrated Regular Insulin Basal insulin 30 - 60 min 2 - 3 hrs Up to 24 hrs 500 units/mL reg insulin “U-500” controls BG between meals and nighttime. Intermediate NPH 2 - 4 hrs 4 - 10 hrs 10 - 16 hrs Fasting BG reflects Detemir (Levemir) 3 - 8 hrs No peak 6 - 24 hrs efficacy. Basal Glargine (Lantus) 2 - 4 hrs No peak 20 - 24 hrs Side effects: Long Acting hypoglycemia, Concentrated Glargine (Toujeo) 6 hrs No Peak 24 hrs 300 units/mL in 1.5 mL Pen weight gain. Combo of NPH + Reg Typical dosing Intermediate 70/30 = 70% NPH + 30% Reg 30 - 60 min range: 0.5-1.0 units/ + short Basal 50/50 = 50% NPH + 50% Reg kg body wt/day. Dis- + Dual peaks 10 - 16 hrs card opened insulin Bolus Intermediate Novolog® Mix - 70/30 vials after 28 days. 5 - 15 min + rapid Humalog® Mix - 75/25 or 50/50 Insulin action times can vary with each injection, time periods listed here are general guidelines only; please consult prescribing information for details. REV 03/2015 © 2015 A Diabetes PocketCard™ Inhaled Insulin from Diabetes Education Services | DiabetesEd.Net Action Insulin Name Dose Range Onset Peak Duration Considerations Assess lung function before starting. Afrezza Inhaled 4 and 8 unit Avoid in chronic lung disease — Bolus – regular human cartridges 15 mins 1 hr 3 hrs acute .