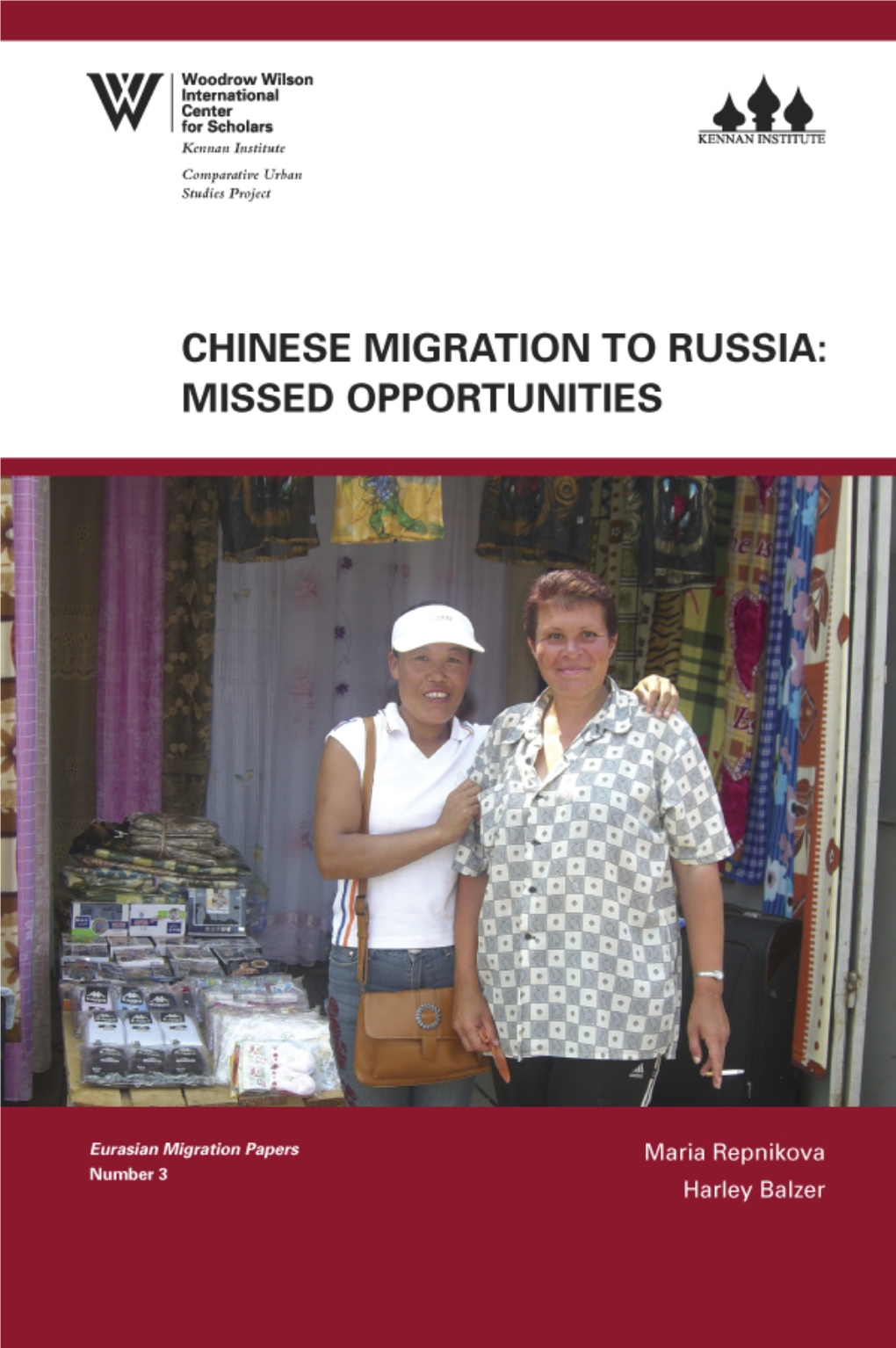

Chinese Migration to Russia: Missed Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leisure in Russia: 'Free' Time and Its Uses

123 ARTICLES Stephen Lovell Leisure in Russia: ‘Free’ Time and Its Uses In his now celebrated memoir of the Russian factory workers life at the turn of the nineteenth century, Semen Kanatchikov recalls a story that was found to be especially hilarious by his artel1 mates in Moscow. It concerns a lazy worker, living some two hundred miles from the place where we fools live, who is sent out by a priest, apparently his master, to plough a distant field. The worker successfully puts off his departure, asking to be allowed to eat lunch first so that he can work all the day through. On finishing that meal, he reuses the same argument and gains permission from the priest to proceed directly to supper. After stuffing his belly even fuller, he makes his bed and lies down to sleep. When challenged by the priest, he makes an unanswer- able reply: Work after supper? Why, everyone goes to bed after supper! [Kanatchikov 1986: 1213]. Stephen Lovell An audience of peasants-turned-proletarians had King’s College, University of London obvious reasons for finding this tale amusing. 1 An artel is a kind of grassroots cooperative society organised by peasants and peasant in migrants to cities to provide, for example, accommodation and catering facilities, and general support. [Editor]. No.3 FORUM FOR ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURE 124 The figure of the master conflates three disliked embodiments of authority: the priest, the landlord and the factory owner. In addition, the joke can be read as a variation on the eternal theme of what happens when low peasant cunning has the good fortune to encoun- ter rule-bound dull-wittedness. -

Changchun–Harbin Expressway Project

Performance Evaluation Report Project Number: PPE : PRC 30389 Loan Numbers: 1641/1642 December 2006 People’s Republic of China: Changchun–Harbin Expressway Project Operations Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) At Appraisal At Project Completion At Operations Evaluation (July 1998) (August 2004) (December 2006) CNY1.00 = $0.1208 $0.1232 $0.1277 $1.00 = CNY8.28 CNY8.12 CNY7.83 ABBREVIATIONS AADT – annual average daily traffic ADB – Asian Development Bank CDB – China Development Bank DMF – design and monitoring framework EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return GDP – gross domestic product ha – hectare HHEC – Heilongjiang Hashuang Expressway Corporation HPCD – Heilongjiang Provincial Communications Department ICB – international competitive bidding JPCD – Jilin Provincial Communications Department JPEC – Jilin Provincial Expressway Corporation MOC – Ministry of Communications NTHS – national trunk highway system O&M – operations and maintenance OEM – Operations Evaluation Mission PCD – provincial communication department PCR – project completion report PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance PRC – People’s Republic of China RRP – report and recommendation of the President TA – technical assistance VOC – vehicle operating cost NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Keywords asian development bank, development effectiveness, expressways, people’s republic of china, performance evaluation, heilongjiang province, jilin province, transport Director Ramesh Adhikari, Operations Evaluation Division 2, OED Team leader Marco Gatti, Senior Evaluation Specialist, OED Team members Vivien Buhat-Ramos, Evaluation Officer, OED Anna Silverio, Operations Evaluation Assistant, OED Irene Garganta, Operations Evaluation Assistant, OED Operations Evaluation Department, PE-696 CONTENTS Page BASIC DATA v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii MAPS xi I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. -

Optimization Path of the Freight Channel of Heilongjiang Province

2017 3rd International Conference on Education and Social Development (ICESD 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-444-8 Optimization Path of the Freight Channel of Heilongjiang Province to Russia 1,a,* 2,b Jin-Ping ZHANG , Jia-Yi YUAN 1Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China 2International Department of Harbin No.9 High School, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China [email protected], [email protected] * Corresponding author Keywords: Heilongjiang Province, Russia, Freight Channel, Optimization Path. Abstract. Heilongjiang Province becomes the most important province for China's import and export trade to Russia due to its unique geographical advantages and strong complementary between industry and product structure. However, the existing problems in the trade freight channel layout and traffic capacity restrict the bilateral trade scale expansion and trade efficiency improvement. Therefore, the government should engage in rational distribution of cross-border trade channel, strengthen infrastructure construction in the border port cities and node cities, and improve the software support and the quality of service on the basis of full communication and coordination with the relevant Russian government, which may contribute to upgrade bilateral economic and trade cooperation. Introduction Heilongjiang Province is irreplaceable in China's trade with Russia because of its geographical advantages, a long history of economic and trade cooperation, and complementary in industry and product structures. Its total value of import and export trade to Russia account for more than 2/3 of the whole provinces and nearly 1/4 of that of China. After years of efforts, there exist both improvement in channel infrastructure, layout and docking and problems in channel size, functional positioning and layout, as well as important node construction which do not match with cross-border freight development. -

Ambiguous Attachments and Industrious Nostalgias Heritage

Ambiguous Attachments and Industrious Nostalgias Heritage Narratives of Russian Old Believers in Romania Cristina Clopot Abstract: This article questions notions of belonging in the case of displaced communities’ descendants and discusses such groups’ efforts to preserve their heritage. It examines the instrumental use of nostalgia in heritage discourses that drive preservation efforts. The case study presented is focused on the Russian Old Believers in Romania. Their creativity in reforming heritage practices is considered in relation to heritage discourses that emphasise continuity. The ethnographic data presented in this article, derived from my doctoral research project, is focused on three major themes: language preservation, the singing tradition and the use of heritage for touristic purposes. Keywords: belonging, heritage, narratives, nostalgia, Romania, Russian Old Believers It was during a hot summer day in 2015 when, together with a group of informants, I visited a Russian Old Believers’ church in Climăuți, a Romanian village situated at the border with Ukraine (Figure 1).1 After attending a church service, our hosts proposed to visit a monument, an Old Believers’ cross situated a couple of kilometres away from the village. This ten-metre tall marble monument erected in memory of the forefathers, represents the connection with the past for Old Believers (Figure 2). At the base of the monument the following text is written in Russian: ‘Honour and glory to our Starovery Russian ancestors that settled in these places in defence of their Ancient orthodox faith’ (my translation). The text points to a precious memory central for the heritage narratives of Old Believers in Romania today that will be discussed in this essay. -

Estimations of Undisturbed Ground Temperatures Using Numerical and Analytical Modeling

ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING By LU XING Bachelor of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Huazhong University of Science & Technology Wuhan, China 2008 Master of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK, US 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2014 ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING Dissertation Approved: Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler Dissertation Adviser Dr. Daniel E. Fisher Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar Dr. Richard A. Beier ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler, who patiently guided me through the hard times and encouraged me to continue in every stage of this study until it was completed. I greatly appreciate all his efforts in making me a more qualified PhD, an independent researcher, a stronger and better person. Also, I would like to devote my sincere thanks to my parents, Hongda Xing and Chune Mei, who have been with me all the time. Their endless support, unconditional love and patience are the biggest reason for all the successes in my life. To all my good friends, colleagues in the US and in China, who talked to me and were with me during the difficult times. I would like to give many thanks to my committee members, Dr. Daniel E. Fisher, Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar and Dr. Richard A. Beier for their suggestions which helped me to improve my research and dissertation. -

Phenomenon of Diaspora in the Preservation of National Culture on Example of Russian Diaspora in Bolivia

PHENOMENON OF DIASPORA IN THE PRESERVATION OF NATIONAL CULTURE ON EXAMPLE OF RUSSIAN DIASPORA IN BOLIVIA Elena Serukhina1 1Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Airlangga University Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The development of the modern world is characterized, as we know, by globalization. Can the phenomenon of the diaspora in modern social life be associated with it? No, because the diaspora is directly connected with culture, while globalization is opposed to culture. Globalization is aimed at unification, ignoring the problem of cultural identity. Globalization involves the erasure of cultural features, the loss of cultural, ethnic, religious differences. But at the same time, globalization contributes to the growth of population migration, which leads to an increase in the number of diasporas abroad. The rapid growth of immigrant communities and their institutionalization forced to talk about "the diasporaization of the world" as one of the scenarios for the development of mankind. One way or another, this process deepens and takes more and more new forms, and the role of diasporas and their influence are intensified. In this article the author explores how the diaspora, being the product of globalization, nevertheless contributes to the preservation and development of national culture. Every year, the number of diasporas increases following the migration of the population, so the study of the diaspora's topic is now more relevant than ever. Data collection techniques used in this study is a library study, which literature study itself is looking for data that support for research. The author, citing the example of the Russian Diaspora in Bolivia, comes to the conclusion that the diaspora, as one of the global phenomena of the present, contributes to the preservation and revival of the national culture. -

A Brief Introduction to the Dairy Industry in Heilongjiang NBSO Dalian

A brief introduction to the Dairy Industry in Heilongjiang NBSO Dalian RVO.nl | Brief Introduction Dairy industry Heilongjiang, NBSO Dalian Colofon This is a publication of: Netherlands Enterprise Agency Prinses Beatrixlaan 2 PO Box 93144, 2509 AC, The Hague Phone: 088 042 42 42 Email: via contact form on the website Website: www.rvo.nl This survey has been conducted by the Netherlands Business Support Office in Dalian If you have any questions regarding this business sector in Heilongjiang Province or need any form of business support, please contact NBSO Dalian: Chief Representative: Renée Derks Deputy Representative: Yin Hang Phone: +86 (0)411 3986 9998 Email: [email protected] For further information on the Netherlands Business Support Offices, see www.nbso.nl © Netherlands Enterprise Agency, August 2015 NL Enterprise Agency is a department of the Dutch ministry of Economic Affairs that implements government policy for agricultural, sustainability, innovation, and international business and cooperation. NL Enterprise Agency is the contact point for businesses, educational institutions and government bodies for information and advice, financing, networking and regulatory matters. Although a great degree of care has been taken in the preparation of this document, no rights may be derived from this brochure, or from any of the examples contained herein, nor may NL Enterprise Agency be held liable for the consequences arising from the use thereof. This publication may not be reproduced, in whole, or in part, in any form, without the prior written consent of the publisher. Page 2 of 10 RVO.nl | Brief Introduction Dairy industry Heilongjiang, NBSO Dalian Contents Colofon ..................................................................................................... -

Difference in Media Representation of Immigrants and Immigration in France and Russia

Difference in media representation of immigrants and immigration in France and Russia By Evgeniia Kholmanskikh Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Marina Popescu Word Count: 13,567 Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2015 Abstract This thesis studies the differences in media coverage of immigrants in Russia and France. Its objective is to determine whether the media in different countries portray immigrants differently and to provide insights about the underlying reasons. I accomplish the analysis by a means of content analysis of a range of articles published in representative French and Russian periodic press between April 2014 and April 2015. In total, the newspapers chosen for the analysis provided more than 950 references about the immigrants over the indicated period. The main result is that French media representation of immigrants is more homogenous and more positive than Russian. The more homogenous representation is rather surprising conclusion taking into account a more diversified media ownership and less censorship in France. A partial explanation of this phenomenon longer history of the public discussion on the immigration-related problems, which leads to the formation of the prevailing point of view in a society. The more positive representation of immigrants in France may be due to subtle press dependency on the government reinforced by the recent violent clashes and terrorist attacks involving immigrants. As a result, the French government, in pursue of promoting a more tolerant attitude in the society toward immigrants, can skew the representation of immigrants to a more positive side through indirect influence on the media. -

Claiming the Diaspora: Russia's Compatriot Policy

Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe Vol 15, No 3, 2016, 1-25. Copyright © ECMI 2016 This article is located at: http://www.ecmi.de/fileadmin/downloads/publications/JEMIE/201 6/Kallas.pdf Claiming the diaspora: Russia’s compatriot policy and its reception by Estonian-Russian population Kristina Kallas Tartu University Abstract Nearly a decade ago Russia took a turn from declarative compatriot protection discourse to a more programmatic approach consolidating large Russophone 1 populations abroad and connecting them more with Russia by employing the newly emerged concept of Russkiy Mir as a unifying factor for Russophones around the world. Most academic debates have since focused on analyzing Russkiy Mir as Russia’s soft power tool. This article looks at Russia’s compatriot policy from the perspective of the claimed compatriot populations themselves. It is a single empirical in-depth case study of Russia’s compatriot policy and its reception by the Russian-speaking community in Estonia. The focus is on Russia’s claims on the Russophone population of Estonia and the reactions and perceptions of Russia’s ambitions by the Estonian-Russians themselves. Keywords: compatriots, Russian diaspora, diasporisation, integration in Estonia, identity of Russian-speakers Introduction Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military intervention in Eastern Ukraine in 2014 dozens of journalists have ventured to Narva, the easternmost town of Estonia, with one question on their mind: “Is Narva next?” As one article in The Diplomat Publisher put it, The author is a director of Tartu University Narva College and a PhD candidate at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies, Lai 36, Tartu, Estonia. -

Exporting Unemployment: Migration As Lens to Understand Relations Between Russia, China, and Central Asia

Exporting Unemployment: Migration as Lens to Understand Relations between Russia, China, and Central Asia M.A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joseph M Castleton, B.A. Graduate Program in Slavic and East European Studies The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Morgan Liu, Advisor Goldie Shabad Copyright by Joseph M Castleton 2010 Abstract The post-Soviet triangle of relations between Russia, China, and Central Asia is an important but underappreciated relationship, and is the focus of this paper. The formation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001, comprising Russia, China, and Central Asia, was regarded by many in the West as a bloc similar to the Warsaw Pact. In reality, the creation of the group symbolizes a relationship more locally invested and more geared toward balancing conflicting national interests in the region than with competing against the West. The SCO, however, cannot alone explain the complexities of Russia, China, and Central Asia’s relationship. The triangle is a culmination of bilateral dealings over national and regional interests. The real work is not accomplished via multilateral forums like the SCO, but rather through bilateral interaction. Understanding the shared and conflicting interests of these nations can shed light on various factors influencing policy at the national and regional level. One key to understanding these influences is looking at Russia, China, and Central Asia’s relationship through the lens of migration. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia quickly became the second most popular destination for immigrants in the world behind the United States. -

Vision for the Northeast Asia Transportation Corridors

Northeast Asia Economic Conference Organizing Committee Transportation Subcommittee Chairman KAYAHARA, Hideo Japan: Director General, the Japan Port and Harbor Association/ Counselor, ERINA Committee Members DAI, Xiyao PRC: Director, Tumen River Area Development Administration, the People’ s Government of Jilin Province WANG, Shengjin PRC: Dean, Northeast Asia Studies College of Jilin University TSENGEL, Tsegmidyn Mongolia: State Secretary, Ministry of Infrastructure SEMENIKHIN, Yaroslav RF: President, Far Eastern Marine Research, Design and Technology Institute (FEMRI) Byung-Min AHN ROK: Head, Northeast Asia Research Team, Korea Transportation Institute(KOTI) GOMBO, Tsogtsaikhan UN: Deputy Director, Tumen Secretariat, UNDP Secretariat ERINA (Ikuo MITSUHASHI, Senior Fellow, Kazumi KAWAMURA, Researcher, Research Division, Dmiriy L. Sergachev, Researcher, Research Division) Vision for the Northeast Asia Transportation Corridors Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Nine Transportation Corridors in Northeast Asia.................................... 2 Chapter 3 Current Situation and Problems of the Nine Transportation Corridors in Northeast Asia ....................................................................................... 5 3.1 Taishet~Vanino Transportation Corridor 3.2 Siberian Land Bridge (SLB) Transportation Corridor 3.3 Suifenhe Transportation Corridor 3.4 Tumen River Transportation Corridor 3.5 Dalian Transportation Corridor -

The Russian Diaspora: a Result of Transit Migrations Or Part of Russia

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1016-1044 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 The Russian diaspora: a result of transit migrations or part of Russia Svetlana G. Maximova1 1Altai State University, Barnaul, Russian Federation [email protected] Oksana E. Noyanzina2 2Altai State University, Barnaul, Russian Federation [email protected] Daria A. Omelchenko3 3Altai State University, Barnaul, Russian Federation [email protected] Irina N. Molodikova4 4 Central European University, Budapest, Hungary [email protected] Alla V. Kovaleva5 5Altai State University, Barnaul, Russian Federation [email protected] Abstract The goal of the article is to evaluate the number of the Russian diaspora and its dispersion all over the world, such as the Russian- speaking community, explore its qualitative characteristics, language behavior and attitudes to the inclusion into the Russian World through descriptive research methods. As a result, the Russian diaspora refuses to see attractive and perspective social, educational, economic, and tourist opportunities of Russia and feel positive or neutral to the Russian language and culture. As a conclusion, the Russian diaspora has a great potential of collaboration and bases policy in relation to comrades as extremely important. Key words: Russian Diaspora, Communities, Migration, Transit. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1017 Maximova et al. Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1016-1044 La diáspora rusa: un resultado de migraciones de tránsito o parte de Rusia Resumen El objetivo del artículo es evaluar el número de la diáspora rusa y su dispersión en todo el mundo, como la comunidad de habla rusa, explorar sus características cualitativas, el comportamiento del idioma y las actitudes hacia la inclusión en el mundo ruso a través de métodos de investigación descriptivos.