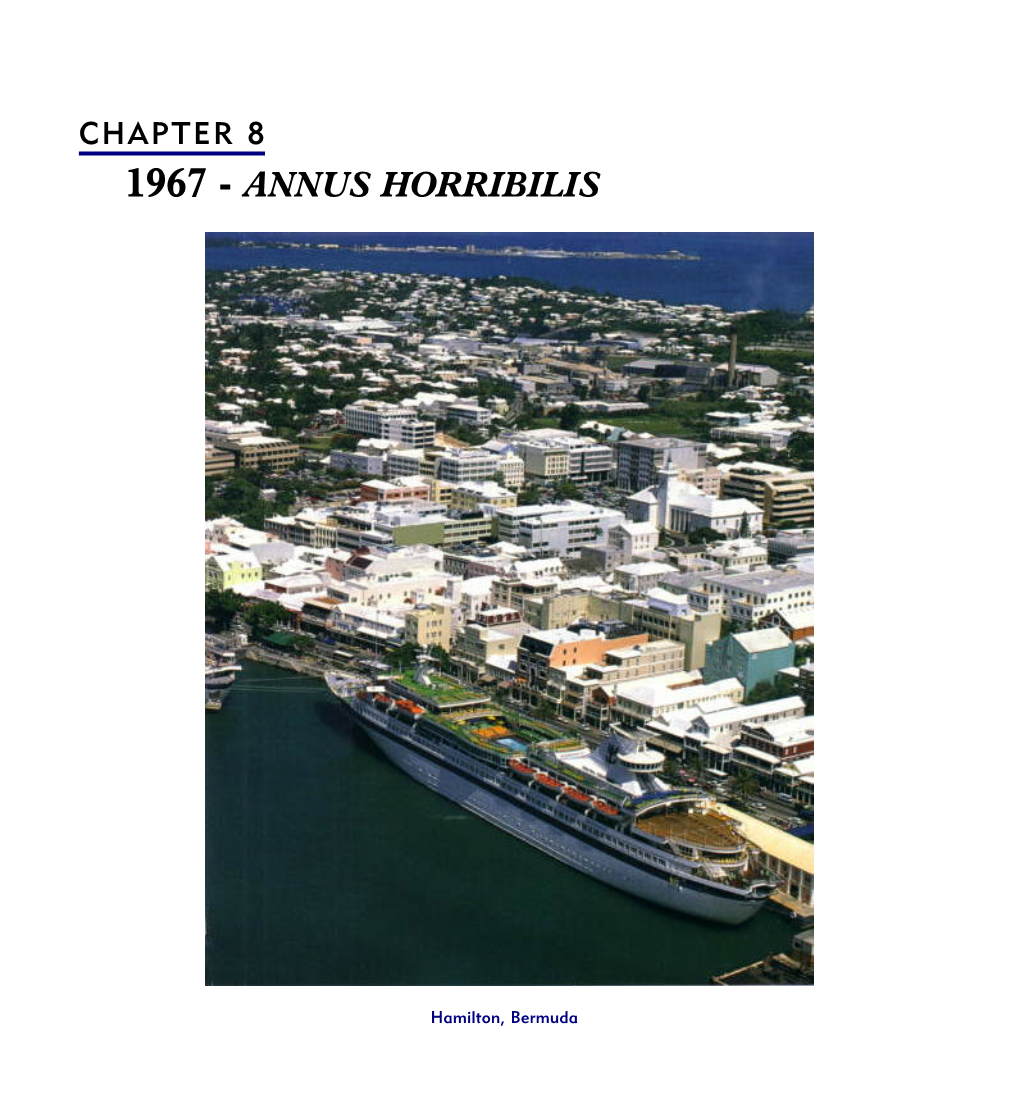

Chapter 8 1967 - Annus Horribilis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Colonic Propionate Delivery a Novel Solution to Improve Metabolism and Inflammation in Overweight Or Obese Subjects?

Commentary in IgG levels in IPE-treated subjects versus Is colonic propionate delivery a novel those receiving cellulose supplementa- tion. This interesting discovery is the Gut: first published as 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318776 on 26 April 2019. Downloaded from solution to improve metabolism and first evidence in humans that promoting the delivery of propionate in the colon inflammation in overweight or may affect adaptive immunity. It is worth noting that previous preclinical and clin- obese subjects? ical data have shown that supplementation with inulin-type fructans was associated 1,2 with a lower inflammatory tone and a Patrice D Cani reinforcement of the gut barrier.7 8 Never- theless, it remains unknown if these effects Increased intake of dietary fibre has been was the lack of evidence that the observed are directly linked with the production of linked to beneficial impacts on health for effects were due to the presence of inulin propionate, changes in the proportion of decades. Strikingly, the exact mechanisms itself on IPE or the delivery of propionate the overall levels of SCFAs, or the pres- of action are not yet fully understood. into the colon. ence of any other bacterial metabolites. Among the different families of fibres, In GUT, Chambers and colleagues Alongside the changes in the levels prebiotics have gained attention mainly addressed this gap of knowledge and of SCFAs, plasma metabolome analysis because of their capacity to selectively expanded on their previous findings.6 For revealed that each of the supplementa- modulate the gut microbiota composition 42 days, they investigated the impact of tion periods was correlated with different 1 and promote health benefits. -

The Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST) Transition

Copyright by David Samuel Simmons 2009 The Dissertation Committee for David Samuel Simmons certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Phase and Conformational Behavior of LCST-Driven Stimuli Responsive Polymers Committee: ______________________________ Isaac Sanchez, Supervisor ______________________________ Nicholas Peppas ______________________________ Krishnendu Roy ______________________________ Venkat Ganesan ______________________________ Thomas Truskett Phase and Conformational Behavior of LCST-Driven Stimuli Responsive Polymers by David Samuel Simmons, B.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2009 To my grandfather, who made me an engineer before I knew the word and to my wife, Carey, for being my partner on my good days and bad. Acknowledgements I am extraordinarily fortunate in the support I have received on the path to this accomplishment. My adviser, Dr. Isaac Sanchez, has made this publication possible with his advice, support, and willingness to field my ideas at random times in the afternoon; he has my deep appreciation for his outstanding guidance. My thanks also go to the members of my Ph.D. committee for their valuable feedback in improving my research and exploring new directions. I am likewise grateful to the other members of Dr. Sanchez’ research group – Xiaoyan Wang, Yingying Jiang, Xiaochu Wang, and Frank Willmore – who have shared their ideas and provided valuable sounding boards for my mine. I would particularly like to express appreciation for Frank’s donation of his own post-graduation time in assisting my research. -

Exercise and Cellular Respiration Lab

California State University of Bakersfield, Department of Chemistry Exercise and Cellular Respiration Lab Standards: MS-LS1-7 Develop a model to describe how food is rearranged through chemical reactions forming new molecules that support growth and/or release energy as this matter moves through an organism. Introduction: I. Background Information. Cellular respiration (see chemical reaction below) is a chemical reaction that occurs in your cells to create energy; when you are exercising your muscle cells are creating ATP to contract. Cellular respiration requires oxygen (which is breathed in) and creates carbon dioxide (which is breathed out). This lab will address how exercise (increased muscle activity) affects the rate of cellular respiration. You will measure 3 different indicators of cellular respiration: breathing rate, heart rate, and carbon dioxide production. You will measure these indicators at rest (with no exercise) and after 1 and 2 minutes of exercise. Breathing rate is measured in breaths per minute, heart rate in beats per minute, and carbon dioxide in the time it takes bromothymol blue to change color. Carbon dioxide production can be measured by breathing through a straw into a solution of bromothymol blue (BTB). BTB is an acid indicator; when it reacts with acid it turns from blue to yellow. When carbon dioxide reacts with water, a weak acid (carbonic acid) is formed (see chemical reaction below). The more carbon dioxide you breathe into the BTB solution, the faster it will change color to yellow. The purpose of this lab activity is to analyze the effect of exercise on cellular respiration. Background: I. -

Brownie's THIRD LUNG

BrMARINEownie GROUP’s Owner’s Manual Variable Speed Hand Carry Hookah Diving System ADVENTURE IS ALWAYS ON THE LINE! VSHCDC Systems This manual is also available online 3001 NW 25th Avenue, Pompano Beach, FL 33069 USA Ph +1.954.462.5570 Fx +1.954.462.6115 www.BrowniesMarineGroup.com CONGRATULATIONS ON YOUR PURCHASE OF A BROWNIE’S SYSTEM You now have in your possession the finest, most reliable, surface supplied breathing air system available. The operation is designed with your safety and convenience in mind, and by carefully reading this brief manual you can be assured of many hours of trouble-free enjoyment. READ ALL SAFETY RULES AND OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS CONTAINED IN THIS MANUAL AND FOLLOW THEM WITH EACH USE OF THIS PRODUCT. MANUAL SAFETY NOTICES Important instructions concerning the endangerment of personnel, technical safety or operator safety will be specially emphasized in this manual by placing the information in the following types of safety notices. DANGER DANGER INDICATES AN IMMINENTLY HAZARDOUS SITUATION WHICH, IF NOT AVOIDED, WILL RESULT IN DEATH OR SERIOUS INJURY. THIS IS LIMITED TO THE MOST EXTREME SITUATIONS. WARNING WARNING INDICATES A POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS SITUATION WHICH, IF NOT AVOIDED, COULD RESULT IN DEATH OR INJURY. CAUTION CAUTION INDICATES A POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS SITUATION WHICH, IF NOT AVOIDED, MAY RESULT IN MINOR OR MODERATE INJURY. IT MAY ALSO BE USED TO ALERT AGAINST UNSAFE PRACTICES. NOTE NOTE ADVISE OF TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS THAT REQUIRE PARTICULAR ATTENTION BY THE OPERATOR OR THE MAINTENANCE TECHNICIAN FOR PROPER MAINTENANCE AND UTILIZATION OF THE EQUIPMENT. REGISTER YOUR PRODUCT ONLINE Go to www.BrowniesMarineGroup.com to register your product. -

Affinity of Small-Molecule Solutes to Hydrophobic, Hydrophilic, and Chemically Patterned Interfaces in Aqueous Solution

Affinity of small-molecule solutes to hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and chemically patterned interfaces in aqueous solution Jacob I. Monroea, Sally Jiaoa, R. Justin Davisb, Dennis Robinson Browna, Lynn E. Katzb, and M. Scott Shella,1 aDepartment of Chemical Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106; and bDepartment of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712 Edited by Peter J. Rossky, Rice University, Houston, TX, and approved November 17, 2020 (received for review September 30, 2020) Performance of membranes for water purification is highly influ- However, a molecular understanding that links membrane enced by the interactions of solvated species with membrane surface chemistry to solute affinity and hence membrane func- surfaces, including surface adsorption of solutes upon fouling. tional properties remains incomplete, due in part to the complex Current efforts toward fouling-resistant membranes often pursue interplay among specific interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, surface hydrophilization, frequently motivated by macroscopic electrostatics, dispersion) and molecular morphology (e.g., sur- measures of hydrophilicity, because hydrophobicity is thought to face and polymer configurations) that are difficult to disentangle increase solute–surface affinity. While this heuristic has driven di- (11–14). Chemically heterogeneous surfaces are even less un- verse membrane functionalization strategies, here we build on derstood but can affect fouling in complex ways. -

The Hydrophobic Effect Oil and Water Do Not Mix. This Fact Is So Well

The hydrophobic effect Oil and water do not mix. This fact is so well engrained in our ever-day experience that we never ask “why”. Well, today we are going to ask just this question: “why do oil and water not mix?” At the end of the class you will hopefully see that the reason oil and water do not mix is quite distinct from the reason many other substance do not mix. You will also see that the hydrophobic effect is part of a family of processes called “entropy driven ordering” and that the hydrophobic effect has nothing to do with bonds between hydrophobic molecules. This should sound a bit strange to you right now, but I am sure that at the end of the class it will all make sense to you. Why most liquids mix or do not mix (the generic case) What would our physico-chemical intuition tell us about the process of mixing two liquids? Lets think of a simple lattice model for the two solutions. If we call the substances A and B, the energy for mixing should then be the energy of interaction that are made between A and B, minus the energy of interactions that A made with A, and B made with B, plus the entropy of mixing. "Gmixing = "Hmixing # T"Smixing where "Hmixing = 2"Ha#b # "Ha#a # "Hb#b What predictions would this simple model for solutions make for the energetics of mixing? First, mixing should be favored by entropy and therefore the tendency to mix ! should increase with temperature. -

Ph Temperature Compensation

pH Temperature Compensation There are two types of temperature compensation when discussing pH measurements. Automatic Temperature Compensation (ATC), which compensates for the varying milli-volt output from the electrode due to temperature changes of the process solution and Solution Temperature Compensation (STC), which corrects for a change in the chemistry (change in pH) of the solution as the temperature of the solution changes. Automatic Temperature Compensation In a pH-measuring loop, there are three main components. The glass (pH) measuring electrode, the reference electrode and the temperature electrode. When the electrodes are placed in a solution, a voltage (mV) is generated depending on the hydrogen activity of the solution. The varying voltage (potential) is dependent on the acidity or alkalinity of the solution and varies with the hydrogen ion activity in a known manner, the Nernst Equation. The potential (voltage) of the glass electrode is compared to the potential of the reference electrode and the difference between the two potentials is the measured potential. When placed in a pH 7 buffer most electrodes are designed to produce a zero (0) mV potential. As the solution becomes more acidic (lower pH) the potential of the glass electrode becomes more positive (+ mV) in comparison to the reference electrode and as the solution becomes more alkaline (higher pH) the potential of the glass electrode becomes more negative (- mV) in comparison to the reference electrode. The Nernst Equation shows the relationship between temperature and its affect on the activity of the hydrogen ion. At 25°C, each additional pH unit change represents a +/- 59.16 mV change in the potential of the glass electrode from a starting point of pH 7 (0 mV). -

Chapter 9 Ideal and Real Solutions

2/26/2016 CHAPTER 9 IDEAL AND REAL SOLUTIONS • Raoult’s law: ideal solution • Henry’s law: real solution • Activity: correlation with chemical potential and chemical equilibrium Ideal Solution • Raoult’s law: The partial pressure (Pi) of each component in a solution is directly proportional to the vapor pressure of the corresponding pure substance (Pi*) and that the proportionality constant is the mole fraction (xi) of the component in the liquid • Ideal solution • any liquid that obeys Raoult’s law • In a binary liquid, A-A, A-B, and B-B interactions are equally strong 1 2/26/2016 Chemical Potential of a Component in the Gas and Solution Phases • If the liquid and vapor phases of a solution are in equilibrium • For a pure liquid, Ideal Solution • ∆ ∑ Similar to ideal gas mixing • ∆ ∑ 2 2/26/2016 Example 9.2 • An ideal solution is made from 5 mole of benzene and 3.25 mole of toluene. (a) Calculate Gmixing and Smixing at 298 K and 1 bar. (b) Is mixing a spontaneous process? ∆ ∆ Ideal Solution Model for Binary Solutions • Both components obey Rault’s law • Mole fractions in the vapor phase (yi) Benzene + DCE 3 2/26/2016 Ideal Solution Mole fraction in the vapor phase Variation of Total Pressure with x and y 4 2/26/2016 Average Composition (z) • , , , , ,, • In the liquid phase, • In the vapor phase, za x b yb x c yc Phase Rule • In a binary solution, F = C – p + 2 = 4 – p, as C = 2 5 2/26/2016 Example 9.3 • An ideal solution of 5 mole of benzene and 3.25 mole of toluene is placed in a piston and cylinder assembly. -

Raoult's Law – Partition Law

BAE 820 Physical Principles of Environmental Systems Henry’s Law - Raoult's Law – Partition law Dr. Zifei Liu Biological and Agricultural Engineering Henry's law • At a constant temperature, the amount of a given gas that dissolves in a given type and volume of liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas in equilibrium with that liquid. Pi = KHCi • Where Pi is the partial pressure of the gaseous solute above the solution, C is the i William Henry concentration of the dissolved gas and KH (1774-1836) is Henry’s constant with the dimensions of pressure divided by concentration. KH is different for each solute-solvent pair. Biological and Agricultural Engineering 2 Henry's law For a gas mixture, Henry's law helps to predict the amount of each gas which will go into solution. When a gas is in contact with the surface of a liquid, the amount of the gas which will go into solution is proportional to the partial pressure of that gas. An equivalent way of stating the law is that the solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid. the solubility of gases generally decreases with increasing temperature. A simple rationale for Henry's law is that if the partial pressure of a gas is twice as high, then on the average twice as many molecules will hit the liquid surface in a given time interval, Biological and Agricultural Engineering 3 Air-water equilibrium Dissolution Pg or Cg Air (atm, Pa, mol/L, ppm, …) At equilibrium, Pg KH = Caq Water Caq (mol/L, mole ratio, ppm, …) Volatilization Biological and Agricultural Engineering 4 Various units of the Henry’s constant (gases in water at 25ºC) Form of K =P/C K =C /P K =P/x K =C /C equation H, pc aq H, cp aq H, px H, cc aq gas Units L∙atm/mol mol/(L∙atm) atm dimensionless -3 4 -2 O2 769 1.3×10 4.26×10 3.18×10 -4 4 -2 N2 1639 6.1×10 9.08×10 1.49×10 -2 3 CO2 29 3.4×10 1.63×10 0.832 Since all KH may be referred to as Henry's law constants, we must be quite careful to check the units, and note which version of the equation is being used. -

Effect of the Critical Solution Temperature of a Partial Miscible Phenol-Water Solution with Addition of Potassium Chloride

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 54(1), January - February 2019; Article No. 19, Pages: 109-112 ISSN 0976 – 044X Research Article Effect of the Critical Solution Temperature of a Partial Miscible Phenol-Water Solution with Addition of Potassium Chloride Chinmaya Keshari Sahoo*1, Hemanta Kumar Khatua2, Jimidi Bhaskar3, D. Venkata Ramana4 1Department of Pharmaceutics, Malla Reddy College of Pharmacy (Affiliated to Osmania University), Maisammaguda, Hyderabad, Telangana-500014, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, Princeton College of Pharmacy (Affiliated to JNTUH), Korremula, Hyderabad, Telangana-500088, India. 3Department of Pharmacy, Avanthi Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Gunthapally (V), Near Ramoji Film City, Hyderabad, Telangana-501505, India. 4Department of pharmaceutical Technology, Netaji Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Toopranpet, Yadadri Bhongir, Telangana-508252, India. *Corresponding author’s E-mail: [email protected] Received: 05-12-2018; Revised: 25-12-2018; Accepted: 08-01-2019. ABSTRACT Partially miscible liquids become more soluble with the increase in temperature and at a certain temperature they are completely miscible. This temperature is known as the critical solution temperature (CST) or consolute temperature. The temperature above the phase gets affected by the addition of impurities. To observe the miscibility temperature, the mixture was heated in a boiling tube until the turbidity disappeared and the final temperature was noted. Then, the mixture was cooled down and the temperature noted when the turbidity reappeared. Solutions of impurities of different concentrations were formed and their effect on the phase was analyzed. It was found that addition of ionic compound KCl, in phenol- water system show lesser increase in CST as they decrease the miscibility to a lesser extent. -

A Solution Is a Type of Mixture

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § KEY CONCEPT A solution is a type of mixture. BEFORE, you learned NOW, you will learn • Ionic or covalent bonds hold a • How a solution differs from compound together other types of mixtures • Chemical reactions produce • About the parts of a solution chemical changes • How properties of solutions • Chemical reactions alter the differ from properties of their arrangements of atoms separate components VOCABULARY EXPLORE Mixtures solution p. 111 Which substances dissolve in water? solute p. 112 solvent p. 112 PROCEDURE MATERIALS suspension p. 113 • tap water 1 Pour equal amounts of water into each cup. • 2 clear plastic cups 2 Pour one spoonful of table salt into one • plastic spoon of the cups. Stir. • table salt • flour 3 Pour one spoonful of flour into the other cup. Stir. 4 Record your observations. WHAT DO YOU THINK? • Did the salt dissolve? Did the flour dissolve? • How can you tell? The parts of a solution are mixed evenly. VOCABULARY A mixture is a combination of substances, such as a fruit salad. Remember to use the The ingredients of any mixture can be physically separated from each strategy of your choice. You might use a four square other because they are not chemically changed—they are still the same diagram for solution . substances. Sometimes, however, a mixture is so completely blended that its ingredients cannot be identified as different substances. A solution is a type of mixture, called a homogeneous mixture, that is the same throughout. A solution can be physically separated, but all portions of a solution have the same properties. If you stir sand into a glass of water, you can identify the sand as a separate substance that falls to the bottom of the glass. -

Lecture Ch. 9: Solution Concentration Units

Lecture Ch. 9: Solution Concentration Units When working with solutions, it is convenient to use units that express concentration – that is to say, how much solute there is per a set amount of solution or solvent. Highly concentrated solutions have a lot of solute dissolved. Weakly concentrated solutions have very little solute dissolved. Some solutions will have as little as one part solute/ 10,000,000,000 parts solvent ! For some mixtures, particularly liquids dissolved in liquids, dissolving in any proportion will lead to a solution – we call these solutions miscible in all proportions. For others, only a maximum amount of solute can be dissolved in solution before the rest will start to precipitate out. At that point the solution is saturated . For solutions in liquid solvents, there are a number of units we can use to express concentration. Some are better for extremely dilute concentrations, and some are better used for relatively concentrated solutions. Some will be used by chemists, some by biologists, and some by laboratory technicians. As professionals in the health field, you should be comfortable working with all of the concentration units we’ll cover in this chapter. I. Molarity Molarity is most often used by chemists in the practical lab. You may already have encountered it during your own lab classes here . Molarity stands for Moles of Solute / Liters of Solution. The most common mistake I see students make is to think that Molarity, or its shorthand symbol, M, stands for moles. This is not true. It is moles PER liter of solution. The shorthand for moles is mol, there is no single letter shorthand for moles.