From Gaza to Lebanon and Back Gabriel Siboni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reps. Knollenberg, David Law, Moss, Bieda, Casperson, Clack, Condino

Reps. Knollenberg, David Law, Moss, Bieda, Casperson, Clack, Condino, Dean, DeRoche, Garfield, Hildenbrand, Horn, Rick Jones, LaJoy, Palmer, Pastor, Proos, Scott, Stahl and Wojno offered the following resolution: House Resolution No. 159. A resolution to urge the President of the United States, the United States Congress and the United States Department of State to consult with appropriate officials in Syria, Lebanon, and the Palestinian Authority regarding the status of missing Israeli soldiers and demand the immediate and unconditional release of three Israeli soldiers currently believed to be held by Hamas and Hezbollah. Whereas, The United States Congress expressed its concern for Israeli soldiers missing in Lebanon and the Hezbollah-controlled territory of Lebanon in Public Law 106-89 (113 Stat. 1305; November 8, 1999) which required the Secretary of State to probe into the disappearance of Israeli soldiers with appropriate government officials of Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian Authority, and other governments in the region, and to submit to the Congress reports on those efforts and any subsequent discovery of relevant information; and Whereas, Israel completed its withdrawal from southern Lebanon on May 24, 2000. On June 18, 2000, the United Nations Security Council welcomed and endorsed United Nations Secretary- General Kofi Annan's report that Israel had withdrawn completely from Lebanon under the terms of United Nations Security Council Resolution 425 (1978). Nearly five years later, Israel completed its withdrawal from Gaza on September 12, 2005; and Whereas, On June 25, 2006, Hamas and allied terrorists crossed into Israel to attack a military post, killing two soldiers and wounding a third, Gilad Shalit, who was kidnapped. -

Congressional Record—House H7762

H7762 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE July 12, 2007 we will proceed with next week’s work and Defense; Commander, Multi-Na- ried Karnit when he was captured, and next week. tional Forces—Iraq; the United States his wife had to spend their 1-year anni- f Ambassador to Iraq; and the Com- versary alone, wondering where her mander of United States Central Com- husband was and what condition he was HOUR OF MEETING ON TOMORROW mand. in. His family and friends wrote: AND ADJOURNMENT FROM FRI- GEORGE W. BUSH. ‘‘He’s a loving, caring person, always DAY, JULY 13, 2007 TO MONDAY, THE WHITE HOUSE, July 12, 2007. ready to offer a helping hand in any JULY 16, 2007 f situation. He is a man of principles and Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, I ask values, knowledgeable in many varied unanimous consent that when the SPECIAL ORDERS subjects.’’ House adjourns today, it adjourn to The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under Unfortunately, Eldad and Udi are not meet at 4 p.m. tomorrow, and further, the Speaker’s announced policy of Jan- alone among Israel’s missing soldiers. when the House adjourns on that day, uary 18, 2007, and under a previous Three weeks before their capture, it adjourn to meet at 12:30 p.m. on order of the House, the following Mem- Hamas kidnapped IDF soldier Gilad Monday, July 16, 2007, for morning- bers will be recognized for 5 minutes Shalit. The Shalit family has also met hour debate. each. with many communities across the The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. f United States, urging people to remem- ELLISON). -

Analysis: 'Disproportion Has Always Been the Name of the Game' | Jerusalem Post Page 1 of 2

Analysis: 'Disproportion has always been the name of the game' | Jerusalem Post Page 1 of 2 Want To Quit Your Job? The Jerusalem Post Mobile Graphic Designer Support Israel Earn 3K-5K Per Week-From Home Breaking news from Israel Stay up Adobe Photoshop CS Quark XPress Help Yad Ezra VeShulamit. Feeding Let Me Show You How to date Kамтес 1-800-22-22-28 Israel's Hungry Children & Families www.1kdailyjob.com mobile.jpost.com www.kamtec.com www.yad-ezra.org Analysis: 'Disproportion has always been the name of the game' Jun. 18, 2008 abe selig , THE JERUSALEM POST Trading Lebanese terrorist Samir Kuntar for captured IDF reservists Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev is important even if the two soldiers are no longer alive, Yoram Schweitzer of the Institute for National Security Studies said on Wednesday, as the deal was apparently moving through its final stages. "Disproportion has always been the name of the game," Schweitzer said, alluding to the possibility that the government wasn't negotiating with Hizbullah for the soldiers themselves, but for their remains. He is a senior research fellow and director of the Program on Terrorism and Low Intensity Conflict at the institute. But the prospect of such a deal raises questions as to how the Israeli public will respond if the two IDF soldiers are dead, adding a heartrending tone to this final chapter of the Second Lebanon War, which was waged to bring them home in the first place. "Even if they are dead, which I hope they're not," Schweitzer continued, "we will give two families knowledge of the fate of their loved ones, and I wouldn't underestimate that fact. -

Congressional Record—House H2447

March 13, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2447 every turn, we will never retreat, and we will I ask my colleagues to join me in supporting House Resolution 107, calling for the imme- prevail because the cause of freedom is just Israel and condemning these heinous acts, diate and unconditional release of the Israeli and righteous. As one of my heroes, President and cast a vote in favor of H. Res. 107. soldiers held captive by Hamas and Hezbollah John F. Kennedy, once said, ‘‘Let every nation Mr. GARRETT of New Jersey. Mr. Speaker, since last summer. know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we it’s been more than seven months now and The critical bipartisan legislation being intro- shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet many have forgotten about the three Israeli duced today calls for the immediate and un- any hardship, support any friend, oppose any soldiers kidnapped by Hamas and Hezbollah: conditional release of the three Israeli soldiers foe, in order to assure the survival and the Ehud Goldwasser, Eldad Regev, and Gilad who were captured last summer. Ehud success of liberty.’’ Today we renew this Shalit. Hezbollah seems to have forgotten that Goldwasser, 31, and Eldad Regev, 26, were pledge. last year’s hostilities ended only after there kidnapped by Hezbollah on July 12, 2006. This resolution also makes it clear that while were promises regarding the return of the Gilad Shalit was kidnapped by Hamas on we do not shrink from the fight against ter- Israeli men. This just goes to reinforce the fact June 25, 2006. -

Please Scroll Down for Article

This article was downloaded by: [Schleifer, Ron] On: 25 March 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 909860250] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Terrorism and Political Violence Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713636843 Psyoping Hezbollah: The Israeli Psychological Warfare Campaign During the 2006 Lebanon War Ron Schleifer a a Ariel University Center, Samaria Online Publication Date: 01 April 2009 To cite this Article Schleifer, Ron(2009)'Psyoping Hezbollah: The Israeli Psychological Warfare Campaign During the 2006 Lebanon War',Terrorism and Political Violence,21:2,221 — 238 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09546550802544847 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09546550802544847 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

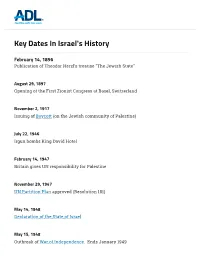

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution -

Hezbollah: a Localized Islamic Resistance Or Lebanon's Premier

Hezbollah: A localized Islamic resistance or Lebanon’s premier national movement? Andrew Dalack Class of 2010 Department of Near East Studies University of Michigan Introduction Lebanon’s 2009 parliamentary elections was a watershed moment in Lebanon’s history. After having suffered years of civil war, political unrest, and foreign occupation, Lebanon closed out the first decade of the 21st century having proved to itself and the rest of the world that it was capable of hosting fair and democratic elections. Although Lebanon’s political structure is inherently undemocratic because of its confessionalist nature, the fact that the March 8th and March 14th coalitions could civilly compete with each other following a brief but violent conflict in May of 2008 bore testament to Lebanon’s growth as a religiously pluralistic society. Since the end of Lebanon’s civil war, there have been few political movements in the Arab world, let alone Lebanon, that have matured and achieved as much as Hezbollah has since its foundation in 1985. The following thesis is a dissection of Hezbollah’s development from a localized militant organization in South Lebanon to a national political movement that not only represents the interests of many Lebanese, but also functions as the primary resistance to Israeli and American imperialism in Lebanon and throughout the broader Middle East. Particular attention is paid to the shifts in Hezbollah’s ideology, the consolidation of power and political clout through social services, and the language that Hezbollah uses to define itself. The sources I used are primarily secondhand; Joseph Alagha’s dissertation titled, The Shifts in Hizbullah’s Ideology: Religious Ideology, Political Ideology, and Political Program was one of the more significant references I used in substantiating my argument. -

Who's Who of the Prisoner Swap

Whoʼs who of the prisoner swap 7/9/18, 2)44 PM Who’s who of the prisoner swap At 9 a.m. Wednesday, five Lebanese prisoners – Samir Kantar, a Lebanese Palestinian Liberation Front Member who has been detained for murder in Israel since 1979; and Khodor Zidan, Maher Kurani, Mohammed Sarur and Hussein Suleiman, Hezbollah fighters captured during the 2006 war – will cross the Israeli border and enter Lebanon as part of an Israel-Hezbollah prisoner swap deal that has been in the works for months. The swap will close Lebanon’s detainee file with Israel, making Lebanon the first Arab country not at peace with the Jewish State to do so. In exchange for the live prisoners and the remains of 200 Hezbollah fighters and Palestinians, Hezbollah will be handing over Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev, Israeli servicemen who were taken hostage by party militants in July 2006, prompting the 34-day war. Both are presumed dead. https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/commentary/whos_who_of_the_prisoner_swap Page 1 of 6 Whoʼs who of the prisoner swap 7/9/18, 2)44 PM This will be the eighth prisoner swap to take place between Israel and Hezbollah since 1991, with the most recent deal taking place in late 2007. Negotiations over potential deals have been ongoing since late 2006, under the auspices of the UN. The move has been met with some controversy, however. Aside from the release of Kantar, who is vilified in Israel for the brutal nature of his crime, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert has said that Hezbollah has not kept its end of the deal. -

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in Partial Fulfil

THE DAHIYEH DOCTRINE: THE CONDITIONS UNDER WHICH STATES CAN ESTABLISH ASYMMETRIC DETERRENCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Rafael D. Frankel, M.S. Washington, DC July 3, 2013 Copyright 2013 by Rafael D. Frankel All Rights Reserved ii THE DAHIYEH DOCTRINE: THE CONDITIONS UNDER WHICH STATES CAN ESTABLISH ASYMMETRIC DETERRENCE Rafael D. Frankel, M.S. Thesis Advisor: Daniel L. Byman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT For the last decade, a growing body of research has sough to understand how classical deterrence methods could be adapted by states to establish asymmetric deterrence against non-state militant groups. Various strategies were suggested, but the research undertaken to date focused nearly exclusively on the actions of the defending state. This research project is the first formal effort to discover under what conditions deterrence against such groups can be established by focusing on important attributes of the non-state groups themselves. The result is the development of the Asymmetric Deterrence Matrix (ADM), which in eight temporally-bound case studies involving Hamas and Hezbollah successfully predicts the level of deterrence Israel should have been able to achieve against those groups at given periods of time. This research demonstrates that there are four main causal factors related to a non-state group’s characteristics that constrain and encourage the success of asymmetric deterrence strategies by states: elements of statehood (territorial control, political authority, and responsibility for a dependent population), organizational structure, ideology, and inter- factional rivalries. -

High Price 7/9/18, 1�39 PM High Price

High price 7/9/18, 1(39 PM High price Israeli officials stated on Monday that a prisoner swap with Hezbollah will take place in roughly two weeks. The swap will guarantee the release of five Lebanese detainees – Samir Kantar purportedly being one of them – and the remains of Hezbollah militiamen as well as Palestinian prisoners in return for two Israeli POWs. Negotiations over the deal have been going on since late 2006 under the auspices of the United Nations, and more recently under German mediation. This Sunday, June 29, Israel’s cabinet voted in favor of the deal. The move has been met with criticism in Israel over the fate of the two soldiers, Eldad Regev and Ehud Goldwasser, and the release Kantar, who is currently serving a 542-year murder sentence. But according to Dr. Imad Salamey, assistant professor of politics and international affairs at LAU, the https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/commentary/high_price Page 1 of 4 High price 7/9/18, 1(39 PM swap comes at a critical time for both sides and can be interpreted as a victory for outgoing Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. The swap is also deflecting attention from “Olmert’s various internal scandals, and reassures the Israeli public that the government is still well,” he said. In addition, the move emphasizes that “Hezbollah no longer has a pretext to attack Israeli soldiers” and will also help Israel put pressure on the Lebanese government to negotiate, as “the major aspects of conflict [between the states] have been reduced.” On the Hezbollah front, the swap will allow for the party to improve its image after it used its weapons domestically in May, as it reinforces its “image as a resistance movement [that achieved] its aims in the July 2006 operation.” The technicalities The Israeli daily Haaretz reported that the swap would take place on July 12, in parallel with Hezbollah celebrations marking the second anniversary of the July War. -

1 Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 19/17 Aktuelles Aus Israelischen

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 19/17 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 1.-15. November Die Themen dieser Ausgabe 1. Leichen für Leichen .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. 22 Jahre nach Mord an Yitzhak Rabin ............................................................................................................. 3 3. Israel und Saudi-Arabien nähern sich einander an .......................................................................................... 5 4. Medienquerschnitt ............................................................................................................................................ 6 1. Leichen für Leichen fighters captured in 2006, plus the bodies of 199 Pal- Vertreter von Israels Regierung und Sicherheitsappa- estinian, Lebanese of Arab fighters, in exchange for rat warnten den Islamischen Jihad vor einem Vergel- the bodies of IDF reservists Ehud Goldwasser and tungsschlag. Die palästinensischen Extremisten hat- Eldad Regev. Kuntar, who was considered a hero for ten zuvor mit Rache für die Zerstörung eines gehei- bludgeoning to death a four-year-old girl in a Naha- men Grenztunnels gedroht, bei der zwölf ihrer Män- riya attack, was later killed in an IDF air strike in Syria ner den Tod fanden. Fünf der Toten konnten von Is- in 2015. “We intend to return our sons home. There rael geborgen werden. Die Hoffnung ist, die Leichen are no free gifts,” Netanyahu declared in a brief state- gegen die -

Understanding Political Influence in Modern-Era Conflict: a Qualitative Historical Analysis of Hassan Nasrallah's Speeches

Understanding Political Influence in Modern-Era Conflict: A Qualitative Historical Analysis of Hassan Nasrallah’s Speeches by Reem A. Abu-Lughod and Samuel Warkentin Abstract This research examines and closely analyzes speeches delivered by Hezbollah’s secretary general and spokesman, Hassan Nasrallah. We reveal that several significant political phenomena that have occurred in Lebanon were impacted by the intensity of speeches delivered by Nasrallah; these three events being the 2006 War, the Doha Agreement, and the 2008 prisoner exchange. Nasrallah’s speeches with significant key words and themes, that are reflective of the three selected events, have been collected from various transcribed news media sources and analyzed using a qualitative historical approach. Finally, the research study uses latent analysis to assess Nasrallah’s underlying implications of his speeches by identifying key words and themes that he uses to influence his audience Introduction he present globalization of extremist discourse and its impact on international relations as a whole have historical precedents.[1] Whether it’s print media, television, the “T internet, or any other form of communication, charismatic leaders of influential organizations have led their audience to believe in certain ideologies that are deemed hopeful and powerful, all through their emotional and authoritative speeches. One such leader is Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s secretary general. Nasrallah has been an influential leader of Hezbollah, inspiring his supporters and engaging them at an emotional level to garner more support of his actions. Through his rhetoric, he has been able to relate to his audience, in particular the majority of the Shi’a community in Lebanon and those who are in opposition to the Israeli occupation of Palestine; all with a strategic strength to gain their commitment of his broad and open pleas.