US-Psuedoclassificationssi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Name Is Robert Maclean. Currently My Whistleblower Protection Act Case Is the First Involving the Act That Will Be Heard by the Supreme Court

TESTIMONY OF ROBERT MACLEAN before the HOUSE OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM COMMITTEE, SUBCOMMITTEE ON FEDERAL WORKFORCE, U.S. POSTAL SERVICE AND THE CENSUS September 9, 2014 Mr. Chairman: Thank you for inviting my testimony. My name is Robert MacLean. Currently my Whistleblower Protection Act case is the first involving the Act that will be heard by the Supreme Court. But I am not here to talk about the legal arguments. I want to share why I had to blow the whistle, and what it means for our country to protect the freedom to warn. The timeline below shares a whistleblowing experience I never wanted to have. But it forced me to make the most difficult choices and decisions of my life, about my duty to the country as a public servant and law enforcement officer. The timeline below chronicles a series of events that has changed my life forever, and may have been even more significant for our nation’s safety. 1992 — After four years as a nuclear weapons specialist, I was honorably discharged from the Air Force with a Top Secret clearance and the option to reenlist. 1996 — I became a Border Patrol Agent in the San Diego Sector. Not to be confused with a port inspector you see working at land border entry points or airports. I patrolled the vast area between entry points. 32 days after the 9/11 attacks — I was specially recruited to be in the first class of U.S. Federal Air Marshals (Air Marshals) to graduate after the 9/11 attacks. July 26, 2003 — Four months after the invasion of Iraq, all Air Marshals throughout the country were recalled for mandatory unprecedented in-office emergency suicidal Al-Qaeda hijacking training. -

Brief in Opposition ______

No. 13-894 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________ DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, Petitioner, v. ROBERT J. MACLEAN, Respondent. _________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit _________ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION _________ THOMAS DEVINE NEAL KUMAR KATYAL GOVERNMENT Counsel of Record ACCOUNTABILITY PROJECT AMANDA K. RICE 1612 K Street, N.W. HOGAN LOVELLS US LLP Suite 1100 555 Thirteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 637-5600 [email protected] Counsel for Respondent i QUESTION PRESENTED In recognition of the crucial role federal employees play in uncovering unlawful, wasteful, and danger- ous government activity, Congress has enacted strong protections for government whistleblowers. One such provision provides that agencies may not retaliate against employees who disclose information revealing, among other things, “any violation of any law, rule, or regulation” or “a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety.” 5 U.S.C. § 2302(b)(8)(A). There is an exception, however, for “disclosure[s] * * * specifically prohibited by law” or by certain Executive orders. Id. Disclosure of certain kinds of sensitive but unclas- sified information, referred to as “Sensitive Security Information,” is prohibited by regulation. See 49 C.F.R. Pt. 1520. Those regulations are promulgated pursuant to a general statutory delegation of author- ity. See 49 U.S.C.A. § 114(r)(1). The question presented is whether a disclosure of Sensitive Security Information is “specifically prohib- ited by law” within the meaning of Section 2302(b)(8)(A). -

North Atlantic Regional Business Law Association

Published by Husson University Bangor, Maine For the NORTH ATLANTIC REGIONAL BUSINESS LAW ASSOCIATION EDITORS IN CHIEF William B. Read Husson University Marie E. Hansen Husson University BOARD OF EDITORS Robert C. Bird Gerald A. Madek University of Connecticut Bentley University Gerald R. Ferrera Carter H. Manny Bentley University University of Southern Maine Stephanie M. Greene Christine N. O’Brien Boston College Boston College William E. Greenspan Lucille M. Ponte University of Bridgeport Florida Coastal School of Law Anne-Marie G. Hakstian Margo E.K. Reder Salem State College Boston College Chet Hickox Patricia Q. Robertson University of Rhode Island Arkansas State University Stephen D. Lichtenstein David Silverstein Bentley University Suffolk University David P. Twomey Boston College i GUIDELINES FOR 2011 Papers presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting and Conference will be considered for publication in the Business Law Review. In order to permit blind refereeing of manuscripts, papers must not identify the author or the author’s institutional affiliation. A removable cover page should contain the title, the author’s name, affiliation, and address. If you are presenting a paper and would like to have it considered for publication, you must submit two clean copies, no later than March 29, 2011 to: Professor William B. Read Husson University 1 College Circle Bangor, Maine 04401 The Board of Editors of the Business Law Review will judge each paper on its scholarly contribution, research quality, topic interest (related to business law or the legal environment of business) writing quality, and readiness for publication. Please note that, although you are welcome to present papers relating to teaching business law, those papers will not be eligible for publication in the Business Law Review. -

Prohibited Personnel Practices (PPP) Complaint to the OSC, November 17, 2006 3) OSC Letter to Robert Maclean Closing His PPP Complaint, December 7, 2006

Project On Government Oversight Breaking the Sound Barrier: Experiences of Air Marshals Confirm Need for Reform at the OSC November 25, 2008 666 11th Street, NW, Suite 900 • Washington, DC 20001-4542 • (202) 347-1122 Fax: (202) 347-1116 • E-mail: [email protected] • www.pogo.org POGO is a 501(c)3 organization CONTENTS Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................4 Introduction......................................................................................................................................7 The Office of Special Counsel: Mission Unaccomplished..............................................................9 Whistleblower Retaliation at the Federal Air Marshal Service.....................................................14 Air Marshals, Like Other Whistleblowers, Travel Alone..............................................................18 Looking for Excuses Not to Help..................................................................................................21 The OSC Does Not Act to Stop the Retaliation.............................................................................23 The OSC Not Using Its Disclosure Process to Push for the Truth................................................24 OSC Program to Inform Employees of Whistleblower Rights Lags Behind................................28 Conclusion.....................................................................................................................................30 -

Section 4: Business Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Supreme Court Preview Conferences, Events, and Lectures 2014 Section 4: Business Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School, "Section 4: Business" (2014). Supreme Court Preview. 244. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview/244 Copyright c 2014 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview IV. Business In This Section: New Case: 13-433 Integrity Staffing Solutions, Inc. v. Busk p. 256 Synopsis and Questions Presented p. 256 “AMAZON WAREHOUSE WORKER PAY SUIT HEADS TO SUPREME COURT” p. 262 Claire Zillman “SUPREME COURT MAY FINALLY CLARIFY COMPENSABLE TIME” p. 264 Kenneth W. Gage “AMAZON WORKERS WANT PAY FOR TIME SPENT AT SECURITY p. 268 CHECKPOINT” Aaron Kase “FLSA ACTION CAN COEXIST WITH STATE CLASS CLAIMS: 9TH CIRC.” p. 270 Ben James New Case: 13-894 Department of Homeland Security v. MacLean p. 272 p. Synopsis and Questions Presented p. 272 “SUPREME COURT TO DECIDE WHETHER AIR MARSHAL SHOULD BE p. 280 PROTECTED AS WHISTLEBLOWER” Robert Barnes “IS HIKE IN WHISTLEBLOWER CLAIMS A SIGN OF PROGRESS OR GROWING p. 282 MISTRUST?” Jack Moore “FED. CIRC. UPS PROTECTION FOR WHISTLEBLOWERS’ DISCLOSURES” p. 285 Bill Donahue New Case: 13-485 Comptroller v. Wynne p. 287 Synopsis and Questions Presented p. 287 “SUPREME COURT AGREES TO HEAR LANDMARK CASE ON WHETHER p. 303 STATES MAY TAX INCOME EARNED IN OTHER STATES” Kelly Phillips Erb “SUPREME COURT TO HEAR MARYLAND DOUBLE TAXATION CASE” p. -

RESPONDENT's BRIEF (P) Case: 11-3231 Document: 33 Page: 2 Filed:WEST/CRS 05/30/2012

Case: 11-3231 Document: 33 Page: 1 Filed: 05/30/2012 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIJIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIllIIIII111111 USFC2011-3231-03 {DCOFAD02-A3F3-41 77-B1 7B-D68EA05E647F} {118231}{54-120612:113016}{053012} RESPONDENT'S BRIEF (P) Case: 11-3231 Document: 33 Page: 2 Filed:WEST/CRS 05/30/2012 2011-3231 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT ROBERT J. MACLEAN, Petitioner, We DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, Respondent. i i Petition for Review of the Merit Systems Protection Board decision in Case No. SF-0752-06-0611-I-2. i , BRIEF AND SUPPLEMENTAL APPENDIX FOR RESPONDENT, DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY STUART F. DELERY Acting Assistant Attorney General JEANNE E. DAVIDSON fllfP_. -i_roi_ Director U_eOu_ o_ ter-_ TODD M. HUGHES 30 701l Deputy Director MICHAEL P. GOODMAN Trial Attorney U.S. Department of Justice Civil Division PO Box 480; Ben Franklin Station Washington, DC 20044 Tel: (202) 305-2087 May 30, 2012 Attorneys for Respondent Case: 11-3231 Document: 33 Page: 3 Filed: 05/30/2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................... ........................................................... iii STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES ................................................................... vi STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES ............................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................................................. -

Federal Whistleblower Protections May Face Greatest Test Yet Law360

1/26/2017 Federal Whistleblower Protections May Face Greatest Test Yet Law360 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Federal Whistleblower Protections May Face Greatest Test Yet By Debra Katz and Aaron Blacksberg, Katz Marshall & Banks LLP Law360, New York (January 25, 2017, 5:41 PM EST) In its first days, the Trump administration has ordered media and social media blackouts at several federal agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of the Interior, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. While these orders may turn out to be normal pains of transition we fear that may not be the case given the antipathy President Donald Trump and other administration officials have expressed toward climate change advocates and scientists. This may be the first salvo in a campaign to gag government employees, particularly scientists, and deter or outright prevent them from speaking out on matters of public importance. Debra S. Katz This moment provides an important opportunity for federal employees, along with members of the legal profession, media and general public, to become better acquainted with federal employee whistleblower protections. As discussed below, federal employees are legally protected from retaliation, under certain circumstances, for speaking to members of the media. And federal agencies who attempt to gag employees may violate the law in doing so. Overview of Federal Employee Whistleblower Protections Law Aaron D. -

Oversight of the Transportation Security Administration: First Hand and Government Watchdog Accounts of Agency Challenges

S. Hrg. 114–439 OVERSIGHT OF THE TRANSPORTATION SECURITY ADMINISTRATION: FIRST HAND AND GOVERNMENT WATCHDOG ACCOUNTS OF AGENCY CHALLENGES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 9, 2015 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 97–353 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin Chairman JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware ROB PORTMAN, Ohio CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri RAND PAUL, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey JONI ERNST, Iowa GARY C. PETERS, Michigan BEN SASSE, Nebraska KEITH B. ASHDOWN, Staff Director MICHAEL LUEPTOW, Investigative Counsel GABRIELLE A. BATKIN. Minority Staff Director JOHN P. KILVINGTON, Minority Deputy Staff Director BRIAN TURBYFILL, Minority Senior Professional Staff Member LAURA W. KILBRIDE, Chief Clerk LAUREN M. CORCORAN, Hearing Clerk (II) C O N T E N T S Opening statements: Page Senator Johnson .............................................................................................. -

A Review of the Whistle- Blower Protection Enhancement Act

FIVE YEARS LATER: A REVIEW OF THE WHISTLE- BLOWER PROTECTION ENHANCEMENT ACT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION FEBRUARY 1, 2017 Serial No. 115–10 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–314 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:36 Aug 09, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\26314.TXT APRIL KING-6430 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM Jason Chaffetz, Utah, Chairman John J. Duncan, Jr., Tennessee Elijah E. Cummings, Maryland, Ranking Darrell E. Issa, California Minority Member Jim Jordan, Ohio Carolyn B. Maloney, New York Mark Sanford, South Carolina Eleanor Holmes Norton, District of Columbia Justin Amash, Michigan Wm. Lacy Clay, Missouri Paul A. Gosar, Arizona Stephen F. Lynch, Massachusetts Scott DesJarlais, Tennessee Jim Cooper, Tennessee Trey Gowdy, South Carolina Gerald E. Connolly, Virginia Blake Farenthold, Texas Robin L. Kelly, Illinois Virginia Foxx, North Carolina Brenda L. Lawrence, Michigan Thomas Massie, Kentucky Bonnie Watson Coleman, New Jersey Mark Meadows, North Carolina Stacey E. Plaskett, Virgin Islands Ron DeSantis, Florida Val Butler Demings, Florida Dennis A. Ross, Florida Raja Krishnamoorthi, Illinois Mark Walker, North Carolina Jamie Raskin, Maryland Rod Blum, Iowa Vacancy Jody B. -

Responding to the September 11 Terrorist Attacks

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Center for Cultural Resources National Park Service Responding to the September 11 Terrorist Attacks Janet A. McDonnell 1 2 3 4 The National Park Service: Responding to the September 11 Terrorist Attacks Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McDonnell, Janet A., 1952- The National Park Service : responding to the September 11 terrorist attacks / by Janet A. McDonnell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. United States. National Park Service. 2. September 11 Terrorist Attacks, 2001. I. Title. SB482.A4M338 2004 973.931--dc22 2004026454 Cover: U. S. Park Police patrol New York Harbor after the attacks. Inside cover, Maj. Tom Wilkins, U.S. Park Police, holds the American flag during rescue operations at Ground Zero. The National Park Service: Responding to the September 11 Terrorist Attacks Janet A. McDonnell National Park Service Department of the Interior iii Table of Contents Preface ...................................................................................................... vii Introduction ............................................................................................. x I. National Park Service’s Initial Response ........................................... 1 Main Interior Building, Tuesday, September 11, 2001 ............ 1 Continuity of Operations ......................................................... 4 Park Closures ............................................................................ 8 Support to the Department -

Aviation Security

AVIATION SECURITY: ARE WE TRULY PROTECTED? PART I AND A FRONTLINE PERSPECTIVE ON THE NEED FOR ENHANCED HUMAN RESOURCES AND EQUIPMENT, PART II HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION SECURITY AND INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 16, 2007 AND NOVEMBER 1, 2007 Serial No. 110–77 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 48–972 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 07:10 Sep 04, 2009 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\DOCS\110-HRGS\110-77\48972.TXT HSEC PsN: DIANE Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi, Chairman LORETTA SANCHEZ, California, PETER T. KING, New York EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts LAMAR SMITH, Texas NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MIKE ROGERS, Alabama Columbia BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana ZOE LOFGREN, California DAVID G. REICHERT, Washington SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin CHARLES W. DENT, Pennsylvania Islands GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina MARSHA BLACKBURN, Tennessee JAMES R. -

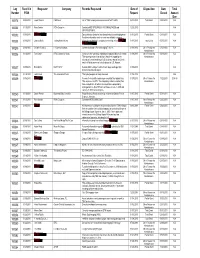

(B) (6) Documentation of Why He Was Denied Reinstatement/Employment

Log Recv'd in Requester Company Records Requested Date of Disposition Date Total Number FOIA Request Closed Amount Due 100175 02/02/2010 Laura Strickler CBS News List of TSES employees bonus amounts for FY 2009 02/01/2010 Total Grant 03/03/2010 N/A 100203 01/15/2010 Rose Santos FOIA Group Inc. Contracts #GS10F06LPA005, #GS10F06LPA0006 and 12/29/2010 N/A GS10F06LPA0010. 100232 01/13/2010 (b) (6) Documentation of why he was denied reinstatement/employment. 01/13/2010 Partial Grant 03/03/2010 N/A Proof that information sent via email was officially reviewed. 100233 01/13/2010 Zachary Roth Talking Points Memo Information pertaining to a subpoena involving writers (b) (6) 01/13/2010 Total Denial 06/30/2010 N/A (b) (6) 100235 01/14/2010 Christine Lindsey L3 Communications Contract awarded to Reveal Imaging Tech, Inc. 01/13/2010 Other Reason for 02/02/2010 N/A Nondisclosure 100236 01/14/2010 Tom Vacar KTVU Channel 2 News Answers to the questions regarding alleged prohibitions for certain 01/08/2010 Other Reason for 06/03/2010 N/A TSA spokespersons from talking to the press regarding the Nondisclosure attempted terrorist bombing of a Delta airliner bound for Detroit and/or full body scanners to be deployed at U.S. Airports. 100237 01/15/2010 Brian Mylar KSAT-12 TV Results 2009 testing of certified bomb dogs working at San 01/14/2010 N/A Antonio International Airport. 100238 01/15/2010 Josh Freed The Associated Press TSA’s pilot program for body scanners 01/14/2010 N/A 100239 01/15/2010 (b) (6) Record of every written passenger complaint filed against any 01/07/2010 Other Reason for 11/22/2010 $218 80 TSA employee at HPN.