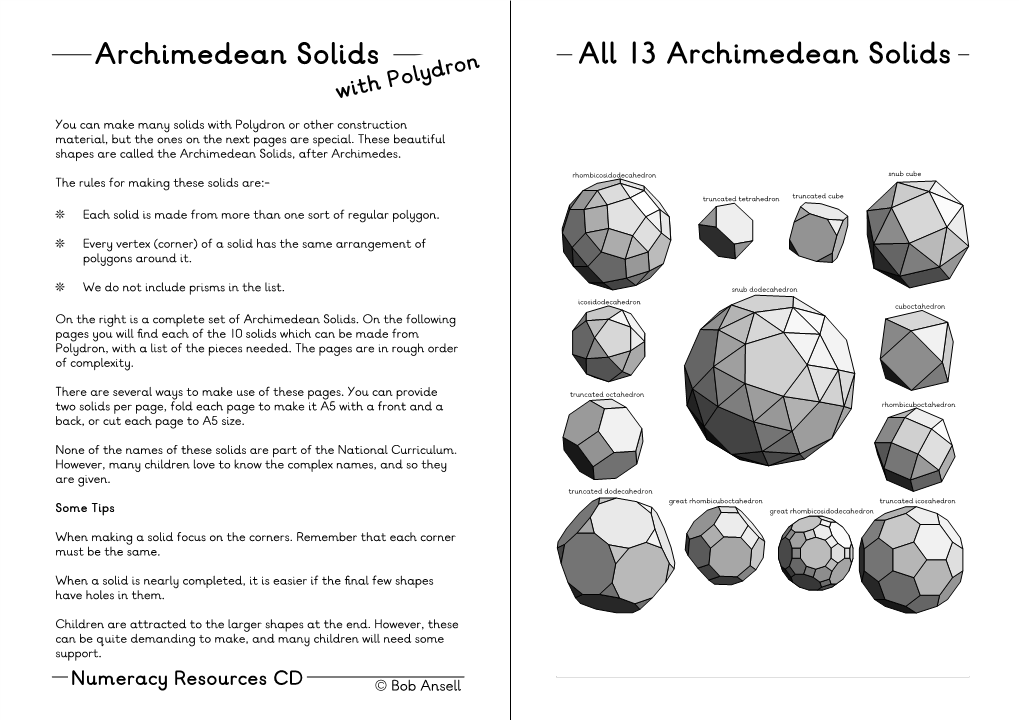

Archimedean Solids Ron All 13 Archimedean Solids Polyd With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Archimedean Or Semiregular Polyhedra

ON THE ARCHIMEDEAN OR SEMIREGULAR POLYHEDRA Mark B. Villarino Depto. de Matem´atica, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San Jos´e, Costa Rica May 11, 2005 Abstract We prove that there are thirteen Archimedean/semiregular polyhedra by using Euler’s polyhedral formula. Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 RegularPolyhedra .............................. 2 1.2 Archimedean/semiregular polyhedra . ..... 2 2 Proof techniques 3 2.1 Euclid’s proof for regular polyhedra . ..... 3 2.2 Euler’s polyhedral formula for regular polyhedra . ......... 4 2.3 ProofsofArchimedes’theorem. .. 4 3 Three lemmas 5 3.1 Lemma1.................................... 5 3.2 Lemma2.................................... 6 3.3 Lemma3.................................... 7 4 Topological Proof of Archimedes’ theorem 8 arXiv:math/0505488v1 [math.GT] 24 May 2005 4.1 Case1: fivefacesmeetatavertex: r=5. .. 8 4.1.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 8 4.1.2 All faces have at least four sides: p1 > 4 .............. 9 4.2 Case2: fourfacesmeetatavertex: r=4 . .. 10 4.2.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 10 4.2.2 All faces have at least four sides: p1 > 4 .............. 11 4.3 Case3: threefacesmeetatavertes: r=3 . ... 11 4.3.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 11 4.3.2 All faces have at least four sides and one exactly four sides: p1 =4 6 p2 6 p3. 12 4.3.3 All faces have at least five sides and one exactly five sides: p1 =5 6 p2 6 p3 13 1 5 Summary of our results 13 6 Final remarks 14 1 Introduction 1.1 Regular Polyhedra A polyhedron may be intuitively conceived as a “solid figure” bounded by plane faces and straight line edges so arranged that every edge joins exactly two (no more, no less) vertices and is a common side of two faces. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

VOLUME of POLYHEDRA USING a TETRAHEDRON BREAKUP We

VOLUME OF POLYHEDRA USING A TETRAHEDRON BREAKUP We have shown in an earlier note that any two dimensional polygon of N sides may be broken up into N-2 triangles T by drawing N-3 lines L connecting every second vertex. Thus the irregular pentagon shown has N=5,T=3, and L=2- With this information, one is at once led to the question-“ How can the volume of any polyhedron in 3D be determined using a set of smaller 3D volume elements”. These smaller 3D eelements are likely to be tetrahedra . This leads one to the conjecture that – A polyhedron with more four faces can have its volume represented by the sum of a certain number of sub-tetrahedra. The volume of any tetrahedron is given by the scalar triple product |V1xV2∙V3|/6, where the three Vs are vector representations of the three edges of the tetrahedron emanating from the same vertex. Here is a picture of one of these tetrahedra- Note that the base area of such a tetrahedron is given by |V1xV2]/2. When this area is multiplied by 1/3 of the height related to the third vector one finds the volume of any tetrahedron given by- x1 y1 z1 (V1xV2 ) V3 Abs Vol = x y z 6 6 2 2 2 x3 y3 z3 , where x,y, and z are the vector components. The next question which arises is how many tetrahedra are required to completely fill a polyhedron? We can arrive at an answer by looking at several different examples. Starting with one of the simplest examples consider the double-tetrahedron shown- It is clear that the entire volume can be generated by two equal volume tetrahedra whose vertexes are placed at [0,0,sqrt(2/3)] and [0,0,-sqrt(2/3)]. -

Crystalline Assemblies and Densest Packings of a Family of Truncated Tetrahedra and the Role of Directional Entropic Forces

Crystalline Assemblies and Densest Packings of a Family of Truncated Tetrahedra and the Role of Directional Entropic Forces Pablo F. Damasceno1*, Michael Engel2*, Sharon C. Glotzer1,2,3† 1Applied Physics Program, 2Department of Chemical Engineering, and 3Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA. * These authors contributed equally. † Corresponding author: [email protected] Dec 1, 2011 arXiv: 1109.1323v2 ACS Nano DOI: 10.1021/nn204012y ABSTRACT Polyhedra and their arrangements have intrigued humankind since the ancient Greeks and are today important motifs in condensed matter, with application to many classes of liquids and solids. Yet, little is known about the thermodynamically stable phases of polyhedrally-shaped building blocks, such as faceted nanoparticles and colloids. Although hard particles are known to organize due to entropy alone, and some unusual phases are reported in the literature, the role of entropic forces in connection with polyhedral shape is not well understood. Here, we study thermodynamic self-assembly of a family of truncated tetrahedra and report several atomic crystal isostructures, including diamond, β-tin, and high- pressure lithium, as the polyhedron shape varies from tetrahedral to octahedral. We compare our findings with the densest packings of the truncated tetrahedron family obtained by numerical compression and report a new space filling polyhedron, which has been overlooked in previous searches. Interestingly, the self-assembled structures differ from the densest packings. We show that the self-assembled crystal structures can be understood as a tendency for polyhedra to maximize face-to-face alignment, which can be generalized as directional entropic forces. -

The Truncated Icosahedron As an Inflatable Ball

https://doi.org/10.3311/PPar.12375 Creative Commons Attribution b |99 Periodica Polytechnica Architecture, 49(2), pp. 99–108, 2018 The Truncated Icosahedron as an Inflatable Ball Tibor Tarnai1, András Lengyel1* 1 Department of Structural Mechanics, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, H-1521 Budapest, P.O.B. 91, Hungary * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received: 09 April 2018, Accepted: 20 June 2018, Published online: 29 October 2018 Abstract In the late 1930s, an inflatable truncated icosahedral beach-ball was made such that its hexagonal faces were coloured with five different colours. This ball was an unnoticed invention. It appeared more than twenty years earlier than the first truncated icosahedral soccer ball. In connection with the colouring of this beach-ball, the present paper investigates the following problem: How many colourings of the dodecahedron with five colours exist such that all vertices of each face are coloured differently? The paper shows that four ways of colouring exist and refers to other colouring problems, pointing out a defect in the colouring of the original beach-ball. Keywords polyhedron, truncated icosahedron, compound of five tetrahedra, colouring of polyhedra, permutation, inflatable ball 1 Introduction Spherical forms play an important role in different fields – not even among the relics of the Romans who inherited of science and technology, and in different areas of every- many ball games from the Greeks. day life. For example, spherical domes are quite com- The Romans mainly used balls composed of equal mon in architecture, and spherical balls are used in most digonal panels, forming a regular hosohedron (Coxeter, 1973, ball games. -

Just (Isomorphic) Friends: Symmetry Groups of the Platonic Solids

Just (Isomorphic) Friends: Symmetry Groups of the Platonic Solids Seth Winger Stanford University|MATH 109 9 March 2012 1 Introduction The Platonic solids have been objects of interest to mankind for millennia. Each shape—five in total|is made up of congruent regular polygonal faces: the tetrahedron (four triangular sides), the cube (six square sides), the octahedron (eight triangular sides), the dodecahedron (twelve pentagonal sides), and the icosahedron (twenty triangular sides). They are prevalent in everything from Plato's philosophy, where he equates them to the four classical elements and a fifth heavenly aether, to middle schooler's role playing games, where Platonic dice determine charisma levels and who has to get the next refill of Mountain Dew. Figure 1: The five Platonic solids (http://geomag.elementfx.com) In this paper, we will examine the symmetry groups of these five solids, starting with the relatively simple case of the tetrahedron and moving on to the more complex shapes. The rotational symmetry groups of the solids share many similarities with permutation groups, and these relationships will be shown to be an isomorphism that can then be exploited when discussing the Platonic solids. The end goal is the most complex case: describing the symmetries of the icosahedron in terms of A5, the group of all sixty even permutations in the permutation group of degree 5. 2 The Tetrahedron Imagine a tetrahedral die, where each vertex is labeled 1, 2, 3, or 4. Two or three rolls of the die will show that rotations can induce permutations of the vertices|a different number may land face up on every throw, for example|but how many such rotations and permutations exist? There are two main categories of rotation in a tetrahedron: r, those around an axis that runs from a vertex of the solid to the centroid of the opposing face; and q, those around an axis that runs from midpoint to midpoint of opposing edges (see Figure 2). -

Are Your Polyhedra the Same As My Polyhedra?

Are Your Polyhedra the Same as My Polyhedra? Branko Gr¨unbaum 1 Introduction “Polyhedron” means different things to different people. There is very little in common between the meaning of the word in topology and in geometry. But even if we confine attention to geometry of the 3-dimensional Euclidean space – as we shall do from now on – “polyhedron” can mean either a solid (as in “Platonic solids”, convex polyhedron, and other contexts), or a surface (such as the polyhedral models constructed from cardboard using “nets”, which were introduced by Albrecht D¨urer [17] in 1525, or, in a more mod- ern version, by Aleksandrov [1]), or the 1-dimensional complex consisting of points (“vertices”) and line-segments (“edges”) organized in a suitable way into polygons (“faces”) subject to certain restrictions (“skeletal polyhedra”, diagrams of which have been presented first by Luca Pacioli [44] in 1498 and attributed to Leonardo da Vinci). The last alternative is the least usual one – but it is close to what seems to be the most useful approach to the theory of general polyhedra. Indeed, it does not restrict faces to be planar, and it makes possible to retrieve the other characterizations in circumstances in which they reasonably apply: If the faces of a “surface” polyhedron are sim- ple polygons, in most cases the polyhedron is unambiguously determined by the boundary circuits of the faces. And if the polyhedron itself is without selfintersections, then the “solid” can be found from the faces. These reasons, as well as some others, seem to warrant the choice of our approach. -

New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and Their Crystal Structures Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverria

New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverria To cite this version: Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverria. New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures. Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry, Wiley, 2010, 23 (11), pp.1080. 10.1002/poc.1735. hal-00589441 HAL Id: hal-00589441 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00589441 Submitted on 29 Apr 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures For Peer Review Journal: Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry Manuscript ID: POC-09-0305.R1 Wiley - Manuscript type: Research Article Date Submitted by the 06-Apr-2010 Author: Complete List of Authors: Alvarez, Santiago; Universitat de Barcelona, Departament de Quimica Inorganica Echeverria, Jorge; Universitat de Barcelona, Departament de Quimica Inorganica continuous shape measures, stereochemistry, shape maps, Keywords: polyhedranes http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/poc Page 1 of 20 Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures 11 12 Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverría 13 14 15 Departament de Química Inorgànica and Institut de Química Teòrica i Computacional, 16 Universitat de Barcelona, Martí i Franquès 1-11, 08028 Barcelona (Spain). -

![Math.MG] 25 Sep 2012 Oisb Ue N Ops,O Ae Folding](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3106/math-mg-25-sep-2012-oisb-ue-n-ops-o-ae-folding-1203106.webp)

Math.MG] 25 Sep 2012 Oisb Ue N Ops,O Ae Folding

Constructing the Cubus simus and the Dodecaedron simum via paper folding Urs Hartl and Klaudia Kwickert August 27, 2012 Abstract The archimedean solids Cubus simus (snub cube) and Dodecaedron simum (snub dodecahe- dron) cannot be constructed by ruler and compass. We explain that for general reasons their vertices can be constructed via paper folding on the faces of a cube, respectively dodecahedron, and we present explicit folding constructions. The construction of the Cubus simus is particularly elegant. We also review and prove the construction rules of the other Archimedean solids. Keywords: Archimedean solids Snub cube Snub dodecahedron Construction Paper folding · · · · Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 51M15, (51M20) Contents 1 Construction of platonic and archimedean solids 1 2 The Cubus simus constructed out of a cube 4 3 The Dodecaedron simum constructed out of a dodecahedron 7 A Verifying the construction rules from figures 2, 3, and 4. 11 References 13 1 Construction of platonic and archimedean solids arXiv:1202.0172v2 [math.MG] 25 Sep 2012 The archimedean solids were first described by Archimedes in a now-lost work and were later redis- covered a few times. They are convex polyhedra with regular polygons as faces and many symmetries, such that their symmetry group acts transitively on their vertices [AW86, Cro97]. They can be built by placing their vertices on the faces of a suitable platonic solid, a tetrahedron, a cube, an octahedron, a dodecahedron, or an icosahedron. In this article we discuss the constructibility of the archimedean solids by ruler and compass, or paper folding. All the platonic solids can be constructed by ruler and compass. -

The Platonic Solids

The Platonic Solids William Wu [email protected] March 12 2004 The tetrahedron, the cube, the octahedron, the dodecahedron, and the icosahedron. From a ¯rst glance, one immediately notices that the Platonic Solids exhibit remarkable symmetry. They are the only convex polyhedra for which the same same regular polygon is used for each face, and the same number of faces meet at each vertex. Their symmetries are aesthetically pleasing, like those of stones cut by a jeweler. We can further enhance our appreciation of these solids by examining them under the lenses of group theory { the mathematical study of symmetry. This article will discuss the group symmetries of the Platonic solids using a variety of concepts, including rotations, reflections, permutations, matrix groups, duality, homomorphisms, and representations. 1 The Tetrahedron 1.1 Rotations We will begin by studying the symmetries of the tetrahedron. If we ¯rst restrict ourselves to rotational symmetries, we ask, \In what ways can the tetrahedron be rotated such that the result appears identical to what we started with?" The answer is best elucidated with the 1 Figure 1: The Tetrahedron: Identity Permutation aid of Figure 1. First consider the rotational axis OA, which runs from the topmost vertex through the center of the base. Note that we can repeatedly rotate the tetrahedron about 360 OA by 3 = 120 degrees to ¯nd two new symmetries. Since each face of the tetrahedron can be pierced with an axis in this fashion, we have found 4 £ 2 = 8 new symmetries. Figure 2: The Tetrahedron: Permutation (14)(23) Now consider rotational axis OB, which runs from the midpoint of one edge to the midpoint of the opposite edge. -

![[ENTRY POLYHEDRA] Authors: Oliver Knill: December 2000 Source: Translated Into This Format from Data Given In](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6670/entry-polyhedra-authors-oliver-knill-december-2000-source-translated-into-this-format-from-data-given-in-1456670.webp)

[ENTRY POLYHEDRA] Authors: Oliver Knill: December 2000 Source: Translated Into This Format from Data Given In

ENTRY POLYHEDRA [ENTRY POLYHEDRA] Authors: Oliver Knill: December 2000 Source: Translated into this format from data given in http://netlib.bell-labs.com/netlib tetrahedron The [tetrahedron] is a polyhedron with 4 vertices and 4 faces. The dual polyhedron is called tetrahedron. cube The [cube] is a polyhedron with 8 vertices and 6 faces. The dual polyhedron is called octahedron. hexahedron The [hexahedron] is a polyhedron with 8 vertices and 6 faces. The dual polyhedron is called octahedron. octahedron The [octahedron] is a polyhedron with 6 vertices and 8 faces. The dual polyhedron is called cube. dodecahedron The [dodecahedron] is a polyhedron with 20 vertices and 12 faces. The dual polyhedron is called icosahedron. icosahedron The [icosahedron] is a polyhedron with 12 vertices and 20 faces. The dual polyhedron is called dodecahedron. small stellated dodecahedron The [small stellated dodecahedron] is a polyhedron with 12 vertices and 12 faces. The dual polyhedron is called great dodecahedron. great dodecahedron The [great dodecahedron] is a polyhedron with 12 vertices and 12 faces. The dual polyhedron is called small stellated dodecahedron. great stellated dodecahedron The [great stellated dodecahedron] is a polyhedron with 20 vertices and 12 faces. The dual polyhedron is called great icosahedron. great icosahedron The [great icosahedron] is a polyhedron with 12 vertices and 20 faces. The dual polyhedron is called great stellated dodecahedron. truncated tetrahedron The [truncated tetrahedron] is a polyhedron with 12 vertices and 8 faces. The dual polyhedron is called triakis tetrahedron. cuboctahedron The [cuboctahedron] is a polyhedron with 12 vertices and 14 faces. The dual polyhedron is called rhombic dodecahedron. -

Chapter 2 Figures and Shapes 2.1 Polyhedron in N-Dimension in Linear

Chapter 2 Figures and Shapes 2.1 Polyhedron in n-dimension In linear programming we know about the simplex method which is so named because the feasible region can be decomposed into simplexes. A zero-dimensional simplex is a point, an 1D simplex is a straight line segment, a 2D simplex is a triangle, a 3D simplex is a tetrahedron. In general, a n-dimensional simplex has n+1 vertices not all contained in a (n-1)- dimensional hyperplane. Therefore simplex is the simplest building block in the space it belongs. An n-dimensional polyhedron can be constructed from simplexes with only possible common face as their intersections. Such a definition is a bit vague and such a figure need not be connected. Connected polyhedron is the prototype of a closed manifold. We may use vertices, edges and faces (hyperplanes) to define a polyhedron. A polyhedron is convex if all convex linear combinations of the vertices Vi are inside itself, i.e. i Vi is contained inside for all i 0 and all _ i i 1. i If a polyhedron is not convex, then the smallest convex set which contains it is called the convex hull of the polyhedron. Separating hyperplane Theorem For any given point outside a convex set, there exists a hyperplane with this given point on one side of it and the entire convex set on the other. Proof: Because the given point will be outside one of the supporting hyperplanes of the convex set. 2.2 Platonic Solids Known to Plato (about 500 B.C.) and explained in the Elements (Book XIII) of Euclid (about 300 B.C.), these solids are governed by the rules that the faces are the regular polygons of a single species and the corners (vertices) are all alike.