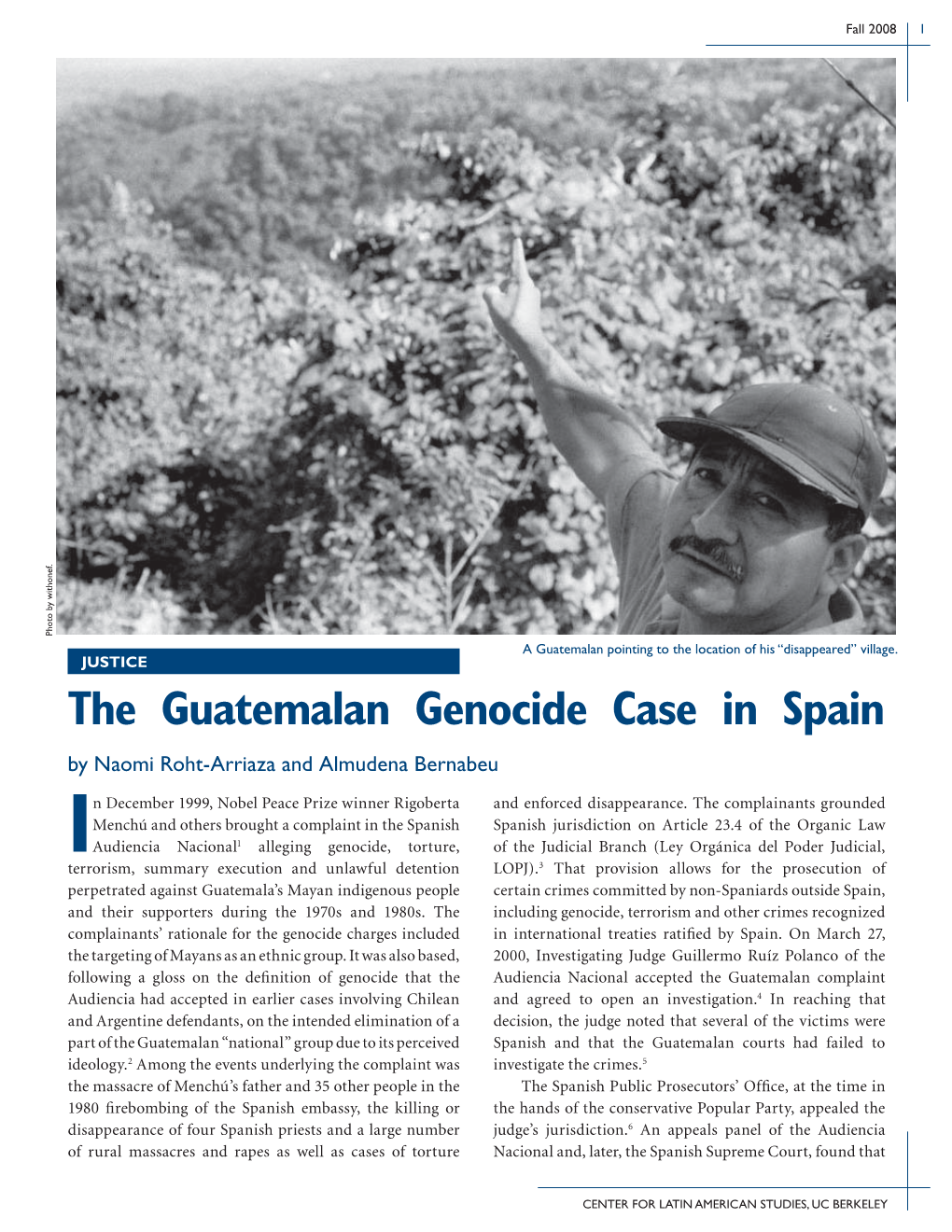

The Guatemala Genocide Case in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greco Eval IV Rep (2013) 5E Final Spain PUBLIC

F O U R T Adoption: 6 December 2013 Public Publication: 15 January 2014 Greco Eval IV Rep (2013) 5E H E V FOURTH EVALUATION ROUND A L Corruption prevention in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors U A T I O EVALUATION REPORT N SPAIN R O Adopted by GRECO at its 62nd Plenary Meeting U (Strasbourg, 2-6 December 2013) N D 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 3 I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 6 II. CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................................. 8 III. CORRUPTION PREVENTION IN RESPECT OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT ................................................ 10 OVERVIEW OF THE PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEM ............................................................................................................... 10 TRANSPARENCY OF THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS ............................................................................................................. 11 REMUNERATION AND ECONOMIC BENEFITS ................................................................................................................. 12 ETHICAL PRINCIPLES AND RULES OF CONDUCT .............................................................................................................. 12 CONFLICTS OF INTEREST ......................................................................................................................................... -

Seven Theses on Spanish Justice to Understand the Prosecution of Judge Garzón

Oñati Socio-Legal Series, v. 1, n. 9 (2011) – Autonomy and Heteronomy of the Judiciary in Europe ISSN: 2079-5971 Seven Theses on Spanish Justice to understand the Prosecution of Judge Garzón ∗ JOXERRAMON BENGOETXEA “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” (Hamlet) Abstract Judges may not decide cases as they wish, they are subject to the law they are entrusted to apply, a law made by the legislator (a feature of heteronomy). But in doing so, they do not take any instruction from any other power or instance (this contributes to their independence or autonomy). Sometimes, they apply the law of the land taking into account the norms and principles of other, international, supranational, even transnational systems. In such cases of conform interpretation, again, they perform a delicate balance between autonomy (domestic legal order and domestic culture of legal interpretation) and heteronomy (external legal order and culture of interpretation). There are common shared aspects of Justice in the Member States of the EU, but, this contribution explores some, perhaps the most salient, features of Spanish Justice in this wider European context. They are not exclusive to Spain, but they way they combine and interact, and their intensity is quite uniquely Spanish. These are seven theses about Justice in Spain, which combine in unique ways as can be seen in the infamous Garzón case, discussed in detail. Key words Spanish Judiciary; Judicial statistics; Transition in Spain; Sociology of the Judiciary; Consejo General del Poder Judicial; Politicisation of Justice; Judicialisation of Politics; Spanish Constitutional Court; Spanish Supreme Court; Audiencia Nacional; Acusación Pública; Judge Garzón; Basque Political Parties; Clashes between Judicial Hierarchies ∗ Universidad del País Vasco – Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, [email protected] This research has been carried out within the framework of a research project on Fundamental Rights After 1 Lisbon (der2010-19715, juri) financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. -

Download File

A War of Proper Names: The Politics of Naming, Indigenous Insurrection, and Genocidal Violence During Guatemala’s Civil War. Juan Carlos Mazariegos Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2019 Juan Carlos Mazariegos All Rights Reserved Abstract A War of Proper Names: The Politics of Naming, Indigenous Insurrection, and Genocidal Violence During Guatemala’s Civil War During the Guatemalan civil war (1962-1996), different forms of anonymity enabled members of the organizations of the social movement, revolutionary militants, and guerrilla combatants to address the popular classes and rural majorities, against the backdrop of generalized militarization and state repression. Pseudonyms and anonymous collective action, likewise, acquired political centrality for revolutionary politics against a state that sustained and was symbolically co-constituted by forms of proper naming that signify class and racial position, patriarchy, and ethnic difference. Between 1979 and 1981, at the highest peak of mass mobilizations and insurgent military actions, the symbolic constitution of the Guatemalan state was radically challenged and contested. From the perspective of the state’s elites and military high command, that situation was perceived as one of crisis; and between 1981 and 1983, it led to a relatively brief period of massacres against indigenous communities of the central and western highlands, where the guerrillas had been operating since 1973. Despite its long duration, by 1983 the fate of the civil war was sealed with massive violence. Although others have recognized, albeit marginally, the relevance of the politics of naming during Guatemala’s civil war, few have paid attention to the relationship between the state’s symbolic structure of signification and desire, its historical formation, and the dynamics of anonymous collective action and revolutionary pseudonymity during the war. -

Armen Sarkissian • Adama Dieng • Henry Theriault • Fernand De Varennes • Mô Bleeker • Kyriakos Kyriakou-Hadjiyianni •

GENOCIDE PREVENTION THROUGH EDUCATION 9-11 DECEMBER 2018 YEREVAN • ARMENIA ORGANIZERS Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia WITH SUPPORT OF IN COOPERATION WITH UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON GENOCIDE PREVENTION AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT TABLE of CONTENTS 9 Message from the Organizers 12 PROGRAM 9-11 December 2018 16 HIGH LEVEL SEGMENT • Zohrab Mnatsakanyan • Armen Sarkissian • Adama Dieng • Henry Theriault • Fernand de Varennes • Mô Bleeker • Kyriakos Kyriakou-Hadjiyianni • 47 PLENARY Dunja SESSION: Mijatović 70th Anniversaries of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the Uni- versal Declaration of Human Rights. 69 PANEL ONE: Supporting Genocide Prevention through Perpetua- tion of Remembrance Days of Genocide Victims. 101 PANEL TWO: New Approaches to Education and Art about Geno- cide and its Prevention. 123 PANEL THREE: Combating Genocide Denial and Propaganda of Xenophobia. 161 PANEL FOUR: The Role of Education and Awareness Raising in the Prevention of the Crime of Genocide. 190 PREVENTION 194 SIDE EVENTS 200 AFTERWORD 10 MESSAGE FROM THE ORGANIZERS he 3rd Global Forum against the Crime of Genocide was held in 2018 and was dedicated to the issues of genocide preven- T tion through education, culture and museums. It examined the challenges and opportunities, experiences and perspectives of the genocide education. This book encompasses presentations that address among other things the role of genocide museums, memorial sites and institutes for perpetuation of remembrance, as well as such complex issues as - tings in which reconciliation, memory, and empathy help to restore aworking modicum with of groups-in-conflicttrust and open communication; in non-traditional combatting educational genocide set denial and propaganda of xenophobia. -

“Behind-The-Table” Conflicts in the Failed Negotiation for a Referendum for the Independence of Catalonia

“Behind-the-Table” Conflicts in the Failed Negotiation for a Referendum for the Independence of Catalonia Oriol Valentí i Vidal*∗ Spain is facing its most profound constitutional crisis since democracy was restored in 1978. After years of escalating political conflict, the Catalan government announced it would organize an independence referendum on October 1, 2017, an outcome that the Spanish government vowed to block. This article represents, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the first scholarly examination to date from a negotiation theory perspective of the events that hindered political dialogue between both governments regarding the organization of the secession vote. It applies Robert H. Mnookin’s insights on internal conflicts to identify the apparent paradox that characterized this conflict: while it was arguably in the best interest of most Catalans and Spaniards to know the nature and extent of the political relationship that Catalonia desired with Spain, their governments were nevertheless unable to negotiate the terms and conditions of a legal, mutually agreed upon referendum to achieve this result. This article will argue that one possible explanation for this paradox lies in the “behind-the-table” *Attorney; Lecturer in Law, Barcelona School of Management (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) as of February 2018. LL.M. ‘17, Harvard Law School; B.B.A. ‘13 and LL.B. ‘11, Universitat Pompeu Fabra; Diploma in Legal Studies ‘10, University of Oxford. This article reflects my own personal views and has been written under my sole responsibility. As such, it has not been written under the instructions of any professional or academic organization in which I render my services. -

The Guatemala Genocide Cases: Universal Jurisdiction and Its Limits

© The Guatemala Genocide Cases: Universal Jurisdiction and Its Limits by Paul “Woody” Scott* INTRODUCTION Systematic murder, genocide, torture, terror and cruelty – all are words used to describe the campaigns of Guatemalan leaders, including President Jose Efrain Rios Montt, directed toward the indigenous Mayans in the Guatemalan campo. The United Nations-backed Truth Commission concludes that the state carried out deliberate acts of genocide against the Mayan indigenous populations.1 Since Julio Cesar Mendez Montenegro took Guatemalan presidential office in 1966, Guatemala was involved in a bloody civil war between the army and guerrilla groups located in the Guatemalan countryside. The bloodshed escalated as Montt, a fundamentalist Christian minister, rose to power in 1982 after taking part in a coup d’état and becoming the de facto president of Guatemala. He was in power for just sixteen months, considered by many to be the bloodiest period of Guatemala’s history.2 Under his sixteen-month rule, more than 200,000 people were victims of homicide or forced kidnappings, 83% of whom were of indigenous Mayan origin. Indigenous Mayans were targeted, killed, tortured, raped, and * Paul “Woody” Scott is an associate attorney with Jeri Flynn & Associates in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His practice is primarily immigration law and criminal defense, specializing in defending immigrants charged with criminal offenses, and deportation defense. He was born in San Pedro Sula, Honduras and moved to the United States at a very early age. He is fluent in both English and Spanish. 1 United Nations Office for Project Services [UNOPS], Commission for Historical Clarification [CEH], Conclusions and Recommendations, GUATEMALA, MEMORIA DEL SILENCIO [hereinafter, GUATEMALA, MEMORY OF SILENCE], Volume V, ¶ 26 (1999). -

Bocg-12-Cg-A-282 Boletín Oficial De Las Cortes Generales Sección Cortes Generales

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LAS CORTES GENERALES SECCIÓN CORTES GENERALES XII LEGISLATURA Serie A: ACTIVIDADES PARLAMENTARIAS 27 de marzo de 2019 Núm. 282 Pág. 1 Composición y organización de órganos mixtos y conjuntos DISOLUCIÓN DE LA LEGISLATURA 420/000079 (CD) Relaciones de iniciativas caducadas y de iniciativas trasladadas a las Cámaras que se 561/000008 (S) constituyan en la XIII Legislatura. La Mesa de la Diputación Permanente del Congreso de los Diputados, en su reunión del día 13 de marzo de 2019, acordó, una vez producida la disolución de la Cámara, la publicación de las relaciones siguientes relativas a Comisiones Mixtas: A) Relación de iniciativas ya calificadas que se hallaban en tramitación en el momento de la disolución y que han caducado como consecuencia de ésta. B) Relación de iniciativas que se trasladan a las Cámaras que se constituyan en la XIII Legislatura. En ejecución de dicho acuerdo, se ordena la publicación. Palacio del Congreso de los Diputados, 13 de marzo de 2019.—P.D. El Letrado Mayor de las Cortes Generales, Carlos Gutiérrez Vicén. cve: BOCG-12-CG-A-282 BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LAS CORTES GENERALES SECCIÓN CORTES GENERALES Serie A Núm. 282 27 de marzo de 2019 Pág. 2 A) RELACIÓN DE INICIATIVAS YA CALIFICADAS QUE SE HALLABAN EN TRAMITACIÓN EN EL MOMENTO DE LA DISOLUCIÓN Y QUE HAN CADUCADO COMO CONSECUENCIA DE ÉSTA 1. Subcomisiones y Ponencias. Núm. expte.: 154/000001/0000 (CD) 573/000001/0000 (S) Autor: Comisión Mixta para la Unión Europea. Objeto: Ponencia para el estudio de las consecuencias derivadas de la salida del Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda del Norte de la Unión Europea. -

LATIN AMERICA Catalonia Not Well OE Watch Commentary: Barcelona Continues to Be a Political Tinderbox

LATIN AMERICA Catalonia Not Well OE Watch Commentary: Barcelona continues to be a political tinderbox. The most recent disturbances were investigated by the Audiencia Nacional, a tribunal with appellate and trial competence, with jurisdiction throughout Spain. It has its own investigative capacity as well. It may be a particularly Spanish institution, established in 1977 during the transition after Franco’s death in 1975. It is intended to consider terrorism, drug-trafficking and other major organized criminal activities of that reach, including rebellion, while hopefully avoiding prosecutorial excesses. As the first accompanying passage notes, its report of the disturbances in Catalonia finds what some Spanish take as a flash of the obvious -- that they were the creature of a radical political organization, not just a public reaction. Understanding the order of battle of radical leftist opposition organization in Spain is a difficult task, however, given the overlap of mainstream and locally governing parties and social organizations and competing goals among those entities. The second accompanying reference is of a completely separate yet completely related issue – Spain’s central government, led by socialist Pedro Sánchez is acting to control an effort by the Catalonian government to create an independent database of Catalonian citizens for purposes of citizen identification and control. The intention is to further Catalonian independence, the contraption even being called the Catalonian Digital Republic. The Spanish government in Madrid is not having it. The tiff, however, is a clear example of the overlap of physical territoriality and cyber-struggle. The third reference evidences another, background problem in the application of violent forms of struggle. -

No Justice, No Peace: Accountability for Rape and Gender-Based Violence in the Former Yugoslavia Women in the Law Project

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 5 | Number 1 Article 5 1-1-1994 No Justice, No Peace: Accountability for Rape and Gender-Based Violence in the Former Yugoslavia Women in the Law Project Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Recommended Citation Women in the Law Project, No Justice, No Peace: Accountability for Rape and Gender-Based Violence in the Former Yugoslavia, 5 Hastings Women's L.J. 89 (1994). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol5/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ii!. No Justice, No Peace: Accountability for Rape and Gender-Based Violence in the Former Yugoslavia Based on a Mission of the Women in the Law Project of the International Human Rights Law Group* PREFACE The Women in the Law Project of the International Human Rights Law Group (Law Group) sponsored a delegation to the former Yugoslavia from February 14 to 22, 1993. The delegation, which was also endorsed by the Bar Association of San Francisco, had two principal objectives. First, the delegation provided training in human rights fact-finding methodology to local organizations documenting rape and other violations of international law committed in the context of the armed conflict in Bos nia-Herzegovina (Bosnia) and in Croatia. This part of the delegation's activities, undertaken in consultation with the United Nations Commission of Experts, I sought to enhance the thoroughness of local documentation * Delegation Members: Laurel Fletcher, Esq.; Professor Karen Musalo; Professor Diane Orentlicher, Chair; Kathleen Pratt, Esq. -

1985-Nicaragua-Abuses Against Civilians by Counterrevolutionaries

REPORT and Prof. MICHAEL J. GLENNON to the INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW GROUP and the WASHINGTON OFFICE ON LATIN AMERICA concerning ---- ---- ---- ABUSES AGAINST CIVILIANS BY COUNTERREVOLUTIONARIES OPERATING IN NICARAGUA APRIL 1985 Copies of this report are available for $6.00 from the following organizations: Washington Office on Latin America 110 Maryland Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20002 (202) 544-8045 International Human Rights Law Group 1346 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington D.C. 20036 (202) 659-5023 Q 1985 by the Washington Office on Latin America and the International Human Rights Law Group All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States TABLE OF CONTENTS -Page Preface...................................... i Statement of Sponsoring Organizations.. ...... iii Repor t of Donald T. Fox and Michael J. Glennon A. Introduction............................. 1 B. Background.............. ................. 3 C. Methodology........ ....................... 7 D. Findings .................................. 13 1. Sandinistas........................... 13 2. Contras............................... 14 3. United States Government .............. 20 F. Recommendations........................... 24 G. Final Thoughts.............. ............... 25 Appendices I. Terms of Reference and Biographies of Mr. Fox and Professor Glennon 11. Itinerary 111. Statements of Selected Individuals IV. Common Article 111 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 PREFACE As part of their respective programs, the Inter national Human Rights Law Gcoup (Law G~oup)and the Washington Off ice on Latin America (WOLA) organized a delegation to visit Nicaragua to investigate and to report on allegations of abuses against the civilian population by the counterrevolutionary forces (Contras) f'ighting the Nicar aguan government. The delegation consisted of &. Donald FOX, senior partner in the New York law firm of FOX, Glynn and Melamed, and Mr. Michael Glennon, professor at the University of Cincinnati Law. -

Evidentiary Challenges in Universal Jurisdiction Cases

Evidentiary challenges in universal jurisdiction cases Universal Jurisdiction Annual Review 2019 #UJAR 1 Photo credit: UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata This publication benefted from the generous support of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, the Oak Foundation and the City of Geneva. TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 FOREWORD 8 BUILDING ON SHIFTING SANDS: EVIDENTIARY CHALLENGES IN UNIVERSAL JURISDICTION CASES 11 KEY FINDINGS 12 CASES OF 2018 Argentina 13 VICTIMS DEMAND THE TRUTH ABOUT THE FRANCO DICTATORSHIP 15 ARGENTINIAN PROSECUTORS CONSIDER CHARGES AGAINST CROWN PRINCE Austria 16 SUPREME COURT OVERTURNS JUDGMENT FOR WAR CRIMES IN SYRIA 17 INVESTIGATION OPENS AGAINST OFFICIALS FROM THE AL-ASSAD REGIME Belgium 18 FIVE RWANDANS TO STAND TRIAL FOR GENOCIDE 19 AUTHORITIES ISSUE THEIR FIRST INDICTMENT ON THE 1989 LIBERIAN WAR Finland 20 WAR CRIMES TRIAL RAISES TECHNICAL CHALLENGES 22 FORMER IRAQI SOLDIER SENTENCED FOR WAR CRIMES France ONGOING INVESTIGATIONS ON SYRIA 23 THREE INTERNATIONAL ARREST WARRANTS TARGET HIGH-RANKING AL-ASSAD REGIME OFFICIALS 24 SYRIAN ARMY BOMBARDMENT TARGETING JOURNALISTS IN HOMS 25 STRUCTURAL INVESTIGATION BASED ON INSIDER PHOTOS 26 FIRST IN FRANCE: COMPANY INDICTED FOR CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY 28 FRANCE REVOKES REFUGEE STATUS OF MASS MASSACRE SUSPECT 29 SAUDI CROWN PRINCE UNDER INVESTIGATION 30 INVESTIGATION OPENS ON BENGAZHY SIEGE 3 31 A EUROPEAN COLLABORATION: SWISS NGO SEEKS A WARLORD’S PROSECUTION IN FRANCE 32 IS SELLING SPYING DEVICE TO AL-ASSAD’S REGIME COMPLICITY IN TORTURE? RWANDAN TRIALS IN -

Gambling with the Psyche: Does Prosecuting Human Rights Violators Console Their Victims?

VOLUME 46, NUMBER 2, SUMMER 2005 Gambling with the Psyche: Does Prosecuting Human Rights Violators Console Their Victims? Jamie O'Connell* INTRODUCTION Legal action against those accused of committing brutal violations of hu- man rights has flourished in the last decade. Saddam Hussein awaits trial in Iraq.' Augusto Pinochet, Chile's former military leader, has been pursued by European and Chilean prosecuting judges since Spain's Balthasar Garz6n sought his extradition for murder in October 1998.2 Meanwhile, at the Interna- tional Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia ("ICTY"), Slobodan Mil- 3 osevic is preparing his defense against charges of genocide and war crimes. Even U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, with other senior officials, has been accused in a privately filed criminal complaint in Germany of being responsible for the torture of prisoners held in Iraq.4 Such legal actions were almost unimaginable a decade ago. These are only the most prominent cases. A dozen senior Baathist officials face prosecution by Iraq's new government. 5 In Argentina, a 2001 court rul- ing abrogated laws giving immunity to military officers who oversaw and participated in the kidnapping and secret execution ("disappearance") of as * Clinical Advocacy Fellow, Human Rights Program, Harvard Law School; J.D., Yale Law School, 2002. I could not have written this Article without help from therapists and lawyers who work directly with survivors of traumatic violations of human rights. Mary Fabri, Rosa Garcia-Peltoniemi, Jerry Gray, Hank Greenspan, Judith Herman, Douglas Johnson, Dori Laub, Beth Stephens, Noga Tarnopolsky, and Alan Tieger gave me insights unavailable in any published source I could find.