A Str a Teg Ic Rev Ie W of G Iv in G in Lo Ndon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underclass, Overclass, Ruling Class, Supernova Class1

EIGHT Underclass, overclass, ruling class, supernova class1 Danny Dorling Introduction One man in his mid-thirties hoped that his six-figure income would grow rapidly, and admitted that his assets would be valued at nearly a million pounds. He held strong views about poverty. “There is no poverty. Now you can get money from the state. People don’t even have to go to work. You don’t have to put up with working in an unrewarding situation.” He strongly disagreed with the propositions that the gap between rich and poor was too wide and that the rich should be more highly taxed. He strongly opposed the idea of putting limits on “some people’s expensive way of living” to reduce poverty and disagreed with the statement that a lot of people entitled to claim benefits do not claim them. Finally, he strongly agreed that cuts in public services like health and education could be made without increasing the number of people in poverty and that, if there was any poverty, it was more likely to be reduced by increasing Britain’s wealth than by making incomes more equal. (Peter Townsend, describing the views of one of the new overclass of London, recorded in 1985-86; see Townsend, 1993, p 109) By 2010 one in ten of all Londoners had the wealth of the man who Peter had described some 25 years earlier as being part of a tiny elite 155 fighting poverty, inequality and social injustice (see Hills et al, 2010). The Hills inquiry into inequality revealed that one in ten Londoners now have wealth of nearly a million pounds, some 273 times the wealth of the poorest tenth of today’s Londoners. -

Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report

Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report AUTHOR: 11/18 MARINELLA CAPRIATI, DPHIL 1 — Founders Pledge Animal Welfare Executive Summary By supporting increased use of evidence in the governments of low- and middle-income countries, donors can dramatically increase their impact on the lives of people living in poverty. This report explores how focusing on evidence-based policy provides an opportunity for leverage, and presents the most promising organisation we identified in this area. A high-risk/high-return opportunity for leverage In the 2013 report ‘The State of the Poor’, the World Bank reported that, as of 2010, roughly 83% of people in extreme poverty lived in countries classified as ‘lower-middle income’ or below. By far the most resources spent on tackling poverty come from local governments. American think tank the Brookings Institution found that, in 2011, $2.3 trillion of the $2.8 trillion spent on financing development came from domestic government revenues in the countries affected. There are often large differences in the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of social programs— the amount of good done per dollar spent can vary significantly across programs. Employing evidence allows us to identify the most cost-effective social programs. This is useful information for donors choosing which charity to support, but also for governments choosing which programs to implement, and how. This suggests that employing philanthropic funding to improve the effectiveness of policymaking in low- and middle-income countries is likely to constitute an exceptional opportunity for leverage: by supporting the production and use of evidence in low- and middle-income countries, donors can potentially enable policy makers to implement more effective policies, thereby reaching many more people than direct interventions. -

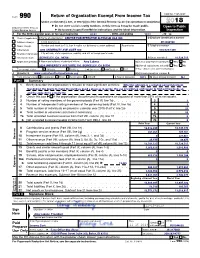

2018 ▶ Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2018 ▶ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2018 calendar year, or tax year beginning01/01 , 2018, and ending12/31 , 20 18 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization CENTRE FOR EFFECTIVE ALTRUISM USA INC D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 47-1988398 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300 510-725-1395 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return BERKELEY, CA, 94704 G Gross receipts $ 10,524,715 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: Amy Labenz H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300, BERKELEY, CA 94704 H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: ✔ 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ◀ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: ▶ www.centerforeffectivealtruism.org H(c) Group exemption number ▶ K Form of organization: ✔ Corporation Trust Association Other ▶ L Year of formation: 2013 M State of legal domicile: NJ Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: Effective altruism is a growing social movement founded on the desire to make the world as good a place as it can be, the use of evidence and reason to find out how to do so, and the audacity to actually try. -

Climate Change Cause Area Report

Climate Change Cause Area Report AUTHOR: LAST UPDATED 05/2018 JOHN HALSTEAD, DPHIL Executive Summary Climate change is an unprecedented problem requiring unprecedented global cooperation. However, global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have failed thus far. This report discusses the science, politics, and economics of climate change, and what philanthropists can do to help improve progress on tackling climate change. 1. The climate challenge and progress so far The first section provides an overview of the science of climate change, what needs to be done in order to avoid dangerous warming, and progress so far. One can mark the advent of the Industrial Revolution with James Watt’s patent for the steam engine in 1769. Until that point, for most of human history concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere had hovered around 280 parts per million (ppm). They recently passed 400 ppm for the first time in hundreds of thousands of years. This has been driven by the massive increase in deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution. CO2 and other greenhouse gases, such as methane, remain in the atmosphere and trap some of the heat leaving the planet, causing global warming. The metric of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) expresses the warming effect of all greenhouse gases in terms of the warming effect of CO2. The challenge facing humanity is not to reduce emissions rates to a lower level: if emissions continue at a constant (even low) positive rate, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gas concentrations will continue to increase and so will global temperatures. -

Farm Animal Funders Briefings

BRIEFING SERIES February, 2019 v1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals 2 Supporting Alternative Foods To Farmed Animal Products 4 Veg Advocacy 7 Corporate Campaigns For Welfare Reforms 9 Fishes 12 Legal and Legislative Methods 13 A Global Perspective on Farmed Animal Advocacy 15 Shallow Review: Increasing Donations Through Your Donation 19 2 Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals How Much To Give? There are a number of approaches to how much to give, Why Give? including: For the world: There are over 100 hundred billion farmed animals alive at any moment in conditions that Giving what you don’t need cause severe suffering, that number has been increasing over time and is projected to continue to do so. Consuming animal products is associated with many x % Pledging a set percentage negative health outcomes and animal agriculture is a chief cause of environmental degradation—causing approximately 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. % Giving to reach a personal best For you: Giving activates the brain’s reward centers, Some people give everything above what is necessary to resulting in increased life satisfaction and happiness. satisfy their needs, in part because of evidence that high levels of income have diminishing returns on wellbeing. How Can We Help Identify Cost-effective Funding Thousands of people (including some of the wealthiest) How To Give? Opportunities? publicly pledge some set percentage for giving. Pledging could increase your commitment to giving, further Effective giving is important because top Farmed Animal Funders release briefings and research connect you with a giving community, and inspire others. giving options are plausibly many times more different promising areas. -

Top Wealth Shares in the UK Over More Than a Century*

TOP WEALTH SHARES IN THE UK OVER MORE THAN A CEN TURY Facundo Alvaredo Anthony B Atkinson Salvatore Morelli INET Oxford WorkinG Paper no. 2017-01 19 December 2016 Employment, Equity & Growth Programme Top wealth shares in the UK over more than a century* Facundo Alvaredo Paris School of Economics, INET at the Oxford Martin School and Conicet Anthony B Atkinson Nuffield College, London School of Economics, and INET at the Oxford Martin School Salvatore Morelli CSEF – University of Naples “Federico II” and INET at the Oxford Martin School This version: 19 December 2016 Abstract Recent research highlighted controversy about the evolution of concentration of personal wealth. In this paper we provide new evidence about the long-run evolution of top wealth shares for the United Kingdom. The new series covers a long period – from 1895 to the present – and has a different point of departure from the previous literature: the distribution of estates left at death. We find that the application to the estate data of mortality multipliers to yield estimates of wealth among the living does not substantially change the degree of concentration over much of the period both, in the UK and US, allowing inferences to be made for years when this method cannot be applied. The results show that wealth concentration in the UK remained relatively constant during the first wave of globalization, but then decreased dramatically in the period from 1914 to 1979. The UK went from being more unequal in terms of wealth than the US to being less unequal. However, the decline in UK wealth concentration came to an end around 1980, and since then there is evidence of an increase in top shares, notably in the distribution of wealth excluding housing in recent years. -

A Study of UK Household Wealth Through Empirical Analysis and a Non-Linear Kesten Process

A Study of UK Household Wealth through Empirical Analysis and a Non-linear Kesten Process Samuel Forbes∗ Stefan Grosskinsky† July 2021 Abstract We study the wealth distribution of UK households through a detailed analysis of data from wealth surveys and rich lists, and propose a non-linear Kesten process to model the dynamics of household wealth. The main features of our model are that we focus on wealth growth and disregard exchange, and that the rate of return on wealth is increasing with wealth. The linear case with wealth-independent return rate has been well studied, leading to a log-normal wealth distribution in the long time limit which is essentially independent of initial conditions. We find through theoretical analysis and simulations that the non-linearity in our model leads to more realistic power-law tails, and can explain an apparent two-tailed structure in the empirical wealth distribution of the UK and other countries. Other realistic features of our model include an increase in inequality over time, and a stronger dependence on initial conditions compared to linear models. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Alexander Karalis Isaac and Colm Connaughton for their helpful discussions on this work. S. Forbes would also like to acknowledge financial support from EPSRC through grant EP/L015374/1. arXiv:2107.02169v1 [econ.TH] 5 Jul 2021 ∗[email protected] †[email protected] 1 1 Introduction The dynamics of wealth and income inequality is a subject of increasing research interest and public debate, encapsulated by major works such as Piketty's `Capital in the 21st Century' [33]. -

Author: Sjir Hoeijmakers, Msc Last Updated 05/2019

AUTHOR: LAST UPDATED SJIR HOEIJMAKERS, MSC 05/2019 1. Women’s empowerment One hundred and four countries still have laws preventing women from working in specific jobs; only 56% of women giving birth in Africa deliver in a health facility; and at least 35% of women worldwide have experienced some form of physical or sexual violence. These are just some of the challenges that women and girls around the globe face today. In this report, we focus on women’s empowerment, by which we mean improving the lives of women and girls. We researched charity programmes aimed at women’s empowerment to find those that most cost-effectively improve the lives of women and girls. As a heuristic for finding the most cost- effective interventions, we chose to focus on programmes aimed at low- and middle-income countries. 2. Our process We used a top-down approach to select charities. First, we categorised women’s empowerment in low- and middle-income countries into twelve subfields. We then reviewed literature and interviewed twenty experts in these subfields. This yielded a shortlist of eleven promising interventions across subfields, including the graduation approach to combat extreme poverty, empowerment-self-defence courses to prevent sexual violence, and interpersonal group therapy to treat depression. With this shortlist, we began evaluating charities. We started with a longlist of 163 women’s- empowerment charities, and narrowed it down to a shortlist of 15 charities based on our intervention research and a quick scan of organisational strength. We then compared the shortlisted organisations using more detailed information on both cost-effectiveness and strength of evidence. -

Risks of Space Colonization

Risks of space colonization Marko Kovic∗ July 2020 Abstract Space colonization is humankind's best bet for long-term survival. This makes the expected moral value of space colonization immense. However, colonizing space also creates risks | risks whose potential harm could easily overshadow all the benefits of humankind's long- term future. In this article, I present a preliminary overview of some major risks of space colonization: Prioritization risks, aberration risks, and conflict risks. Each of these risk types contains risks that can create enormous disvalue; in some cases orders of magnitude more disvalue than all the potential positive value humankind could have. From a (weakly) negative, suffering-focused utilitarian view, we there- fore have the obligation to mitigate space colonization-related risks and make space colonization as safe as possible. In order to do so, we need to start working on real-world space colonization governance. Given the near total lack of progress in the domain of space gover- nance in recent decades, however, it is uncertain whether meaningful space colonization governance can be established in the near future, and before it is too late. ∗[email protected] 1 1 Introduction: The value of colonizing space Space colonization, the establishment of permanent human habitats beyond Earth, has been the object of both popular speculation and scientific inquiry for decades. The idea of space colonization has an almost poetic quality: Space is the next great frontier, the next great leap for humankind, that we hope to eventually conquer through our force of will and our ingenuity. From a more prosaic point of view, space colonization is important because it represents a long-term survival strategy for humankind1. -

The UK's Wealth Distribution and Characteristics of High

BRIEFING The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high- wealth households Arun Advani, George Bangham & Jack Leslie December 2020 resolutionfoundation.org @resfoundation The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households | 2 Acknowledgements This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the CAGE at Warwick (ES/L011719/1) and a COVID-19 Rapid Response Grant (ES/V012657/1), by LSE International Inequalities Institute AFSEE COVID-19 fund, and by the Standard Life Foundation. The authors thank Hannah Tarrant and Helen Hughson for outstanding research assistance, and Emma Chamberlain, Carla Kidd, Salvatore Morelli, and Andy Summers for helpful comments. This work contains statistical data from ONS which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. All errors remain the author’s own. Download This document is available to download as a free PDF at: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/ Citation If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is: A Advani, G Bangham & J Leslie, The UK’s wealth distribution and characteristics of high-wealth households: Reports are fun, Resolution Foundation, December 2020 Permission to share This document is published under the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 England and Wales Licence. This allows anyone to download, reuse, reprint, distribute, and/or copy Resolution Foundation publications without written permission subject to the conditions set out in the Creative Commons Licence. -

The Sunday Times Rich List 2008 Top 150

The Sunday Times Rich List 2008 Top 150 Return here from 2pm on Tuesday, April 29 to see full interactive table of Britain’s richest 2,000 Rank 2007 Rank Name Worth Source of wealth 1 1 Lakshmi Mittal and family £27,700m Steel 2 2 Roman Abramovich £11,700m Oil 3 3 The Duke of Westminster £7,000m Property 4 4 Sri and Gopi Hinduja £6,200m Industry 5 Alisher Usmanov £5,726m Steel 6 Ernesto and Kirsty Bertarelli £5,650m Pharmaceuticals 7 6 Hans Rausing and family £5,400m Packaging 8 8 John Fredriksen £4,650m Shipping 9 7 Sir Philip and Lady Green £4,330m Retailing 10 9 David and Simon Reuben £4,300m Property 11 Leonard Blavatnik £3,974m Industry 12 12= Sean Quinn and family £3,730m Property 13 12= Charlene and Michel de Carvalho £3,630m Inheritance 14 15 Kirsten and Jorn Rausing £3,500m Inheritance 15 Sammy and Eyal Ofer £3,336m Shipping 16 19 Vladimir Kim £2,987m Mining 17 17 Earl Cadogan and family £2,930m Property 18 Nicky Oppenheimer £2,870m Diamonds 19 16 Joe Lewis £2,800m Foreign exchange 20 11 Sir Richard Branson £2,700m Transport 21= 5 David Khalili £2,500m Art 21= Lev Leviev £2,500m Property 23 42 Anil Agarwal £2,450m Mining 24 20 Bernie and Slavica Ecclestone £2,400m Motor racing 25 10 Jim Ratcliffe £2,300m Chemicals 26 21 Mahdi al-Tajir £2,200m Metals 27 18 Nadhmi Auchi £2,150m Finance 28 51= Alan Parker £2,086m Duty-free shopping 29 23 Thor Bjorgolfsson £2,070m Pharmaceuticals 30 Mikhail Gutseriyev £2,015m Industry 31= 36= Laurence Graff £2,000m Diamonds 31= 14 Simon Halabi £2,000m Property 31= 24 Poju Zabludowicz £2,000m Property -

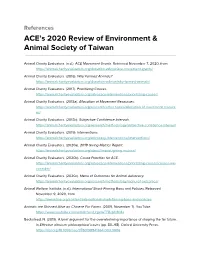

References: ACE's 2020 Review Of

References ACE’s 2020 Review of Environment & Animal Society of Taiwan Animal Charity Evaluators. (n.d.). ACE Movement Grants. Retrieved November 7, 2020, from https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/ace-movement-grants/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2016). Why Farmed Animals? https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/why-farmed-animals/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2017). Prioritizing Causes. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/advocacy-interventions/prioritizing-causes/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2018a). Allocation of Movement Resources. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/other-topics/allocation-of-movement-resourc es/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2018b). Subjective Confidence Intervals. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/methodology/subjective-confidence-interval/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2019). Interventions. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/advocacy-interventions/interventions/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2020a). 2019 Giving Metrics Report. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/about/impact/giving-metrics/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2020b). Cause Priorities for ACE. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/advocacy-interventions/prioritizing-causes/causes-we- consider/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2020c). Menu of Outcomes for Animal Advocacy. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/methodology/menu-of-outcomes/ Animal Welfare Institute. (n.d.). International Shark Finning Bans and Policies. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://awionline.org/content/international-shark-finning-bans-and-policies