Wealth Segmentation and the Mobilities of the Super-Rich: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

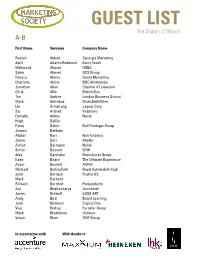

GUEST LIST the Shard | 12 March A-B

GUEST LIST The Shard | 12 March A-B First Name Surname Company Name Russell Abbott Synergis Marketing April Adams-Redmond Kerry Foods Mahmood Ahmed HSBC Salim Ahmed GCS Group Rebeca Alamo Quant Marketing Charlotte Aldiss BBC Worldwide Jonathan Allan Channel 4 Television Chris Allin British Gas Tim Ambler London Business School Mark Antrobus GlaxoSmithKline Ian Armstrong Jaguar Cars Saj Arshad Vodafone Danielle Atkins Nokia Hugh Baillie Patsy Baker Bell Pottinger Group Joanna Baldwin Alistair Barr Barr Gazetas Jayne Barr Abellio Adrian Barragan Nokia Simon Bassett EMR Alex Batchelor BrainJuicer Group Katie Beard The Ultimate Experience Adam Beckett AVIVA Michael Bedingfield Royal Automobile Club John Bernard Firefox OS Mark Bernard Richard Bernholt Periproducts Joy Bhattacharya Accenture James Bidwell CASS ART Andy Bird Brand Learning John Birkbeck Capital One Viya Bishay Eurostar Group Mark Bleathman Unilever Vivian Blom TMF Group In association with With thanks to GUEST LIST The Shard | 12 March B-C First Name Surname Company Name Chris Bowry Eurostar Group Emma Bradley BBC Nick Bradley City & Guilds Colin Bradshaw Rapp Russell Braterman Vodafone Francesca Brosan Omobono Lorna Brown John Lewis Lucas Brown Total Media Group Pamela Brown British Gas Rob Bruce Whyte & Mackay Kevin Bryant E.ON UK Richard Burdett Horse & Country TV Matt Burgess Unilever Hugh Burkitt The Marketing Society Ivor Burns Camelot UK Lotteries Joanna Burton Crescent Communications Amanda Campbell Capital Shopping Centres David Campbell World Brands Limited Dominic -

Underclass, Overclass, Ruling Class, Supernova Class1

EIGHT Underclass, overclass, ruling class, supernova class1 Danny Dorling Introduction One man in his mid-thirties hoped that his six-figure income would grow rapidly, and admitted that his assets would be valued at nearly a million pounds. He held strong views about poverty. “There is no poverty. Now you can get money from the state. People don’t even have to go to work. You don’t have to put up with working in an unrewarding situation.” He strongly disagreed with the propositions that the gap between rich and poor was too wide and that the rich should be more highly taxed. He strongly opposed the idea of putting limits on “some people’s expensive way of living” to reduce poverty and disagreed with the statement that a lot of people entitled to claim benefits do not claim them. Finally, he strongly agreed that cuts in public services like health and education could be made without increasing the number of people in poverty and that, if there was any poverty, it was more likely to be reduced by increasing Britain’s wealth than by making incomes more equal. (Peter Townsend, describing the views of one of the new overclass of London, recorded in 1985-86; see Townsend, 1993, p 109) By 2010 one in ten of all Londoners had the wealth of the man who Peter had described some 25 years earlier as being part of a tiny elite 155 fighting poverty, inequality and social injustice (see Hills et al, 2010). The Hills inquiry into inequality revealed that one in ten Londoners now have wealth of nearly a million pounds, some 273 times the wealth of the poorest tenth of today’s Londoners. -

“Affluenza” by Mark Harmon

Arab Youth, TV Viewing & “Affluenza” By Mark Harmon September, 2008. Popularized by several books, articles, and even a stage play over the last several years, a hypothesis known as “affluenza” predicts that media consumption will correlate positively with higher levels of materialistic traits. This paper re-analyzes data from a lifestyle survey administered to youth in Egypt and Saudi Arabia with an eye towards testing the affluenza hypothesis in light of the ongoing boom in Arab satellite television. While the survey was not specifically designed to test for affluenza, and therefore not an optimal tool, it did collect data on television viewing and several lifestyle topics which have been linked to affluenza in previous studies. Surprisingly, the data from this survey of Egyptian and Saudi youth did not show a link between increased television viewing and materialistic traits – in stark contrast to surveys conducted in the United States and Europe. Before 1990, when most Arabic television stations were state-controlled monopolies with limited transnational reach, it would not make much sense to consider Arab television in terms of materialism. Programs, delivered by land-based transmitters, generally followed the political line of the state, rarely delivering programming that could be called daring. As Abdallah Schleifer put it, “Arab television, which came into being during the high tide of republican police states, did not even attempt journalism. Its photographers covered only occasions of state, and there were no correspondents, since it was ‘information’ not news that was sought. Anchors could do the job of reading state news agency wire copy describing these ceremonial occasions while unedited footage was transmitted.”i Advertising existed, but was restricted heavily, and clustered between programs—not interrupting them.ii Free to air satellite TV networks, however, soon changed the media landscape. -

FIPP Management Board As at 21 March 2019 Chairman Ralph Büchi

FIPP Management Board as at 21 March 2019 Chairman Ralph Büchi, Chief Operating Officer of the Ringier Group & CEO of Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Switzerland Treasurer Erwin Fidelis Reisch, President & CEO, Alfons W. Gentner Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Germany President & CEO, James Hewes, President & CEO, FIPP - the network for global media, UK Directors Kaisa Ala-Laurila, CEO, A-lehdet Oy, Finland Srinivasan Balasubramanian, Managing Director, Ananda Vikatan Publishers Private Limited, India Natasha Christie-Miller, Divisional CEO, Ascential, Ascential, UK Enrique Micheli, Executive Director, Asociación Argentina de Editores de Revistas (AAER), Argentina Yolanda Ausín Castañeda, General Manager, Asociación de Revistas de Información (ARI), Spain Julia Raphaely, CEO, Associated Media Publishing, South Africa Jan Bayer, Member of the Executive Board & President News Media, Axel Springer SE, Germany Andrew Moultrie, Director of Consumer Products, Publishing and Web Properties, UK, BBC Studios Distribution Limited, UK Helen O'Donnell, Head of Development, TalentWorks, BBC Studios Distribution Limited, UK Alfred Heintze, COO, Burda International Holding GmbH, Germany Wu Shangzhi, President, China Periodicals Association (CPA), China Pierre Lamunière, President & Chairman, Edipresse Group, Switzerland Porfirio Sánchez Galindo, CEO, Editorial Televisa S.A. de C.V., Mexico Aaron Asadi, Chief Operations Officer, Future Publishing Ltd, UK Rolf Heinz, President & CEO Prisma Media, President G+J International -

Eight Reasons to Question Professor Cristobal Young's Conclusions

Eight Reasons to Question Professor Cristobal Young’s Conclusions about Millionaire Migration By Greg Sullivan WHITE PAPER No. 182 | May 2018 PIONEER INSTITUTE Pioneer’s Mission Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government. This paper is a publication of Pioneer Oppor- Pioneer Education seeks to increase the edu- tunity, which seeks to keep Massachusetts com- cation options available to parents and students, petitive by promoting a healthy business climate, drive system-wide reform, and ensure account- transparent regulation, small business creation in ability in public education. The Center’s work urban areas and sound environmental and devel- builds on Pioneer’s legacy as a recognized leader opment policy. Current initiatives promote mar- in the charter public school movement, and as ket reforms to increase the supply of affordable a champion of greater academic rigor in Mas- housing, reduce the cost of doing business, and sachusetts’ elementary and secondary schools. revitalize urban areas. Current initiatives promote choice and compe- tition, school-based management, and enhanced academic performance in public schools. Pioneer Health seeks to refocus the Massachu- Pioneer Public seeks limited, accountable gov- setts conversation about health care costs away ernment by promoting competitive delivery of from government-imposed interventions, toward public services, elimination of unnecessary reg- market-based reforms. Current initiatives include ulation, and a focus on core government func- driving public discourse on Medicaid; present- tions. -

Warren Wealth Tax Would Have Raised $114 Billion in 2020 from Nation’S 650 Billionaires Alone

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MARCH 1, 2021 WARREN WEALTH TAX WOULD HAVE RAISED $114 BILLION IN 2020 FROM NATION’S 650 BILLIONAIRES ALONE Ten-Year Revenue Total Would Be $1.4 Trillion Even as Billionaire Wealth Continued to Grow WASHINGTON, D.C. – America’s billionaires would owe a total of about $114 billion in wealth tax for 2020 if the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act introduced today by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA) had been in effect last year, based on Forbes billionaire wealth data analyzed by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF) and the Institute for Policy Studies Project on Inequality (IPS). The ten-year revenue total would be about $1.4 trillion, and yet U.S. billionaire wealth would continue to grow. (The 10-year revenue estimate is explained below.) Billionaire wealth is top-heavy, so just the richest 15 own one-third of all the wealth and would thus be liable for about a third of the wealth tax (see table below). Under the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act, those 15 richest billionaires would have paid a total of $40 billion in wealth tax for the 2020 tax year, but their projected collective wealth would have still increased by more than half (53%), only slightly lower than their actual 58% increase in wealth without the wealth tax, since March 18, 2020, the rough beginning of the pandemic and the start date for this analysis. Full billionaire data is here. Some examples from the top of the list: Jeff Bezos would pay $5.7 billion in wealth taxes for 2020, lowering the size of his fortune from $191.2 billion to $185.5 billion, or 5%, but it still would have increased by two-thirds from March 18 to the end of the year. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 1907301 11/01/2010 Address for Service in India/Attorney Address

Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 1907301 11/01/2010 VINOD KHODARIA 144 A, IIND FLOOR, KATRA MASHROO, DARIBA KALAN, DELHI - 110006 SERVICES & CONSULTANCY PROVIDER INDIAN Address for service in India/Attorney address: BALAJI IP PRACTICE E-617 STREET NO- 11&12 WEST VINOD NAGAR I.P. EXTN. NEW DELHI-110092 Used Since :01/01/2010 DELHI ADVERTISING. BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE FUNCTIONS 4113 Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 2080096 04/01/2011 SMT. INDERJEET KAUR 532 - D - I, MERCHANT CHAMBER BUILDING, SADAR BAZAR, AGRA CANTT. AGRA, U.P SERVICES Address for service in India/Agents address: P. K. ARORA TAJ TRADE MARKS PVT. LTD, 110 ANAND VRINDAVAN SANJAY PLACE AGRA(U.P) Used Since :01/01/1990 DELHI ADVERTISING, MARKETING, BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICIAL FUNCTIONS & FRANCHISE DISTRIBUTION RELATING TO EDUCATION, PROVIDING OF TRAINING DANCE & MUSLCAI CLASSES, ENTERTAINMENT; SPORTING AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES INCLUDING ORGANIZING AND PRESENTING CONCERTS, FESTIVALS, MUSICAL PROGRAMMES INCLUDING GIDDHA, BHANGRA, PUNJABI CULTURAL PROGRAMME, WESTERN MUSIC, LIVE SHOWS, LIVE PERFORMANCES, D.J. SYSTEM, BAND, ORCHESTRA, SOUND SYSTEM, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND VOCALS, MUSIC AND LIGHT ARRANGEMENT, ARTISTIC EVENTS & ALL KIND OF EVENT ARRANGEMENTS, BEING INCLUDED IN CLASS - 35. THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER.. 4114 Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 2128607 11/04/2011 NAMITA NAYYAR trading as ;WOMEN FITNESS E-25, NEW AGRA -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 14 December 2017) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £760 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

Plutocracy: the Marketising of ‘Equality’ Within Neoliberalism

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Littler, J. (2013). Meritocracy as plutocracy: the marketising of ‘equality’ within neoliberalism. New Formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 80-81, pp. 52-72. doi: 10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/4167/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MERITOCRACY AS PLUTOCRACY: THE MARKETISING OF ‘EQUALITY’ UNDER NEOLIBERALISM Jo Littler Abstract Meritocracy, in contemporary parlance, refers to the idea that whatever our social position at birth, society ought to facilitate the means for ‘talent’ to ‘rise to the top’. This article argues that the ideology of ‘meritocracy’ has become a key means through which plutocracy is endorsed by stealth within contemporary neoliberal culture. -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

Income Mobility and the Persistence of Millionaires, 1999 to 2007

SPECIAL June 2010 No. 180 REPORT Income Mobility and the Persistence Of Millionaires, 1999 to 2007 By households move up from the bottom income Robert Carroll Summary Senior Fellow Concern over the rising gap between the rich quintile within ten years. Roughly 50 percent Tax Foundation and poor has been the primary rationale for also move down from the top quintile within ten President Obama’s redistributive policies. But years. one important aspect of the American economy that should lessen concerns about snapshots of This report generally confirms this same income inequality is the mobility of people up basic relationship using recent data covering the and down the economic ladder. nine years from 1999 through 2007: If people move quickly up and down • Nearly 60 percent of taxpayers move up through the income spectrum, the position they from the bottom quintile within this nine- occupy at any point in time may be less of a year period. concern. Moreover, it is natural that people at different stages in their life cycle of earnings— • Nearly 40 percent of taxpayers move down just entering the work force, just retired, or from the top quintile within this nine-year midlife during their peak earnings years—would period. occupy different rungs of the economic ladder. • Nearly 60 percent of taxpayers are in a dif- Research has documented that our economy ferent quintile in 2007 than they were in exhibits considerable mobility. Roughly half of 1999. Key Findings • Concerns over increased income inequality should be tempered by the fact that a substantial number of households move up or down through the income distribution over time. -

Top Wealth Shares in the UK Over More Than a Century*

TOP WEALTH SHARES IN THE UK OVER MORE THAN A CEN TURY Facundo Alvaredo Anthony B Atkinson Salvatore Morelli INET Oxford WorkinG Paper no. 2017-01 19 December 2016 Employment, Equity & Growth Programme Top wealth shares in the UK over more than a century* Facundo Alvaredo Paris School of Economics, INET at the Oxford Martin School and Conicet Anthony B Atkinson Nuffield College, London School of Economics, and INET at the Oxford Martin School Salvatore Morelli CSEF – University of Naples “Federico II” and INET at the Oxford Martin School This version: 19 December 2016 Abstract Recent research highlighted controversy about the evolution of concentration of personal wealth. In this paper we provide new evidence about the long-run evolution of top wealth shares for the United Kingdom. The new series covers a long period – from 1895 to the present – and has a different point of departure from the previous literature: the distribution of estates left at death. We find that the application to the estate data of mortality multipliers to yield estimates of wealth among the living does not substantially change the degree of concentration over much of the period both, in the UK and US, allowing inferences to be made for years when this method cannot be applied. The results show that wealth concentration in the UK remained relatively constant during the first wave of globalization, but then decreased dramatically in the period from 1914 to 1979. The UK went from being more unequal in terms of wealth than the US to being less unequal. However, the decline in UK wealth concentration came to an end around 1980, and since then there is evidence of an increase in top shares, notably in the distribution of wealth excluding housing in recent years.