Minimal Conditions for Painting by Neil Haddon BA (Hons)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION from PICTURES to OBJECTS Monica Amor

REVIEW ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/3/2/101/720214/artm_r_00083.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION FROM PICTURES TO OBJECTS monica amor suárez, osbel. cold america: geometric abstraction in latin america (1934–1973). exhibition presented by the Fundación Juan march, madrid, Feb 11–may 15, 2011. crispiani, alejandro. Objetos para transformar el mundo: Trayectorias del arte concreto-invención, Argentina y Chile, 1940–1970 [Objects to Transform the World: Trajectories of Concrete-Invention Art, Argentina and Chile, 1940–1970]. buenos aires: universidad nacional de Quilmes, 2011. The literature on what is generally called Latin American Geometric Abstraction has grown so rapidly in the past few years, there is no doubt that the moment calls for some refl ection. The fi eld has been enriched by publications devoted to Geometric Abstraction in Uruguay (mainly on Joaquín Torres García and his School of the South), Argentina (Concrete Invention Association of Art and Madí), Brazil (Concretism and Neoconcretism), and Venezuela (Geometric Abstraction and Kinetic Art). The bulk of the writing on these movements, and on a cadre of well-established artists, has been published in exhibition catalogs and not in academic monographs, marking the coincidence of this trend with the consolidation of major private collections and the steady increase in auction house prices. Indeed, exhibitions of what we can broadly term Latin American © 2014 ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute -

Room to Rise: the Lasting Impact of Intensive Teen Programs in Art Museums

ROOM the lasting impact of intensive teen programs in art museums to rise Room to Rise: The Lasting Impact of Intensive Teen Programs in Art Museums Danielle Linzer and Mary Ellen Munley Editor: Ellen Hirzy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Copyright © 2015 by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Whitney Museum of American Art 99 Gansevoort Street New York, NY 10014 whitney.org Generous funding for this publication has been provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Project Director Danielle Linzer Lead Researcher Mary Ellen Munley Editor Ellen Hirzy Copyeditor Thea Hetzner Designers Hilary Greenbaum and Virginia Chow, Graphic Design Department, Whitney Museum of American Art ISBN: 978–0–87427–159–1 Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. Printed and bound by Lulu.com Front cover: Youth Insights, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (top); Teen Council, Museum of Contemporary Arts Houston (bottom) Back cover: Walker Art Center Teen Arts Council, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (top); MOCA and Louis Vuitton Young Arts Program, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (bottom) PREFACE 6 INTRODUCTION 8 1: DESIGNING 16 THE STUDY 2: CHANGING LIVES 22 3: CHANGING 58 MUSEUMS 4: SHAPING OUR 64 PRACTICE PROGRAM PROFILES 76 NOTES 86 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 90 Room to Rise: The Lasting Impact of Intensive 4 Teen Programs in Art Museums PREFACE ADAM D. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Download Press Release Here

! For Immediate Release 1 May 2019 Artists Announced for New Contemporaries 70th Anniversary Constantly evolving and developing along with the changing face of visual art in the UK, to mark its 70th anniversary, New Contemporaries is pleased to announce this year's selected artists with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. The panel of guest selectors comprising Rana Begum, Sonia Boyce and Ben Rivers has chosen 45 artists for the annual open submission exhibition. Since 1949 New Contemporaries has played a vital part in the story of contemporary British art. Throughout the exhibition's history, a wealth of established artists have participated in New Contemporaries exhibitions including post-war figures Frank Auerbach and Paula Rego; pop artists Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney; YBAs Damien Hirst and Gillian Wearing; alongside contemporary figures such as Tacita Dean, Mark Lecky, Mona Hatoum, Mike Nelson and Chris Ofili; whilst more recently a new generation of artists including Ed Atkins, Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Rachel Maclean and Laure Prouvost have also taken part. Selected artists for Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2019 are: Jan Agha, Eleonora Agostini, Justin Apperley, Ismay Bright, Roland Carline, Liam Ashley Clark, Becca May Collins, Rafael Pérez Evans, Katharina Fitz, Samuel Fordham, Chris Gilvan- Cartwright, Gabriela Giroletti, Roei Greenberg, Elena Helfrecht, Mary Herbert, Laura Hindmarsh, Cyrus Hung, Yulia Iosilzon, Umi Ishihara, Alexei Alexander Izmaylov, Paul Jex, Eliot Lord, Annie Mackinnon, Renie Masters, Simone Mudde, Isobel Napier, Louis Blue Newby, Louiza Ntourou, Ryan Orme, Marijn Ottenhof, Jonas Pequeno, Emma Prempeh, Zoe Radford, Taylor Jack Smith, George Stamenov, Emily Stollery, Wilma Stone, Jack Sutherland, Xiuching Tsay, Alaena Turner, Klara Vith, Ben Walker, Ben Yau, Camille Yvert and Stefania Zocco. -

Fundraiser Catalogue As a Pdf Click Here

RE- Auction Catalogue Published by the Contemporary Art Society Tuesday 11 March 2014 Tobacco Dock, 50 Porters Walk Pennington Street E1W 2SF Previewed on 5 March 2014 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London The Contemporary Art Society is a national charity that encourages an appreciation and understanding of contemporary art in the UK. With the help of our members and supporters we raise funds to purchase works by new artists Contents which we give to museums and public galleries where they are enjoyed by a national audience; we broker significant and rare works of art by Committee List important artists of the twentieth century for Welcome public collections through our networks of Director’s Introduction patrons and private collectors; we establish relationships to commission artworks and promote contemporary art in public spaces; and we devise programmes of displays, artist Live Auction Lots Silent Auction Lots talks and educational events. Since 1910 we have donated over 8,000 works to museums and public Caroline Achaintre Laure Prouvost – Special Edition galleries – from Bacon, Freud, Hepworth and Alice Channer David Austen Moore in their day through to the influential Roger Hiorns Charles Avery artists of our own times – championing new talent, supporting curators, and encouraging Michael Landy Becky Beasley philanthropy and collecting in the UK. Daniel Silver Marcus Coates Caragh Thuring Claudia Comte All funds raised will benefit the charitable Catherine Yass Angela de la Cruz mission of the Contemporary Art Society to -

Abstraction in 1936: Barr's Diagrams

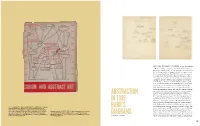

ALMOST SINCE THE MOMENT OF ITS FOUNDING, in 1929, The Museum of Modern Art has been committed to the idea that abstraction was an inherent and crucial part of the development of modern art. In fact the 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, organized by the Museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., made this argument its central thesis. In an attempt to map how abstraction came to be so important in modern art, Barr created a now famous diagram charting the history of Cubism’s and abstraction’s development from the 1890s to the 1930s, from the influence of Japanese prints to the aftermath of Cubism and Constructivism. Barr’s chart, which was published on the dust jacket of the exhibition’s catalogue (plate 452), began in an early version as a simple outline of the key factors affecting early modern art, and of the development of Cubism in particular, but over successive iterations became increasingly complex in its overlapping and intersecting lines of influence ABSTRACTION 1 (plates 453–58). The chart has two principal axes: on the vertical, time, and on the horizontal, styles or movements, with both lead- ing inexorably to the creation of abstract art. Key non-Western IN 1936: influences, such as “Japanese Prints,” “Near-Eastern Art,” and “Negro Sculpture,” are indicated by a red box. “Machine Esthetic” is also highlighted by a red box, and “Modern Architecture,” by 452. The catalogue for Cubism and Abstract Art, an exhibition at the Museum BARR’S which Barr meant the International Style, by a black box. -

Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms

ABSTRACT ART AND THE CONTESTED GROUND OF AFRICAN MODERNISMS By PATRICK MUMBA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of FINE ART of RHODES UNIVERSITY November 2015 Supervisor: Tanya Poole Co-Supervisor: Prof. Ruth Simbao ABSTRACT This submission for a Masters of Fine Art consists of a thesis titled Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms developed as a document to support the exhibition Time in Between. The exhibition addresses the fact that nothing is permanent in life, and uses abstract paintings that reveal in-between time through an engagement with the processes of ageing and decaying. Life is always a temporary situation, an idea which I develop as Time in Between, the beginning and the ending, the young and the aged, the new and the old. In my painting practice I break down these dichotomies, questioning how abstractions engage with the relative notion of time and how this links to the processes of ageing and decaying in life. I relate this ageing process to the aesthetic process of moving from representational art to semi-abstract art, and to complete abstraction, when the object or material reaches a wholly unrecognisable stage. My practice is concerned not only with the aesthetics of these paintings but also, more importantly, with translating each specific theme into the formal qualities of abstraction. In my thesis I analyse abstraction in relation to ‘African Modernisms’ and critique the notion that African abstraction is not ‘African’ but a mere copy of Western Modernism. In response to this notion, I have used a study of abstraction to interrogate notions of so-called ‘African-ness’ or ‘Zambian-ness’, whilst simultaneously challenging the Western stereotypical view of African modern art.