The Conservation Laundering of Illicit Antiquities

Total Page:16

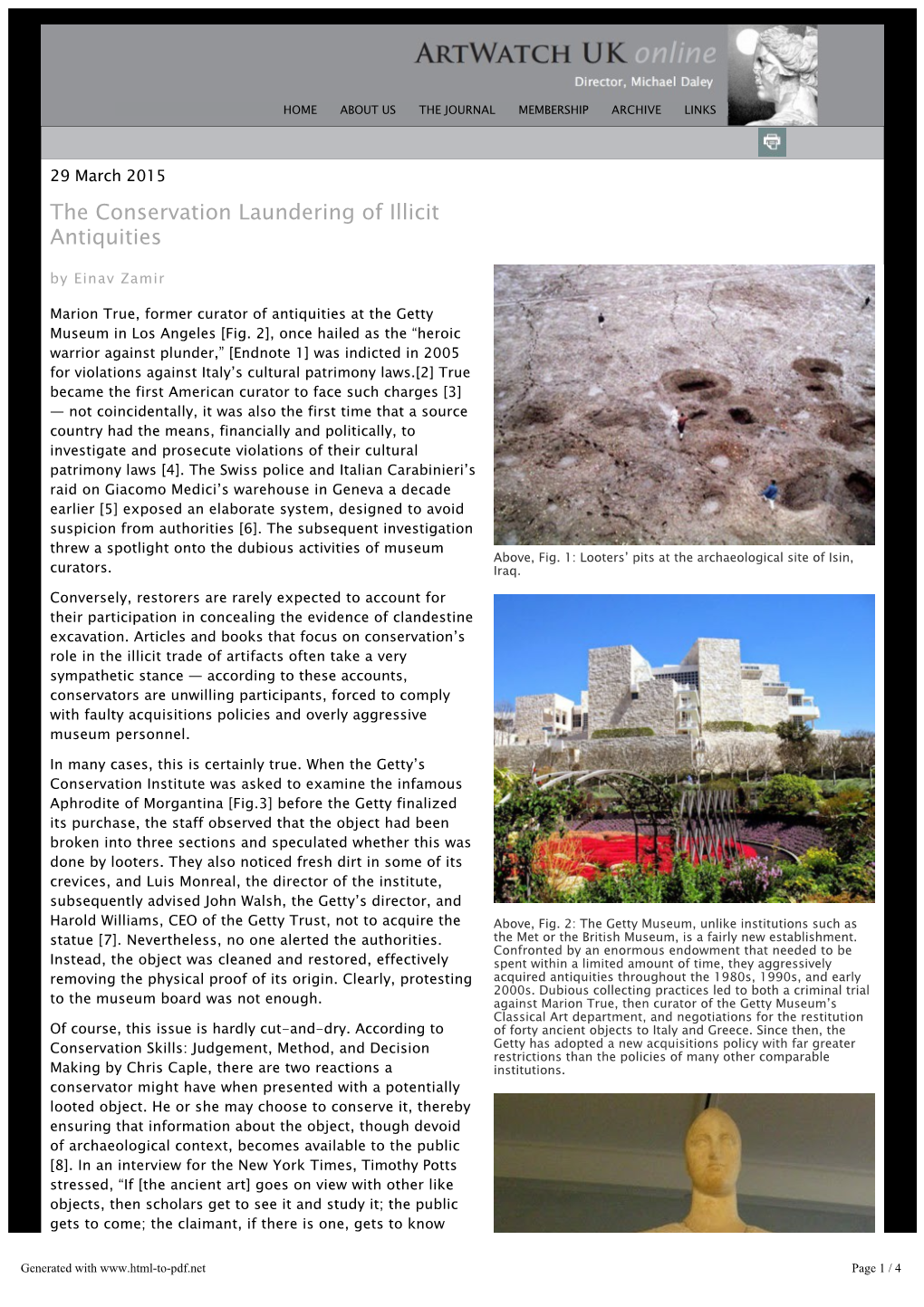

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Priceless Artifacts Return to Italy and Greece, but Their Histories Remain

ntiquities dealers Robert Hecht and Giacomo Medici should have tidied up their desks. Raids by the Italian police in 1995 and 2000 yielded a mountain Aof evidence—from photos of Greek and Roman artifacts still in the ground to Hecht’s handwritten memoir—that showed exactly how A Tangled Journey Home the two had been trafficking looted antiquities through the international art market for decades Priceless artifacts return to Italy (“Raiding the Tomb Raiders,” July/August and greece, but their histories 2006). Their clients included, among others, three preeminent American cultural institutions: remain lost. the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the J. Paul by Eti Bonn-Muller and Eric A. Powell Getty Museum, Malibu. Italy and Greece were simultaneously outraged and delighted with the news. Their long-standing suspicions were confirmed: Metropolitan MuSeuM of art artifacts recently acquired by major museums New York, New York had been looted from their soil. And they lthough the Met maintains that it acquired the jumped at the opportunity to get them back. artifacts in good faith, the museum has already trans- Years of negotiations in the style of a Greek Aferred title of 21 objects to Italy’s Ministry of Culture. So tragedy finally paid off and have resulted in some far, the Met has sent back four terracotta vessels and is planning delicately worded agreements providing for to return the other objects over the next few years. As part of the repatriations and reciprocal long-term loans. 2006 agreement, the Ministry is allowing the Met to display the The following pages showcase a handful of remaining pieces for a while longer to coincide with the opening of the 62 artifacts that have been (or are slated to the museum’s new Greek and Roman galleries. -

Empty International Museums' Trophy Cases of Their Looted Treasures

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 36 Number 1 Winter Article 5 April 2020 Empty International Museums' Trophy Cases of Their Looted Treasures and Return Stolen Property to the Countries of Origin and the Rightful Heirs of Those Wrongfully Dispossessed Michael J. Reppas II Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Michael J. Reppas, Empty International Museums' Trophy Cases of Their Looted Treasures and Return Stolen Property to the Countries of Origin and the Rightful Heirs of Those Wrongfully Dispossessed, 36 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 93 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. EMPTY "INTERNATIONAL" MUSEUMS' TROPHY CASES OF THEIR LOOTED TREASURES AND RETURN STOLEN PROPERTY TO THE COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN AND THE RIGHTFUL HEIRS OF THOSE WRONGFULLY DISPOSSESSED MICHAEL J. REPPAS II * The discovery of the earliestcivilizations [in the 19 th Century] was a glorious adventure story.... Kings visited digs in Greece and Egypt, banner headlines announced the latestfinds, and thousandsflocked to see exotic artifactsfrom distant millennia in London, Berlin, and Paris. These were the pioneer days of archaeology,when excavators.., used battering rams, bruteforce, and hundreds of workmen in a frenzied searchfor ancientcities and spectacular artifacts. From these excavations was born the science of archaeology. They also spawned a past.I terrible legacy - concerted efforts to loot and rob the The ethical questions surrounding the acquisition and retention of looted property by museums and art dealers were once a subject reserved for mock-trial competitions in undergraduate humanities and pre-law classes. -

Enforcement of Foreign Cultural Patrimony Laws in US Courts

South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business Volume 4 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall 2007 Enforcement of Foreign Cultural Patrimony Laws in U.S. Courts: Lessons for Museums from the Getty Trial and Cultural Partnership Agreements of 2006 Carrie Betts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Betts, aC rrie (2007) "Enforcement of Foreign Cultural Patrimony Laws in U.S. Courts: Lessons for Museums from the Getty Trial and Cultural Partnership Agreements of 2006," South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENFORCEMENT OF FOREIGN CULTURAL PATRIMONY LAWS IN U.S. COURTS: LESSONS FOR MUSEUMS FROM THE GETTY TRIAL AND CULTURAL PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS OF 2006 CarrieBetts* "Until now we have dreamed, we have slept. Now it is time to wake up." - Maurizio Fiorelli, Italian Prosecutor in the Getty trial.' I. INTRODUCTION Until the former curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Marion True, was indicted on criminal charges and hauled into the Tribunale Penale di Roma for trafficking in stolen antiquities and criminal associations, the modem international trade in looted antiquities barely registered on the radars of most major media outlets. In the wake of the ongoing trial of True in Rome, museums across the U.S. -

Wednesday, March 23, 2011 Getty Ships Aphrodite Back to Sicily

Wednesday, March 23, 2011 Getty ships Aphrodite back to Sicily * After a long dispute the museum acknowledges the statue's true origins. Home Edition, Calendar, Page D-1 Entertainment Desk 20 inches; 857 words By Jason Felch, The J. Paul Getty Museum's iconic statue of Aphrodite was quietly escorted back to Sicily by Italian police last week, ending a decades-long dispute over an object whose craftsmanship, importance and controversial origins have been likened to the Parthenon marbles in the British Museum. The 7-foot tall, 1,300-pound statue of limestone and marble was painstakingly taken off display at the Getty Villa and disassembled in December. Last week, it was locked in shipping crates with an Italian diplomatic seal and loaded aboard an Alitalia flight to Rome, where it arrived on Thursday. From there it traveled with an armed police escort by ship and truck to the small hilltop town of Aidone, Sicily, where it arrived Saturday to waiting crowds. It was just outside this town, in the ruins of the ancient Greek colony of Morgantina, that authorities say the cult goddess lay buried for centuries before it was illegally excavated and smuggled out of Italy. When the Getty bought the Aphrodite for $18 million in 1988, the statue's importance outweighed the signs of its illicit origins. "The proposed statue of Aphrodite would not only become the single greatest piece of ancient art in our collection; it would be the greatest piece of Classical sculpture in this country and any country outside of Greece and Great Britain," wrote former antiquities curator Marion True in proposing the acquisition. -

Wednesday January 03, 2007 a TIMES INVESTIGATION the Getty's

Wednesday January 03, 2007 A TIMES INVESTIGATION The Getty's troubled goddess * Evidence mounts that the centerpiece of its antiquities collection, acquired despite several warnings, was looted. Home Edition, Main News, Page A-1 Metro Desk 114 inches; 4413 words Type of Material: Infographic; Infobox (text included here); List By Ralph Frammolino and Jason Felch, Times Staff Writers Liberated from its shipping crates, the ancient statue drew a crowd of employees when it arrived in December 1987 at the J. Paul Getty Museum's antiquities conservation lab. The 7 1/2 -foot figure had a placid marble face and delicately carved limestone gown. It was thought to depict Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. Some who came to see it believed that the sculpture would become the greatest piece in the museum's antiquities collection. One man, however, saw trouble. Luis Monreal, director of the Getty Conservation Institute, saw signs that the object had been looted. There was dirt in the folds of the gown, and the torso had what appeared to be new fractures, suggesting that the statue had been recently unearthed and broken apart for easy smuggling. "Any museum professional looking at an archeological piece in those conditions had to suspect it came from an illicit origin," Monreal recalled in a recent interview. He said he warned the museum's director not to buy the statue and asked him to test the pollen in the dirt, which might indicate where the work had been found. The test was never done. Today, the 2,400-year-old Aphrodite, the best-known work in the Getty's antiquities collection, is at the center of a showdown with Italy over looted ancient artworks. -

Protecting Cultural Heritage by Strictly Scrutinizing Museum Acquisitions

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 24 Volume XXIV Number 3 Volume XXIV Book 3 Article 4 2014 Protecting Cultural Heritage by Strictly Scrutinizing Museum Acquisitions Leila Alexandra Amineddoleh Fordham University School of Law; St. John's University - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Leila Alexandra Amineddoleh, Protecting Cultural Heritage by Strictly Scrutinizing Museum Acquisitions, 24 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 729 (2015). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol24/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Cultural Heritage by Strictly Scrutinizing Museum Acquisitions Cover Page Footnote Leila Amineddoleh is an art and cultural heritage attorney, the Executive Director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation, and an adjunct professor at Fordham University School of Law. She would like to acknowledge Filippa Anzalone, Jane Pakenham, Kelvin Collado, and Amanda Rottermund for their valuable insights and assistance. This article is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol24/iss3/4 Protecting Cultural Heritage by Strictly Scrutinizing Museum Acquisitions Leila Amineddoleh* INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 731 I. BACKGROUND ............................................................... 735 A. Cultural Heritage Looting ..................................... -

Sunday June 18, 2006 the STATE Getty's List of Doubts Multiplies * a Museum Review Finds 350 Works Bought from Dealers Suspected

Sunday June 18, 2006 THE STATE Getty's List of Doubts Multiplies * A museum review finds 350 works bought from dealers suspected of trafficking in looted art. Italian authorities have not been given details. Home Edition, Main News, Page A-1 Metro Desk 27 inches; 953 words By Jason Felch And Ralph Frammolino, Times Staff Writers An internal review by the J. Paul Getty Trust has found that 350 Greek, Roman and Etruscan artifacts in its museum's prized antiquities collection were purchased from dealers identified by foreign authorities as being suspected or convicted of dealing in looted artifacts. The review, conducted last year to gauge the Getty's exposure to claims against objects in its collection, shows that the trust purchased far more pieces from suspect dealers than has been previously disclosed. The assessment valued the 350 vases, urns, statues and other sculptures at close to $100 million. That is in addition to 52 items in the Getty collection that Italy has demanded back, contending they were illegally excavated and exported. The assessment does not address the question of whether any of the 350 objects were purchased illegally, nor does it evaluate their artistic significance. But Getty records show that they include 35 of the museum's 104 masterpieces. The Getty has not provided Italian authorities with its review of the 350 pieces, a fact that could complicate talks set to resume Monday in Rome between the trust and representatives of Italy's Ministry of Culture over the 52 contested items. Maurizio Fiorilli, a state attorney and the lead negotiator for the ministry, expressed surprise late last week when told of the Getty's findings about the 350 objects. -

Museum Malpractice As Corporate Crime? the Case of the J. Paul Getty Museum Neil Brodiea and Blythe Bowman Proulxb*

Journal of Crime and Justice, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 3, 399–421, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2013.819785 Museum malpractice as corporate crime? The case of the J. Paul Getty Museum Neil Brodiea and Blythe Bowman Proulxb* aScottish Centre for Crime & Justice Research, School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; bCriminal Justice, L. Douglas Wilder School of Government & Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA (Received 19 March 2013; final version received 23 June 2013) Within a corporate criminological framework, this paper examines the antiquities acquisition policies and activities of the J. Paul Getty Museum particularly during the curatorship of Marion True, whose indictment by the Italian government was part of a broader investigation into the trade of illicitly obtained Italian antiquities. Specifically, we employ two theoretical perspectives – that of differential association and anomie – to examine malpractice among Getty officers and suggest that both museum cultures and the psychology of collecting may in fact be criminogenic. In light of such criminological insight, we conclude the paper with suggestions for broad reforms of museum governance. Keywords: corporate crime; antiquities; museum governance; collecting; anomie; differential association Introduction The US art museums’ community was shocked when on 16 November 2005, Marion True appeared before a criminal court in Rome, Italy, to face charges of receiving stolen antiquities, trafficking, and conspiracy to traffic (Lufkin 2005). From 30 April 1986 until 1 October 2005, True had been Curator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, which was, at the time, the wealthiest collecting institution in the United States with an endowment in the mid 1980s of several billion dollars (Felch and Frammolino 2011, 54). -

Sunday, May 29, 2011 CULTURAL EXCHANGE the Goddess Of

Sunday, May 29, 2011 CULTURAL EXCHANGE The goddess of mystery, perhaps * The Getty's former prized statue may be settled in Italy, but what's not settled is who exactly she represents. Home Edition, Sunday Calendar, Page E-2 Calendar Desk 22 inches; 877 words By Jason Felch, AIDONE, ITALY -- In ancient times, central Sicily was the bread basket of the Western world. Fields of rolling wheat and wildflowers, groves of olive and pomegranate and citrus -- even today, fertility seems to spring from the volcanic soils surrounding Mt. Etna as if by divine inspiration. It was here on the shores of Lake Pergusa that ancient sources say Persephone, the goddess of fertility, was abducted by Hades and taken to the underworld. She was forced to return there for three months every year, the Greek explanation for the barren months of winter. When Greek colonists settled the region some 2,500 years ago, they built cult sanctuaries to Persephone and her mother, Demeter. The ruins of Morgantina, the major Greek settlement built here, brim with terra-cotta and stone icons of the two deities. It seems a fitting new home for the J. Paul Getty Museum's famous cult statue of a goddess, which many experts now believe represents Persephone, not Aphrodite, as she has long been known. Since the Getty's controversial purchase of the statue in 1988 for $18 million, painstaking investigations by police, curators, academics, journalists, attorneys and private investigators have pieced together the statue's journey from an illicit excavation in Morgantina in the late 1970s to the Getty Museum. -

Morgantina Goddess”, a Classical Cult Statue from Sicily Between Old and New Mythology

Искусство и художественная культура Древнего мира 169 УДК: 7.032’02”-5/-4”(38); 7.061 ББК: 85.133(0)32 А43 DOI: 10.18688/aa177-1-18 Flavia Zisa Art without Context: The “Morgantina Goddess”, a Classical Cult Statue from Sicily between Old and New Mythology The so-called Morgantina Goddess (Ill. 29) represents an important case study for strategies and methodologies to be adopted on an ancient artifact resulting from illegal excavations, and thus deprived of its context, identity and history by the criminal network1. Formerly known as the “Getty Aphrodite”2, the classical statue, dated around 400 BC, was stolen by looters in Sicily, bought by the Getty Museum in 1987, and returned to the Italian State following an agreement signed in September 2007, and finally exhibited at the Museo Regionale di Aidone in May 20113. The statue is thought to have been excavated illegally from the ruins of the ca. 6th BC —1st AD town of Morgantina in Sicily (Fig. 1), where the US archae- ologists have been excavating since 19554. For a long time the sculpture has been the worldwide symbol of looted antiquities: scandals, millionaire checks, investigations, dealers, and also the public exposure of excellent archaeol- ogists and their unclear swinging between art and crime. A mix of elements has created a very popular new mythology surrounding the statue, which has made Italian words “Tombaroli” and “Clandestini” as famous as Spaghetti, Pizza and Cappuccino, so far in so to have been added — with good reason! — to the international Italian dictionary. 1 I wish to thank the VII Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art International Conference Commit- tee (2016) for their kind invitation to present this work that constitutes a preview of sorts of a future project. -

The Victorious Youth

THE VICTORIOUS YOUTH THE VICTORIOUS YOUTH Carol C. Mattusch GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES Christopher Hudson, Publisher Frontispiece: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Statue of a Victorious Youth [detail], probably third —second century B.C. Benedicte Gilman, Editor Bronze with copper inlays, Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator height 151.5 cm (59% in.) Pamela Patrusky Mass, Designer Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (yy.AB^o) Ellen Rosenbery, Jack Ross, Photographers David Fuller, Cartographer All works are reproduced (and photographs provided) © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise indicated. 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1000 Los Angeles, California 90049-1687 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas Library of Congress Printed in Hong Kong by Imago Cataloging-m-Publication Data Mattusch, Carol C. The victorious youth / Carol C. Mattusch p. cm. — (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN o-89236-47o-x i. Getty bronze (Statue) 2. Bronze sculpture, Greek — Expertising. 3. Bronze sculpture, Greek—Rome. 4. Bronze sculpture — Collectors and collecting — Rome. I. Title. II. Series. NBi4o.M39 1997 733'-3— dc2i 97-6758 CIP CONTENTS Map vi Introduction i Rescued from the Sea: Shipwrecks and Chance Finds 3 Statues for Civic Pride 23 Statues for Victors 36 Collectors in Antiquity 52 Collaborators: Artist and Craftsman 62 Modern Views of the Victorious Youth 78 Notes 92 Selected Bibliography 99 Appendix: Measurements 100 Acknowledgments 104 Final page folds out, providing a reference color plate of the statue of a Victorious Youth vi INTRODUCTION n the world of classical art and archaeology, the J. -

Antiquities Trafficking in Modern Times: How Italian Skullduggery Will Affect United States Museums

Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 2 2007 Antiquities Trafficking in Modern Times: How Italian Skullduggery Will Affect United States Museums Christine L. Green Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Christine L. Green, Antiquities Trafficking in Modern Times: How Italian Skullduggery Will Affect United States Museums, 14 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 35 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol14/iss1/2 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Green: Antiquities Trafficking in Modern Times: How Italian Skullduggery Comments ANTIQUITIES TRAFFICKING IN MODERN TIMES: HOW ITALIAN SKULLDUGGERY WILL AFFECT UNITED STATES MUSEUMS Archaeology is not a science; it's a vendetta.' INTRODUCTION A. The Old Story For as long as colonialism has thrived and wars fought, coun- tries have pillaged other civilizations' treasures and brought them home to demonstrate their nations' power and hegemony. 2 "No doubt, theft is at the root of many tides; and priceless archaeologi- cal artifacts obtained in violation of local law are to be found in reputable museums all over the world." 3 Because of centuries of tomb-robbers and raiders, numerous countries are lobbying foreign governments for the return of their national treasures. Greece, for example, requested the return of the Parthenon (Elgin) Marbles on display at the British Museum, Ethiopia sought the Obelisk of 1.