Morgantina Goddess”, a Classical Cult Statue from Sicily Between Old and New Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buccini the Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe

Anthony Buccini The Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe Pe-i boccoin boin se fan e questioin. Genoese proverb 1 Introduction In the past several decades it has become received opinion among food scholars that the Arabs played the central rôle in the diffusion of pasta as a common food in Europe and that this development forms part of their putative broad influence on culinary culture in the West during the Middle Ages. This Arab theory of the origins of pasta comes in two versions: the basic version asserts that, while fresh pasta was known in Italy independently of any Arab influence, the development of dried pasta made from durum wheat was a specifically Arab invention and that the main point of its diffusion was Muslim Sicily during the period of the island’s Arabo-Berber occupation which began in the 9th century and ended by stages with the Norman conquest and ‘Latinization’ of the island in the eleventh/twelfth century. The strong version of this theory, increasingly popular these days, goes further and, though conceding possible native European traditions, posits Arabic origins not only for dried pasta but also for the names and origins of virtually all forms of pasta attested in the Middle Ages, albeit without ever providing credible historical and linguistic evidence; Clifford Wright (1999: 618ff.) is the best known proponent of this approach. In AUTHOR 2013 I demonstrated that the commonly held belief that lasagne were an Arab contribution to Italy’s culinary arsenal is untenable and in particular that the Arabic etymology of the word itself, proposed by Rodinson and Vollenweider, is without merit: both word and item are clearly of Italian origin. -

Priceless Artifacts Return to Italy and Greece, but Their Histories Remain

ntiquities dealers Robert Hecht and Giacomo Medici should have tidied up their desks. Raids by the Italian police in 1995 and 2000 yielded a mountain Aof evidence—from photos of Greek and Roman artifacts still in the ground to Hecht’s handwritten memoir—that showed exactly how A Tangled Journey Home the two had been trafficking looted antiquities through the international art market for decades Priceless artifacts return to Italy (“Raiding the Tomb Raiders,” July/August and greece, but their histories 2006). Their clients included, among others, three preeminent American cultural institutions: remain lost. the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the J. Paul by Eti Bonn-Muller and Eric A. Powell Getty Museum, Malibu. Italy and Greece were simultaneously outraged and delighted with the news. Their long-standing suspicions were confirmed: Metropolitan MuSeuM of art artifacts recently acquired by major museums New York, New York had been looted from their soil. And they lthough the Met maintains that it acquired the jumped at the opportunity to get them back. artifacts in good faith, the museum has already trans- Years of negotiations in the style of a Greek Aferred title of 21 objects to Italy’s Ministry of Culture. So tragedy finally paid off and have resulted in some far, the Met has sent back four terracotta vessels and is planning delicately worded agreements providing for to return the other objects over the next few years. As part of the repatriations and reciprocal long-term loans. 2006 agreement, the Ministry is allowing the Met to display the The following pages showcase a handful of remaining pieces for a while longer to coincide with the opening of the 62 artifacts that have been (or are slated to the museum’s new Greek and Roman galleries. -

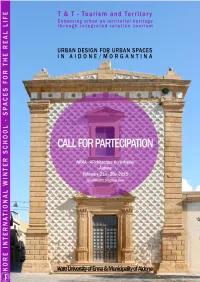

Call for Partecipation.Pdf

The Faculty of Engineering and Architecture at the ARKA Lab in Aidone offers the opportunity of a full- time research and didactic experience in enhancing urban & territorial heritage through Integrated Relational Tourism. An activity focused on the issue of Urban Design for Urban Spaces in Aidone/Morgantina as an opportunity aimed to improve the quality of life so as the local economic development for the communities of the inland rural areas. The Kore International Winter School 2015, represents a continuous of activities as interviews and meetings, workshops and expositions, lectures and site visits that, through 8 full days of common work, should explore problems and hopefully propose a range of visions for the future of the city and of the hinterland of Aidone-Morgantina and its heritage. The Kore International Winter School 2015 includes field trips and guided visits to the study site of Aidone and Morgantina, Piazza Armerina and Villa del Casale, Enna and Pergusa areas as well as social and cultural events. The School activities are articulated on three structural goals, which are: - the activity of scientific and applied Research, implicit in the proposed innovative approach as in the chosen application field; - the integrated project implementation Scenarios, as expected design results by the workshop; - the Training for new needed professionals, important to manage the transition to a different development model from the current one. Official and work languages Official language: English (for meetings, lectures, exibitions, etc.) Work languages: Arabic and Italian (for any other informal relationships!) Short Presentation The Winter School aims to promote a trans-disciplinary and international approach that encourages the development of skills and knowledge in the field of Integrated Tourism managed by the territory through its local actors and resources. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

Meredith College Travel Letter Sicily, Italy

Dear Friends of Meredith Travel, I just spent a most enjoyable morning. In preparation for writing this letter about our September 25-October 7, 2018, tour of Sicily, I reviewed my photographs from the trip I made there this past summer. I simply can’t wait to go back! Betty describes southern Italy as Italy to the 3rd power—older, grander, and more richly complex. Sicily, we agree, is Italy to the 10th power, at least. It was, by far, the most exotic version of our favorite country that I have yet to encounter, made so by its location and history, which includes a dizzying mix of cultures. It was Greek far longer than it has been Italian. It was Arab. Norman. Swabian. Aragonese. Austrian. Even Bourbon French! All left their mark. And finally, and relatively recently (1860), the Risorgimento fought it into being part of unified Italy. The food, the architecture, and customs can best be understood by experiencing them all firsthand, so without further ado, I would like to summarize our itinerary for you. Join me now as we vicariously tour Sicily together. Day 1: Sept. 25 (Tues) Departure. We depart the U.S. to arrive the next day in Palermo, the capital of the autonomous region of Sicily. Day 2: Sept. 26 (Wed) Palermo. Palermo is a city of 700,000, by far the largest on the island, with an ancient historic city center with structures representing the panorama of its past. After a quick driving tour to orient us to the city, we stop, drop bags at the hotel, and head out to see perhaps the most perfect medieval buildings in the world, the Norman Palace and Palatine Chapel, the latter known for its extraordinary mosaics designed in such a way that the aesthetics of the Arab, Jewish, and Norman artisans are all incorporated. -

Empty International Museums' Trophy Cases of Their Looted Treasures

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 36 Number 1 Winter Article 5 April 2020 Empty International Museums' Trophy Cases of Their Looted Treasures and Return Stolen Property to the Countries of Origin and the Rightful Heirs of Those Wrongfully Dispossessed Michael J. Reppas II Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Michael J. Reppas, Empty International Museums' Trophy Cases of Their Looted Treasures and Return Stolen Property to the Countries of Origin and the Rightful Heirs of Those Wrongfully Dispossessed, 36 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 93 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. EMPTY "INTERNATIONAL" MUSEUMS' TROPHY CASES OF THEIR LOOTED TREASURES AND RETURN STOLEN PROPERTY TO THE COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN AND THE RIGHTFUL HEIRS OF THOSE WRONGFULLY DISPOSSESSED MICHAEL J. REPPAS II * The discovery of the earliestcivilizations [in the 19 th Century] was a glorious adventure story.... Kings visited digs in Greece and Egypt, banner headlines announced the latestfinds, and thousandsflocked to see exotic artifactsfrom distant millennia in London, Berlin, and Paris. These were the pioneer days of archaeology,when excavators.., used battering rams, bruteforce, and hundreds of workmen in a frenzied searchfor ancientcities and spectacular artifacts. From these excavations was born the science of archaeology. They also spawned a past.I terrible legacy - concerted efforts to loot and rob the The ethical questions surrounding the acquisition and retention of looted property by museums and art dealers were once a subject reserved for mock-trial competitions in undergraduate humanities and pre-law classes. -

A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily Davide Provenzano Master Programme in System Dynamics Department of Geography University of Bergen Spring 2009 Acknowledgments I am grateful to the Statistical Office of the European Communities (EUROSTAT); the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); the European Climate Assessment & Dataset (ECA&D 2009), the Statistical Office of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Craft Trade and Agriculture (CCIAA) of Palermo; the Italian Automobile Club (A.C.I), the Italian Ministry of the Environment, Territory and Sea (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare), the Institute for the Environmental Research and Conservation (ISPRA), the Regional Agency for the Environment Conservation (ARPA), the Region of Sicily and in particular to the Department of the Environment and Territory (Assessorato Territorio ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente - servizio 6), the Department of Arts and Education (Assessorato Beni Culturali, Ambientali e P.I. – Dipartimento Beni Culturali, Ambientali ed E.P.), the Department of Communication and Transportation (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento dei Trasporti e delle Comunicazioni), the Department of Tourism, Sport and Culture (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento Turismo, Sport e Spettacolo), for the high-quality statistical information service they provide through their web pages or upon request. I would like to thank my friends, Antonella (Nelly) Puglia in EUROSTAT and Antonino Genovesi in Assessorato Turismo ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente – servizio 6, for their direct contribution in my activity of data collecting. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Quod Omnium Nationum Exterarum Princeps Sicilia

Quod omnium nationum exterarum princeps Sicilia A reappraisal of the socio-economic history of Sicily under the Roman Republic, 241-44 B.C. Master’s thesis Tom Grijspaardt 4012658 RMA Ancient, Medieval and Renaissance Studies Track: Ancient Studies Utrecht University Thesis presented: June 20th 2017 Supervisor: prof. dr. L.V. Rutgers Second reader: dr. R. Strootman Contents Introduction 4 Aims and Motivation 4 Structure 6 Chapter I: Establishing a methodological and interpretative framework 7 I.1. Historiography, problems and critical analysis 7 I.1a.The study of ancient economies 7 I.1b. The study of Republican Sicily 17 I.1c. Recent developments 19 I.2. Methodological framework 22 I.2a. Balance of the sources 22 I.2b. Re-embedding the economy 24 I.3. Interpretative framework 26 I.3a. Food and ideology 27 I.3b. Mechanisms of non-market exchange 29 I.3c. The plurality of ancient economies 32 I.4. Conclusion 38 Chapter II. Archaeology of the Economy 40 II.1. Preliminaries 40 II.1a. On survey archaeology 40 II.1b. Selection of case-studies 41 II.2. The Carthaginian West 43 II.2a. Segesta 43 II.2b. Iatas 45 II.2c. Heraclea Minoa 47 II.2d. Lilybaeum 50 II.3. The Greek East 53 II.3a. Centuripe 53 II.3b. Tyndaris 56 II.3c. Morgantina 60 II.3d. Halasea 61 II.4. Agriculture 64 II.4a. Climate and agricultural stability 64 II.4b. On crops and yields 67 II.4c. On productivity and animals 70 II.5. Non-agricultural production and commerce 72 II.6. Conclusion 74 Chapter III. -

Contrada Agnese Project (CAP)

The Journal of Fasti Online (ISSN 1828-3179) ● Published by the Associazione Internazionale di Archeologia Classica ● Palazzo Altemps, Via Sant’Appolinare 8 – 00186 Roma ● Tel. / Fax: ++39.06.67.98.798 ● http://www.aiac.org; http://www.fastionline.org Preliminary Report on the 2018 Season of the American Excavations at Morgantina: Contrada Agnese Project (CAP) Christy Schirmer – D. Alex Walthall – Andrew Tharler – Elizabeth Wueste – Benjamin Crowther – Randall Souza – Jared Benton – Jane Millar In its sixth season, the American Excavations at Morgantina: Contrada Agnese Project (CAP) continued archaeological investigations inside the House of the Two Mills, a modestly-appointed house of Hellenistic date located near the west- ern edge of the ancient city of Morgantina. This report gives a phase-by-phase summary of the significant discoveries from the 2018 excavation season, highlighting the architectural development of the building as well as evidence for the various activities that took place there over the course of its occupation. Introduction The sixth season of the American Excavations at Morgantina: Contrada Agnese Project (CAP) took place between 25 June and 27 July 20181. Since 2014, the focus of the CAP excavations has been the House of the 1 Our work was carried out under the auspices of the American Excavations at Morgantina (AEM) and in cooperation with authori- ties from the Soprintendenza per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali and Parco Archeologico Regionale di Morgantina. We would like to thank Prof. Malcolm Bell III and Prof. Carla Antonaccio, Directors of the American Excavations at Morgantina, for their permission and constant encouragement as we pursue this project. -

Ancient Greek Architecture

Greek Art in Sicily Greek ancient temples in Sicily Temple plans Doric order 1. Tympanum, 2. Acroterium, 3. Sima 4. Cornice 5. Mutules 7. Freize 8. Triglyph 9. Metope 10. Regula 11. Gutta 12. Taenia 13. Architrave 14. Capital 15. Abacus 16. Echinus 17. Column 18. Fluting 19. Stylobate Ionic order Ionic order: 1 - entablature, 2 - column, 3 - cornice, 4 - frieze, 5 - architrave or epistyle, 6 - capital (composed of abacus and volutes), 7 - shaft, 8 - base, 9 - stylobate, 10 - krepis. Corinthian order Valley of the Temples • The Valle dei Templi is an archaeological site in Agrigento (ancient Greek Akragas), Sicily, southern Italy. It is one of the most outstanding examples of Greater Greece art and architecture, and is one of the main attractions of Sicily as well as a national momument of Italy. The area was included in the UNESCO Heritage Site list in 1997. Much of the excavation and restoration of the temples was due to the efforts of archaeologist Domenico Antonio Lo Faso Pietrasanta (1783– 1863), who was the Duke of Serradifalco from 1809 through 1812. • The Valley includes remains of seven temples, all in Doric style. The temples are: • Temple of Juno, built in the 5th century BC and burnt in 406 BC by the Carthaginians. It was usually used for the celebration of weddings. • Temple of Concordia, whose name comes from a Latin inscription found nearby, and which was also built in the 5th century BC. Turned into a church in the 6th century AD, it is now one of the best preserved in the Valley. -

Enforcement of Foreign Cultural Patrimony Laws in US Courts

South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business Volume 4 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall 2007 Enforcement of Foreign Cultural Patrimony Laws in U.S. Courts: Lessons for Museums from the Getty Trial and Cultural Partnership Agreements of 2006 Carrie Betts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Betts, aC rrie (2007) "Enforcement of Foreign Cultural Patrimony Laws in U.S. Courts: Lessons for Museums from the Getty Trial and Cultural Partnership Agreements of 2006," South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENFORCEMENT OF FOREIGN CULTURAL PATRIMONY LAWS IN U.S. COURTS: LESSONS FOR MUSEUMS FROM THE GETTY TRIAL AND CULTURAL PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS OF 2006 CarrieBetts* "Until now we have dreamed, we have slept. Now it is time to wake up." - Maurizio Fiorelli, Italian Prosecutor in the Getty trial.' I. INTRODUCTION Until the former curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Marion True, was indicted on criminal charges and hauled into the Tribunale Penale di Roma for trafficking in stolen antiquities and criminal associations, the modem international trade in looted antiquities barely registered on the radars of most major media outlets. In the wake of the ongoing trial of True in Rome, museums across the U.S.