This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Tah E Dil Se Likhta Hun Yaro, Arz E Musannif Yeh Kaafi Hai, Alfaaz Ke Gehne Hote Hain La Shaoor, Gar Jazba E Dil Na Ho Arz E Sukhan Mein

1. Tah e dil se likhta hun yaro, Arz e musannif yeh kaafi hai, Alfaaz ke gehne hote hain la shaoor, Gar jazba e dil na ho arz e sukhan mein 2. Duago hun yaro baqi ke lamhe yunhi kat te jaayen, Do saans tumhare do mere, kashtiye zeest paar lagayen. 3. Kya dhadakte dil ko zindadili kehte hain? Kya zinda hone ko zindagi kehte hain? Maana, ke saans ka hona zaruri hai , Hum to yaro har pal zindagi ji lete hain. 4 Maujon ne saahil se kaha aamad o raft ke dauran, Hum to aati jaati hain sahara ban ke dikha zara. 5. Zuban ho shirin dil mein dua, Jabin e niyaz hai khuda ki rah. 6. Gar taskin mile tujhe ai raat, teri baahon mein so jaun , Tasavvur tera dil mein rahe, tere rukhsat hone ke baad. 7. Kabhi ro diye kabhi ansoo piye, Tujhe ai zindagi hum muskura kar jiye 8. Us din ka soch ‘ashok’ jab yeh jahan na hoga tere paas, Kis jahan mein hoga tu aur kya hoga tere saath. 10. Lamhe jee raha hun, taqaazaa waqt ka hai, Kaun jaane kitni baqi hai lamhon ki zindagi. 11. Kis naam se pukarun tujhe ai maalik, Har shakhs se nikle hai aah kuch alag. 12. Main jis ko chahun khuda bana lun, Yeh huq hai tumko mujhko bhi? Yaqin ho jis pe khuda wahi hai, Main kyon na yaqin ko khuda bana lun? 13. Jis shauhrat ki hai talab tujhe, woh shauhrat udti chidiya hai, Jis daal pe ja kar panchhi baithe, halki hai woh daal 'ashok'? 14. -

Bol Meri Machli Episode 20

Bol Meri Machli Episode 20 Bol Meri Machli Episode 20 1 / 3 2 / 3 Desi forum tv serials; Meri zindagi hy tu Episode 20 - 7th February 2014; Re: Bol Meri Machli Episode 18; Dramas Episode 5 | Youtube Dramas; Zindagi Udaas ... Man Jalli. Sabz Pari Laal Kabootar. Carry on Humdum. Barish Kay Ansoo. Banjar Drama Serial by G3n1u5. Bol Meri Machli. Bol Meri Machli Episode 15 by sana .... This is a List of Pakistani dramas. The programs are categorized alphabetically. Contents ... Bilqees Kaur · Bin Roye · Bojh (Geo Entertainment); Bol Meri Machli (Geo Entertainment); Boota from Toba Tek Singh · Bulbulay · Bunty I Love You ... bol meri machli episode 1 bol meri machli episode 1, bol meri machli episode 15, bol meri machli episode 25, bol meri machli episode 19, bol meri machli episode 24, bol meri machli episode 16, bol meri machli episode 26, bol meri machli episode 27, bol meri machli episode 17, bol meri machli episode 20, bol meri machli episode 21 Watch Drama Serial Maikay Ko Dedo Sandes by Geo Tv - Episode 70 Watch Online/Download ... tv 20th Novembe; Maikay Ko Dedo Sandes Episode 70 Full on Geo tv 20th November 2015 ... Bol Meri Machli Episode Buri Aurat Episode 3.. Two episodes later, the widow in the serial, titled Dil Toh Bhatkey Ga, gives ... The third drama, Bol Meri Machli, which won an award at the Lux .... More S01E is the one hundred twenty-fourth episode of season one of. ... Bol Meri Machli Episode Buri Aurat Episode 3. Chand Parosa Last Episode.. Maikay Ko Dedo Sandes Episode 68 Har Pal Geo Top Pakistani Drama TV Serial .. -

Of Sixth Edition

BAYAAZ OF SIXTH EDITION All these nohay are available on: www.youtube.com/OldNohay (Links included with the text of each Nauha) Request to recite Surah-e-Fatiha for: Asghar Mirza Changezi (ibne Mirza Mumtaz Hussain) Noor Jehan Begum (binte Syed Wirasat Ali Rizvi) Agha Meher Qasim Qizalbash (ibne Agha Mumtaz Hussain) Naveed Banoo, Saeed Banoo & Fahmeed Banoo (binte Raza Haider Rizvi) All the Shayar E Ahlebait and Nauhakhwans who have passed away And All Momineen and Mominaat English Transliteration of Contents 1. Janab Aale Raza .................................................................................. 13 1.1. Pukari laash pe Zehra mere Hussain Hussain ....................................................13 1.2. Salaam Khak-na shi no n-pa .......................................................................................13 2. Janab Afsar Lucknowi Sahib ............................................................... 15 2.1. Raat aadhi aa gayi ai Jaan e Madar ghar mein aao .........................................15 3. Janab Ahsan Tabatabai Sahib ............................................................. 16 3.1. Karbala aaye thay Shah, Dunia se jaane ke liye ................................................16 4. Janab Ali Raza Baqri Sahib ................................................................. 17 4.1. Asghar Huñ Maiñ Asghar .........................................................................................17 5. Mohtarma Akthar Sahiba .................................................................... 18 5.1. -

Zaroorat E Mazhab

Aqaid Chapter 1 ZAROORAT E MAZHAB Darakht jungle mein bhi ugte hain, baagh aur chaman mein bhi lagaye jate hain, liken jungle mein aadmi jaate huwe darta hai aur baagh mein jane ko iska jee chahta hai. Yeh sirf is liye hai ki jungle mein kisi qayda aur qanoon ke baghair darakht ugte hain, aur baagh mein qayde se lagaye jate hain. Jungle mein koi maali darakhton ki dekh bhaal nahi karta hai aur baagh mein maali darakhton ki dekhbhaal karta hai. Insaanon ko bhi agar baghair qayda aur qanoon ke jeene ka mauqa diya jaye to insano ki aabaadi bhi jungle ka namuna ban jayegi aur agar qayda aur qanoon se log zindagi basar karenge to aadmiyon ki bastiyan jannat ka namoona ban jayengi. Lihaza zaroorat hai aise qanoon ki jo insaan ko jine ka tareeqa bataye aur isi qanoon ka naam mazhab hai Insanon ke is chaman ke baaghbaan Nabi aur Imam hote hain jinko Khuda ne hamesha hamari hidayat ke liye bheja hai. M06 Page AQA-1 v3.00 Aqaid Chapter 2 KYA KHUDA NAHI HAI ? Islami dunya mein jahan be shumaar mazhab wale paaye jaate hain wahan kuch log la mazhab bhi hai. Ye log apne aap ko “Dehriya” kehte hain. Inka khayal hai ke yah dunya baghair kisi khuda ke ek din aap hi aap paida ho gayi hai aur ek din ayega jab aap hi aap mitt jayegi In logon ke samne dunya ki koi cheez aisi nahi hai jiske liye kaha ja sake ye khud ba khud paida ho gayee hai laiken sirf khuda ka inkaar karne ke liye yeh kehne lage hain ke yeh puri dunya baghair paida karne wale ke paida ho gayi hai Hamare chatte (6th) Imam Jafar e Saadiq (as) ke paas ek dehriya aaya jiska naam Abdullah Dehsani tha. -

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02-2018 108 TEERTH YATRA Sony Wah TV004 07-05-2017 1234 Zee Talkies HD TV005 18-06-2017 13 NO TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla HD TV006 27-09-2015 13 NUMBER TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla Cinema TV007 25-08-2016 2012 RETURNS Zee Action TV008 02-07-2015 22 SE SHRAVAN Jalsha Movies TV009 04-04-2017 22 SE SRABON Jalsha Movies HD TV010 24-09-2016 27 DOWN Zee Classic TV011 26-12-2018 27 MAVALLI CIRCLE Star Suvarna Plus TV012 28-08-2016 3 AM THE HOUR OF THE DEAD Zee Cinema HD TV013 04-01-2016 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIKA Zee Talkies TV014 22-06-2017 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIYKA Zee Talkies TV015 21-02-2016 3 GUTTU ONDHU SULLU ONDHU Star Suvarna TV016 12-05-2017 3 GUTTU ONDU SULLU ONDU NIJA Star Suvarna Plus TV017 26-08-2017 31ST OCTOBER STAR Gold Select HD TV018 25-07-2015 3G Sony MIX TV019 01-04-2016 3NE CLASS MANJA B COM BHAGYA Star Suvarna TV020 03-12-2015 4 STUDENTS STAR Vijay TV021 04-08-2018 400 Star Suvarna Plus TV022 05-11-2015 5 IDIOTS Star Suvarna Plus TV023 27-02-2017 50 LAKH Sony Wah TV024 13-03-2017 6 CANDLES Zee Tamil TV025 02-01-2016 6 MELUGUVATHIGAL Zee Tamil TV026 05-12-2016 6 TA NAGAD Jalsha Movies TV027 10-01-2016 6-5=2 Star Suvarna TV028 27-08-2015 7 O CLOCK Zee Kannada TV029 02-03-2016 7 SAAL BAAD Sony Pal TV030 01-04-2017 73 SHAANTHI NIVAASA Zee Kannada TV031 04-01-2016 73 SHANTI NIVASA Zee Kannada TV032 09-06-2018 8 THOTAKKAL STAR Gold HD TV033 28-01-2016 9 MAHINE 9 DIWAS Zee Talkies TV034 10-02-2018 A Zee Kannada TV035 20-08-2017 -

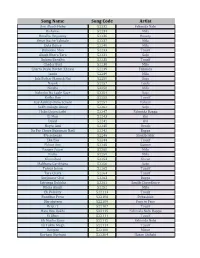

Song Name Song Code Artist

Song Name Song Code Artist Ami Akash Hobo 52232 Fahmida Nabi Bishshas 52234 Mila Bondhu Doyamoy 52236 Beauty Bristi Nache Taletale 52237 Mila Dola Dance 52240 Mila Bishonno Mon 52233 Tausif Akash Bhora Tara 52231 Saju Bolona Bondhu 52235 Tausif Chader Buri 52238 Mila Charta Deyal Hothat Kheyal 52239 Fahmida Jaadu 52249 Mila Jala Bojhar Manush Nai 52250 Saju Nayok 52257 Leela Nirobe 52258 Mila Kolonko Na Lagle Gaye 52254 Saju Kotha Dao 52255 Tausif Kay Aankay Onno Schobi 52251 Tahsan Sokhi Bologo Amay 52262 Saju Hobo Dujon Sathi 52247 Fahmida Bappa Ei Mon 52243 Oni Doyal 52241 Ovi Hoyto Ami 52248 Ornob Du Par Chuya Bohoman Nadi 52242 Bappa Eto sohosay 52246 Shakib Jakir Eka Eka 52244 Tausif Ekhon Ami 52245 Sumon Paaper Pujari 52260 Mila Nisha 52259 Mila Khunshuti 52253 Shuvo Malikana Garikhana 52256 Saju Tomar Jonno 52265 Tausif Tare Chara 52264 Tausif Surjosane Chol 52263 Bappa Satranga Dukkha 52261 Sanjib Chowdhury Khola Akash 52252 Mila Ek Polokey 522113 Tausif Bondhur Prem 522106 Debashish Dhrubotara 522109 Face to Face Bristi 2 522107 Tausif Hate Deo Rakhi 522115 Fahmida Nobi Bappa Ei Jibon 522111 Tausif Ek Mutho Gaan 522112 Fahmida Nobi Ek Tukro Megh 522114 Tausif Danpite 522108 Minar Kurbani Kurbani 522304 Hasan Shihabi Premchara Cholena Duniya 522342 Saju Rodela Dupur 522348 Tahsan Mithila Jeona Durey Chole 522280 Bappa Toni Khachar Bhitor Ochin Pakhi 522291 Labonno Kumari 522303 Shohor Bondi Nach mayuri nach re 522341 Labonno Tumi Amar 522381 Shahed Chandkumari 522385 Purno Soilo Soi 522391 Purno Itihas 71 522534 ROCK 404 Chandrabindu -

Nouhejat Anjumane Ansarul Mehdi

NOUHEJAT ANJUMANE ANSARUL MEHDI (AS) 1435 H (2013/2014) Fremont, California. USA (Ver. 4) 1 1. ANSARE MEHDI KARTI HAI SHABBEER KA MATAM 4 2. IS TARAH SE SADIYON PE NA PHAILA KOI GHAM AUR 6 3. DIN HAI AZA KE LOGO FARSHE AZA BICHAO 7 4. KARBALA MAKUNTO MOULA 8 5. HUSSAIN NO MINNI WANA MINAL HUSSAIN 11 6. MARHABA HUSSAIN JANE FATIMA 12 7. YE HAI WAQAYATE KARBALA YAHAN FATIMA KA GHAR LUTA 13 8. GAZI ABBAS KE PURCHAM KO UTAHTE RAHEINA 15 9. KARBALA KUCH TO BATA! KARBALA KUCH TO BATA 16 10. AYE MOMINO PAYAME SARWAR KO YAAD RAKHNA 17 11. AYE HURRE DILWAR MERE, AYE HURRE DILAWARE 19 12. LADNE KO JAA RAHE HAIN ZAINAB KE LAAL DONO 20 13. AYE AUNO MOHD MERA 21 14. LAILA KI JAAN SHAIH KE PISAR AKBARE JAWAN 22 15. PAIWAST JO AKBAR KE KALEJE ME SINA HAI 23 16. AKBAR CHALA HAI MARNE KO KOI BADE KE OS KO RUKLO 24 17. HAYE AKBAR KAISE JIYE TERI MAA AKBAR 25 18. AKBAR AYE JAANE MADAR 26 19. NAJANE KIS TERHA LAILA NE DEKHA 27 20. BETA JAWAN RAGADTA HUA YEDIYAN MILA 28 21. GHOONJI HAI KARBALA MEIN AKBARE TERI AZAAN 30 22. PALAT KAR DEKHTE AYE LAL JAO 31 23. DUA KARO MERA NOORE NAZER PALAT AYE 32 24. AYE ALI KE LAL SAKHAYE HARAM 33 25. LAHU DOOB GAYA 34 26. RUN MEIN HAWA KE JHUKE 35 27. KARBALA MEIN HUA LAQTE 36 28. BAICHAIN HO RAHI HAI ROHE HASAN KAFAN MEIN 37 29. FARWA KA LAAL RAN MEIN TUKDAON MEIN BAT GAYA HAI 38 30. -

Noor -E- Panjatan

NOOR -E- PANJATAN A COMPILATION OF NAUHAS, MARSIYAS, MANQABATS, QASIDAS, DUAS AND A’MAALS. (VOLUME A-2018) TABLE OF CONTENTS NAUHAS AND MARSIYAS GENERAL: AY RABBE JAHAAN 2 SHAMMA SE SHAMMA 3 AY MAAHE MUHARRAM TUHI 4 MUJRAI KHALQ MEIN 5 SUGHRA KO RULAATA HAI 6 KULSUM NE MEHMIL KE 7 WAWELA HAY WAWELA 8 YA RAB BIHAKKE ZEHRA 9 MAWLAYA YA MAWLAYA (ENGLISH) 10 AY FARISHTO MUJE 11 ASSALAMU ALAL HUSSAIN 12 I WILL COME CRAWLING TO YOU HUSSAIN 13 KYA RAHA KHAIMON 14 JAA RAHAAHU 15 SALAAM KHAAK NASHINOPE 16 MAUT KI AAGOSH MEIN (MAA) 17 TAMAAM AALAM 18 APNI KISMAT AAZMA KAR 19 BIKHDE PADE HAI LAASHE 20 SHEHRE SARWAR KI AABO 21 AAJ KABRE MUSTAFA PAR 22 BANO KAHAAN TALASH 23 NA ABH HUSSAIN NA 24 JAA RAHA HAI 25 HASHR ME RANG LAIGA 26 CHEHLUM KO KERBALA ME 27 SAAYE ME SAYYADA KE 28 ALLAH MUJE LASHKARE MEHDI 29 DUA-E MANG RAHA HU 30 KERBOBALA NASEEB SE JAANA 31 HAM HUSSAIN WAALE HAIN 32 GHAM KA ILAAJ ISKE 33 CHAWDA SADIYAN BEET GAYI 34 TABLE OF CONTENTS NAUHAS AND MARSIYAS GENERAL: AABAAD HUI KERBOBALA 35 KARBALA TAAZIM KAR 36 ZAHRA KI BETIYON KI RIDAAEN 37 SHAAME GHARIBA: AY SHIA YUN IMSHAB 38 KYA RAHAA KHAIMO ME 39 SHAME GHURBAT ME BACHI PUKAARI 40 IMAM ALI (A.S.): IBNE MULJIM NE HAIDER KO 41 IMAM HUSSAIN (A.S.): ZULJANAH AY ZULJANAH 42 SHABBIR TERA YE MAATAM 43 AY MUSALMAAN KAASH SOCHA 44 HUSSAIN AL GHAREEB (URDU) 45 HUSSAIN AL GHAREEB (ENGLISH) 46 SURA-E-KAHF SUNAATA HAI 47 YE JITNE SHAH TAWANGAR 48 MERE BABA KHAIRIAT SE HO 49 YE FALAK SE AATI THI SADAA 50 BANKE SAAIL AAYE HAI 51 YA HUSSAIN MERI FARYAD SUNLO 52 HAMSE GHAME SHABBIR 53 SHABBIR TERI -

Ahsaan O Tasawwuf (Roman)

Ahsaan O Tasawwuf (Roman) KHWAJA SHAMS -UD-DIN AZEEMI 1 Ahsan o Tasawwuf AHSAAN O TASAWWUF KHAWAJA SHAMSUDDIN AZEEMI www.ksars.org www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 2 Ahsan o Tasawwuf INTISAAB KAAINAAT MAIN PEHLE SUFI HAZRAT AADAM ALEH ASSLAAM KE NAAM www.ksars.org www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 3 Ahsan o Tasawwuf KHULAASAH Har Shaks Ki Zindigi Rooh Ke Taabe Hai Aur Rooh Azal Main Allah Ko Dekh Chuki Hai Jo Bandah Apni Rooh Se Waaqif Ho Jaata Hai Who Is Duniya Main Allah Ko Dekh Leta Hai www.ksars.org www.ksars.org Khwaja Shamsuddin Azeemi Research Society 4 Ahsan o Tasawwuf TAARUF Bism Allah al-rehman alraheem Tasawuf ki haqeeqat, sufia karaam aur aulia Azaam ki sawanah, un ki talemaat aur masharti kirdaar ke hawalay se bohat kuch likha gaya aur naqideen ke giroh ne tasawuf ko bzam khud aik uljha huamaamla saabit karne ki koshish ki lekin is ke bawajood tasawuf ke misbet asraat har jagah mehsoos kiye gaye. Aaj muslim amh ki haalat par nazar dorhayin to pata chalta hai ke hamari umomi sorat e haal Zaboon haali ka shikaar hai. Guzashta sadi mein aqwam maghrib ne jis terhan science aur technology mein Awj kamaal haasil kya sab ko maloom hai ab chahiye to yeh tha ke musalman mumalik bhi roshan khyaali aur jiddat ki raah apna kar apne liye maqam peda karte aur is ke sath sath Shariat o tareqat ki roshni mein apni maadi taraqqi ko ikhlaqi qawaneen ka paband bana kar saari duniya ke samnay aik namona paish karte aik aisa namona jis mein fard ko nah sirf muashi aasoudgi haasil ho balkay woh sukoon ki doulat se bhi behra war ho magar afsos aisa nahi ho saka. -

Phonologies of Various Languages

PHONOLOGIES OF VARIOUS LANGUAGES Maqsood Hasni COTENTS 01- Preface 02- No language remains in one state 03- The common compound souds of languages 04- The identitical sounds used in Urdu 05- Some compound sounds in Urdu 06- Compound sounds in Urdu (2) 07- The Idiomatic association of Urdu and English 08- The exchange of sounds in some vernacular languages 9- The effects of Persian on Modern Sindhi 10- The similar rules of making plurals in indigious and foreign languages 11- The common compounds of indigious and foreign languages 12- The trend of droping or adding sounds 13- The languages are in fact the result of sounds 14- Urdu and Japanese sound’s similirties 15- Other languages have a natural link with Japanese’s sounds SUPLIMENTS 1- Present research is attached with the achievement of degree 2- Need changes in educational systems of the delovping countries 3- Man does not live in his own land 4- A person is related to the whole universe 5- Where ever a person 6- Linguistic set up is provided by poetry 7- How to resolve problems of native and second language 8- A student must be instigated to do something himself 9- Languages never die tillits two speakers 10- A language and society don’t delovp in days 11- Poet can not keep himself aloof from the universe Preface Money, woman and land have made man selfish and materialist. Man has been divided socially by social chiefs, religiously by the cacique of religions, politically by the political pundits, linguistically by the so called language researchers, and with respect to land by the landlords, and this process is not new but centuries old. -

A Collection of the Most Famous Na'ats in English

A COLLECTION OF THE MOST FAMOUS NA’ATS IN ENGLISH COMPILED WITH ENGLISH TRANSLITERATION ROMAN HUROOF (LETTERS) MEIN URDU TAHREER (WRITING) BY ZAKIR HUSSAIN KAPADIA, PhD This is a book of a life time and it is unique. It contains well over 300, Hamds, Na’ats, various Salaams upon the Prophet; Hazrat Muhammad Mustafa (SAW), Manqabats, and above all Na’ats written by As Sahaabah, Taabi’un, Tabi‘ al-Tabi‘in and Auliya Allah, ‘et al; reproduced from the original manuscripts. The book also contains Na’at Stalwarts, such as H. Imaame Aa‘zam Abu Hanifa, Jami, Saa‘di Shirazi, as well as contemporary, distinguished writers such as Janaab Aala Hazrat, Allama Hasan Raza Khan, Allama Iqbal,Niazi, Zahoori, Khaled, Taib, Adeeb, Saim, Iqbal A’zam, Riaz, Akbar Warsi, Naseer; et al. All rights are reserved under National and International Copyright Conventions. No part Of this book may be reproduced in any form Without written permission of the translator. First Edition: 2018 Printed By: Shirkat Printing Press Nisbat Road Lahore, Pakistan. ISBN: 978-969-534-253-4 i Contents 1. AUTHOR’S PREFACE .................................................................................................................. 1 2. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 NOTES ON URDU GRAMMAR ....................................................................................................... 1 2.2 PRONUNCIATION AND TRANSLITERATION ....................................................................................