Read an Extract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publishers Who Translate in the UK and Ireland

Appendix C: Publishers who translate in the UK and Ireland This list has been compiled by the literature department of Arts Council England (ACE) and was expanded and updated by Literature Across Frontiers (LAF). Both organisations have made have made every attempt to ensure that the information in the list is complete and up to date, and bear no responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies. Please note that the list is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive. Inclusion in the list is by way of information only and does not necessarily constitute an endorsement by ACE or LAF. Please contact us at resources@lit-across- frontiers.org with any factual corrections. ENGLAND And Other Stories www.andotherstories.org Launched in 2010, And Other Stories publishes fiction in translation with support from the Arts Council of England and its list of subscribers. They are a social enterprise, and choose fiction for its originality and appeal after listening carefully to their circles of readers, writers and translators, many of whom are eminent figures in their field. They choose to publish only a carefully selected handful of titles each year. Alma Books www.almabooks.com Alma Books was set up in October 2005 by Alessandro Gallenzi and Elisabetta Minervini, the founders of Hesperus Press. Publishing from fifteen to twenty titles a year, mainly in the field of contemporary literary fiction, Alma takes around sixty per cent of its titles from English-language originals, while the rest are translations from other languages such as French, Spanish, Italian, German and Japanese. Alma also publishes two or three non-fiction titles each year. -

Frankfurt Book Fair 2015

THE GRAYHAWK AGENCY FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR 2015 THE GRAYHAWK AGENCY FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR 2015 CHINESE & TAIWANESE AUTHORS OUR TABLE: 14N @ H6.3 LitAg Contact: Gray Tan [email protected] 0 THE GRAYHAWK AGENCY FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR 2015 PRIVATE EYES A Crime Novel by Chi Wei-Jan (Taiwan) Translated by Anna Holmwood and Gigi Chang *A bestseller with over 10,000 copies sold *Major Chinese-language film in development *Winner of the Taipei Book Fair Award *Winner of the China Times Open Book Award *Asia Weekly Top Ten Chinese Novel of the Year *Official “Books From Taiwan” Selection “Taipei is both a curse and a miracle. I wondered which 紀蔚然・私家偵探 higher power it was that sustained me, so that I might take shelter in this chaotic universe, and what was the magical Publisher: Ink (2011) mechanism that enabled our crystalline civilization to Pages: 352pp overcome each disaster in turn?” Full English translation available Length: 100,000 words (English) Winner of the top three literary awards in Taiwan, Chi US: Markus Hoffmann (Regal Wei-Jan’s PRIVATE EYES is a brilliant literary crime novel in Hoffmann & Associates) which Wu Cheng, a failed-academic-turned-sleuth, tries to make sense of the absurdity of modern city life and to prove his innocence in a series of murders. The first ever serial RIGHTS SOLD killer in Taiwan, a family scandal that leads to corruptions of the social health insurance system and a Buddhist fanatic WRITERS PUBLISHING (CHINA) who turns to killing people as a way of “salvation” are only KAHVE (TURKEY) part of the charm of this hilarious and darkly delicious novel. -

Emily O'grady Thesis

Subverting the Serial Gaze: Interrogating the Legacies of Intergenerational Violence in Serial Killer Narratives Emily O’Grady Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) Creative Industries: Creative Writing and Literary Studies Queensland University of Technology Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 1 Abstract This thesis subverts, disrupts and reimagines dominant narratives of fictional serial crime through a hybrid research paradigm of creative practice and critical analysis. The creative output of this thesis is an 80,000 word literary novel titled The Yellow House, accompanied by a 20,000 word critical exegesis. In the following, I argue that current fictional iterations of the serial killer literary genre are rigidly conservative, and remain fixed within the safe confines of genre conventions wherein the narrative bears little resemblance to how abject violence and the aftermath of serial crime plays out in real life. The broad framework of genre theory, accompanied by trauma theory, allows for an examination of the serial killer genre to identify the space in which my creative practice—an Australian, literary rendering of serial crime—fits as an extension and subversion of the genre. By reimagining the Australian serial killer narrative, I seek to challenge the reductive serial killer genre, and come to a potential offering of serial homicide that interrogates how the legacies of abject violence can be transmitted across generations. I do this by shifting the focus onto the aftermath of the crime and its numerous victims—in particular, the descendants of serial killers. The Yellow House presents a destabilising fictionalisation of serial crime that disrupts the conventions of the genre in order to contend with the complexity and instability of serial homicide. -

The Angel of Ferrara

The Angel of Ferrara Benjamin Woolley Goldsmith’s College, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own Benjamin Woolley Date: 1st October, 2014 Abstract This thesis comprises two parts: an extract of The Angel of Ferrara, a historical novel, and a critical component entitled What is history doing in Fiction? The novel is set in Ferrara in February, 1579, an Italian city at the height of its powers but deep in debt. Amid the aristocratic pomp and popular festivities surrounding the duke’s wedding to his third wife, the secret child of the city’s most celebrated singer goes missing. A street-smart debt collector and lovelorn bureaucrat are drawn into her increasingly desperate attempts to find her son, their efforts uncovering the brutal instruments of ostentation and domination that gave rise to what we now know as the Renaissance. In the critical component, I draw on the experience of writing The Angel of Ferrara and nonfiction works to explore the relationship between history and fiction. Beginning with a survey of the development of historical fiction since the inception of the genre’s modern form with the Walter Scott’s Waverley, I analyse the various paratextual interventions—prefaces, authors’ notes, acknowledgements—authors have used to explore and explain the use of factual research in their works. I draw on this to reflect in more detail at how research shaped the writing of the Angel of Ferrara and other recent historical novels, in particular Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. -

2021 Edition Alzheimer’S Disease

2021 EDITION ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE QUALITY HEALTH RELATED INFORMATION CAREFULLY SELECTED BY YOUR LIBRARIES 2 ABOUT COORDINATION – QUEBEC PUBLIC Biblio-Santé is a program of the Quebec Public Library LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Association. The ABPQ is made up of more than 179 member Clémence Tremblay-Lebeau, Project manager municipalities and corporations, for a total of over BIBLIOGRAPHIC RESEARCH 317 autonomous libraries. Biblio-Aidants is available in more than 780 participating public libraries as well as Gabrielle C. Beaulieu, Project manager Audrey Scott, Intern librarian associated health libraries throughout Quebec. Visit our Clémence Tremblay-Lebeau, Project manager website to see if your library participates in the program. CONTENT REVIEW AND EDITING ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Sandra Cliche-Galarza, Intern librarian Biblio-Santé is an initiative of the Charlemagne, L’Assomption Fannie Labonté, Member services and events coordinator and Repentigny libraries that was started under the name Clémence Tremblay-Lebeau, Project manager Biblio-Aidants. The Quebec Public Library Association would like to thank these three cities for allowing it to extend the LAYOUT AND DESIGN program to the rest of Quebec by transferring the copyright. Steve Poutré DGA VISIT OUR WEBSITE You will find all of the Biblio-Santé booklets and additional information. bibliosante.ca The information provided does not replace a diagnosis or medical examination by a physician or qualified health professional. The content of this booklet was verified in the spring of 2021 and will be -

Download 2020 Iread Resource Guide Home Edition

iREADiREAD HOMEHOME EDITIONEDITION 20202020 2021iREAD Summer Reading The theme for iREAD’s 2021 summer reading program is Reading Colors Your World. The broad motif of “colors” provides a context for exploring humanity, nature, culture, and science, as well as developing programming that demonstrates how libraries and reading can expand your world through kindness, growth, and community. Readers will be encouraged to be creative, try new things, explore art, and find beauty in diversity. Illustrations and posters tell the story: Read a book and color your world! Artwork ©2019 Hervé Tullet [www.sayzoop.com] for iREAD®. iREAD® (Illinois Reading Enrichment and Development) is an annual project of the Illinois Library Association, the voice for Illinois libraries and the millions who depend on them. It provides leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library services in Illinois and for the library community in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. The goal of this reading program is to instill the enjoyment of reading and to promote reading as a lifelong pastime. Dig Deeper: Read, Investigate, Discover; Reading Colors Your World and all associated materials ©2019 Illinois Library Association. DIG DEEPER: READ, INVESTIGATE, DISCOVER 2020 iREAD® Resource Guide Portia Latalladi 2020 iREAD® Chair Alexandra Annen 2021 iREAD® Chair Becca Boland 2022 iREAD® Chair Brandi Smits 2020 iREAD® Ambassador Sarah Rice Resource Guide Coordinator David Roberts Pre-K Program Illustrator Rafael López Children’s Program Illustrator Alleanna Harris Young Adult Program Illustrator Jingo de la Rosa Adult Program Program Illustrator Diane Foote Executive Director, Illinois Library Association A PRODUCTION OF THE ILLINOIS LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. -

Activism, Growth of Small Independent Publishers Leading to 'Profound Change' for Translated Fiction, Research Shows 27 February 2020

Activism, growth of small independent publishers leading to 'profound change' for translated fiction, research shows 27 February 2020 Activism, new networks and the growth of small trend awayfrom them either. independent presses is leading to profound change in the way translated fiction is published, a Dr. Mansell said: "This data indicates more prestige new study shows. is still amassed by the big five publishers in non- translated fiction, but it shows change is happening The research also shows the extent to which books right now in translated fiction. Positions of power of written by male writers have dominated prestigious publishers are not as stable as they were. On the award longlists for the past two decades, with an one hand, this has provoked changing practices even greater gender gap for translated fiction. amongst some of the big five, such as HarperCollins's decision to launch Harper Via, an Dr. Richard Mansell, from the University of Exeter, imprint dedicated to translated fiction. On the other, examined data from the 272 titles longlisted for the it demonstrates that translated fiction is a more Man Booker International Prize (2016-2019) and its fertile ground for success for small independent predecessor the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize publishers." (2001-2015) for translated fiction, and the 292 titles longlisted for the (Man) Booker Prize between The study says an important reason why small 2001 and 2019. independent publishers are growing is because of the way they discover and promote authors and The data shows the largest publishers' dominance titles thanks to networks of writers and translators, on the longlists has waned for translated fiction. -

Vintage Michael Joseph Transworld

VINTAGE MICHAEL JOSEPH PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE TRANSLATION RIGHTS GUIDE TRANSWORLD London Book Fair 2020 Translation Rights Michael Joseph specialises in women’s fiction, crime, thrillers, cookery, memoirs and lifestyle books. Many of its authors are now, or soon will be, household names in the UK and around the world. GENERAL FICTION Michael Joseph specialises in women’s fiction, publishing established brands like Marian Keyes, Jojo Moyes, Liane Moriarty, Conn Iggulden and Fredrik Backman as well as signing and launching debut novelists. Other authors include Dawn French, Sylvia Day, Giovanna Fletcher, Stephen Fry and Lesley Pearse. CRIME FICTION Michael Joseph publishes crime fiction by authors at home on the bestseller lists, whether they’re up-and- coming or established in the genre, including M.J. Arlidge, Tim Weaver, Tom Clancy and Clive Cussler. NON-FICTION MEMOIR Either the secrets behind the success of the already famous, or a story that no-one has heard before, the authors writing memoirs include Sue Perkins, Tom Jones, Stephen Fry, Jeremy Clarkson, Michael McIntyre, and Steven Gerrard. COOKERY Whether it is the country’s bestselling cookery writer – Jamie Oliver – or a debut from the brightest and freshest young chefs, Michael Joseph’s list covers everything from gourmet baking to healthy eating, to catering for events or how to eat well on a budget. As well as Jamie Oliver, authors include Rachel Khoo, Nadiya Hussain and Chrissy Teigen. NON-FICTION LIFESTYLE Health and wellbeing is a core specialist area for Michael Joseph, and from exercise and style advice to mindfulness and well-being, its range of publishing is extensive. -

Crime Fiction

└ Index CRIME FICTION Please note that a fund for the promotion of Icelandic literature operates under the auspices of the Icelandic Ministry Forlagid of Education and Culture and subsidizes translations of literature. Rights For further information please write to: Icelandic Literature Center Hverfisgata 54 | 101 Reykjavik Agency Iceland Phone +354 552 8500 [email protected] | www.islit.is BACKLIST crime · 1 · fiction CRIME FICTION crime fiction SIF JOHANNSDOTTIR [email protected] VALGERDUR BENEDIKTSDOTTIR [email protected] · 3 · CRIME FICTION crime Arnaldur Indridason Arni Thorarinsson fiction Jonina Leosdottir Lilja Sigurdardottir Oskar Magnusson Oskar Hrafn Thorvaldsson Ottar M. Nordfjord Solveig Palsdottir Stella Blomkvist Viktor A. Ingolfsson rights-agency · 3 · └ Index CRIME FICTION ARNALDUR INDRIDASON (b.1961) has the rare distinction of having won the Nordic Crime Novel Prize two years running. He is also the winner of the highly respected and world famous CWA Gold Dagger Award for the top crime novel of the year in the English language, Silence of the Grave. Indridason’s novels have sold over twelve million copies worldwide, in 40 languages, and have won numerous well-respected prizes and received rave reviews all over the world. “Yet another masterpiece from Arnaldur. He is exceptional–the Lionel Messi of literature. Arnaldur understands the art of storytelling.” MORGUNBLADID DAILY “He is not called the king of Icelandic crime fiction for nothing ... a superior author.” LITERATURE.IS Petsamo Petsamo, crime novel, 2016 A young woman in Petsamo, Finland waits for known to keep company with the soldiers seems her fiancé to arrive from Copenhagen. They plan to have disappeared. to board the Esjan, sailing home to Iceland and far from the war that has only just made its way Petsamo is Arnaldur Indridason’s twentieth to Scandinavia. -

Publishers Who Translate in the UK and Ireland 2014

Appendix C: Publishers who translate in the UK and Ireland This list has been compiled by the literature department of Arts Council England (ACE) and was expanded and updated by Literature Across Frontiers (LAF). Both organisations have made have made every attempt to ensure that the information in the list is complete and up to date, and bear no responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies. Please note that the list is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive. Inclusion in the list is by way of information only and does not necessarily constitute an endorsement by ACE or LAF. ENGLAND And Other Stories www.andotherstories.org Launched in 2010 by translator Stefan Tobler, And Other Stories publish fiction in translation with support from the Arts Council of England and its list of subscribers. They are a not-for-profit social enterprise, and choose fiction for its originality and appeal after listening carefully to their circles of readers, writers and translators, many of whom are eminent figures in their field. They choose to publish only a carefully selected handful of titles each year. Alma Books www.almabooks.com Alma Books was set up in October 2005 by Alessandro Gallenzi and Elisabetta Minervini, the founders of Hesperus Press. Publishing from fifteen to twenty titles a year, mainly in the field of contemporary literary fiction, Alma takes around sixty per cent of its titles from English-language originals, while the rest are translations from other languages such as French, Spanish, Italian, German and Japanese. Alma also publishes two or three non-fiction titles each year. Anvil Press www.anvilpresspoetry.com Founded in 1968 by Peter Jay and now based in Greenwich, south-east London, Anvil Press is England's longest-standing independent poetry publisher. -

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

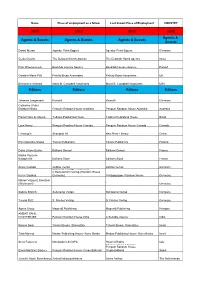

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

The Assault on Journalism Edited by Ulla Carlsson and Reeta Pöyhtäri

The Assault on Journalism on Assault The People who exercise their right to freedom of expression through journalism should be able to practice their work without restrictions. They are, nonetheless, the constant targets of violence and threats. In an era of globalization and digitization, no single party can alone carry the responsibility for protection of journalism and freedom of expression. Instead, this responsibility must be assumed jointly by the state, the courts, media companies and journalist organizations, as well as by NGOs and civil society – on national as well as global levels. To support joint efforts to protect journalism, there is a growing need for research- The Assault based knowledge. Acknowledging this need, the aim of this publication is to highlight and fuel journalist safety as a field of research, to encourage worldwide participation, as well as to inspire further dialogues and new research initiatives. The contributions represent diverse perspectives on both empirical and theoretical on Journalism research and offer many quantitatively and qualitatively informed insights. The articles demonstrate that a new important interdisciplinary research field is in fact Building Knowledge to Protect emerging, and that the fundamental issue remains identical: Violence and threats against journalists constitute an attack on freedom of expression. Freedom of Expression Edited by The publication is the result of collaboration between the UNESCO Chair at the University of Gothenburg, UNESCO, IAMCR and a range of other partners.