The Executive Board of UNESCO: Special Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seafood Market in Italy GLOBEFISH RESEARCH PROGRAMME

The Seafood Market in Italy GLOBEFISH RESEARCH PROGRAMME The Seafood Market in Italy Volum Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fish Products and Industry Division Viale delle Terme di Caracalla e 00153 Rome, Italy Tel.:+39 06 5705 5074 92 Fax: +39 06 5705 5188 www.globefish.org Volume 92 The Seafood Market in Italy by Camillo Catarci (April 2008) The GLOBEFISH Research Programme is an activity initiated by FAO's Fish Utilisation and Marketing Service, Rome, Italy and financed jointly by: - NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service), Washington, DC, USA - FROM, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Madrid, Spain - Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Copenhagen, Denmark - European Commission, Directorate General for Fisheries, Brussels, EU - Norwegian Seafood Export Council, Tromsoe, Norway - OFIMER (Office National Interprofessionnel des Produits de la Mer et de l’Aquaculture), Paris, France - ASMI (Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute), USA - DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans), Canada - SSA (Seafood Services Australia), Australia - Ministry of Fisheries, New Zealand Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, GLOBEFISH, Fish Products and Industry Division Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153Rome, Italy – Tel.: (39) 06570 56313 E-mail: [email protected] - Fax: (39) 0657055188 – http//:www.globefish.org i The designation employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Camillo Catarci; THE SEAFOOD MARKET IN ITALY GLOBEFISH Research Programme, Vol.92 Rome, FAO. -

The Italian Emigration of Modern Times

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2010 The Italian Emigration of Modern Times: Relations Between Italy and the United States Concerning Emigration Policy, Diplomacy, and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment, 1870-1927 Patrizia Fama Stahle University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Stahle, Patrizia Fama, "The Italian Emigration of Modern Times: Relations Between Italy and the United States Concerning Emigration Policy, Diplomacy, and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment, 1870-1927" (2010). Dissertations. 934. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/934 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi THE ITALIAN EMIGRATION OF MODERN TIMES: RELATIONS BETWEENITALY AND THE UNITED STATES CONCERNING EMIGRATION POLICY,DIPLOMACY, AND ANTI-IMMIGRANT SENTIMENT, 1870-1927 by Patrizia Famá Stahle Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 ABSTRACT THE ITALIAN EMIGRATION OF MODERN TIMES: RELATIONS BETWEEN ITALY AND THE UNITED STATES CONCERNING EMIGRATION POLICY, DIPLOMACY, AND ANTI-IMMIGRANT SENTIMENT, 1870-1927 by Patrizia Famà Stahle May 2010 In the late 1800s, the United States was the great destination of Italian emigrants. In North America, employers considered Italians industrious individuals, but held them in low esteem. -

Cultural Diplomacy in Europe

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 102 067 SO 008 107 AUTHOR Haigh, Anthony TITLE Cultural Diplomacy in Europe. INSTITUTION Council for Cultural Cooperation, Strasbourg (France). PUB DATE 74 NOTE 223p. AVAILABLE FROM Manhattan Publishing Co., 225 Lafayette Street, New York, New York 10012 ($9.50) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Exchange; Cultural Interrelationships; *Diplomatic History; European History; Exchange Programs; Foreign Countries; Foreign Policy; *Foreign Relations; *Intercultural Programs; *International Education; Political Science IDENTIFIERS *Europe; France; Germany; Italy; United Kingdom ABSTRACT The evolution of European government activities in the sphere of international cultural relations is examined. Section 1 describes the period between World War I and World War II when European governments tried to enhance their prestige and policies by means of cultural propaganda. Section 2 analyzes the period during World War II when the cohabitation of several exiled governments in the United Kingdom led to the impetus and development of both bilateral and collective forms of cultural diplomacy. The third section deals with the cultural diplomacy of specific countries including France, Italy, the Federal German Republic, and the United Kingdom. French cultural diplomacy is presented at the model, and an attempt is made to show how the other three countries vary from that model. Section 4 examines the collective experiences of three groups of countries in the field of cultural diplomacy. Attention is first given to the largely homogeneous group of five Nordic countries, which evolved a practice of collective cultural diplomacy among themselves. By way of contrast, the seven countries of the Western European Union including Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Luxembourg, the Federal German Republic, and Italy exhibit a system of collective cultural cooperation worked out to implement a clause of a treaty after World War II. -

Pellagra in Late Nineteenth Century Italy: Effects of a Deficiency Disease

Monica GINNAIO* Pellagra in Late Nineteenth Century Italy: Effects of a Deficiency Disease Pellagra, a nutritional defi ciency disease linked to a defi cit in vitamin B3 (niacin), affected – and until recently continued to affect – poor populations whose diet consisted almost exclusively of maize (corn) for prolonged periods. It appeared in the eighteenth century, and up to the early twentieth it was still found in parts of Italy, Spain, Portugal, Eastern Europe and the United States. In the twentieth century, pellagra was present in Egypt and some eastern and southern African countries, including South Africa. In this article, which focuses on nineteenth-century Italy and particularly the Veneto, the most severely affected Italian region, Monica GINNAIO reviews the history and epidemiology of the disease, then analyses differences in prevalence and mortality by region, occupational status, age group and sex. She shows the predominance of the disease among the most disadvantaged social groups and women of reproductive age, though no massive impact on fertility has been detected. The main purpose of this study is to identify why the disease known as pellagra, endemic in Italy in the late nineteenth century, was strongly selective by place of residence, occupational category, age and sex. Pellagra is a vitamin defi ciency disease caused by a diet consisting almost exclusively of maize (corn), and was particularly severe among farming families in Veneto and Lombardy from the late eighteenth century to the interwar period. To better understand the social “preferences” of pellagra, this study adopts several analytic perspectives – epidemiology, history, history of medicine, gender studies and social history – thereby bringing to light the connections between the cultural, social and epidemiological factors that led to this selection, a selection that was not without demographic consequences. -

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860

The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN DER KOMMISSION FÜR NEUERE GESCHICHTE ÖSTERREICHS Band 115 Kommission für Neuere Geschichte Österreichs Vorsitzende: em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Brigitte Mazohl Stellvertretender Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Reinhard Stauber Mitglieder: Dr. Franz Adlgasser Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter Becker Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Bruckmüller Univ.-Prof. Dr. Laurence Cole Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margret Friedrich Univ.-Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Garms-Cornides Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michael Gehler Univ.-Doz. Mag. Dr. Andreas Gottsmann Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Grandner em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Hanns Haas Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Wolfgang Häusler Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Ernst Hanisch Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gabriele Haug-Moritz Dr. Michael Hochedlinger Univ.-Prof. Dr. Lothar Höbelt Mag. Thomas Just Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Grete Klingenstein em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Alfred Kohler Univ.-Prof. Dr. Christopher Laferl Gen. Dir. Univ.-Doz. Dr. Wolfgang Maderthaner Dr. Stefan Malfèr Gen. Dir. i. R. H.-Prof. Dr. Lorenz Mikoletzky Dr. Gernot Obersteiner Dr. Hans Petschar em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Helmut Rumpler Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Martin Scheutz em. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gerald Stourzh Univ.-Prof. Dr. Arno Strohmeyer Univ.-Prof. i. R. Dr. Arnold Suppan Univ.-Doz. Dr. Werner Telesko Univ.-Prof. Dr. Thomas Winkelbauer Sekretär: Dr. Christof Aichner The Thun-Hohenstein University Reforms 1849–1860 Conception – Implementation – Aftermath Edited by Christof Aichner and Brigitte Mazohl Published with the support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 397-G28 Open access: Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License. -

150 Years of Plans, Geological Survey and Drilling for the Fréjus to Mont Blanc Tunnels Across the Alpine Chain: an Historical Review

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 140, No. 2 (2021), pp. 169-204, 13 figs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2020.29) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2021 150 years of plans, geological survey and drilling for the Fréjus to Mont Blanc tunnels across the Alpine chain: an historical review GIORGIO V. DAL PIAZ (1) & ALESSIO ARGENTIERI (2) ABSTRACT Geology and tunneling have close interactions and mutual benefits. Preventive geology allow to optimize the technical design, reduce Since Roman age, people living on both sides of the Alps had been costs and minimize bitter surprises. Conversely, systematic survey seeking different ‘north-west passages’, first overriding the mountains during excavation of deep tunnels has provided innovative data for and then moving under them. The first idea of a tunnel under the the advance of geosciences. Mont Blanc was envisaged by de Saussure in 1787. In the 19th century a growing railway network played a fundamental role for the Industrial Revolution, but was hampered for the southern countries KEY WORDS: history of geosciences, Fréjus and Mont Blanc, by the barrier of the Alps, so that modern transalpine railways became transalpine tunnels, Western and Central Alps. essential for the Reign of Sardinia. This paper presents an historical review of first suggestions, projects, field survey, failed attempts and successful drilling works across the Alps, from the Frejus (1871), San Gottardo (1882) and Simplon (1906) railway tunnels to the Grand INTRODUCTION St Bernard (1964) and Mont Blanc (1965) highway tunnels, relived within the advances of regional geology and mapping. The Fréjus tunnel was conceived by Medal, projected by Maus between Modane The ancient roads which ran from Rome to the and Bardonèche and approved by a ministerial commission, but it provinces of the Roman Empire formed a vast network was abandoned due to the insurrection of 1848. -

Padre Agostino Gemelli and the Crusade to Rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part One

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2010 Padre Agostino Gemelli and the crusade to rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part one J. Casey Hammond Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hammond, J. Casey, "Padre Agostino Gemelli and the crusade to rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part one" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3684. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3684 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3684 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Padre Agostino Gemelli and the crusade to rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part one Abstract Padre Agostino Gemelli (1878-1959) was an outstanding figure in Catholic culture and a shrewd operator on many levels in Italy, especially during the Fascist period. Yet he remains little examined or understood. Scholars tend to judge him solely in light of the Fascist regime and mark him as the archetypical clerical fascist. Gemelli founded the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan in 1921, the year before Mussolini came to power, in order to form a new leadership class for a future Catholic state. This religiously motivated political goal was intended to supersede the anticlerical Liberal state established by the unifiers of modern Italy in 1860. After Mussolini signed the Lateran Pacts with the Vatican in 1929, Catholicism became the officialeligion r of Italy and Gemelli’s university, under the patronage of Pope Pius XI (1922-1939), became a laboratory for Catholic social policies by means of which the church might bring the Fascist state in line with canon law and papal teachings. -

Archivio Jacini

Archivio di Stato di Cremona Archivio Jacini Titolo I Famiglia Jacini Revisione 2019 a cura di Silvia Rigato con la collaborazione dei volontari del Servizio Civile Nazionale anno 2017-2018 II L’archivio Jacini è stato depositato in Archivio di Stato nel 2016. Si presentava sostanzialmente già ordinato e corredato da inventari manoscritti redatti a metà Novecento da Francesco Forte, archivista presso l’Archivio di Stato Milano, su incarico di Stefano Jacini. Le carte sono state suddivise da Forte in cinque titoli: Famiglia, Fondi e case, Amministrazione, Ditta Jacini, Miscellanea. In questa sede si propone la trascrizione del primo titolo, diviso a sua volta in gruppi, ciascuno dei quali corrispondente a un membro della famiglia. Nel lavoro di trascrizione e revisione degli inventari, si è cercato il più possibile di rispettare l’ordinamento di Francesco Forte, salvo che per i gruppi 28 e 33, in cui erano state aggiunte a posteriori delle buste in coda a quelle già riordinate ed erano stati scambiati o modificati (aggiunti o sottratti) i contenuti di numerosi fascicoli. In questi casi si è optato per il riordino complessivo del gruppo: rimandiamo pertanto alle note introduttive di queste sezioni per i dettagli. Ove possibile, inoltre, è stata riunita in un unico fascicolo la corrispondenza di uno stesso mittente al fine di alleggerire la descrizione che, pur essendo ancora molto analitica, è ora meno ripetitiva. A fronte dei cambiamenti apportati, il presente inventario riporta sia la nuova fascicolazione, sia le precedenti segnature assegnate da Francesco Forte; in tal modo rimane la possibilità di operare un riscontro con gli inventari manoscritti e al contempo non si perde traccia della loro posizione originaria. -

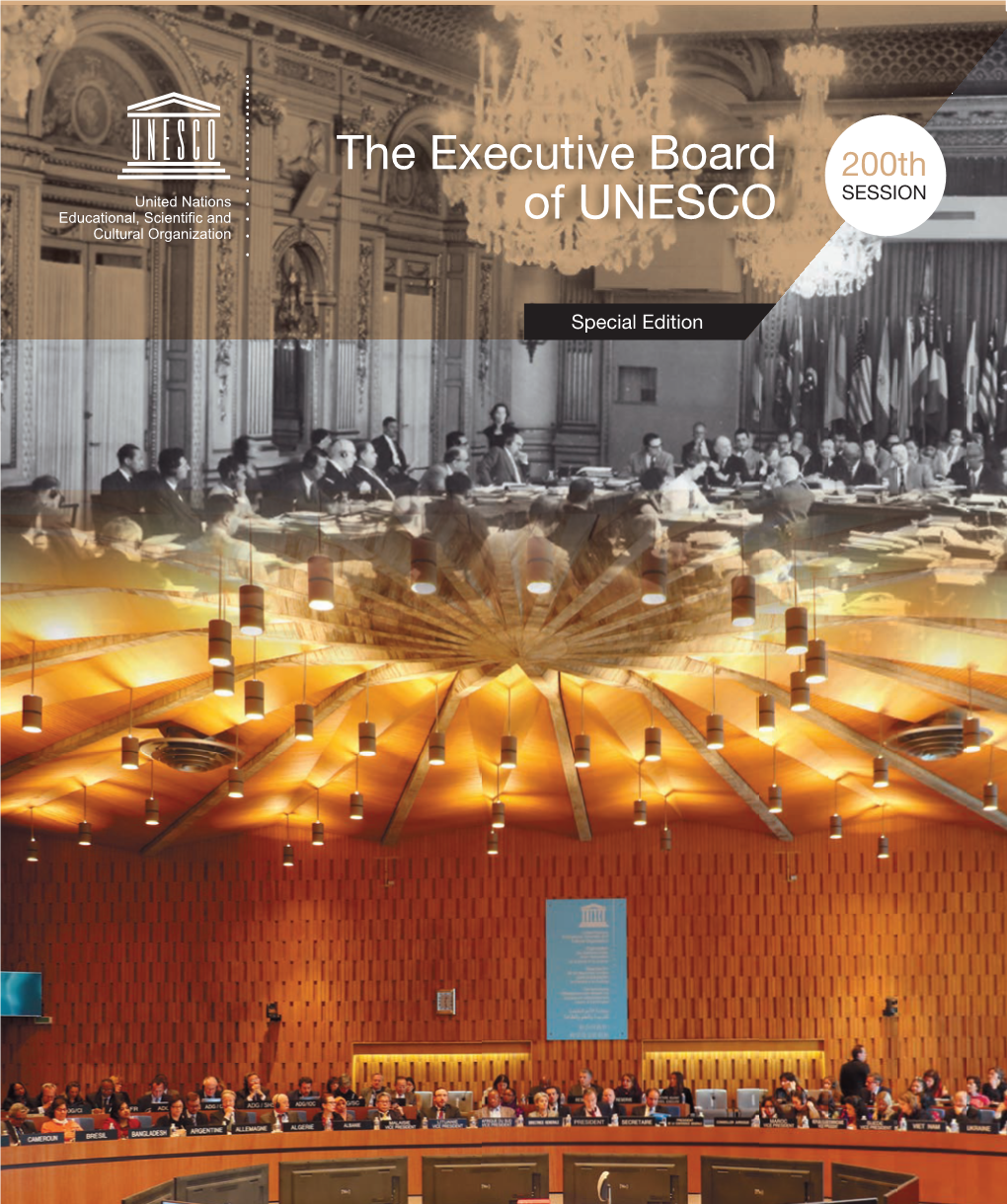

The Executive Board of UNESCO: 2012 Edition; 2012

The Executive Board of UNESCO 2012 Edition The Executive Board of the United Nations Educational, Scientifi c and Cultural Organization The meeting room of the Executive Board, where the delegates sit in a circle, symbolizes the equal dignity of all the Members, while the ceiling design repre- sents the convergence of minds in a single keystone. © UNESCO/Dominique Roger All the terms used in this text to designate the person discharging duties or functions are to be interpreted as implying that men and women are equally eligible to fi ll any post or seat associated with the discharge of these duties and functions. The Executive Board of UNESCO 2012 edition United Nations Educational, Scientifi c and Cultural Organization First published in 1979 and reprinted biennially as a revised edition 16th edition Published in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scientifi c and Cultural Organization Composed and printed in the workshops of UNESCO 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP © UNESCO 2012 SCX/2012/BROCH/CONSEIL EXECUTIF TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................7 III. Structure .............................................18 Subsidiary bodies ....................................18 Commissions ..........................................18 A. Executive Board .................................9 Committees ............................................19 Working and drafting groups......................19 I. Composition .........................................9 Bureau of the Board .................................19 -

The Failure of Italian Nationhood: the Geopolitics of a Troubled Identity Manlio Graziano, September 2010 the Failure of Italian Nationhood

Italian and Italian American Studies Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Series Editor This publishing initiative seeks to bring the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of specialists, general readers, and students. Italian and Italian American Studies (I&IAS) will feature works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices in the academy. This endeavor will help to shape the evolving fields of I&IAS by reemphasizing the connec- tion between the two. The following editorial board consists of esteemed senior scholars who act as advisors to the series editor. REBECCA WEST JOSEPHINE GATTUSO HENDIN University of Chicago New York University FRED GARDAPHÉ PHILIP V. CANNISTRARO† Queens College, CUNY Queens College and the Graduate School, CUNY ALESSANDRO PORTELLI Università di Roma “La Sapienza” Queer Italia: Same-Sex Desire in Italian Literature and Film edited by Gary P. Cestaro, July 2004 Frank Sinatra: History, Identity, and Italian American Culture edited by Stanislao G. Pugliese, October 2004 The Legacy of Primo Levi edited by Stanislao G. Pugliese, December 2004 Italian Colonialism edited by Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Mia Fuller, July 2005 Mussolini’s Rome: Rebuilding the Eternal City Borden W. Painter, Jr., July 2005 Representing Sacco and Vanzetti edited by Jerome H. Delamater and Mary Anne Trasciatti, September 2005 Carlo Tresca: Portrait of a Rebel Nunzio Pernicone, October 2005 Italy in the Age of Pinocchio: Children and Danger in the Liberal Era Carl Ipsen, April 2006 The Empire of Stereotypes: Germaine de Staël and the Idea of Italy Robert Casillo, May 2006 Race and the Nation in Liberal Italy, 1861–1911: Meridionalism, Empire, and Diaspora Aliza S. -

Business Forms, Capital Democratization and Innovation:Ion

Monika Poettinger Bocconi University, Milan BUSINESS FORMS, CAPITAL DEMOCRATIZATION AND INNOVATIONION:::: MILAN IN THE 1850s ABSTRACT Lombardy´s economy in the 1850´s was characterized by extensive networks of personal relations, credit by trust and family businesses. Milan´s wealth was maximized by maintaining the mercantile identity of the city, while manufacturing innovation was pursued only when economic profitable or strategic to further growth. Thanks to a sample including extensive data on almost two hundred firms in existence in Milan from 1852 to 1861, it is possible to reconstruct the mechanisms governing such economy: how liquidity was collected and distributed, how partnerships were formed, inside which social circles were partners found, how much kinship ties determined business decisions, what criteria proved relevant in the investment decision making processes, how were innovation and entrepreneurship rewarded. The picture emerging from the sample will vindicate the capacity of Milan´s mercantile elite to foster innovation through the efficient allocation of capital and the creation of entrepreneurial capital, averting at the same time disastrous financial crises: the solid base of the successive development of the region. Monika Poettinger MILAN IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY “Each sharecropping farm, in Lombardy, produces rice, cheese and silk to be sold for considerable sums, and also every other possible product; it is an inexhaustible land where everything is cheap” 1 Milan´s onlookers in the middle of the nineteenth century saw an incredible richness apparently springing from the surrounding agriculture. Entrepreneurship, on the contrary, was considered scarce 2 and local manufactures judged as hopelessly lagging behind English ones. -

UNESCO. General Conference

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) document. WARNING! Spelling errors might subsist. In order to access to the original document in image form, click on "Original" button on 1st page. RECORDS OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION FIFTH SESSION FLORENCE, 1950 RESOLUTIONS PARIS UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION 19, AVENUE KLEBER, PARIS 16e JULY, 1950 Optical Character Recognition (OCR) document. WARNING! Spelling errors might subsist. In order to access to the original document in image form, click on "Original" button on 1st page. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. MISCELLANEOUS RESOLUTIONS AND DECISIONS . 5 II. RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED ON THE REPORT OF THE PROGRAMME AND BUDGET COMMISSION AND OF THE JOINT COMMISSION-PROGRAMME AND BUDGET, OFFICIAL AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS: First Part: Report of the Rapporteur . , 12 Second Part : Preamble . 15 Third Part: Basic Programme . 24 Fourth Part: The Programme for 1951: 32 Education ....... 32 Natural Sciences ..... 1 . ........... 36 Social Sciences ........ 39 Cultural Activities : : :.. : : 1 . : : 41 Exchange of Persons: ............ : . : . : . 46 Mass Communications .......... 48 Relief Assistance Services ......... : : : : : : 51 Fifth Part: Activities of Unesco in Germany and Japan . 53 Sixth Part: General resolutions. 61 Seventh Part: Technical assistance for the economic development of under- developed countries . 67 Eighth Part: Statement of methods . 69 III. RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED ON THE REPORT OF THE BUDGET COMMITTEE : First Part: Establishment of a Budget Committee for the Sixth Session of the General Conference . _ 77 Second Part: Instructions to the Executive Board and to the Director- General concerning the Programme and Budget . 81 Third Part: Appropiation resolution and appropriation table for 1951 82 IV.