Émile Zola's Volatile Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sos Political Science & Public Administration M.A.Political Science

Sos Political science & Public administration M.A.Political Science II Sem Political Philosophy:Mordan Political Thought, Theory & contemporary Ideologies(201) UNIT-IV Topic Name-Utopian Socialism What is utopian society? • A utopia is an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its citizens.The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. • Utopia focuses on equality in economics, government and justice, though by no means exclusively, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.According to Lyman Tower SargentSargent argues that utopia's nature is inherently contradictory, because societies are not homogenous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. • The term utopia was created from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America Who started utopian socialism? • Charles Fourier was a French socialist who lived from 1772 until 1837 and is credited with being an early Utopian Socialist similar to Robert Owen. He wrote several works related to his socialist ideas which centered on his main idea for society: small communities based on cooperation Definition of utopian socialism • socialism based on a belief that social ownership of the means of production can be achieved by voluntary and peaceful surrender of their holdings by propertied groups What is the goal of utopian societies? • The aim of a utopian society is to promote the highest quality of living possible. The word 'utopia' was coined by the English philosopher, Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 book, Utopia, which is about a fictional island community. -

The Order of the Prophets: Series in Early French Social Science and Socialism

Hist. Sci., xlviii (2010) THE ORDER OF THE PROPHETS: SERIES IN EARLY FRENCH SOCIAL SCIENCE AND SOCIALISM John Tresch University of Pennsylvania Everything that can be thought by the mind or perceived by the senses is necessarily a series.1 According to the editors of an influential text in the history of social science, “in the first half of the nineteenth century the expression series seemed destined to a great philosophical future”.2 The expression itself seems to encourage speculation on destiny. Elements laid out in a temporal sequence ask to be continued through the addition of subsequent terms. “Series” were particularly prominent in the French Restoration and July Monarchy (1815–48) in works announcing a new social science. For example, the physician and republican conspirator J. P. B. Buchez, a former fol- lower of Henri de Saint-Simon who led a movement of Catholic social reform, made “series” central to his Introduction à la science de l’histoire. Mathematical series show a “progression”, not “a simple succession of unrelated numbers”; in human history, we discover two simultaneous series: “one growing, that of good; one diminishing, that of evil.” The inevitability of positive progress was confirmed by recent findings in physiology, zoology and geology. Correlations between the developmental stages of organisms, species, and the Earth were proof that humanity’s presence in the world “was no accident”, and that “labour, devotion and sacrifice” were part of the “universal order”. The “great law of progress” pointed toward a socialist republic in fulfilment both of scripture and of the promise of 1789. -

Embodying Alternatives to Capitalism in the 21St Century

tripleC 16(2): 501-517, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at Embodying Alternatives to Capitalism in the 21st Century Lara Monticelli Independent researcher, [email protected] Abstract: The goal of this article is twofold. First, to illustrate how in the last decade a growing number of critical and Marxist thinkers committed to discussing and developing theories of change have started to broaden their focus by including social movements and grassroots initiatives that are “interstitial”, i.e. initiatives that are developing within capitalism and are striv- ing to prefigure a post-capitalist society in the here and now without engaging in contentious, violent and revolutionary actions and activities. To achieve this, I mainly focus on the work of four authors: Erik Olin Wright, John Holloway, Ana C. Dinerstein, and Luke Martell. The second goal of this article is to understand why these interstitial movements are getting so much at- tention from critical scholars and to argue that the time is ripe for establishing a theory of (and for) prefigurative social movements. The article closes with some brief reflections on the future of radical thinking that includes an invitation, directed mostly at the young generation of critical and Marxist scholars, to begin a dialogue with theories of change developed within other dis- ciplines, to engage with activists, and to experiment with participatory methods and techniques. Keywords: Karl Marx, bicentenary, 200th anniversary, capitalism, crisis, utopia, prefigurative social movements Acknowledgement: The following text constitutes an expanded and revised version of the semi-plenary talk that I gave at the 13th conference of the European Sociological Association (ESA) held in Athens in August 2017. -

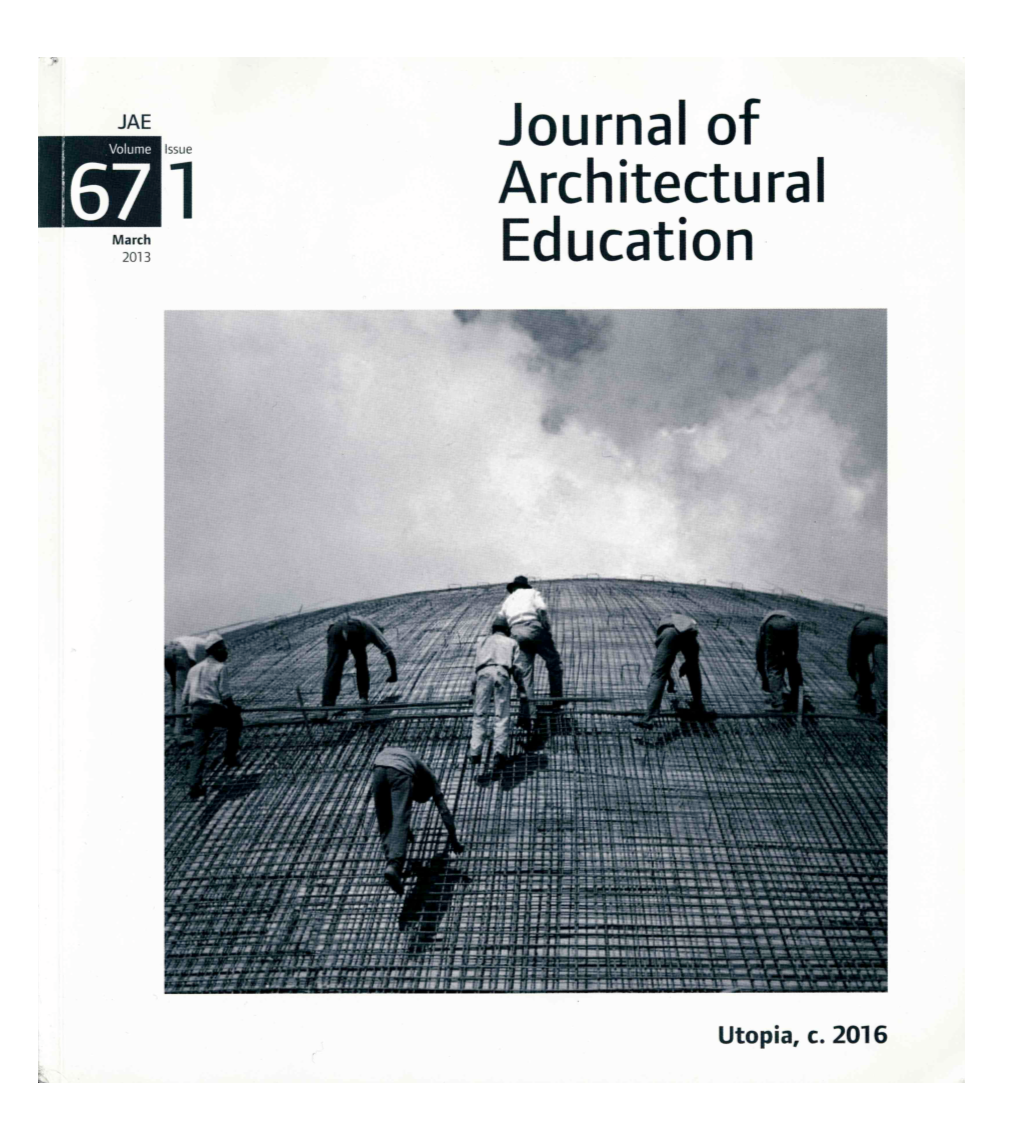

Utopianism and Prefiguration

This item was submitted to Loughborough's Research Repository by the author. Items in Figshare are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated. Utopianism and prefiguration PLEASE CITE THE PUBLISHED VERSION https://cup.columbia.edu/book/political-uses-of-utopia/9780231179591 PUBLISHER © Columbia University Press VERSION AM (Accepted Manuscript) LICENCE CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 REPOSITORY RECORD Kinna, Ruth. 2019. “Utopianism and Prefiguration”. figshare. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/19278. Utopianism and Prefiguration Ruth Kinna For anarchists, utopias are about action. As Uri Gordon argues, utopias are “umbilically connected to the idea of social revolution”.1 The kind of action utopia describes is a matter of debate. This essay examines how utopian thinking shapes anarchist thought and highlights some recent shifts in the political uses of utopia. Utopianism is not treated as an abstract concept or method, nor as a literary genre or place – because that is not how anarchists have understood the idea. Utopia, Gordon notes, “has always meant something more than a hypothetical exercise in designing a perfect society”. As a revolutionary idea, utopia is instead linked to the principle of prefiguration. Prefiguration has been identified as a core concept in contemporary anarchist thinking and it is increasingly invoked to highlight the distinctiveness of anarchist practices, actions and movements. In 2011, two months after the start of Occupy Wall Street, David Graeber identified prefigurative politics as one of the movement’s four characteristically anarchist principles, the other three being direct action, illegalism and the rejection of hierarchy. Hinting at the utopianism of the concept, he described Occupy as a genuine attempt “to create the institutions of the new society in the shell of the old”. -

Rethinking the Failure of the French Fourierist Colony in Dallas

Praktyka Teoretyczna Numer 3(29)/2018 ISSN 2081-8130 DOI: 10.14746/prt.2018.3.6 www.praktykateoretyczna.pl RETHINKING THE FAILURE OF THE FRENCH FOURIERIST COLONY IN DALLAS MICHEL CORDILLOT Abstract: It has generally been accepted that the attempt of the French Fourierists to set up a colony in Texas on the eve of the Civil War was a complete failure. But was that really the case? A reexamination of the colony’s legacy will show that it was more complex and far-reaching than previously thought. Key words: Fourierism, La Réunion, phalanstery, Texas, the 19th century, Victor Considerant Michel Cordillot: Rethinking the failure… Why does the failed attempt of the French Fourierists to set up a socialist colony in Texas on the eve of the Civil War deserve reexamination?1 After all, that colony broke down quickly and might at first sight seem to have been a far from remarkable case on the long list of failed utopian experiments in the history of the United States of America. The point is, however, that when considering its legacy and the consequences that ensued in a broader perspective, the story of Reunion can hardly be written off as a complete disaster. Besides, a reexamination of this largely forgotten episode may also prove helpful in rethinking the problems that appear when yearnings for a brighter future collide with harsh reality. Let us first return to the context in which a group of European followers of the French social philosopher Charles Fourier (1772-1837) decided to cross the Atlantic ocean in 1855 to settle in the middle of nowhere in the Texan prairie to found Reunion under the guidance of his main disciple, Victor Considerant.2 This attempt took place a few years after Louis- Napoléon Bonaparte’s violent seizure of power in France on December 2, 1851. -

Socialist Anti-Semitism, Defense of a Bourgeois Jew and Discovery of the Jewish Proletariat Changing Attitudes of French Socialists Before 1914*

NANCY L. GREEN SOCIALIST ANTI-SEMITISM, DEFENSE OF A BOURGEOIS JEW AND DISCOVERY OF THE JEWISH PROLETARIAT CHANGING ATTITUDES OF FRENCH SOCIALISTS BEFORE 1914* The anti-Semitism of the mid-nineteenth-century French socialists has often been cited. Charles Fourier saw the Jews as the incarnation of commerce: parasitical, deceitful, traitorous and unproductive. Pierre- Joseph Proudhon attacked the Jews even more violently, declaring the Jew the incarnation of finance capitalism and "by temperament an anti-pro- ducer". The Fourierist Alphonse Toussenel argued in Les Juifs rois de I'epoque that finance, that is to say, Jews, were dominating and ruining France, while Auguste Blanqui sprinkled his correspondence with remarks about Jewish usury and "Shylocks", and in a general anticlerical critique blamed the Jews for having given birth to Catholicism, an even greater evil than Judaism. In the late 1860's Gustave Tridon, who was a close follower of Blanqui, wrote a book entitled Du Molochisme juif, in which he also attacked the Jews on anti-religious as well as racial grounds, in addition to using the usual economic terms of disparagement.1 Socialist anti-Semitism, just as non-socialist, can be seen to have three modes of expression: economic, "religious" (actually anti-clerical) and racial, although for the socialists the first two would have a particular meaning in their criticism of capitalism and of religion as the "opium of the people". In elaborating their various critiques of contemporary society these early socialists often used the Jews as a symbol of the rise of capitalism. Whether it was commercial or finance capitalism, the Jewish * I would like to thank M. -

Loughborough Talk, 7 March 2012. Seriality and “Everyone's Place

Loughborough Talk, 7th March 2012. Seriality and “Everyone’s Place Under the Sun”: Proudhon with Kant. Whole Earth, Fragile Planet? …Ainsi le principe d’occupation est abandonné: on ne dit plus : La terre est au premier qui s’en empare…désormais l’on avoue que la terre n’est point le prix de la course ; à moins d’autre empêchement, il y a place pour tout le monde au soleil. Chacun peut attacher sa chèvre à la haie, conduire, sa vache dans la plaine, semer un coin de champ, et faire cuire son pain au feu de son foyer. …Thus, the principle of occupation is abandoned ; no longer is it said : « The land belongs to the one who first seizes it… But henceforth… it will be admitted that the earth is not a prize to be won in a race; in the absence of any other obstacle, there is a place for everyone under the sun. Each one may tie his goat to the hedge, lead his cow to pasture, sow a corner of a field, and bake his bread by his own fireside. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon What is Property? (2009, 215; 2007, 69). …ein Besuchsrecht, welches allen Menschen zusteht, sich zur Gesellschaft anzubieten, vermöge des Rechts des gemeinschaftlichen Besitzes der Oberfläche, auf der, als 1 Kugelfläche, sie sich nicht ins Unendliche zerstreuen können, sondern endlich sich doch neben einander dulden zu können, ursprünglich aber niemand an einem Orte der Erde zu sein mehr Recht hat, als der andere.. ..a right of resort, for all men are entitled to present themselves in the society of others by virtue of their right to communal possession of the earth’s surface. -

Theories About Sex and Sexuality in Utopian Socialism

Journal of Homosexuality ISSN: 0091-8369 (Print) 1540-3602 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wjhm20 Theories About Sex and Sexuality in Utopian Socialism Saskia Poldervaart To cite this article: Saskia Poldervaart (1995) Theories About Sex and Sexuality in Utopian Socialism, Journal of Homosexuality, 29:2-3, 41-68, DOI: 10.1300/J082v29n02_02 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J082v29n02_02 Published online: 18 Oct 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 144 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wjhm20 Download by: [Vanderbilt University Library] Date: 25 October 2017, At: 04:27 Theories About Sex and Sexuality in Utopian Socialism Saskia Poldervaart Universiteit van Amsterdam SUMMARY. It was the utopian socialists of the period 1800-50 (Fourier, Saint-Simon, and the Saint-Simonians in France, as well as the Owenites in Great Britain) who not only challenged the imperial- ism of reason but sought to rehabilitate the flesh by valuing its plea- sure and incentives. Sex and sexuality were central issues for the first socialists, who were scorned as ‘‘utopian’’ by Marx and Engels for seeking to improve the status of all members of society through peaceful means. Because Marxism has played a greater role in the history of socialism, the utopian socialist discussions have been largely disregarded. This essay analyzes the works of the utopian so- cialists Fourier, Saint-Simon, and the Saint-Simonians, arguing that resurgences of the utopian socialist tradition can be discerned around 1900 and again circa 1970. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Kropotkin: Reviewing the Classical Anarchist Tradition

Kropotkin Reviewing the Classical Anarchist Tradition Ruth Kinna © Ruth Kinna, 2016 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 4229 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 1041 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0501 0 (epub) The right of Ruth Kinna to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Part 1 Portrait of the Anarchist as an Old Man 1. Out with the Old, in with the New 9 2. From New Anarchism to Post-anarchism 25 Conclusion to Part 1 45 Part 2 Coming Out of Russia Introduction to Part 2: (A Beautiful White Christ) Coming Out of Russia 49 3. Nihilism 55 4. Mapping the State 79 Conclusion to Part 2 105 Part 3 Revolution and Evolution Introduction to Part 3: The General Idea of Anarchy 119 5. Anarchism: Utopian and Scientifi c 127 6. The Revolution Will Not Be Historicised 155 Conclusion to Part 3 185 Reviewing the Classical Anarchist Tradition 197 Notes 205 Bibliography 237 Index 259 iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Edinburgh University Press (EUP) for supporting this project, particularly James Dale who fi rst talked to me about the book and Nicola Ramsey and Michelle Houston who took the project over. -

Anarchist Social Science : Its Origins and Development

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Anarchist social science : its origins and development. Rochelle Ann Potak University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Potak, Rochelle Ann, "Anarchist social science : its origins and development." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2504. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2504 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANARCHIST SOCIAL SCIENCE: ITS ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis Presented By ROCHELLE ANN POTAK Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the den:ree of MASTER OF ARTS December 1974 Political Science ANARCHIST SOCIAL SCIENCE: ITS ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT A Thesis By ROCHELLE AliN POTAK Approved as to style and content by: Guenther Lewy, Chairman of Committee Dean Albertson, Member — Glen Gordon, Chairman Department of Political Science December 197^ Affectionately dedicated to my friends Men have sought for aees to discover the science of govern- ment; and lo l here it is, that men cease totally to attempt to govern each other at allJ that they learn to know the consequences of their OT-m acts, and that they arrange their relations with each other upon such a basis of science that the disagreeable consequences shall be assumed by the agent himself. Stephen Pearl Andrews V PREFACE The primary purpose of this thesis is to examine anarchist thought from a new perspective. -

The Commonwealth of Bees: on the Impossibility of Justice-Through-Ethos *

THE COMMONWEALTH OF BEES: ON THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF JUSTICE-THROUGH-ETHOS * By Gerald Gaus Abstract: Some understand utopia as an ideal society in which everyone would be thoroughly informed by a moral ethos: all would always act on their pure conscientious judgments about justice, and so it would never be necessary to provide incentives for them to act as justice requires. In this essay I argue that such a society is impossible. A society of purely conscientiously just agents would be unable to achieve real justice. This is the Paradox of Pure Conscientiousness. This paradox, I argue, can only be overcome when individuals are prepared to depart from their own pure, conscientious, judgments of justice. KEY WORDS: ideal theory , egalitarian ethos , incentives , public justice , public reason , social rules It is true, that certain living creatures (as bees, and ants), live sociably one with another, (which are therefore by Aristotle numbered amongst political creatures), and yet have no other direction, than their partic- ular judgements and appetites, nor speech, whereby one of them can signify to another, what he thinks expedient for the common benefit; and therefore some man may perhaps desire to know, why mankind cannot do the same. — Hobbes, Leviathan I . A Harmonious World of Perfectly Just Agents? It is tempting to understand “nonideal” political theory as that which accommodates human frailties such as selfishness or narrow loyalties, while an “ideal” or “utopian” theory is one that depicts a society of per- fect moral agents. 1 In such an ideal society everyone would be thoroughly * My thanks to the other contributors to this volume for their valuable comments and suggestions.