Kropotkin: Reviewing the Classical Anarchist Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Continuum Companion to Anarchism

The Continuum Companion to Anarchism 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd i 6/9/2001 3:18:11 PM The Continuum Companion to Anarchism Edited by Ruth Kinna 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd iii 6/9/2001 3:18:13 PM Continuum International Publishing Group The Tower Building 80 Maiden Lane 11 York Road Suite 704 London SE1 7NX New York, NY 10038 www.continuumbooks.com © Ruth Kinna and Contributors, 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the permission of the publishers. E ISBN: 978-1-4411-4270-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record of this title is available from the Library of Congress. Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems Pvt Ltd, Chennai, India Printed and bound in the United States of America 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd iv 6/9/2001 3:18:13 PM Contents Contributors viii Acknowledgements xiv Part I – Research on Anarchism 1 Introduction 3 Ruth Kinna Part II – Approaches to Anarchist Research 2 Research Methods and Problems: Postanarchism 41 Saul Newman 3 Anarchism and Analytic Philosophy 50 Benjamin Franks 4 Anarchism and Art History: Methodologies of Insurrection 72 Allan Antliff 5 Participant Observation 86 Uri Gordon 6 Anarchy, Anarchism and International Relations 96 Alex Prichard Part III – Current Research in Anarchist Studies 7 Bridging the Gaps: Twentieth-Century Anglo-American Anarchist Thought 111 Carissa Honeywell 8 The Hitchhiker as Theorist: Rethinking Sociology and Anthropology from an Anarchist Perspective 140 Jonathan Purkis 9 Genders and Sexualities in Anarchist Movements 162 Sandra Jeppesen and Holly Nazar v 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd v 6/9/2001 3:18:13 PM Contents 10 Literature and Anarchism 192 David Goodway 11 Anarchism and the Future of Revolution 212 Laurence Davis 12 Social Ecology 233 Andy Price 1 3 Leyendo el anarchismo a través de ojos latinoamericanos : Reading Anarchism through Latin American Eyes 252 Sara C. -

C:\Users\Mark\Documents\RWORKER\Rw Sept-Oct

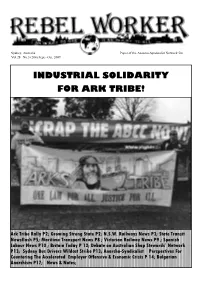

Sydney, Australia Paper of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Network 50c Vol.28 No.3 (204) Sept.- Oct. 2009 INDUSTRIAL SOLIDARITY FOR ARK TRIBE! Ark Tribe Rally P2; Growing Strong State P2; N.S.W. Railways News P3; State Transit Newsflash P5; Maritime Transport News P8 ; Victorian Railway News P9 ; Spanish Labour News P10 ; Britain Today P 12; Debate on Australian Shop Stewards’ Network P13; Sydney Bus Drivers Wildcat Strike P13; Anarcho-Syndicalist Perspectives For Countering The Accelerated Employer Offensive & Economic Crisis P 14; Bulgarian Anarchism P17; News & Notes; 2 Rebel Worker suburbs in Adelaide. 200 people I think, destroying rights for the rest of us. The Rebel Worker is the bi-monthly maybe nearing 300? Judging by us having only time I felt like heckling was “like Paper of the A.S.N. for the propo- given out 50 leaflets to less than a quarter Ned Kelly, he’s been pushed around, gation of anarcho-syndicalism in of the crowd in about 2 minutes.5 political forced to do things he shouldn’t have to..” Australia. forces made an appearance, including the where I was too shy to heckle with “but he greens, democrats, an independent, ‘free still hasn’t shot any cops!” Unless otherwise stated, signed Australia party’(newly formed party of Would have got a laugh or two, especially Articles do not necessarily represent ‘motorcycle enthusiasts’(for anyone inter- from the “motorcycle enthusiasts”. Any- the position of the A.S.N. as a whole. nationally, bikers have been targeted by way.. to my understanding a motion was Any contributions, criticisms, letters absurd state powers recently, and have passed at the ACTU (Australian Council or formed a political party) and Socialist Al- of Trade Unions) (amazingly..) congress, Comments are welcome. -

“The Whole World Is Our Homeland”: Anarchist Antimilitarism

nº 24 - SEPTEMBER 2015 PACIFISTS DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN DEPTH “The whole world is our homeland”: Anarchist antimilitarism Dolors Marín Historian Anarchism as a form of human liberation and as a social, cultural and economic al- ternative is an idea born from the European Illustration. It belongs to the rationalism school of thought that believes in the education of the individual as the essential tool for the transformation of society. The anarchists fight for a future society in which there is no place for the State or authoritarianism, because it is a society structured in small, self-sufficient communities with a deep respect for nature, a concept already present among the utopian socialists. A communitarian (though non necessarily an- ti-individualistic) basis that will be strengthened by the revolutionary trade unionism who uses direct action and insurrectional tactics for its vindications. On a political level, the anarchists make no distinction between goals and methods, because they consider that the fight is in itself a goal. In the anarchist denunciation of the modern state’s authoritarianism the concepts of army and war are logically present. This denunciation was ever-present in the years when workers internationalism appeared, due to the growth of modern European na- tionalisms, the independence of former American colonies and the Asian and African context. The urban proletariat and many labourers from around the world become the cannon fodder in these bloodbaths of youth and devastations of large areas of the pla- net. The workers’ protest is hence channelled through its own growing organizations (trade unions, workmen’s clubs, benefit societies, etc), with the support and the louds- peaker of abundant pacifist literature that will soon be published in clandestine book- lets or pamphlets that circulate on a hand-to-hand basis (1). -

Mother Earth

Vol. IX. December, 1914 JVo> 10 CONTENTS *i Page Special Notice to our New York Friends 305 Observations and Comments L. D. A. 306 The War and the Workers E. L. Pratt 312 Wars and Capitalism Peter Kropotkin 315 My Lectures in New York Emma Goldman 319 Emma Goldman in Chicago Margaret C. Anderson 320 Alfred Marsh I Harry Kelly 325 I San Quentin Rebekah E. Raney 327 A Ferrer Colony I 333 I Anti-Militarist League Fund 335 % Alexander Berkman Dates 33<3 ± Emma Goldman Publisher Alexander Berkman .... Editor Office: 20 East 125th Street, New York City Telephone, Harlem 6194 Price 10 Cents per Copy One Dollar per Year M"H"5"M- •H^^^^^"H"^«"H^H"M^♦•^^H"^^t Mother Earth Special Christmas Offer Dear Friends: You will no doubt purchase some gifts for your friends. Why not combine beauty with purpose? Why not help x, those you care for to see life in a new light, and at the same" 4 time lighten our burdens in the great task of human emanci pation? We have a lot of good and valuable books which we offer jj you at a very low price. Give us your order and the name and address of those you wish to surprise and we will ship, them your choice direct as coming from you. *|J $1.50 set for $1.00 "Anarchism anil Other Essays," by Emma Goldman $1.00 'What Every Mother Should Know," by Margaret Sanger. .50 Postage 15 "* $2.50 set for $2.00 * "Selected Works of Voltairlne de Cley re" $1.00 "The Social Significance of Drama," by Emma •}• Modern * Goldman 1.00 * A Play by August Strindberg 50 A Postage 25 4 $5.00 set for $3.00 A "Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist," by Alexander Berkman. -

9. Notes and Index.Pdf

- NOTE rn NoI NOTES ,i I cccnt .rSarrlst i \ t:t tC. i l. cloes Preface l. J:rnres Joll, The Anarchisls,2nd etl , (C)ambridge, Nlass.: H:rn'artl llnivet'sin Press, 'i:tlike 19tt0), p viii. .r .rl istic: 2 Sinr:e the literature on this oeriod of soci:rlis( ernd cornrnunist intertrationalism is i.rlizccl immense, it is possible to rite onlr solne rcprL\r'ntJti\c titles here Julius BtaLnthal's ()eschir.hte der Internationale, 3 r'oirs (Flarlno\er: Dietz, l96l-1971 I has bccornc standarcl ' lllrl)l\ on a ccnturl of internationalisrn, though the emphasis is alrnostexclusivclr uporr politir:al . )|S [O :rnd not trade union intern:rtionalisrn. IIore sper:ifir:rllr, on the Setoncl Internatioral, sce Jarnes Joll, The Second InternatiormL, 1889-1911. rcr ed. (l-rtrrdon ancl Boston: r.hil)s, Routledge ancl Keean Paul, 197'1). On the International Federation of Trade flnions before ,11( )ln1C the rvar arrd on its post-rvar rerival. see Joh:rnn Sasst:nbach, I'inlundzuanzig Ja.lLre internationaLer Geuterksthaf tsbelDegung (Anrstcr(1arn: IrrtcrrraIionalcn C]cterlschaf tsbun- .Li aucl dcs, 1926), and Lervis Lonvin, Lobor and Inlernatiortalisrn (Ncl York: N'Iacrnillan, 1929). iltloIls, C)n the pcrst-war Labour and Socialist International, see John Ptice, Tlrc Intcrttational Labour Llouernent (London: Oxford l-iniversitl Press 19.15) On the so-callecl Trro-ancl- ;, lile, a-Half Internationzrl, scc Andr6 Donneur, Hi.stoire de I'L'nion des Pttrtis SetciaListes (tour I'Action InternationaLe (Lausanue: fl niversit6 de ClenEve, Institu t l-n ir crsi Lairc dcs FIaLrtes :;r otlet n -L,tudes Internat.ionales, 1967). -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

The Italians and the Iwma

chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. This chapter will also include some brief words on the sociology and geography of Italian Internationalism and a discussion of newer approaches that transcend the rather stale polemics between parti- sans of a Marxist or anarchist reading of Italian Internationalism and incorpo- rates themes that have enlivened the study of the Risorgimento, namely, State responses to the International, the role of transnationalism, romanticism, 1 The best overviews of the iwma in Italy are: Pier Carlo Masini, La Federazione Italiana dell’Associazione Internazionale dei Lavoratori. Atti ufficiali 1871–1880 (atti congressuali; indirizzi, proclaim, manifesti) (Milan, 1966); Pier Carlo Masini, Storia degli Anarchici Ital- iani da Bakunin a Malatesta, (Milan, (1969) 1974); Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism 1864–1892 (Princeton, 1993); Renato Zangheri, Storia del socialismo italiano. -

The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock

Transoceanic Canada: The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock by Matthew Hiebert B.A., The University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A., The University of Amsterdam, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2013 c Matthew Hiebert, 2013 ABSTRACT Through a critical examination of his oeuvre in relation to his transoceanic geographical and intellectual mobility, this dissertation argues that George Woodcock (1912-1995) articulates and applies a normative and methodological approach I term “regional cosmopolitanism.” I trace the development of this philosophy from its germination in London’s thirties and forties, when Woodcock drifted from the poetics of the “Auden generation” towards the anti-imperialism of Mahatma Gandhi and the anarchist aesthetic modernism of Sir Herbert Read. I show how these connected influences—and those also of Mulk Raj Anand, Marie-Louise Berneri, Prince Peter Kropotkin, George Orwell, and French Surrealism—affected Woodcock’s critical engagements via print and radio with the Canadian cultural landscape of the Cold War and its concurrent countercultural long sixties. Woodcock’s dynamic and dialectical understanding of the relationship between literature and society produced a key intervention in the development of Canadian literature and its critical study leading up to the establishment of the Canada Council and the groundbreaking journal Canadian Literature. Through his research and travels in India—where he established relations with the exiled Dalai Lama and major figures of an independent English Indian literature—Woodcock relinquished the universalism of his modernist heritage in practising, as I show, a postcolonial and postmodern situated critical cosmopolitanism that advocates globally relevant regional culture as the interplay of various traditions shaped by specific geographies. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

Social Anarchism. Introduction. Giovanni Baldelli

It was about 1982, two years after the first issue of Social Anarchism was published that I received a call from David Wieck, one of our editorial board members. David, like most of those on the board, had been invited to serve because of his articles which we had reprinted in our first anthology, Reinventing Anarchy. He had become a regular writer for us, and following each issue he would call to let me know what he thought of it. He was a tough taskmaster and was often on target with his comments. This call was different. "Could you use about 1,000 copies of Giovanni Baldelli's Social Anarchism? They'd make great premiums for new subscribers." I had to admit I had never heard of Baldelli and confessed my ignorance to David. "I'll send you a copy. See what you think." When I did receive and read the book, I was impressed by two aspects of Baldelli's work. One was his "moral anarchist philosophy" and the other was the creative manner in which he dealt with economics. So, getting back to David, who it turned out had translated and edited the book, I asked the natural question, "What are you doing with a thousand copies?" As far as I can recall from our conversation, Wieck and Baldelli had submitted the manuscript to Atherton Press of Chicago. It was a moderate-sized academic press, and Social Anarchism fit with their political books series. At some point while the book was being printed, Atherton merged with Aldine and shortly thereafter, the combined publishers declared bankruptcy. -

Sos Political Science & Public Administration M.A.Political Science

Sos Political science & Public administration M.A.Political Science II Sem Political Philosophy:Mordan Political Thought, Theory & contemporary Ideologies(201) UNIT-IV Topic Name-Utopian Socialism What is utopian society? • A utopia is an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its citizens.The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. • Utopia focuses on equality in economics, government and justice, though by no means exclusively, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.According to Lyman Tower SargentSargent argues that utopia's nature is inherently contradictory, because societies are not homogenous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. • The term utopia was created from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America Who started utopian socialism? • Charles Fourier was a French socialist who lived from 1772 until 1837 and is credited with being an early Utopian Socialist similar to Robert Owen. He wrote several works related to his socialist ideas which centered on his main idea for society: small communities based on cooperation Definition of utopian socialism • socialism based on a belief that social ownership of the means of production can be achieved by voluntary and peaceful surrender of their holdings by propertied groups What is the goal of utopian societies? • The aim of a utopian society is to promote the highest quality of living possible. The word 'utopia' was coined by the English philosopher, Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 book, Utopia, which is about a fictional island community. -

A Kurdish-Speaking Community of Change: How Social and Political Organising Takes Shape in the PYD-Controlled Areas in Syria

A Kurdish-Speaking Community of Change: How Social and Political Organising takes Shape in the PYD-controlled Areas in Syria Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts In Middle Eastern Studies Author: Harriet Ida Rump Advisor: Lory Janelle Dance Examiner: Vittorio Felci Date: 11.12.14 Acknowledgements I devote my deepest gratitude to the brave and engaged participants of this research, without their reflections, insights, and generous will to share ideas, this thesis would never have been realised. In the same breath I sincerely thank Lina Myritz for taking the travel with me to Syria, and for inspiring me continuously. I strongly thank my supervisor Lory Dance, she is an inspirational role model with her critical thoughts and writings, which open up for new methods of research. I am particularly appreciative of all the inputs and perspectives from Farhiya Khalid, Mia Sung Kjaergaard, Søren Rafn, Frederik Johannisson, and Mette Lundsfryd, who all have encouraged me with significant comments. A special thank goes to Lasse Sander for carefully proofreading the thesis in high speed. Finally, for the love and support of all my wonderful friends and family, I am truly thankful. 2 Abstract This thesis explores current trends in social and political organising in Northern Syria, an area controlled by the PYD.1 The research is built on discussions between eight participants from the Syrian Kurdish-speaking community living in the areas. While most discourses on Syria and the Kurdish-speaking community have a macro-political focus and produce racialising descriptions of “Kurdishness” in Syria, less attention is granted to bottom-up organising and the plurality of Kurdishness.