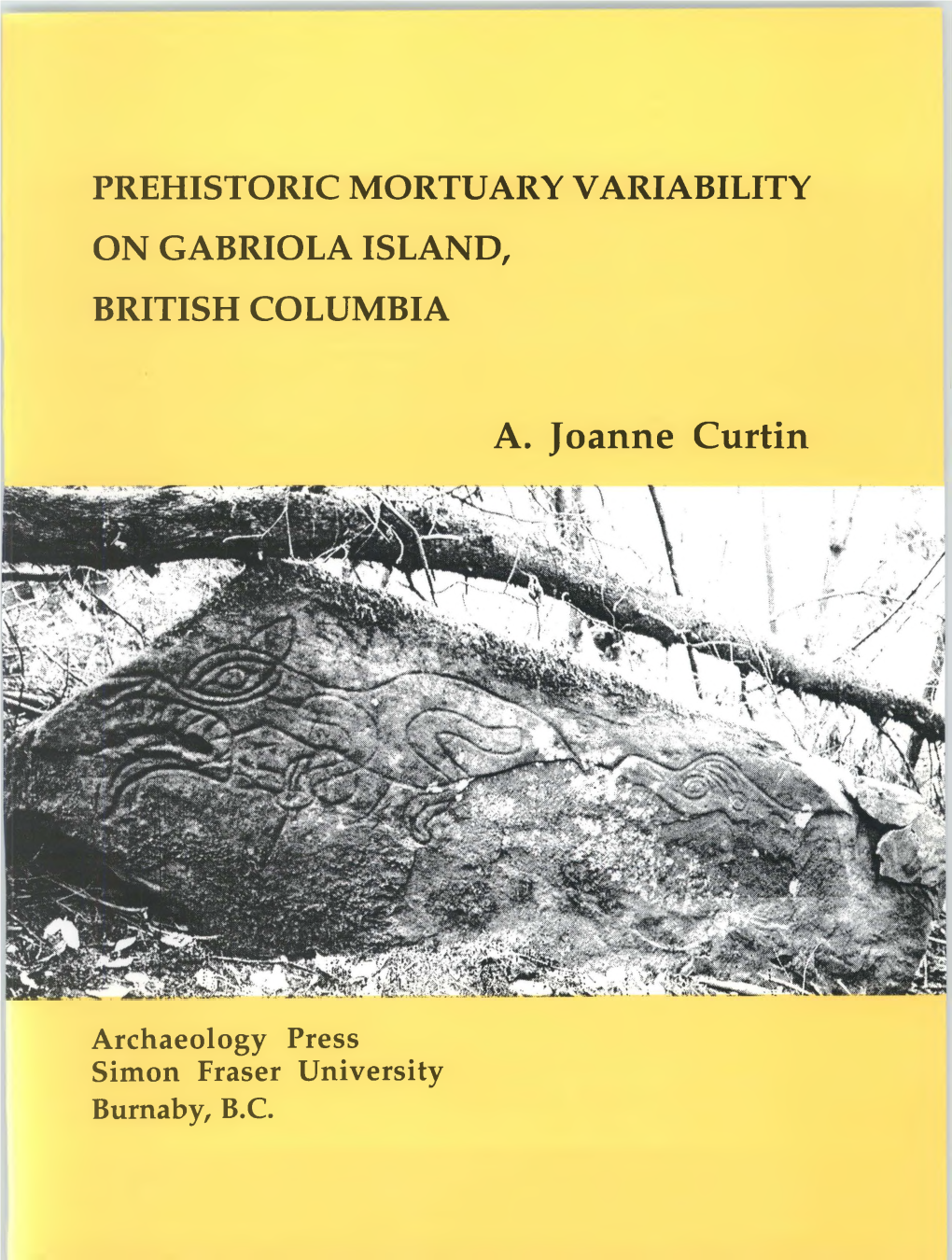

A. Joanne Curtin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARCHEOLOGY of DEATH ANG 6191 (Section 4G20) ANT 4930 (Section 4G21) Fall 2020

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF DEATH ANG 6191 (section 4G20) ANT 4930 (Section 4G21) Fall 2020 Instructor: Dr. James M. Davidson Course Level/Structure: seminar Time: Tuesdays -- periods 6 through 8 (12:50 – 3:50 pm) Classroom: none (online) Office: Turlington B134 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment Website for readings: Canvas Course Description and Objectives: The seminar’s goal is to provide a solid grounding in the anthropological literature of Mortuary studies; that is, data derived from a study of the Death experience. In addition to archaeological data, a strong emphasis will be placed on the theoretical underpinnings of mortuary data, drawn from cultural anthropology and ethnography. Along with more theoretical papers, specific case studies will be used to address a variety of topics and issues, such as Social Organization, Spirituality and Religion, Skeletal Biology (e.g., Paleodemography, Paleopathology, and other issues of Bioarchaeology), Gender Issues, the Ethics of using Human Remains, and Post-Processual Critiques. The time range that we will cover in the course will span from the Neolithic to the 20th century, and numerous cultures from all parts of the globe will be our subject matter. Course Requirements: Class participation/attendance 5% Leading Class Discussion: 5% Synopses (of specific readings) 20% Two essay/reaction papers 20% Major research paper 50% Texts: 1). Chapman, Robert (editor) 1981 The Archaeology of Death. Cambridge University Press. 2). Parker Pearson, Mike 1999 The Archaeology of Death and Burial. Texas A&M University Press. 3). The primary texts will be derived from individual readings (e.g., articles, book chapters) (see website) 1 Attendance: Regular attendance and participation in class discussions is a requirement. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Correlating Biological

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Correlating Biological Relationships, Social Inequality, and Population Movement among Prehistoric California Foragers: Ancient Human DNA Analysis from CA-SCL-38 (Yukisma Site). A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Cara Rachelle Monroe Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Jochim, Chair Professor Lynn Gamble Professor Michael Glassow Adjunct Professor John R. Johnson September 2014 The dissertation of Cara Rachelle Monroe is approved. ____________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble ____________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow ____________________________________________ John R. Johnson ____________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim, Committee Chair September 2014 Correlating Biological Relationships, Social Inequality, and Population Movement among Prehistoric California Foragers: Ancient Human DNA Analysis from CA-SCL-38 (Yukisma Site). Copyright © 2014 by Cara Rahelle Monroe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completing this dissertation has been an intellectual journey filled with difficulties, but ultimately rewarding in unexpected ways. I am leaving graduate school, albeit later than expected, as a more dedicated and experienced scientist who has adopted a four field anthropological research approach. This was not only the result of the mentorships and the education I received from the University of California-Santa Barbara’s Anthropology department, but also from friends -

Curriculum Vitae Brenda J. Baker

CURRICULUM VITAE BRENDA J. BAKER Associate Professor of Anthropology Center for Bioarchaeological Research School of Human Evolution & Social Change Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-2402 Phone: (480) 965-2087; Fax: (480) 965-7671; E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION 1992 Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Dissertation: Collagen Composition in Human Skeletal Remains from the NAX Cemetery (A.D. 350-550) in Lower Nubia. Doctoral committee chair: Dr. George J. Armelagos 1983 M.A. in Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 1981 B.A. in Anthropology, with Honors, Northwestern University Honors thesis: A Bioarchaeological Analysis of N155-2: A Prehistoric Mortuary Structure from Nauvoo, lllinois. Advisor: Dr. Jane E. Buikstra PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2002-present Associate Professor, School of Human Evolution & Social Change (Department of Anthropology prior to 2005), Arizona State University. 1998-2002 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Arizona State University. 1994-1998 Senior Scientist (Bioarchaeology), Curator of Human Osteology and Director of Repatriation Program, Anthropological Survey, New York State Museum, Albany, NY. Developed research program concerning human skeletal remains in the museum's collections and in New York State; consulted on identification of human remains for other agencies (e.g., State Police); supervised staff and student interns in inventory work for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA); oversaw budget and grants for NAGPRA and research projects; served on museum exhibit planning and collections committee; participated in public programming. 1995-1998 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University at Albany, SUNY. 1993-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Moorhead State University, MN. -

THE ARCHEOLOGY of DEATH ANG6191 (Section 7964) Fall 2011

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF DEATH ANG6191 (section 7964) Fall 2011 Instructor: Dr. James M. Davidson Course Level/Structure: Graduate seminar Time: Monday only -- periods 7 through 9 (1:55 pm to 4:55 pm) Class Room: MAT (Matherly Hall), Room 108 Office: Turlington B134 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Wed 1-3 (and by appointment) Website for electronic readings: http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/davidson/courses.htm Course Description and Objectives: The seminar’s goal is to provide a solid grounding in the anthropological literature of Mortuary studies; that is, data derived from a study of the Death Experience. In addition to archaeological data, a strong emphasis will be placed on the theoretical underpinnings of mortuary data, drawn from cultural anthropology and ethnography. Along with more theoretical papers, specific case studies will be used to address a variety of topics and issues, such as Social Organization and Social Structure, Spirituality and Religion, Skeletal Biology (e.g., Paleodemography, Paleopathology, and other issues of Bioarchaeology), Gender Issues, The Ethics of using Human Remains, and Post-Processual Critiques of Mortuary Archaeology. The time range that we will cover in the course will span from the Neolithic to the early 20th century, and numerous cultures from all parts of the globe will be our subject matter. Course Requirements: Class participation/attendance 5% Leading Class Discussion: 5% Synopses (of specific readings) 20% Two essay/reaction papers 20% Major research paper 50% Texts: 1). Chapman, Robert (editor) 1981 The Archaeology of Death. Cambridge University Press. 2). Parker Pearson, Mike 1999 The Archaeology of Death and Burial. -

An Archaeological Investigation of Late Prehistoric and Contact Period Plant Use in the North Carolina Piedmont

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF LATE PREHISTORIC AND CONTACT PERIOD PLANT USE IN THE NORTH CAROLINA PIEDMONT Sierra S. Roark A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: C. Margaret Scarry R.P. Stephen Davis Jr. Anna S. Agbe-Davies Dale L. Hutchinson © 2020 Sierra S. Roark ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Sierra S. Roark: “An Archaeological Investigation of Late Prehistoric and Contact Period Plant Use in the North Carolina Piedmont” (Under the direction of C. Margaret Scarry) The arrival of Europeans to North America spawned instability among Native populations. Past archaeological studies have worked to reconstruct Contact period human- environmental relationships, botanical usage, and subsistence patterns of Native Americans in the North Carolina Piedmont. That research largely emphasizes patterns of continuity regarding resource selection and subsistence patterns. In this study, I incorporate archaeobotanical data from 10 sites excavated across the Dan, Eno, and Haw River drainages and construct a nuanced depiction of Native botanical usage before and after establishing recurring contact with Europeans. My analysis supports previous observations that Native Piedmont groups had similar subsistence practices with observable differences across time and space. Additionally, I propose evidence for intensification in the use of medicinal taxa over time. I argue these lines of evidence demonstrate the maintenance of prehistoric Siouan practices. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a great many debts to those who have helped me with this project. I would like to first thank my gracious advisor and committee. -

Maya Osteobiographies of the Holmul Region, Guatemala

BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Dissertation MAYA OSTEOBIOGRAPHIES OF THE HOLMUL REGION, GUATEMALA: CURATING LIFE HISTORIES THROUGH BIOARCHAEOLOGY AND STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS By AVIVA ANN CORMIER B.A., Brandeis University, 2009 M.A., Boston University, 2015 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 © 2018 by Aviva Ann Cormier All rights reserved Approved by First Reader David M. Carballo, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Archaeology Second Reader Jonathan Bethard, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Anthropology University of South Florida Third Reader Jane E. Buikstra, Ph.D. Regents’ Professor Arizona State University DEDICATION To my family, my mother, and Chad. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this dissertation and this stage of my academic journey would not have been possible without so many individuals and institutions. Thank you to my committee- David Carballo, Mac Marston, Jon Bethard, and Jane Buikstra- for their invaluable guidance and advice. Without their patience, encouragement, and inspiration, this dissertation would not have been possible. David and Mac, thank you for welcoming me as your student and providing me with endless support. Jon, thank you for being my mentor and friend and for teaching me the ways of the Dremel. Thank you, Jane, for introducing me to Kampsville and inspiring me to be a better bioarchaeologist. I also wish to thank Bill Saturno for welcoming me to BU and guiding me through the challenging start of my academic career. Thank you, Francisco Estrada-Belli, for the opportunity to work with the Holmul Archaeological Project and your support of my work both in Guatemala and in Boston. -

THE ARCHEOLOGY of DEATH ANG6191 (Section 10530) ANT4930 (Section 43HG) Spring 2019

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF DEATH ANG6191 (Section 10530) ANT4930 (Section 43HG) Spring 2019 Instructor: Dr. James M. Davidson Course Level/Structure: Graduate seminar Time: Thursday -- periods 2 through 4 (8:30 AM - 11:30 AM) Class Room: Turlington Hall, Room 1208H Office: Turlington B134 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday 2 – 5 pm (and by appointment) Website for electronic readings: http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/davidson/courses.htm Course Description and Objectives: The seminar’s goal is to provide a solid grounding in the anthropological literature of Mortuary studies; that is, data derived from a study of the Death Experience. In addition to archaeological data, a strong emphasis will be placed on the theoretical underpinnings of mortuary data, drawn from cultural anthropology and ethnography. Along with more theoretical papers, specific case studies will be used to address a variety of topics and issues, such as Social Organization and Social Structure, Spirituality and Religion, Skeletal Biology (e.g., Paleodemography, Paleopathology, and other issues of Bioarchaeology), Gender Issues, The Ethics of using Human Remains, and Post-Processual Critiques of Mortuary Archaeology. The time range that we will cover in the course will span from the Neolithic to the 20th century, and numerous cultures from all parts of the globe will be our subject matter. Course Requirements: Class participation/attendance 5% Leading Class Discussion: 5% Synopses (of specific readings) 20% Two essay/reaction papers 20% Major research paper 50% Texts: 1). Chapman, Robert (editor) 1981 The Archaeology of Death. Cambridge University Press. 2). Parker Pearson, Mike 1999 The Archaeology of Death and Burial. -

Virtually Dead: Digital Public Mortuary Archaeology

Virtually Dead: Digital Public Mortuary Archaeology Howard Williams1 and Alison Atkin2 Cite this as: Williams, H. and Atkin, A. 2015 Virtually Dead: Digital Public Mortuary Archaeology, Internet Archaeology 40. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.7.4 1. History and Archaeology Department, University of Chester, UK [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3510-6852 2. Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, UK [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2249-8781 Key words: communication, community archaeology, digital media, digital public archaeology This publication is open access and made possible by the generous support of Manchester Metropolitan University. © Author(s). Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI is given. Summary Over recent decades, the ethics, politics and public engagements of mortuary archaeology have received sustained scrutiny, including how we handle, write about and display the archaeological dead. Yet the burgeoning use of digital media to engage different audiences in the archaeology of death and burial have so far escaped attention. This article explores categories and strategies by which digital media create virtual communities engaging with mortuary archaeology. Considering digital public mortuary archaeology (DPMA) as a distinctive theme linking archaeology, mortality and material culture, we discuss blogs, vlogs and Twitter as case studies to illustrate the variety of strategies by which digital media can promote, educate and engage public audiences with archaeological projects and research relating to death and the dead in the human past. -

Public Archaeology

Public Archaeology Arts of Engagement edited by Howard Williams Caroline Pudney Afnan Ezzeldin Access Archaeology aeopr ch es r s A A y c g c e o l s o s e A a r c Ah Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-373-7 ISBN 978-1-78969-374-4 (e-Pdf) © the individual authors Archaeopress 2019 Cover image: The Heritage Graffiti Project during creation (Photograph: Ryan Eddleston, reproduced with permission) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................................... vii Contributors.......................................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................................x Foreword ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Immigrant Identity in the Indus Civilization: a Multi-Site Isotopic Mortuary Analysis

IMMIGRANT IDENTITY IN THE INDUS CIVILIZATION: A MULTI-SITE ISOTOPIC MORTUARY ANALYSIS By BENJAMIN THOMAS VALENTINE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Benjamin Thomas Valentine 2 To Shannon 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Truly, I have stood on the shoulders of my betters to reach this point in my career. I could never have completed this dissertation without the unfailing support of my family, friends, and colleagues, both at home and abroad. I am grateful, most of all, for my wife, Shannon Chillingworth. I am humbled by the sacrifices she has made for dreams not her own. I can never repay her for the gifts she has given me, nor will she ever call my debt due. Shannon—thank you. I am likewise indebted to the scholars and institutions that have facilitated my graduate research these past eight years. Foremost among them is my faculty advisor, John Krigbaum, who took a chance on me, an aspiring researcher with little anthropological training, and welcomed me into the University of Florida (UF) Bone Chemistry Lab. I have worked hard not to fail him, as he has never failed me. Under John Krigbaum’s mentorship, I have earned my chance to succeed in academe. During my time at UF, I have benefited from the efforts of many excellent faculty members, but I am especially grateful to James Davidson, Department of Anthropology and George Kamenov and Jason Curtis, Department of Geological Sciences. -

University of California, San Diego

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The social implications of ritual behavior in the Maya Lowlands : a perspective from Minanha, Belize Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2488f75d Author Schwake, Sonja Andrea Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Social Implications of Ritual Behavior in the Maya Lowlands: A Perspective from Minanha, Belize. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Sonja Andrea Schwake Committee in charge: Professor Geoffrey E. Braswell, Chair Professor Guillermo Algaze Professor Paul Goldstein Professor Elizabeth Newsome Professor Eric Van Young 2008 Copyright Sonja Andrea Schwake, 2008 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Sonja Andrea Schwake is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my mother, Janja Van Lehn (Janette Schwake). Her endless support, love, and encouragement have helped me on so many occasions and I could not have completed this without her. She -

Forensic and Mortuary Archaeology

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Spring 1-2016 ANTY 413.01: Forensic and Mortuary Archaeology Corey Ragsdale University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ragsdale, Corey, "ANTY 413.01: Forensic and Mortuary Archaeology" (2016). Syllabi. 4626. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/4626 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anthropology 413 Forensic and Mortuary Archaeology Instructor: Dr. Corey Ragsdale Office: Social Sciences 217 Email: [email protected] Office hours: TR 2:00 to 3:30 Course Goals: The primary objective of this course is to familiarize students with field and laboratory procedures used in mortuary and forensic archaeology. In the first portion of the course we will 1) review the literature on mortuary ritual and the theoretical foundations of current approaches; 2) demonstrate the variation in mortuary behavior across cultures, and through time; 3) introduce methods used by archaeologists to generate and interpret mortuary data; and 4) familiarize students with the legal and ethical issues related to mortuary archaeology and the broader issue of repatriation. During the second portion of the course we will apply laboratory and field methods to designated skeletal collections. This portion of the course includes a field recovery exercise, followed by laboratory analyses and reporting.