Previous Learning Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School and College (Key Stage 5)

School and College (Key Stage 5) Performance Tables 2010 oth an West Yorshre FE12 Introduction These tables provide information on the outh and West Yorkshire achievement and attainment of students of sixth-form age in local secondary schools and FE1 further education sector colleges. They also show how these results compare with other Local Authorities covered: schools and colleges in the area and in England Barnsley as a whole. radford The tables list, in alphabetical order and sub- divided by the local authority (LA), the further Calderdale education sector colleges, state funded Doncaster secondary schools and independent schools in the regional area with students of sixth-form irklees age. Special schools that have chosen to be Leeds included are also listed, and a inal section lists any sixth-form centres or consortia that operate otherham in the area. Sheield The Performance Tables website www. Wakeield education.gov.uk/performancetables enables you to sort schools and colleges in ran order under each performance indicator to search for types of schools and download underlying data. Each entry gives information about the attainment of students at the end of study in general and applied A and AS level examinations and equivalent level 3 qualiication (otherwise referred to as the end of ‘Key Stage 5’). The information in these tables only provides part of the picture of the work done in schools and colleges. For example, colleges often provide for a wider range of student needs and include adults as well as young people Local authorities, through their Connexions among their students. The tables should be services, Connexions Direct and Directgov considered alongside other important sources Young People websites will also be an important of information such as Ofsted reports and school source of information and advice for young and college prospectuses. -

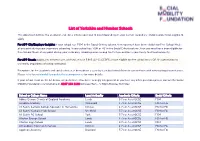

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

'Mistakes' Led to 'Costly and Inefficient' Buildings

Award-winning journalism from the only newspaper dedicated to further education and skills FEWEEK.CO.UK | MONDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2015 | EDITION 126 Page 4 Pages Page 8 Adding value success Inspection 6 & 7 More sfc visits, in the South West results in depth more expected Main picture: Handbridge ‘MISTAKES’ LED TO ‘COSTLY AND and, inset, Ellesmere Port INEFFICIENT’ BUILDINGS One site ‘difficult’ for learners to get to and ‘unsuitable for provision’ £68m developments leave college with huge debts ‘Sell one off’ says commissioner @paulofford it with crippling debt as he called on Skills years after rebuilding it on a site “relatively [email protected] Minister Nick Boles to order that one be difficult to reach by public transport”. sold off. It is also “unsuitable for the provision it Further Education Commissioner Dr David He described the buildings as “costly offers,” according to Dr Collins. Collins has told how a series of blunders and inefficient” — and the college has The building, in Chester, opened around over the “size, location and financing” of revealed plans to shut the Handbridge site, the same time as the college’s Ellesmere these £68m West Cheshire College builds left as recommended by Dr Collins, just four Continues on page 3 FE Week Annual Apprenticeship Conference and Exhibition 2015 THE FLAGSHIP CONFERENCE OF NATIONAL APPRENTICESHIP WEEK DON’T DELAY BOOK TODAY DATE: March 9 to 10, 2015 VENUE: Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, Westminster, London For more information and to register visit feweekaac2015.co.uk 2 @FEWEEK FE WEEK MONDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2015 Edition 126 NEWS FE WEEK News in brief ‘OPEN TRAINEESHIPS UP’ PLEA AS FE loans top 52k FE WEEK team More than 2,300 applications for FE loans STARTS HIT 5K IN FIRST QUARTER in December have taken the total so far this Editor: Chris Henwood year to 52,670. -

YH Regional Tournament Results 2019

Yorkshire & Humber Regional Tournament Results/Qualifiers Badminton Women’s Singles Badminton Men’s Singles Pos Name College Pos Name College 1 John Leggott 1 Bradford Alice Fletcher College Fahd Butt College 2 John Leggott 2 Greenhead Megan Diggle College Anthony Zaho College 3 Emily Wyke 6th 3 Subhaan Bradford Stephenson Form College Ammar College 4 4 Notre Dame Huddersfield Sixth Form Hannah Clarke New College Jai Gata-Aura College 1st 1st Res Res Women’s Basketball Men’s Basketball Pos College Name Pos College Name 1 1 Wyke 6th Form College 2 2 York College 3 3 Cricket – Indoor24 Pos College Name 1 Bradford College 2 New College Pontefract 3 The Sheffield College Cross Country – Women’s Regional Pos Name College 1 Olivia Dyson Greenhead College 2 Zara Tyas Greenhead College 3 Megan Hatfield Wyke 6th Form College 4 Poppy Cooke New College Pontefract 5 Lucie Hall Greenhead College 6 Hannah Lonsdale John Leggott College 7 Penny Tattersfield Wakefield College 8 Sophie Clark John Leggott College 9 Millie Weaver John Leggott College 10 Mia Butler Wakefield College 11 Josie Foster John Leggott College 12 Lydia Throssell Greenhead College 13 14 15 16 Cross Country – Men’s Regional Pos Name College 1 Luke Stonehewer John Leggott College 2 Joe Warren Sheffield College 3 Ben Plumpton Franklin College 4 Dom Harrison John Leggott College 5 Jack Roberts Selby College 6 Harry Brackenridge Huddersfield New College 7 Christian Muneart Scarborough 6th Form 8 Jackson Watts Selby College 9 Xander Cromarky Wyke 6th Form College 10 William King Franklin -

Royal Air Force Visits to Schools

Location Location Name Description Date Location Address/Venue Town/City Postcode NE1 - AFCO Newcas Ferryhill Business and tle Ferryhill Business and Enterprise College Science of our lives. Organised by DEBP 14/07/2016 (RAF) Enterprise College Durham NE1 - AFCO Newcas Dene Community tle School Presentations to Year 10 26/04/2016 (RAF) Dene Community School Peterlee NE1 - AFCO Newcas tle St Benet Biscop School ‘Futures Evening’ aimed at Year 11 and Sixth Form 04/07/2016 (RAF) St Benet Biscop School Bedlington LS1 - Area Hemsworth Arts and Office Community Academy Careers Fair 30/06/2016 Leeds Hemsworth Academy Pontefract LS1 - Area Office Gateways School Activity Day - PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds Gateways School Leeds LS1 - Area Grammar School at Office The Grammar School at Leeds PDT with CCF 09/05/2016 Leeds Leeds Leeds LS1 - Area Queen Ethelburgas Office College Careers Fair 18/04/2016 Leeds Queen Ethelburgas College York NE1 - AFCO Newcas City of Sunderland tle Sunderland College Bede College Careers Fair 20/04/2016 (RAF) Campus Sunderland LS1 - Area Office King James's School PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds King James's School Knareborough LS1 - Area Wickersley School And Office Sports College Careers Fair 27/04/2016 Leeds Wickersley School Rotherham LS1 - Area Office York High School Speed dating events for Year 10 organised by NYBEP 21/07/2016 Leeds York High School York LS1 - Area Caedmon College Office Whitby 4 x Presentation and possible PDT 22/04/2016 Leeds Caedmon College Whitby Whitby LS1 - Area Ermysted's Grammar Office School 2 x Operation -

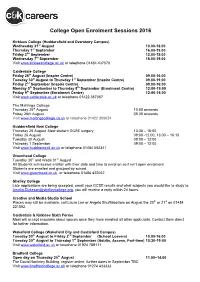

College Open Enrolment Sessions 2016

College Open Enrolment Sessions 2016 Kirklees College (Huddersfield and Dewsbury Campus) Wednesday 31st August 10.00-18.00 Thursday 1st September 16.00-19.00 Friday 2nd September 12.00-15.00 Wednesday 7th September 16.00-19.00 Visit www.kirkleescollege.ac.uk or telephone 01484 437070 Calderdale College Friday 26th August (Inspire Centre) 09.00-16.00 Tuesday 30th August to Thursday 1st September (Inspire Centre) 09.00-19.00 Friday 2nd September (Inspire Centre) 09.00-16:00 Monday 5th September to Thursday 8th September (Enrolment Centre) 12:00-19:00 Friday 9th September (Enrolment Centre) 12:00-16.00 Visit www.calderdale.ac.uk or telephone 01422 357357 The Maltings College Thursday 25th August 10:00 onwards Friday 26th August 08.30 onwards Visit www.maltingscollege.co.uk or telephone 01422 300024 Huddersfield New College Thursday 25 August -New student GCSE surgery 13:30 – 16:00 Friday 26 August 09:00 -12.00, 13:00 – 16:15 Tuesday 30 August 09:00 – 12:00 Thursday 1 September 09:00 – 12:00 Visit www.huddnewcoll.ac.uk or telephone 01484 652341 Greenhead College Tuesday 30th and Weds 31st August All Students will receive a letter with their date and time to enrol on so it isn’t open enrolment Students are enrolled and grouped by school. Visit www.greenhead.ac.uk or telephone 01484 422032 Shelley College Late applications are being accepted, email your GCSE results and what subjects you would like to study to [email protected], you will receive a reply within 24 hours. -

Yorkshire & Humberside Service Report September

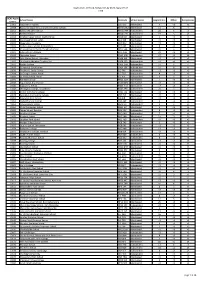

Yorkshire & Humberside Service Report September 2019 1 Yorkshire & Humberside Service Report September 2019 Service Availability The SLA target sets a minimum of 99.7% availability for each customer, averaged over a 12 month rolling period Periods of scheduled and emergency maintenance are discounted when calculating availability of services Monthly and annual availabilities falling below 99.7% are highlighted * Service has resilience - where an organisation retains connectivity during an outage period by means of a second connection, the outage is not counted against its availability figures 12 Month Service Oct 18 Nov 18 Dec 18 Jan 19 Feb 19 Mar 19 Apr 19 May 19 Jun 19 Jul 19 Aug 19 Sep 19 Rolling Availability Askham Bryan College, York Campus 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Barnsley College 100% 100% 99.94% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% >99.99% Barnsley College, Honeywell Lane 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% <12 Months Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council, Personal & 100% 100% 99.94% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% >99.99% Community Development Bishop Burton College, Bishop Burton 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Bradford College 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Bradford College, The David Hockney Building 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Calderdale College 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Calderdale Metropolitan Borough -

Aoc Sport Yorkshire & Humber National Championship Team 2019

AoC Sport Yorkshire & Humber National Championship Team 2019 Badminton Women’s Badminton Men’s Pos College Pos College 1 John Leggott College 1 New College Pontefract 2 Wyke Sixth Form College 2 Thomas Rotherham College 3 Greenhead College 3 New College Pontefract Women’s Basketball Men’s Basketball Pos College Pos College 1 Greenhead College 1 Greenhead College Cricket – Indoor24 Pos College 1 Huddersfield New College Cross Country – Women’s Regional Cross Country – Men’s Regional Pos College Pos College 1 Greenhead College 1 New College Pontefract 2 New College Pontefract 2 Greenhead College 3 Greenhead College 3 John Leggott College 4 John Leggott College 4 Huddersfield New College 5 John Leggott College 5 Thomas Rotherham College 6 New College Pontefract 6 Leeds City College 7 Barnsley College 7 Greenhead College 8 Barnsley College 8 Scarborough 6th Form College AoC Sport Yorkshire & Humber National Championship Team 2019 Women’s 7-a-side football Men’s 7-a-side football Pos College Pos College 1 York College 1 Barnsley College Football for Students with a disability Pos College 1 Shipley College Women’s Golf Men’s Golf Pos College Pos College 1 1 Greenhead College 2 2 North Lindsey College 3 3 Huddersfield New College 4 4 Scarborough Sixth Form College Women’s Hockey Men’s Hockey - Regional Pos College Pos College 1 Greenhead College 1 Franklin College 2 2 Franklin College 3 3 Franklin College 4 4 Franklin College 5 5 Greenhead College 6 6 Greenhead College 7 7 Greenhead College 8 8 Greenhead College 9 9 Greenhead College 10 10 New -

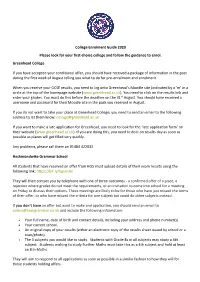

College Enrolment Guide 2020 Please Look for Your First-Choice College and Follow the Guidance to Enrol. Greenhead College If Yo

College Enrolment Guide 2020 Please look for your first-choice college and follow the guidance to enrol. Greenhead College If you have accepted your conditional offer, you should have received a package of information in the post during the first week of August telling you what to do for pre-enrolment and enrolment. When you receive your GCSE results, you need to log onto Greenhead’s Moodle site (indicated by a ‘m’ in a circle at the top of the homepage website (www.greenhead.ac.uk). You need to click on the results link and enter your grades. You must do this before the deadline on the 31st August. You should have received a username and password for their Moodle site in the pack you received in August. If you do not want to take your place at Greenhead College, you need to send an email to the following address to let them know: [email protected] If you want to make a late application for Greenhead, you need to look for the ‘late application form’ on their website (www.greenhead.ac.uk). If you are doing this, you need to do it on results day as soon as possible as places will get filled very quickly. Any problems, please call them on 01484 422032 Heckmondwike Grammar School All students that have received an offer from HGS must upload details of their exam results using the following link: https://bit.ly/hgsenrol They will then contact you by telephone with one of three outcomes - a confirmed offer of a place, a rejection where grades do not meet the requirements, or an invitation to come into school for a meeting on Friday to discuss their options. -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

Catz-The-Year-2010.Pdf

Catz Year 2010_v4 colour change:Catz Year 2007a 28/1/11 11:16 Page c The Year St Catherine’s College . Oxford 2010 Catz Year 2010_v4 colour change:Catz Year 2007a 28/1/11 11:16 Page d Master and Fellows 2010 MASTER RobertALeese, MA (PhD Durh) Marc Lackenby, MA (PhD Camb) Peter P Edwards, MA (BSc, PhD Christoph Reisinger, (Dipl Linz, Professor Roger W Fellow by Special Election in Tutor in Pure Mathematics Salf), FRS Dr phil Heidelberg) Ainsworth, MA, DPhil, FRAeS Mathematics Leathersellers’ Fellow Professor of Inorganic Chemistry Tutor in Mathematics Director of the Smith Institute Professor of Mathematics (Leave M10-T11) FELLOWS Timothy J Bayne, (BA Otago, Sudhir Anand, MA, DPhil Louise L Fawcett, MA, DPhil (BA Marc E Mulholland, MA (BA, Patrick S Grant, MA, DPhil (BEng PhD Arizona) Tutor in Economics Lond) MA, PhD Belf) Nott) FREng Tutor in Philosophy Harold Hindley Fellow Tutor in Politics Wolfson Fellow Cookson Professor of Materials Professor of Quantitative Wilfrid Knapp Fellow Tutor in History Robert E Mabro, CBE, MA (BEng Economic Analysis (Leave M10-T11) Dean Justine N Pila, MA (BA, LLB, PhD Alexandria, MSc Lond) (Leave M10) Melb) Fellow by Special Election Susan C Cooper, MA (BA Collby Gavin Lowe, MA, MSc, DPhil Tutor in Law Richard J Parish, MA, DPhil (BA Maine, PhD California) Tutor in Computer Science College Counsel Kirsten E Shepherd-Barr, MA, Newc) Professor of Experimental Physics Professor of Computer Science DPhil (Grunnfag Oslo, BA Yale) Tutor in French (Leave T11) Bart B van Es, (BA, MPhil, PhD Tutor in English Philip -

Huddersfield

West HUDDERSFIELD Mixed Use Development OFFICE - HOTEL - RETAIL/LEISURE INDICATIVE SCHEME LAYOUT NORTH 01 Trinity West aims to address the need for high quality Huddersfield has Premier League credentials with over commercial and residential space within Huddersfield 23,000 students attending the University of Huddersfield, town centre. The prestigious site commands a premier Kirklees college having some 20,000 students, and the gateway position overlooking the town centre in a highly nearby Greenhead sixth form college being a stone’s throw visible roadside situation. The site extends to 6.1 acres away to the west of the site where a further 2,500 students and has the capacity to accommodate up to 280,000 sq ft attend. The adjacent railway station provides direct links to of the highest quality mixed-use development. Leeds (19 minutes), Manchester (31 minutes) and Liverpool (66 minutes), whilst Trinity West is superbly located on the The site was previously home to The Kirklees College Huddersfield Ring Road some 2 miles including an attractive historic Grade II listed Infirmary from Junction 26 of the M62 motorway. INTRODUCTION building, offering great potential for occupation adding character and interest to the scheme. LEISURE CENTRE HUDDERSFIELD UNIVERSITY BUS STATION TOWN CENTRE GREENHEAD COLLEGE TRAIN STATION A62 (RING ROAD) 02 LOCAL AREA NORTH GREENHEAD PARK GREENHEAD COLLEGE LEISURE CENTRE A62 (RING ROAD) BUS STATION TRAIN STATION TOWN CENTRE 03 NORTH LOCAL AREA ACCOMMODATION SCHEDULE (NET AREAS)* Office Up to 83,604 sq ft 7,767 sq m OFFICE Retail/Leisure Up to 6,006 sq ft 558 sq m Hotel 102 bed 28,901 sq ft 2,685 sq m High specification Grade A offices are available throughout a Food store 23,057 sq ft 2,142 sq m number of buildings.