Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead

Chicago Journal of International Law Volume 13 Number 2 Article 8 1-1-2013 Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead Dale Jamieson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil Recommended Citation Jamieson, Dale (2013) "Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead," Chicago Journal of International Law: Vol. 13: No. 2, Article 8. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol13/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead Dale Jamieson* Abstract In this paperI tell the stoy of the evolution of the climate change regime, locating its origins in "the dream of Rio," which supposed that the nations of the world would join in addressing the interlocking crises of environment and development. I describe the failure at Copenhagen and then go on to discuss the "reboot" of the climate negoiations advocated by Eric A. Posner and David Weisbach. I bring out some ambiguides in their notion of InternationalPareianism, which is supposed to effectively limit the influence of moral ideals in internationalaffairs, and pose a dilemma. I go on to discuss the foundations of their views regarding climate justice, arguing that the most reasonable understandings of their favored theoretical views would not lead to some of their conclusions. Finaly, I return to the climate regime, and make some observations about the road ahead, concluding thatfor theforeseeable future the most important climate change action will be within countries rather than among them. -

Universalist Ethics in Extraterrestrial Encounter Seth D

Universalist Ethics in Extraterrestrial Encounter Seth D. Baum, http://sethbaum.com Department of Geography & Rock Ethics Institute, Pennsylvania State University Published in: Acta Astronautica, 2010, 66(3-4): 617-623 Abstract If humanity encounters an extraterrestrial civilization, or if two extraterrestrial civilizations encounter each other, then the outcome may depend not only on the civilizations’ relative strength to destroy each other but also on what ethics are held by one or both civilizations. This paper explores outcomes of encounter scenarios in which one or both civilizations hold a universalist ethical framework. Several outcomes are possible in such scenarios, ranging from one civilization destroying the other to both civilizations racing to be the first to commit suicide. Thus, attention to the ethics of both humanity and extraterrestrials is warranted in human planning for such an encounter. Additionally, the possibility of such an encounter raises profound questions for contemporary human ethics, even if such an encounter never occurs. Keywords: extraterrestrials, ethics, universalism 1. Introduction To date, humanity has never encountered extraterrestrial life, let alone an extraterrestrial civilization. However, we can also not rule out the possibility that such an encounter will occur. Indeed, insights from the Drake equation (see e.g. [1]) suggest that such an encounter may be likely. As human exploration of space progresses, such an encounter may become increasingly likely. Thus analysis of what would happen in the event of an extraterrestrial encounter is of considerable significance. This analysis is particularly important for the astronautics community to consider given that it is on the leading edge of space exploration. -

Sharing the World with Digital Minds1

Sharing the World with Digital Minds1 (2020). Draft. Version 1.8 Carl Shulman† & Nick Bostrom† [in Clarke, S. & Savulescu, J. (eds.): Rethinking Moral Status (Oxford University Press, forthcoming)] Abstract The minds of biological creatures occupy a small corner of a much larger space of possible minds that could be created once we master the technology of artificial intelligence. Yet many of our moral intuitions and practices are based on assumptions about human nature that need not hold for digital minds. This points to the need for moral reflection as we approach the era of advanced machine intelligence. Here we focus on one set of issues, which arise from the prospect of digital minds with superhumanly strong claims to resources and influence. These could arise from the vast collective benefits that mass-produced digital minds could derive from relatively small amounts of resources. Alternatively, they could arise from individual digital minds with superhuman moral status or ability to benefit from resources. Such beings could contribute immense value to the world, and failing to respect their interests could produce a moral catastrophe, while a naive way of respecting them could be disastrous for humanity. A sensible approach requires reforms of our moral norms and institutions along with advance planning regarding what kinds of digital minds we bring into existence. 1. Introduction Human biological nature imposes many practical limits on what can be done to promote somebody’s welfare. We can only live so long, feel so much joy, have so many children, and benefit so much from additional support and resources. Meanwhile, we require, in order to flourish, that a complex set of physical, psychological, and social conditions be met. -

Care Ethics and Politcal Theory

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi Care Ethics and Political Theory OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi Care Ethics and Political Theory Edited by Daniel Engster and Maurice Hamington 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Oxford University Press 2015 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2015 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015932776 ISBN 978–0–19–871634–1 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

![Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9516/contemporary-moral-theories-introduction-to-contemporary-consequentialism-syllabus-kian-mintz-woo-2419516.webp)

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo] Course Information In this course, I will introduce you to some of the ways that consequentialist thinking leads to surprising or counterintuitive moral conclusions. This means that I will focus on issues which are controversial such as vegetarianism, charity, climate change and health-care. I have tried to select readings that are both contemporary and engaging. Hopefully, these readings will make you think a little differently or give you new ideas to consider or discuss. This course will take place in SR09.53 from 15.15-16.45. I have placed all of the readings for the term (although there might be slight changes), along with questions in green to help guide your reading. Some weeks have a recommended reading as well, which I think will help you to see how people have responded to the kinds of arguments in the required text. Please look over the descriptions and see which readings you are most interested in presenting for class for our first session on 10.03.2016. (Please tell me if you ever find a link that does not work or have any problems accessing content on this Moodle page.) I have a policy that cellphones are off in class; we will have a 5-10 minute break in the course and you can check messages only during the break. As a bonus, I have included at least one fun thing each week which relates to the theme of that week. Marking The course has three marked components: 1. -

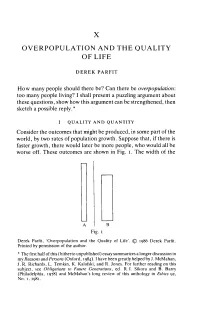

Overpopulation and the Quality of Life’

X OVERPOPULATION AND THE QUALITY OF LI FE DEREK PARFIT How many people should there be? Can there be overpopulation: too many people living? I shall present a puzzling argument about these questions, show how this argument can be strengthened, then sketch a possible reply.* I QUALITY AND QUANTITY Consider the outcomes that might be produced, in some part of the world, by two rates of population growth. Suppose that, if there is faster growth, there would later be more people, who would all be worse off. These outcomes are shown in Fig. i . The width of the Fig. i Derek Parfit, ‘Overpopulation and the Quality of Life’. © 1986 Derek Parfit. Printed by permission of the author. * The first half of this (hitherto unpublished) essay summarizes a longer discussion in my Reasons and Persons (Oxford, 1984). Ihave been greatly helped by J. McMahan, J. R. Richards, L. Temkin, K. Kalafski, and R. Jones. For further reading on this subject, see Obligations to Future Generations, ed. R. I. Sikora and B. Barry (Philadelphia, 1978) and McMahan's long review of this anthology in Ethics 92, No. 1, 1981. 146 DEREK PARFIT blocks shows the number of people living; the height shows how well off these people are. Compared with outcome A, outcome B would have twice as many people, who would all be worse off. To avoid irrelevant complications, I assume that in each outcome there would be no inequality: no one would be worse off than anyone else. I also assume that everyone’s life would be well worth living. -

Overpopulation and the Quality of Life

DEREK PARFIT OVERPOPULATION AND THE QUALITY OF LIFE How many people should there be? Can there be overpopulation: too many people living? I shall present a puzzling argument about these questions, show how this argument can be strengthened, then sketch a possible reply.1 1. QUALITY AND QUANTITY Consider the outcomes that might be produced, in some part of the world, by two rates of population growth. Suppose that, if there is faster growth, there would later be more people, who would all be worse off. These outcomes are shown in Fig. I. A B Fig.1 The width of the blocks shows the number of people living; the height shows how well off these people are. Compared with outcome A, outcome B would have twice as many people, who would all be worse off. To avoid irrelevant complications, I assume that in each outcome there would be no inequality: no one would be worse off than anyone else. I also assume that everyone's life would be well worth living. There are various ways in which, because there would be twice as many people in outcome B, these people might be all worse off than the people in A. There might be worse housing, overcrowded schools, more pollution, less unspoilt 7 J. Ryberg and T. Tännsjö (eds.), The Repugnant Conclusion, 7-22. © 2004 All Rights Reserved. Printed in the Netherlands. 8 D. PARFIT countryside, fewer opportunities, and a smaller share per person of various other kinds of resources. I shall say, for short, that in B there is a lower quality of life. -

Future Generations And

Future Generations and Interpersonal Compensations Moral Aspects of Energy Use by Gustaf Arrhenius and Krister Bykvist Acknowledgements Several people have helped us to write this essay. Our greatest debt is to Wlodek Rabinowicz, who has been an excellent supervisor of the project. He spent a lot of time and energy reading drafts of the essay. Without his painstaking criticism and helpful comments this essay would lack in precision, relevance, and logical correctness. Earlier drafts of the essay were discussed in Sven Danielsson and Wlodek Rabinowicz's seminar at the Department of Philosophy, University of Uppsala. The participants of the seminar contributed with helpful criticisms. Apart from Sven and Wlodek, we would like to thank Thomas Anderberg, Erik Carlson, Tomasz Pol, Peter Ryman, Rysiek Sliwinski, and Jan Österberg. We are especially grateful to Erik Carlson. His critical eye detected many flaws in earlier versions of our theory. A summary of this essay was presented in a seminar at Hässelby Castle, June 1994, organised by NUTEK (Näringsutvecklingsverket), where Bengt Hansson and Lars Ingelstam made interesting comments. Parts of Chapter 3 were presented at Australian National University, Canberra; Monash University, Melbourne; and Queensland University, Brisbane, February 1994. We would especially like to thank Peter Singer and Yew-Kwang Ng for their helpful suggestions. Parts of Chapter 4 were presented at University of Toronto, Department of Philosophy, Toronto, May 1994 and 1995, and at the Learned Society, Canadian Philosophical Association, Montreal, June 1995. We are especially grateful to Danny Goldstick, Tom Hurka, Andrew Latus, Howard Sobel and Wayne Sumner for their valuable comments. Bengt Bykvist, Rebecca Fodden, John Gibson, Wlodek Rabinowicz and Pura Sanchez checked and improved our English. -

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Utilitarianism is the ethical doctrine that the moral worth of an action is solely determined by its contribution to overall utility. It is thus a form of consequentialism, meaning that the moral worth of an action is determined by its outcome—the ends justify the means. Utility — the good to be maximized — has been defined by various thinkers as happiness or pleasure (versus sadness or pain), though preference utilitarians like Peter Singer define it as the satisfaction of preferences. It can be described by the phrase "the greatest good for the greatest number", though the 'greatest number' part gives rise to the problematic mere addition paradox. Utilitarianism can thus be characterized as a quantitative and reductionistic approach to ethics. Utilitarianism can be contrasted with deontological ethics (which focuses on the action itself rather than its consequences) and virtue ethics (which focuses on character), as well as with other varieties of consequentialism. Adherents of these opposing views have extensively criticized the utilitarian view, though utilitarians have been similarly critical of other schools of ethical thought. In general use the term utilitarian often refers to a somewhat narrow economic or pragmatic viewpoint. However, philosophical utilitarianism is much broader than this, for example some approaches to utilitarianism consider non-human animals in addition to people. Contents 1 History 2 Origin of the term 3 Types 3.1 Act vs. rule 3.2 Motive 3.3 Two-level 3.4 Negative 3.5 Average vs. total 3.6 Other species 3.7 Combinations with other ethical schools 4 Biological explanation 5 Criticism and Defense 5.1 Comparing happiness 5.2 Predicting consequences 5.3 Importance of intentions 5.4 Human rights 5.5 Individual interests vs. -

Information to Users

Searching for theory X: A quality-only approach to the problem of future generations. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Merten, Gail. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 19:40:16 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/186375 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Just Better Utilitarianism

Article Just Better Utilitarianism MATTI HÄYRY https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180120000882 . Abstract: Utilitarianism could still be a viable moral and political theory, although an emphasis on justice as distributing burdens and benefits has hidden this from current conversations. The traditional counterexamples prove that we have good grounds for rejecting classical, aggregative forms of consequentialism. A nonaggregative, liberal form of utilitarianism is immune to this rejection. The cost is that it cannot adjudicate when the basic needs of individuals or groups are in conflict. Cases like this must be solved by other methods. This is not a weakness in liberal utilitarianism, on the contrary. The theory clarifies what we should admit to begin with: that ethical doctrines do not have universally acceptable solutions to all difficult problems or hard cases. The theory also reminds us that not all problems are in this sense difficult or cases hard. We could alleviate the plight of nonhuman https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms animals by reducing meat eating. We could mitigate climate change and its detrimental effects by choosing better ways of living. These would imply that most people’s desire satisfaction would be partly frustrated, but liberal utilitarianism holds that this would be justified by the satisfaction of the basic needs of other people and nonhuman animals. Keywords: utilitarianism; consequentialism; liberal utilitarianism; nonhuman animals; climate change The purpose of this article is to remind readers and commentators that utilitarianism could still provide a basis for moral and political choices in bioethics and elsewhere. After a brief historical overview, I will describe where I see that the “justice turn” in normative thinking has left us in terms of views on ethics and social policy. -

Barbara Mackinnon – Utilitarianism and Kant's Moral Theory

Barbara MacKinnon – Utilitarianism and Kant’s Moral Theory Ethical Theory • An ethical theory is a general theory about which actions are right or wrong, and why those actions are right or wrong. An ethical theory will provide criteria for determining whether an action is right or wrong, and it will claim that the action’s meeting those criteria explains why the action is right or wrong. – An ethical theory will entail various particular ethical judgments: for instance, that you have a duty to donate money to charity, that affirmative action is unjust, or that it is impermissible to go to a prostitute. ∗ A particular ethical judgment is just a judgment about what is right or wrong in a particular case. It doesn’t tell us anything about how to behave in other cases. Only an ethical theory will do that. – There are many particular ethical questions that we’re unsure about. We can use our general ethical theory to guide us through these difficult questions. That is, we can use our ethical theory to form particular ethical judgments: Ethical Theory j # Ethical Judgment – However, there are many particular ethical questions that we’re much more confident about. We’re confident, for instance, that torturing babies for fun is pretty much always immoral, that using the elderly for target practice is impermissible, and that enslaving human beings for profit is unjust. We can therefore use judgments like these to test our ethical theories. Ethical Theory " j Ethical Judgment – So there’s a two-way street between our ethical judgments and our ethical theory – we can use the theory to form our judgments, and use our judgments to form the theory.