Arxiv:1712.03079V3 [Cs.CY]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead

Chicago Journal of International Law Volume 13 Number 2 Article 8 1-1-2013 Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead Dale Jamieson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil Recommended Citation Jamieson, Dale (2013) "Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead," Chicago Journal of International Law: Vol. 13: No. 2, Article 8. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol13/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Climate Change, Consequentialism, and the Road Ahead Dale Jamieson* Abstract In this paperI tell the stoy of the evolution of the climate change regime, locating its origins in "the dream of Rio," which supposed that the nations of the world would join in addressing the interlocking crises of environment and development. I describe the failure at Copenhagen and then go on to discuss the "reboot" of the climate negoiations advocated by Eric A. Posner and David Weisbach. I bring out some ambiguides in their notion of InternationalPareianism, which is supposed to effectively limit the influence of moral ideals in internationalaffairs, and pose a dilemma. I go on to discuss the foundations of their views regarding climate justice, arguing that the most reasonable understandings of their favored theoretical views would not lead to some of their conclusions. Finaly, I return to the climate regime, and make some observations about the road ahead, concluding thatfor theforeseeable future the most important climate change action will be within countries rather than among them. -

Universalist Ethics in Extraterrestrial Encounter Seth D

Universalist Ethics in Extraterrestrial Encounter Seth D. Baum, http://sethbaum.com Department of Geography & Rock Ethics Institute, Pennsylvania State University Published in: Acta Astronautica, 2010, 66(3-4): 617-623 Abstract If humanity encounters an extraterrestrial civilization, or if two extraterrestrial civilizations encounter each other, then the outcome may depend not only on the civilizations’ relative strength to destroy each other but also on what ethics are held by one or both civilizations. This paper explores outcomes of encounter scenarios in which one or both civilizations hold a universalist ethical framework. Several outcomes are possible in such scenarios, ranging from one civilization destroying the other to both civilizations racing to be the first to commit suicide. Thus, attention to the ethics of both humanity and extraterrestrials is warranted in human planning for such an encounter. Additionally, the possibility of such an encounter raises profound questions for contemporary human ethics, even if such an encounter never occurs. Keywords: extraterrestrials, ethics, universalism 1. Introduction To date, humanity has never encountered extraterrestrial life, let alone an extraterrestrial civilization. However, we can also not rule out the possibility that such an encounter will occur. Indeed, insights from the Drake equation (see e.g. [1]) suggest that such an encounter may be likely. As human exploration of space progresses, such an encounter may become increasingly likely. Thus analysis of what would happen in the event of an extraterrestrial encounter is of considerable significance. This analysis is particularly important for the astronautics community to consider given that it is on the leading edge of space exploration. -

Generics Analysis Canberra Plan.Pdf

Philosophical Perspectives, 26, Philosophy of Mind, 2012 CONCEPTS, ANALYSIS, GENERICS AND THE CANBERRA PLAN1 Mark Johnston Princeton University Sarah-Jane Leslie2 Princeton University My objection to meanings in the theory of meaning is not that they are abstract or that their identity conditions are obscure, but that they have no demonstrated use.3 —Donald Davidson “Truth and Meaning” From time to time it is said that defenders of conceptual analysis would do well to peruse the best empirically supported psychological theories of concepts, and then tailor their notions of conceptual analysis to those theories of what concepts are.4 As against this, there is an observation — traceable at least as far back to Gottlob Frege’s attack on psychologism in “The Thought” — that might well discourage philosophers from spending a week or two with the empirical psychological literature. The psychological literature is fundamentally concerned with mental representations, with the mental processes of using these in classification, characterization and inference, and with the sub-personal bases of these processes. The problem is that for many philosophers, concepts could not be mental items. (Jerry Fodor is a notable exception, we discuss him below.) We would like to set out this difference of focus in some detail and then propose a sort of translation manual, or at least a crucial translational hint, one which helps in moving between philosophical and psychological treatments of concepts. Then we will consider just how, given the translation, the relevant -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series PHI2014-1077

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: PHI2014-1077 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series PHI2014-1077 An Attempt to Undermine the Extreme Claim Sinem Elkatip Hatipoğlu Assistant Professor of Philosophy İstanbul Şehir University Turkey 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: PHI2014-1077 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Hatipoğlu, S.E., (2014) "An Attempt to Undermine the Extreme Claim”, Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: PHI2014-1077. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. -

Sharing the World with Digital Minds1

Sharing the World with Digital Minds1 (2020). Draft. Version 1.8 Carl Shulman† & Nick Bostrom† [in Clarke, S. & Savulescu, J. (eds.): Rethinking Moral Status (Oxford University Press, forthcoming)] Abstract The minds of biological creatures occupy a small corner of a much larger space of possible minds that could be created once we master the technology of artificial intelligence. Yet many of our moral intuitions and practices are based on assumptions about human nature that need not hold for digital minds. This points to the need for moral reflection as we approach the era of advanced machine intelligence. Here we focus on one set of issues, which arise from the prospect of digital minds with superhumanly strong claims to resources and influence. These could arise from the vast collective benefits that mass-produced digital minds could derive from relatively small amounts of resources. Alternatively, they could arise from individual digital minds with superhuman moral status or ability to benefit from resources. Such beings could contribute immense value to the world, and failing to respect their interests could produce a moral catastrophe, while a naive way of respecting them could be disastrous for humanity. A sensible approach requires reforms of our moral norms and institutions along with advance planning regarding what kinds of digital minds we bring into existence. 1. Introduction Human biological nature imposes many practical limits on what can be done to promote somebody’s welfare. We can only live so long, feel so much joy, have so many children, and benefit so much from additional support and resources. Meanwhile, we require, in order to flourish, that a complex set of physical, psychological, and social conditions be met. -

UTILITARIANISM and PERSONAL IDENTITY 183 © 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers

The Journal of Value Inquiry 33: 183–199, 1999. UTILITARIANISM AND PERSONAL IDENTITY 183 © 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Utilitarianism and Personal Identity DAVID W. SHOEMAKER Department of Philosophy, University of Memphis, 327 Clement Hall, Memphis, TN 38152, USA 1. Introduction Ethical theories must include an account of the concept of a person. They also need a criterion of personal identity over time. This requirement is most needed in theories involving distributions of resources or questions of moral responsibility. For instance, in using ethical theories involving com- pensations of burdens, we must be able to keep track of the identities of persons earlier burdened in order to ensure that they are the same people who now are to receive the compensatory benefits. Similarly, in order to attribute moral responsibility to someone for an act, we must be able to determine that that person is the same person as the person who performed the act. Unfortunately, ethical theories generally include a concept of a person and criteria of personal identity either as notions implied or presupposed by the already worked out theory, with little or no argument given in support of them. But both approaches are unsatisfactory, for each runs the risk of ignoring certain fundamental features of the way persons actually are. What is needed first is a plausible metaphysical account of persons and personal identity to which an ethical theory might then conform and apply. Derek Parfit has attempted to provide such an account in Reasons and Persons, where he argues for what he calls the reductionist view of persons and personal identity and then attempts to show how such a conception provides a metaphysical background that lends important partial support to utilitarianism.1 But Parfit’s metaphysical view is neutral between two possible conceptions of personhood, and utilitarianism presupposes the truth of the more radical of the two conceptions, which precludes the possibility of there being a class of goods crucial to any plausible ethical theory. -

Theories of Personal Identity

Dean Zimmerman Materialism, Dualism, and “Simple” Theories of Personal Identity “Complex” and “Simple” Theories of Personal Identity Derek Parfit introduced “the Complex View” and “the Simple View” as names for contrasting theories about the nature of personal identity. He detects a “reductionist tradition”, typified by Hume and Locke, and continuing in such twentieth‐century philosophers as Grice, Ayer, Quinton, Mackie, John Perry, David Lewis, and Parfit himself. According to the Reductionists, “the fact of personal identity over time just consists in the holding of certain other facts. It consists in various kinds of psychological continuity, of memory, character, intention, and the like, which in turn rest upon bodily continuity.” The Complex View comprises “[t]he central claims of the reductionist tradition” (Parfit 1982, p. 227). The Complex View about the nature of personal identity is a forerunner to what he later calls “Reductionism”. A Reductionist is anyone who believes (1) that the fact of a person’s identity over time just consists in the holding of certain more particular facts, and (2) that these facts can be described without either presupposing the identity of this person, or explicitly claiming that the experiences in this person’s life are had by this person, or even explicitly claiming that this person exists. (Parfit 1984, p. 210) Take the fact that someone remembers that she, herself, witnessed a certain event at an earlier time. When described in those terms, it “presupposes” or “explicitly claims” that the same person is involved in both the episode of witnessing and of remembering. Purging the psychological facts of all those that 1 immediately imply the cross‐temporal identity of a person will leave plenty of grist for the mills of psychological theories of persistence conditions. -

Survival by Redescription: Parfit on Consolation and Death

Survival by Redescription: Parfit on Consolation and Death Patrik Hummel Friedrich-Alexander University, Erlangen-Nürnberg Abstract Parfit argues that if we come to believe his theory of personal identity, we should care differently about the future. Amongst others, we can redescribe death in ways that make it seem less bad. I consider three challenges to his reasoning. First, according to the Argument from Above, a fact, event, or state of affairs can be good or bad independently of the value or disvalue of its constituents. Death could thus be bad even if R-relatedness matters and some degree of it is gets pre- served. Second, I argue that the Extreme Claim and the Moderate Claim suggest that it is unclear whether what we are left with in Parfit’s picture is less bad than death. Third, I propose that in light of the foregoing, we might still regard Parfit’s redescription and its suggested effects on our concern as rationally permissible. However, I claim that rational permissibility does not fully deliver upon the promise that the redescription is also consoling. Despite these challenges, I con- clude that Parfit has given us valuable prompts for reconsidering our attitudes to- wards death. He has set an inspiring example for how philosophical arguments can show us new ways of thinking about ourselves and our practical concerns. Keywords: Parfit, Death, Concern, Personal identity, Rationality. 1. Introduction Parfit argues that if we come to believe his theory of personal identity, we should care differently about the future. Amongst others, we can redescribe death in ways that make it seem less bad. -

Care Ethics and Politcal Theory

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi Care Ethics and Political Theory OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi Care Ethics and Political Theory Edited by Daniel Engster and Maurice Hamington 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 23/6/2015, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Oxford University Press 2015 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2015 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015932776 ISBN 978–0–19–871634–1 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

![Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9516/contemporary-moral-theories-introduction-to-contemporary-consequentialism-syllabus-kian-mintz-woo-2419516.webp)

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo] Course Information In this course, I will introduce you to some of the ways that consequentialist thinking leads to surprising or counterintuitive moral conclusions. This means that I will focus on issues which are controversial such as vegetarianism, charity, climate change and health-care. I have tried to select readings that are both contemporary and engaging. Hopefully, these readings will make you think a little differently or give you new ideas to consider or discuss. This course will take place in SR09.53 from 15.15-16.45. I have placed all of the readings for the term (although there might be slight changes), along with questions in green to help guide your reading. Some weeks have a recommended reading as well, which I think will help you to see how people have responded to the kinds of arguments in the required text. Please look over the descriptions and see which readings you are most interested in presenting for class for our first session on 10.03.2016. (Please tell me if you ever find a link that does not work or have any problems accessing content on this Moodle page.) I have a policy that cellphones are off in class; we will have a 5-10 minute break in the course and you can check messages only during the break. As a bonus, I have included at least one fun thing each week which relates to the theme of that week. Marking The course has three marked components: 1. -

Philosophy of Mind Contents

w 页码,1/177(W) Philosophy of Mind Jaegwon Kim BROWN UNIVERSITY Westview Press A Subsidiary of Perseus Books, L.L.C. -v- Dimensions of Philosophy Series All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 1998 by Westview Press, Inc., A subsidiary of Perseus Books, L.L.C. Published in 1996 in the United States of America by Westview Press, Inc., 5500 Central Avenue, Boulder, Colorado 80301-2877, and in the United Kingdom by Westview Press, 12 Hid's Copse Road, Cumnor Hill, Oxford OX2 9JJ A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8133-0775-9; ISBN 0-8133-0776-7 (pbk.) The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984. 10 9 8 -vi- Contents Preface xi 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Minds as Souls: Mental Substances , 2 Mental Properties, Events, and Processes , 5 Philosophy of Mind , 7 Supervenience, Dependence, and Minimal Physicalism , 9 Varieties of Mental Phenomena , 13 Is There a "Mark of the Mental"? 15 Further Readings , 23 Notes , 24 2 MIND AS BEHAVIOR: BEHAVIORISM 25 Reactions Against the Cartesian Conception , 26 What Is Behavior? 28 Logical Behaviorism: Hempel's Argument , 29 A Behavioral Translation of "Paul Has a Toothache," 31 Difficulties -

Overpopulation and the Quality of Life’

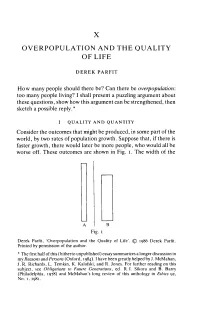

X OVERPOPULATION AND THE QUALITY OF LI FE DEREK PARFIT How many people should there be? Can there be overpopulation: too many people living? I shall present a puzzling argument about these questions, show how this argument can be strengthened, then sketch a possible reply.* I QUALITY AND QUANTITY Consider the outcomes that might be produced, in some part of the world, by two rates of population growth. Suppose that, if there is faster growth, there would later be more people, who would all be worse off. These outcomes are shown in Fig. i . The width of the Fig. i Derek Parfit, ‘Overpopulation and the Quality of Life’. © 1986 Derek Parfit. Printed by permission of the author. * The first half of this (hitherto unpublished) essay summarizes a longer discussion in my Reasons and Persons (Oxford, 1984). Ihave been greatly helped by J. McMahan, J. R. Richards, L. Temkin, K. Kalafski, and R. Jones. For further reading on this subject, see Obligations to Future Generations, ed. R. I. Sikora and B. Barry (Philadelphia, 1978) and McMahan's long review of this anthology in Ethics 92, No. 1, 1981. 146 DEREK PARFIT blocks shows the number of people living; the height shows how well off these people are. Compared with outcome A, outcome B would have twice as many people, who would all be worse off. To avoid irrelevant complications, I assume that in each outcome there would be no inequality: no one would be worse off than anyone else. I also assume that everyone’s life would be well worth living.