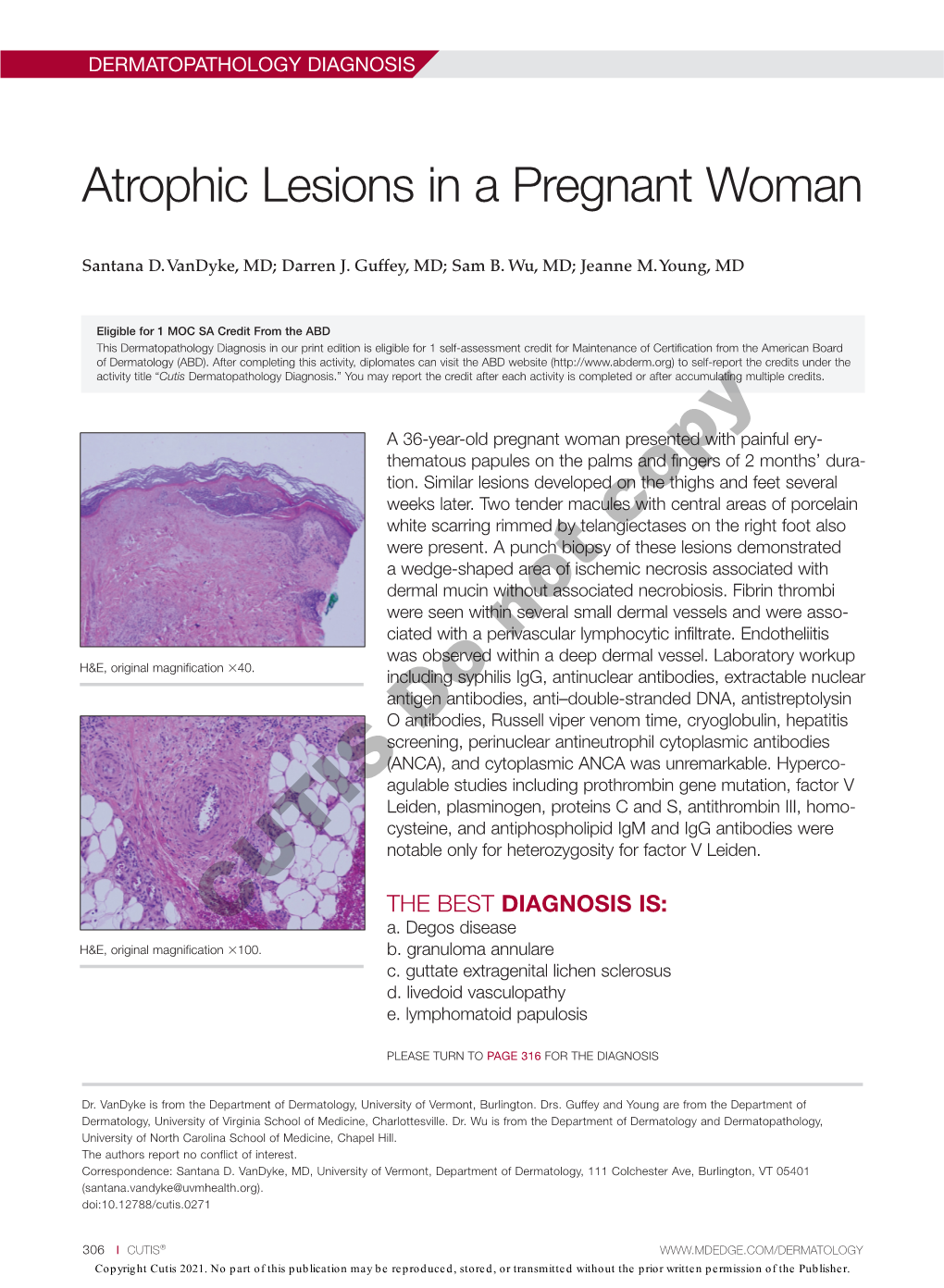

Atrophic Lesions in a Pregnant Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Cutaneous Patterns Are Often the Only Clue to a a R T I C L E Complex Underlying Vascular Pathology

pp11 - 46 ABstract Review Cutaneous patterns are often the only clue to a A R T I C L E complex underlying vascular pathology. Reticulate pattern is probably one of the most important DERMATOLOGICAL dermatological signs of venous or arterial pathology involving the cutaneous microvasculature and its MANIFESTATIONS OF VENOUS presence may be the only sign of an important underlying pathology. Vascular malformations such DISEASE. PART II: Reticulate as cutis marmorata congenita telangiectasia, benign forms of livedo reticularis, and sinister conditions eruptions such as Sneddon’s syndrome can all present with a reticulate eruption. The literature dealing with this KUROSH PARSI MBBS, MSc (Med), FACP, FACD subject is confusing and full of inaccuracies. Terms Departments of Dermatology, St. Vincent’s Hospital & such as livedo reticularis, livedo racemosa, cutis Sydney Children’s Hospital, Sydney, Australia marmorata and retiform purpura have all been used to describe the same or entirely different conditions. To our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews of reticulate eruptions in the medical Introduction literature. he reticulate pattern is probably one of the most This article is the second in a series of papers important dermatological signs that signifies the describing the dermatological manifestations of involvement of the underlying vascular networks venous disease. Given the wide scope of phlebology T and its overlap with many other specialties, this review and the cutaneous vasculature. It is seen in benign forms was divided into multiple instalments. We dedicated of livedo reticularis and in more sinister conditions such this instalment to demystifying the reticulate as Sneddon’s syndrome. There is considerable confusion pattern. -

Lesions Resembling Malignant Atrophic Papulosis in a Patient with Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

Lesions Resembling Malignant Atrophic Papulosis in a Patient With Progressive Systemic Sclerosis Clive M. Liu, MD; Ronald M. Harris, MD, MBA; C. David Hansen, MD Malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP), or Degos bleeding, and neurologic deficits. The prognosis is syndrome, is a rare disorder of unknown etiology. usually poor. Histologic characteristics include a It is characterized by a deep subcutaneous vas- vasculopathy below the necrobiotic zone with culopathy resulting in atrophic, porcelain-white endothelial swelling, proliferation, and thrombosis. papules. We report the case of a 42-year-old To our knowledge, only a few cases of MAP associ- woman with a history of progressive systemic ated with connective tissue disease have been sclerosis who presented with painful subcuta- reported: 4 cases with systemic lupus erythematosus, neous nodules on her abdomen along with 1 with dermatomyositis, and 1 with progressive sys- chronic atrophic papules on her upper and lower temic sclerosis.2-5 We present the case report of a limbs. Biopsy results of both types of lesions woman with progressive systemic sclerosis and revealed vascular thrombi without surrounding MAP-like lesions. inflammation. We briefly review the literature on MAP and its association with various connective Case Report tissue diseases. To our knowledge, there have Round erosions with dry central crusts developed on been no previous reports of a patient with the a 42-year-old woman with a long history of progres- clinical and histologic presentations described sive systemic sclerosis, significant pulmonary hyper- here. Although the histologic appearance of the tension, and right heart failure. Although the subcutaneous nodules was very similar to that of lesions were scattered on all limbs, the most promi- the atrophic papules, the clinical characteristics nent lesions extended from the right labium majus of the 2 types of lesions were strikingly different. -

Degos-Like Lesions Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Degos-Like Lesions Associated with SLE pISSN 1013-9087ㆍeISSN 2005-3894 Ann Dermatol Vol. 29, No. 2, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2017.29.2.215 CASE REPORT Degos-Like Lesions Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Min Soo Jang, Jong Bin Park, Myeong Hyeon Yang, Ji Yun Jang, Joon Hee Kim, Kang Hoon Lee, Geun Tae Kim1, Hyun Hwangbo, Kee Suck Suh Departments of Dermatology and 1Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea Degos disease, also referred to as malignant atrophic pap- 29(2) 215∼218, 2017) ulosis, was first described in 1941 by Köhlmeier and was in- dependently described by Degos in 1942. Degos disease is -Keywords- characterized by diffuse, papular skin eruptions with porce- Degos disease, Degos-like lesions, Systemic lupus eryth- lain-white centers and slightly raised erythematous te- ematosus langiectatic rims associated with bowel infarction. Although the etiology of Degos disease is unknown, autoimmune dis- eases, coagulation disorders, and vasculitis have all been INTRODUCTION considered as underlying pathogenic mechanisms. Approx- imately 15% of Degos disease have a benign course limited Degos disease is a rare systemic vaso-occlusive disorder. to the skin and no history of gastrointestinal or central nerv- Degos-like lesions associated with systemic lupus eryth- ous system (CNS) involvement. A 29-year-old female with ematosus (SLE) are a type of vasculopathy. Almost all history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with Degos-like lesions have the clinical pathognomonic ap- a 2-year history of asymptomatic lesions on the dorsum of all pearance of porcelain-white, atrophic papules with pe- fingers and both knees. -

Degos Disease Associated with Behçet's Disease

Letter to the Editor http://dx.doi.org/10.5021/ad.2015.27.2.235 Degos Disease Associated with Behçet’s Disease Young Jee Kim, Sook Jung Yun, Seung-Chul Lee, Jee-Bum Lee Department of Dermatology, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea Dear Editor: found as an apparent idiopathic disease or as a surrogate Degos disease (DD) is a rare, thrombo-occlusive vasculop- clinical finding in some connective tissue diseases. Here, athy that primarily affect the skin, gastrointestinal tract, we report a patient with cutaneous manifestation of DD, and central nervous system1. The cutaneous lesions pres- associated with mucocutaneous and systemic BD lesions. ent as characteristic papules with porcelain-white central A 45-year-old woman had asymptomatic erythematous atrophy and an erythematous raised border. Behçet’s dis- papules with central, porcelain-white colored umbilication ease (BD) is a systemic vasculitis characterized clinically on the trunk and both extremities for 20 years, and some by recurrent oral aphthous and genital ulcers, cutaneous of the lesions had healed to leave atrophic scars (Fig. 1A, lesions, and iridocyclitis/posterior uveitis2. DD can be B). She also had recurrent oral and genital ulcers for 20 Fig. 1. (A, B) Erythematous to brownish papules with porcelain- white central atrophy. (C) Recurrent oral aphthous ulcer. Received March 13, 2014, Revised May 14, 2014, Accepted for publication June 23, 2014 Corresponding author: Jee-Bum Lee, Department of Dermatology, Chonnam National University Hospital, 42 Jebong-ro, Dong-gu, Gwangju 501-757, Korea. Tel: 82-62-220-6684, Fax: 82-62-222-4058, E-mail: [email protected] This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro- vided the original work is properly cited. -

Expanding Medical Advisory Board Dr. Lee Shapiro, Chief Medical

Awareness. Diagnosis. Education. Research. Our mission is to support and promote research toward treatment and cure of Scleroderma, Degos Disease, and other related disorders, to promote awareness and understanding of these disorders, especially among health-care professionals, and to encourage collaborative efforts, nationally and internationally, aimed at realizing these goals. Expanding Medical Advisory Board Dr. Lee Shapiro, Chief Medical Thank you to all who attended our Officer of the Steffens Foundation, has forged strong Cruise for a Real Cure! collaborative relationships with Scleroderma and Degos More than 100 people took a ride along Disease experts nationally and internationally. He the Hudson River on the Dutch Apple to recently invited 3 physicians and a medical ethicist, who raise awareness and funding for are prestigious experts in their fields, to join Steffens as Scleroderma and Degos Disease members of the medical advisory board for the research and education. foundation. They all graciously agreed to join Steffens in our mission. It is with great pleasure, we introduce Dr. Lesley Saketkoo, Dr. Leslie Frech, Dr. Patrick Whelan, and Stephen Veit, medical ethicist. Dr. Lesley A Saketkoo, MD, MPH, is a researcher, educator and clinician in scleroderma/systemic sclerosis, sarcoidosis, myositis, pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease. In 2011, she established the Scleroderma and Sarcoidosis Patient Care and Research Center between Tulane and Louisiana State University, “center of excellence” by the European Scleroderma Trials and Research Group (EUSTAR), the Thank you to all who donated to make Scleroderma Foundation, and the Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium (SCTC).; the event a success! and also established the Pulmonary Hypertension clinic program at LSU, which is Dutch Apple Cruises & Tours now the LSU-Tulane collaborative Comprehensive Pulmonary Hypertension Center DeMarco’s Italian-American Restaurant (CPHC) at University Medical Center, a Pulmonary Hypertension Association Ellms Family Farms certified center of excellence. -

1 Introduction 1

1 Introduction 1 Part I The Mechanisms of Cutaneous Mosaicism 2 Mosaicism as a Biological Concept 5 2.1 Historical Beginnings 5 2.2 Mosaicism in Plants 6 2.3 Mosaicism in Animals 7 2.4 Mosaicism in Human Skin 9 2.5 Mosaicism Versus Chimerism 10 References 11 3 Two Major Categories of Mosaicism 13 3.1 Genomic Mosaicism 13 3.1.1 Genomic Mosaicism of Autosomes 13 3.1.2 Genomic X-Chromosome Mosaicism in Male Patients 24 3.1.3 Superimposed Segmental Manifestation of Polygenic Skin Disorders 24 3.2 Epigenetic Mosaicism 26 3.2.1 Epigenetic Mosaicism of Autosomal Genes 26 3.2.2 Epigenetic Mosaicism of X Chromosomes 27 References 31 4 Relationship Between Hypomorphic Alleles and Mosaicism of Lethal Mutations 39 References 41 Part II The Patterns of Cutaneous Mosaicism 5 Six Archetypical Patterns 45 5.1 Lines of Blaschko 45 5.1.1 Lines of Blaschko, Narrow Bands 52 5.1.2 Lines of Blaschko, Broad Bands 52 5.1.3 Analogy of Blaschko's Lines in Other Organs. ... 53 5.1.4 Blaschko's Lines in Animals 54 5.1.5 Analogy of Blaschko's Lines in the Murine Brain. 54 http://d-nb.info/1034513591 X 5.2 Checkerboard Pattern 56 5.3 Phylloid Pattern 57 5.4 Large Patches Without Midline Separation 57 5.5 Lateralization Pattern 57 5.6 Sash-Like Pattern 58 References 59 6 Less Well Defined or So Far Unclassifiable Patterns 63 6.1 The Pallister-Killian Pattern 63 6.2 The Mesotropic Facial Pattern 64 References 65 Part III Mosaic Skin Disorders 7 Nevi 69 7.1 The Theory of Lethal Genes Surviving by Mosaicism 70 7.2 Pigmentary Nevi 70 7.2.1 Melanocytic Nevi 70 7.2.2 Other Nevi Reflecting Pigmentary Mosaicism. -

Rare Causes of Stroke

Joint Annual Meeting SNG|SSN Basel, October 10th, 2012 Rare Causes of Stroke PD Dr Patrik Michel Neurology Service, CHUV Unité Cérébrovasculaire How rare are « rare » ischemic strokes ? N=2612 consecutive acute strokes 2003-2011 Rare causes PFO Missing data 4% Dissections 3% 3% 5% Cardioembolic Multiple 5% 30% Lacunar 13% 10% 13% 14% Atherosclerosis stenosis) Unknown «Likely athero» Modified TOAST classification, standardized workup Source: Michel & Eskandari, unpublished Rare stroke syndromes Overview 1. Vasculitis 2. Hypercoagulability and oncologic 3. Drug related stroke 4. Migraine, vasospasms, pregancy 5. Rare cardiac causes 6. Genetic diseases 7. Other non-inflammatory vasculopathies 8. Unusual causes of ICH Primary systemic vasculitides Giant cell ¾ Temporal arteritis ¾ 7DND\DVX¶V arteritis Necrotizing ¾ Polyarteritis nodosa ¾ Churg-Strauss syndrome Granulomatous ¾ :HJHQHU¶V granulomatosis ¾ Lymphomatoid granulomatosis With prominent eye involvement ¾ 6XVDF¶V syndrome ¾ &RJDQ¶V syndrome (also necrotizing) ¾ Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH) ¾ Eales¶UHWLQRSDWK\ ¾ Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy Quiz : 76 y.o. man 'RHVQ¶W see the doctor Now : acute pure left hemiparesis NIHSS fluctuating between 8 and 1 CT/CT-perfusion : normal Diagnosis: lacunar warning syndrome Æ Hyperacute CT: normal Æ IV thrombolysis at 2h25min. Acute CT-angiography : IPP2819339 76 yo man, lacunar warning syndrome Pre-thrombolysis CTA 2819339 Segmental narrowing both vertebrals CTA: A. Fumeaux Duplex and temporal arteritis -

Degos Disease (Malignant Atrophic Papulosis) with Granular Igm on Direct Immunofluorescence

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.12677 Degos Disease (Malignant Atrophic Papulosis) With Granular IgM on Direct Immunofluorescence Tatsiana Pukhalskaya 1 , Julia Stiegler 2 , Glynis Scott 3 , Christopher T. Richardson 2 , Bruce Smoller 4 1. Pathology, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, USA 2. Dermatology, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, USA 3. Dermatopathology, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, USA 4. Pathology and Dermatology, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, USA Corresponding author: Tatsiana Pukhalskaya, [email protected] Abstract Degos disease is a rare vasculopathy characterized by skin papules with central porcelain white atrophy and a surrounding telangiectatic rim. Etiology of this condition is unknown. There are benign and systemic forms of the disease, and the latter may lead to fatality. Connective tissue diseases with Degos-like features have been described, and many authors speculate that Degos is not a specific entity but, rather, a distinctive pattern of disease that is the common endpoint of a variety of vascular insults. We describe the case of a 45-year-old female who presented with numerous red papules with sclerotic white centers and minimal systemic symptoms. Laboratory workup was notable for a negative autoimmune panel and hypercoagulation panel. Histopathology revealed epidermal atrophy, abundant dermal mucin, a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, interface inflammation, papillary dermal hemorrhage, and several small thrombi in the mid-to-superficial vessels. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed strong granular immunoglobulin M (IgM) deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction. Based on the pathognomonic skin findings, persistently negative antinuclear antibody, lack of systemic signs of systemic lupus erythematosus, and characteristic hematoxylin and eosin findings, a diagnosis of Degos disease was rendered. -

Degos' Disease Mimicking Vasculitis

Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Care & Research) Vol. 51, No. 3, June 15, 2004, pp 498–500 DOI 10.1002/art.20393 © 2004, American College of Rheumatology TRAINEE ROUNDS Degos’ Disease Mimicking Vasculitis SOSA V. KOCHERIL, MILA BLAIVAS, BRENT E. APPLETON, WILLIAM J. MCCUNE, AND ROBERT W. IKE Introduction ogy showed severe necrotizing enteritis with interstitial Degos’ disease is a rare disorder with multisystem involve- hemorrhage, possibly ischemic, and acute serositis. Mul- ment and unknown etiology. This entity was first de- tiple vessels with thrombosis were seen, but inflammation scribed by Degos in 1942 (1,2). Other synonyms for this was rare, and suggested the possibility of vasculitis. Cy- disease are malignant atrophic papulosis, atrophic papu- clophosphamide and methylprednisolone were adminis- losquamous dermatitis, fatal cutaneous-intestinal syn- tered for presumed vasculitis. Infliximab therapy was also drome, and thromboangiitis cutaneointestinalis dissemi- initiated. Enoxaparin was initiated due to concern of mes- nata (3). It has been more commonly reported in whites, enteric thrombosis. The patient subsequently underwent men, and those in the third decade of life, although onset revisions of the enterostomies. The biopsies and skin le- age ranges from 3 weeks to 67 years (4). The average course sions were then found to be consistent with Degos’ disease of the disease is reported to be around 2 years (1), but case (Figure 1) and immunosuppressants were discontinued. reports of patients with a benign variant have been re- She was then transferred to our institution for manage- ported with survival of ϳ14 years (5). Death is most com- ment in October 2000. monly due to intestinal perforation or cerebral infarction. -

Thrombophilia: the Dermatological Clinical Spectrum

Global Dermatology Review Article ISSN: 2056-7863 Thrombophilia: the dermatological clinical spectrum Paulo Ricardo Criado1*, Gleison Vieira Duarte2, Lidia Salles Magalhães2 and Jozélio Freire de Carvalho2 1Department of Dermatology, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil 2Rheumatology, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil Abstract The aim of this article is to review the hypercoagulable states (thrombophilia) most commonly encountered by dermatologists, as well as their cutaneous signs, including livedo racemosa, cutaneous necrosis, digital ischemia and ulcerations, reticulated purpura, leg ulcers, and other skin conditions. Recognizing these cutaneous signs is the first step to proper treatment. Our aim is to describe which tests are indicated, and when, in these clinical settings. Introduction Hereditary thrombophilia can be classified into three large groups according to the pathogenic mechanism [1]: The possible causes of vascular occlusion can be divided into three large groups: (i) abnormalities of the vascular wall, (ii) changes in blood (i) Reduction of anticoagulant capacity: There are two systems flow, and (iii) hypercoagulation of the blood [1]. The term thrombophilia capable of blocking the clotting cascade and preventing the was introduced in 1965 by Egeberg [2] and is currently used to describe development of a massive and uncontrollable thrombosis: conditions resulting from hereditary (or primary) and/or acquired natural anticoagulants (antithrombin III, protein C, and hyper-coagulation of the blood that increase the predisposition to protein S) and fibrinolysis (plasminogen-plasmin system). A thromboembolic events [3]. Various risk factors, whether genetic or congenital deficit in any one of these components constitutes acquired, make up the pathogenesis of thrombosis in both arteries a possible cause of primary thrombophilia. -

Hidradenitis Suppurativa (Acne Inversa): Management of a Recalcitrant Disease

STATE-OF-THE-ART REVIEW Editor: Bernard A. Cohen, M.D. Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 24 No. 5 465–473, 2007 Hidradenitis Suppurativa (Acne inversa): Management of a Recalcitrant Disease Joseph Lam, M.D.,* Andrew C. Krakowski, M.D.,* and Sheila F. Friedlander, M.D. *Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine (Dermatology), San Diego School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, California Abstract: Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic relapsing disorder of follicular occlusion that is often recalcitrant to therapy. Topical and systemic antibiotics, hormonal therapies, oral retinoids, immunosuppressant agents, and surgical treatment are some of the therapeutic alternatives used for this often recalcitrant and frequently troublesome disorder. This article reviews the pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa, an evidence-based analy- sis of standard treatments, and recent advances in the therapy of this disorder. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a disease of the (2,3), with the inflammation of apocrine glands that oc- apocrine gland-bearing areas of the body that commonly curs likely representing a secondary phenomenon affects the intertriginous areas. Although it may initially resulting from follicular plugging (3). It is now believed present in a mild form, recurrent abscesses with the that HS is primarily an inflammatory disorder of the hair development of sinus tracts and scarring generally en- follicle and, therefore, is included in the follicular occlu- sues. Rather than a distinct disease entity, it may repre- sion tetrad along with acne conglobata, dissecting cellu- sent the severe end of a spectrum of disease that includes litis, and pilonidal sinuses (4) (Table 1). -

Review Article

DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2146 REVIEW ARTICLE SKIN MANIFESTATIONS OF GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASES: A REVIEW Manisha Nijhawan1, Puneet Agarwal2, Sandeep Nijhawan3, Prashant4, Abhishek Saini5 HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Manisha Nijhawan, Puneet Agarwal, Sandeep Nijhawan, Prashant, Abhishek Saini. “Skin Manifestations of Gastrointestinal Diseases: A Review”. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2014; Vol. 3, Issue 09, March 3; Page: 2357-2372, DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2146 ABSTRACT: Skin is the largest organ of human body and stands as a guard for our internal organs. It can be regarded as a mirror giving a reflection of metabolic, biochemical and functional status of our internal organs. Dermatologists/Gastroenterologist should be aware of the dermatological manifestations as these change may be the first clue that a patient has underlying gastrointestinal (GI) or liver disease. Recognizing these signs is important in early and appropriate diagnosis. This article reviews the important dermatological manifestation of various GI and liver diseases. KEYWORDS: Skin and GI. Different dermatological manifestation in gastrointestinal diseases can be classified as:- 1) Specific skin manifestations 2) Reactive skin manifestations 3) Skin manifestations secondary to the deficiency of nutrients due to GI disease 4) Skin manifestations secondary to the treatment For clinician skin manifestation can be simply classified as- 1. Dermatological manifestations in benign GI diseases 2. Dermatological manifestations in malignant GI disease J of Evolution of Med and Dent Sci/ eISSN- 2278-4802, pISSN- 2278-4748/ Vol. 3/ Issue 09/ Mar 3, 2014 Page 2357 DOI: 10.14260/jemds/2014/2146 REVIEW ARTICLE A: Skin manifestations in esophageal diseases: Dysphagia: Esophageal webs This is a developmental abnormality with one or more horizontal membrane in upper esophagus.