Immersive Theatre: Engaging the Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

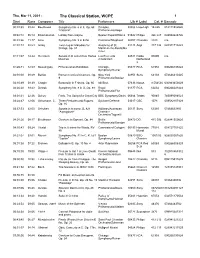

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Mar 11, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 39:42 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Dresden 03086 LaserLight 15 825 018111582520 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Kegel 00:42:1205:14 Khachaturian Lullaby from Gayne Boston Pops/Williams 01542 Philips 426 247 028942624726 00:48:2611:17 Arne Symphony No. 3 in E flat Cantilena/Shepherd 00957 Chandos 8403 n/a 01:01:13 08:54 Grieg Two Elegiac Melodies for Academy of St. 01144 Argo 417 132 028941713223 Strings, Op. 34 Martin-in-the-Fields/Ma rriner 01:11:0714:24 Reincken Sonata in D minor from Hortus Les Eléments 04531 Radio 93009 n/a Musicus Amsterdam Netherland s 01:26:3132:59 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Chicago 05877 RCA 61958 090266195824 Symphony/Reiner 02:01:00 08:49 Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture, Op. New York 02950 Sony 64103 074646410325 9 Philharmonic/Boulez 02:10:4908:39 Chopin Barcarolle in F sharp, Op. 60 Idil Biret 07436 Naxos 8.554536 636943453629 02:20:2839:23 Dvorak Symphony No. 8 in G, Op. 88 Royal 01377 RCA 60234 090266023424 Philharmonic/Flor 03:01:2122:26 Delius Paris, The Song of a Great City BBC Symphony/Davis 06684 Teldec 90845 745099084523 03:24:4712:06 Schumann, C. Three Preludes and Fugues, Sylviane Deferne 03017 CBC 1078 059582107829 Op. 16 03:37:53 22:03 Schubert Sonata in A minor, D. 821 Williams/Australian 05137 Sony 63385 07464633850 "Arpeggione" Chamber Orchestra/Tognetti 04:01:2608:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. -

Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre

Masters i Constructing the Sensorium: Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre A dissertation submitted by Paul Masters in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama Tufts University May 2016 Adviser: Natalya Baldyga Masters ii Abstract: Associated with a broad range of theatrical events and experiences, the term immersive has become synonymous with an experiential, spectacle-laden brand of contemporary theatre. From large-scale productions such as Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More (2008, 2011) to small-scale and customizable experiences (Third Rail Projects, Shunt, and dreamthinkspeak), marketing campaigns and critical reviews cite immersion as both a descriptive and prescriptive term. Examining technologies and conventions drawn from a range of so-called immersive events, this project asks how these productions refract and replicate the technological and ideological constructs of the digital age. Traversing disciplines such as posthumanism, contemporary art, and gaming studies, immersion represents an extension of a cultural landscape obsessed with simulated realities and self-surveillance. As an aesthetic, immersive events rely on sensual experiences, narrative agency, and media installations to convey the presence and atmosphere of otherworldly spaces. By turns haunting, visceral, and seductive spheres of interaction, these theatres also engage in a neoliberal project: one that pretends to greater freedoms than traditional theater while delimiting freedom and concealing the boundaries -

The Tragedy of Macbeth William Shakespeare 1564–1616

3HAKESPEARean DrAMA The TRAGedy of Macbeth Drama by William ShakESPEARE READING 2B COMPARe and CONTRAST the similarities and VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML12-346A DIFFERENCes in classical plaYs with their modern day noVel, plaY, or film versions. 4 EVALUAte how THE STRUCTURe and elements of drAMA -EET the AUTHOR CHANGe in the wORKs of British DRAMAtists across literARy periods. William ShakESPEARe 1564–1616 In 1592—the first time William TOAST of the TOwn In 1594, Shakespeare Shakespeare was recognized as an actor, joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the poet, and playwright—rival dramatist most prestigious theater company in Robert Greene referred to him as an England. A measure of their success was DId You know? “upstart crow.” Greene was probably that the theater company frequently jealous. Audiences had already begun to performed before Queen Elizabeth I and William ShakESPEARe . notice the young Shakespeare’s promise. her court. In 1599, they were also able to • is oFten rEFERRed To as Of course, they couldn’t have foreseen purchase and rebuild a theater across the “the Bard”—an ancienT Celtic term for a poet that in time he would be considered the Thames called the Globe. greatest writer in the English language. who composed songs The company’s domination of the ABOUT heroes. Stage-Struck Shakespeare probably London theater scene continued • INTRODUCed more than arrived in London and began his career after Elizabeth’s Scottish cousin 1,700 new wORds inTo in the late 1580s. He left his wife, Anne James succeeded her in 1603. James the English languagE. Hathaway, and their three children behind became the patron, or chief sponsor, • has had his work in Stratford. -

Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester R M Johnson Phd 2020

Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester R M Johnson PhD 2020 Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester RACHEL MARGARET JOHNSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by Manchester Metropolitan University 2020 Abstract My dissertation demonstrates how a new and distinctive musical culture developed in the industrialising society of early Victorian Manchester. It challenges a number of existing narratives relating to the history of music in nineteenth-century Britain, and has implications for the way we understand the place of music in other industrial societies and cities. The project is located at the nexus between musicology, cultural history and social history, and draws upon ideas current in urban studies, ethnomusicology and anthropology. Contrary to the oft-repeated claim that it was Charles Hallé who ‘brought music to Manchester’ when he arrived in 1848, my archival research reveals a vast quantity and variety of music-making and consumption in Manchester in the 1830s and 1840s. The interconnectedness of the many strands of this musical culture is inescapable, and it results in my adoption of ‘networks’ as an organising principle. Tracing how the networks were formed, developed and intertwined reveals just how embedded music was in the region’s social and civic life. Ultimately, music emerges as an agent of particular power in the negotiation and transformation of the concerns inherent within the new industrial city. The dissertation is structured as a series of interconnected case studies, exploring areas as diverse as the music profession, glee and catch clubs, the Hargreaves Choral Society’s programme notes, Mechanics’ Institutions and the early Victorian public music lecture. -

Program Guide July 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW JULY/EARLY AUGUST 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE JULY/EARLY AUGUST PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete Saturday prime time television schedule begins on page 2. The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 6:30am Arthur 9:00am Curious George 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:30am A Wider World 7:30am Wild Kratts 10:00am This Old House 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:30am Ask This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:00am Curious George 11:30am Ciao Italia 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:00am Sesame Street 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:00pm Sesame Street 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am -

Making Macbeth Funny: a Case for Comedic Adaptation of Shakespeare’S Tragic Play

MAKING MACBETH FUNNY: A CASE FOR COMEDIC ADAPTATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S TRAGIC PLAY A thesis submitted to the faculty of // ^ San Francisco State University ^ r In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Theatre Arts by Emily Ann Stapleton San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Emily Ann Stapleton 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Making Macbeth Funny: A Case For Comedic Adaptation Of Shakespeare’s Tragic Play by Emily Ann Stapleton, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Theatre Arts at San Francisco State University Bruce R. Aveiy, PhD Professor of Theatre Arts Professor of Theatre Arts/Creative Writing MAKING MACBETH FUNNY: A CASE FOR COMEDIC ADAPTATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S TRAGIC PLAY Emily Ann Stapleton San Francisco, California 2018 This thesis both explores and promotes the value in adapting William Shakespeare’s tragic play, Macbeth, into a comedy. The research focuses first on establishing key differences between tragedy and comedy with special attention to the fundamental tragic characteristics of Macbeth in its original form. The study then turns to close examination of three notable comedic adaptations of Macbeth, assessing the adapting playwrights’ specific approaches and techniques as well as the cultural/social commentaries they effectively communicate through their comical conversions. The thesis culminates in an understanding of the immense power in comically retelling tragic stories. i I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this thesis. -

Breaking Down the Fourth Wall with Artaud, Punchdrunk, and the Wooster Group

Belmont University Belmont Digital Repository Belmont Undergraduate Research Symposium (BURS) Special Events 4-11-2019 Breaking Down the Fourth Wall with Artaud, Punchdrunk, and the Wooster Group Megan Huggins Belmont University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.belmont.edu/burs Part of the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Huggins, Megan, "Breaking Down the Fourth Wall with Artaud, Punchdrunk, and the Wooster Group" (2019). Belmont Undergraduate Research Symposium (BURS). 8. https://repository.belmont.edu/burs/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Events at Belmont Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Belmont Undergraduate Research Symposium (BURS) by an authorized administrator of Belmont Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Megan Huggins TDR 3510 Theatre History I Fall 2018 1 Breaking Down the Fourth Wall with Artaud, Punchdrunk, and the Wooster Group Innovations in technology change the way people connect, and storytelling must adapt and evolve to keep up. In theatre, smarter technology creates more intricate designs and improves the use of lights, sound, costumes, and sets to support storytelling in bold ways. With these innovations, welcoming the audience into a story becomes more natural and more personal. These advances blend easily with Antonin Artaud’s vision of a shocking Theatre of Cruelty that connects audiences to the actors and stories in more profound, more emotional ways. Many companies worldwide have grown out of Artaud’s vision of theatre, including the Wooster Group and Punchdrunk. How do these theatre groups use Artaud’s principles to break the fourth wall with their storytelling, and what effect does this have on modern audiences? By incorporating Artaud’s ideas, the Wooster Group’s Hamlet and Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More use technology, design, and audience participation to eliminate the boundaries in theatre and bring classics to the contemporary world. -

Fandom and Punchdrunk's Sleep No More

Fandom and Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More Audience Ethnography of Immersive Dance Julia M. Ritter As I approach the McKittrick Hotel on 27th Street in New York City, the venue for Punch drunk’s immersive Macbethinspired production of Sleep No More, the scene outside resem bles a nightclub queue — people waiting for entry, chatting excitedly. Upon entering, we all go through the same routine: checking coats and bags, and paying for admittance. The ticket is a playing card and each person gets a different suit at random — heart, diamond, spade, club. We are directed to a dimly lit staircase and climb quietly, minds and bodies focused on mounting each step safely. The darkness deepens as we reach the landing and enter a pitchblack corridor Julia M. Ritter is Chair and Artistic Director for the Dance Department at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University. She completed her PhD in Dance at Texas Woman’s University and has received two awards for her research on dance and immersive performance, including the 2016 Cohen Lecture Award from the Selma Jeanne Cohen Fund for International Scholarship on Dance (USA), and the 2014 Prix André G. Bourassa for Creative Research from Le Société Québécoise D’Etudes Théâtrales (Canada). She is the recipient of three Fulbright awards for her choreographic projects in Europe. [email protected] TDR: The Drama Review 61:4 (T236) Winter 2017. ©2017 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 59 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00692 by guest on 02 October 2021 that twists and turns sharply; the portentous soundscape is foreboding. -

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in the New Production Premiere

Educator’s Guide Photo: Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Željko Lucˇi´c and Maria Guleghina as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in the new production premiere. Macbeth January 12, 2008 THE WORK Macbeth: MACBETH Composed by Giuseppe Verdi A Play and an Opera Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave Verdi's Macbeth whips Shakespeare's tale of power, corruption, and Andrea Maffei and devilry into an emotional whirlwind. Macbeth's goriness Based on the play by William Shakespeare alone might assure its appeal to adolescents. The plot thickens with intrigue, not to mention the fascinating interplay between First performed 1847 in Florence, Italy; premiere of revised version 1865, Paris, the title character and his diabolical wife. France. The Metropolitan Opera production brings these themes to life. In Adrian Noble’s conception, Macbeth takes place in a world of literal darkness. Here light is as likely the bringer of terror as of salvation. Players emerge from perpetual night in THE MET PRODUCTION costumes evoking contemporary urban warfare, supported by James Levine, Conductor mobs, claques, and revolutionary throngs. Adrian Noble, Production Whether or not your students are familiar with Shakespeare’s play, Verdi’s Macbeth offers riches of its own—in music, in the Starring: Maria Guleghina (Lady Macbeth) arcs of relationships, and in themes. This guide offers a variety of experiences designed to enrich viewing of the Met’s Live in Lado Ataneli (Macbeth) HD transmission of Macbeth—to generate anticipation, heighten John Relyea (Banquo) enjoyment, and promote understanding for audience members Dimitri Pittas (Macduff) young and old. 2 Macbeth: An Intimate THE GUIDE INCLUDES FOUR TYPES OF ACTIVITIES Look at Lust and Justice • Two full-length activities, designed to support your ongoing curriculum. -

Punchdrunk Audience Development: What We Can Learn from Their Processes

PUNCHDRUNK: A CASE STUDY Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Master of Science in Arts Administration Drexel University By Laura M. Keegan, B.F.A. * * * * * Drexel University 2013 Approved by Dr. Jean Brody, D.F.A Advisor Graduate Program in Arts Administration Copyright by Laura M Keegan 2013 ABSTRACT This case study investigates the growth and development of Punchdrunk, a United Kingdom (U.K.) based Theater Company. Punchdrunk‟s dedication to its aesthetic and brand, combined with dual leadership, creative marketing and inventive partnerships have positioned the organization to reach large audiences and remain nimble in an unstable sector. This paper finds that this organization has risen to the challenge of maintaining artistic integrity and remaining sustainable, challenges which are faced by all nonprofit arts organizations. The combination of traditional funding mechanisms, alternative revenues, creative partnerships and corporate sponsorship enable Punchdrunk to continue to pursue their ambitious mission: to transform the passive consumption of the arts into life changing experiences for everyone. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to Punchdrunk‟s leadership, cast and volunteers. Executive Director, Colin Marsh was very kind to offer access to the U.S. premiere of Sleep No More in Boston, Massachusetts. In late February 2010, the organization also welcomed participation in their New York production both as a volunteer and as an audience member. In addition, I would like to personally thank the Arts Administration team at Drexel University, my friends and family and especially, my partner, Jeremy Burrell for his assistance proofreading and editing. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................