Punchdrunk Audience Development: What We Can Learn from Their Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

Macbeth for Kids Study Guide

Sacramento Theatre Company Study Guide The Macbeth For Kids From the book by Lois Burdett and Christine Coburn Based on William Shakespeare's Macbeth Study Guide Materials Compiled by Anna Miles 1 Sacramento Theatre Company Mission Statement The Sacramento Theatre Company (STC) strives to be the leader in integrating professional theatre with theatre arts education. STC produces engaging professional theatre, provides exceptional theatre training, and uses theatre as a tool for educational engagement. Our History The theatre was originally formed as the Sacramento Civic Repertory Theatre in 1942, an ad hoc troupe formed to entertain locally-stationed troops during World War II. On October 18, 1949, the Sacramento Civic Repertory Theatre acquired a space of its own with the opening of the Eaglet Theatre, named in honor of the Eagle, a Gold Rush-era theatre built largely of canvas that had stood on the city’s riverfront in the 1850s. The Eaglet Theatre eventually became the Main Stage of the not-for-profit Sacramento Theatre Company, which evolved from a community theatre to professional theatre company in the 1980s. Now producing shows in three performance spaces, it is the oldest theatre company in Sacramento. After five decades of use, the Main Stage was renovated as part of the H Street Theatre Complex Project. Features now include an expanded and modernized lobby and a Cabaret Stage for special performances. The facility also added expanded dressing rooms, laundry capabilities, and other equipment allowing the transformation of these performance spaces, used nine months of the year by STC, into backstage and administration places for three months each summer to be used by California Musical Theatre for Music Circus. -

Furious: Myth, Gender, and the Origins of Lady Macbeth

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Furious: Myth, Gender, and the Origins of Lady Macbeth Emma King The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3431 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FURIOUS: MYTH, GENDER, AND THE ORIGINS OF LADY MACBETH by EMMA KING A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 ii © 2019 EMMA KING All Rights Reserved iii Furious: Myth, Gender, and the Origins of Lady Macbeth by Emma King This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Tanya Pollard Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Furious: Myth, Gender, and the Origins of Lady Macbeth by Emma King This thesis attempts to understand the fabulously complex and poisonously unsettling Lady Macbeth as a product of classical reception and intertextuality in early modern England. Whence comes her “undaunted mettle” (1.7.73)? Why is she, like the regicide she helps commit, such a “bloody piece of work” (2.3.108)? How does her ability to be “bloody, bold, and resolute” (4.1.81), as Macbeth is commanded to be, reflect canonical literary ideas, early modern or otherwise, regarding women, gender, and violence? Approaching texts in the literary canon as the result of transformation and reception, this research analyzes the ways in which Lady Macbeth’s gender, motivations, and words can be understood as inherently intertextual. -

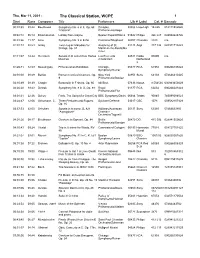

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Mar 11, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 39:42 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Dresden 03086 LaserLight 15 825 018111582520 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Kegel 00:42:1205:14 Khachaturian Lullaby from Gayne Boston Pops/Williams 01542 Philips 426 247 028942624726 00:48:2611:17 Arne Symphony No. 3 in E flat Cantilena/Shepherd 00957 Chandos 8403 n/a 01:01:13 08:54 Grieg Two Elegiac Melodies for Academy of St. 01144 Argo 417 132 028941713223 Strings, Op. 34 Martin-in-the-Fields/Ma rriner 01:11:0714:24 Reincken Sonata in D minor from Hortus Les Eléments 04531 Radio 93009 n/a Musicus Amsterdam Netherland s 01:26:3132:59 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Chicago 05877 RCA 61958 090266195824 Symphony/Reiner 02:01:00 08:49 Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture, Op. New York 02950 Sony 64103 074646410325 9 Philharmonic/Boulez 02:10:4908:39 Chopin Barcarolle in F sharp, Op. 60 Idil Biret 07436 Naxos 8.554536 636943453629 02:20:2839:23 Dvorak Symphony No. 8 in G, Op. 88 Royal 01377 RCA 60234 090266023424 Philharmonic/Flor 03:01:2122:26 Delius Paris, The Song of a Great City BBC Symphony/Davis 06684 Teldec 90845 745099084523 03:24:4712:06 Schumann, C. Three Preludes and Fugues, Sylviane Deferne 03017 CBC 1078 059582107829 Op. 16 03:37:53 22:03 Schubert Sonata in A minor, D. 821 Williams/Australian 05137 Sony 63385 07464633850 "Arpeggione" Chamber Orchestra/Tognetti 04:01:2608:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. -

Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre

Masters i Constructing the Sensorium: Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre A dissertation submitted by Paul Masters in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama Tufts University May 2016 Adviser: Natalya Baldyga Masters ii Abstract: Associated with a broad range of theatrical events and experiences, the term immersive has become synonymous with an experiential, spectacle-laden brand of contemporary theatre. From large-scale productions such as Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More (2008, 2011) to small-scale and customizable experiences (Third Rail Projects, Shunt, and dreamthinkspeak), marketing campaigns and critical reviews cite immersion as both a descriptive and prescriptive term. Examining technologies and conventions drawn from a range of so-called immersive events, this project asks how these productions refract and replicate the technological and ideological constructs of the digital age. Traversing disciplines such as posthumanism, contemporary art, and gaming studies, immersion represents an extension of a cultural landscape obsessed with simulated realities and self-surveillance. As an aesthetic, immersive events rely on sensual experiences, narrative agency, and media installations to convey the presence and atmosphere of otherworldly spaces. By turns haunting, visceral, and seductive spheres of interaction, these theatres also engage in a neoliberal project: one that pretends to greater freedoms than traditional theater while delimiting freedom and concealing the boundaries -

The Historical Context of Macbeth

The Historical Context of Macbeth EXPLORING Shakespeare, 2003 Shakespeare wrote Macbeth sometime between 1605 and 1606, shortly after the ascension of King James of Scotland to the English throne. The new monarch brought Scotland—previously known to the English only as a mysterious, conquered neighbor—into the public limelight. The period of James' reign was further marked by political and religious conflict, much of which focused the kingdom's attention on the danger of regicide. Events in History at the Time of the Play Sources Following the process used in the creation of many of his plays, Shakespeare drew the plot for Macbeth from historical sources—particularly Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1577), the authoritative historical text of the period. Although Holinshed contains the story of Macbeth and Duncan, Shakespeare did not rely on this only; rather, he combined different stories and different versions of the same story to create his drama. The Chronicles include an account of King Malcolm II (reigned 1005-34), whose throne passed first to Duncan I (reigned 1034-40) and then to Macbeth (reigned 1040-57), both of whom were his grandsons. For his portrayal of the murder through which Macbeth took Duncan's throne, Shakespeare mined another vein of the Chronicles—King Duff's death at the hands of one of his retainers, Donwald. In combining the two events, Shakespeare crafted a specific tone for the tale of regicide. When King Malcolm II of Scotland died in 1034, his last command was that the throne should pass to his oldest grandson, Duncan. -

The Tragedy of Macbeth William Shakespeare 1564–1616

3HAKESPEARean DrAMA The TRAGedy of Macbeth Drama by William ShakESPEARE READING 2B COMPARe and CONTRAST the similarities and VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML12-346A DIFFERENCes in classical plaYs with their modern day noVel, plaY, or film versions. 4 EVALUAte how THE STRUCTURe and elements of drAMA -EET the AUTHOR CHANGe in the wORKs of British DRAMAtists across literARy periods. William ShakESPEARe 1564–1616 In 1592—the first time William TOAST of the TOwn In 1594, Shakespeare Shakespeare was recognized as an actor, joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the poet, and playwright—rival dramatist most prestigious theater company in Robert Greene referred to him as an England. A measure of their success was DId You know? “upstart crow.” Greene was probably that the theater company frequently jealous. Audiences had already begun to performed before Queen Elizabeth I and William ShakESPEARe . notice the young Shakespeare’s promise. her court. In 1599, they were also able to • is oFten rEFERRed To as Of course, they couldn’t have foreseen purchase and rebuild a theater across the “the Bard”—an ancienT Celtic term for a poet that in time he would be considered the Thames called the Globe. greatest writer in the English language. who composed songs The company’s domination of the ABOUT heroes. Stage-Struck Shakespeare probably London theater scene continued • INTRODUCed more than arrived in London and began his career after Elizabeth’s Scottish cousin 1,700 new wORds inTo in the late 1580s. He left his wife, Anne James succeeded her in 1603. James the English languagE. Hathaway, and their three children behind became the patron, or chief sponsor, • has had his work in Stratford. -

Roman Polanski's MACBETH

20 Riddling Whiteness, Riddling Certainty: Roman Polanski’s M ACBETH Francesca Royster Against Reading as White in Shakespeare Studies In her poem “Passing” from her book The Land of Look Behind, Michelle Cliff writes: Isolate yourself. If they find out about you it’s all over. Forget about your great-grandfather with the darkest skin—until you’re back “home” where they joke about how he climbed a coconut tree when he was eighty. Go to college. Go to England to study. Learn about the Italian Renaissance and forget that they kept slaves. Ignore the tears of the Indians. Black Americans don’t under- stand us either. We are—after all—British. If anyone asks you, talk about sugar plantations and the Maroons—not the landscape of downtown Kingston or the children at the roadside. Be selective. Cultivate normalcy. Stress sameness. Blend in. For God’s sake don’t pile difference upon difference. It’s not safe. (Cliff 23) Though I am not a black Jamaican, Cliff’s is the position that I know intimately, the “Black-Eyed Squint,” to borrow Ghanaian writer Ama Ata Aidoo’s subtitle from her book, Our Sister KillJoy. Perhaps this is why I have been particularly interested in images of whiteness gone wrong, not-quite whiteness, moments where we see the gaps in a unified sense of white iden- tity, from Titus Andronicus to Antony and Cleopatra. My view of Shakespearean studies has always been from the outside of whiteness and Britishness, through a gaze that has become (for the necessity of my health) oppositional. -

Renaissance and Reformation, 1998

Intertextual Madness in HILAIRE Hamlet: The Ghost's KALLENDORF Fragmented Performativity Summary: This essay establishes King James I's Daemonologie and Regi- nald Scot's Discouerie of Witchcraft as intertexts for Hamlet. It demonstrates how the diabolical linguistic register borrowed from these intertexts both heightens the verisimilitude ofHamlet 's madness and expands the performative potential of the Ghost. Performativity has often been discussed as a theme for this play, but usually only in relation to Hamlet himself This essay avoids the reductionism of the "Ghost critics" and extends the performativity theme to the Ghost as well by offering him a diabolical mask to try on in addition to his many others, Performativity is "a specular technique that breaks up the action into acting-out, rehearsals and try-outs for a dramatic action that endlessly threatens (or promises) to revert to its theatrical origins, to collapse into theatricality."^ In a play such as Hamlet, where performativity is arguably one of the primary themes of the work, there are dramatic resources and resonances which would not be possible without the intertextual use of a diabolical linguistic register. The madness in Hamlet becomes more verisim- ilar because it is associated intertextually with demonic possession, and the Ghost appears more frightening because one of his intertextual masks is devilish. The purpose of this essay will be to demonstrate the intertextual use of the demonic register in the play and to explore the theme of per- formativity as one of its ramifications. Let us pause for a moment at the outset to reflect on the nature of intertextuality and how it can illuminate our understanding of a play involved Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, XXII, 4 (1998) /69 70 / Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme in this process. -

Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester R M Johnson Phd 2020

Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester R M Johnson PhD 2020 Musical Networks in Early Victorian Manchester RACHEL MARGARET JOHNSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by Manchester Metropolitan University 2020 Abstract My dissertation demonstrates how a new and distinctive musical culture developed in the industrialising society of early Victorian Manchester. It challenges a number of existing narratives relating to the history of music in nineteenth-century Britain, and has implications for the way we understand the place of music in other industrial societies and cities. The project is located at the nexus between musicology, cultural history and social history, and draws upon ideas current in urban studies, ethnomusicology and anthropology. Contrary to the oft-repeated claim that it was Charles Hallé who ‘brought music to Manchester’ when he arrived in 1848, my archival research reveals a vast quantity and variety of music-making and consumption in Manchester in the 1830s and 1840s. The interconnectedness of the many strands of this musical culture is inescapable, and it results in my adoption of ‘networks’ as an organising principle. Tracing how the networks were formed, developed and intertwined reveals just how embedded music was in the region’s social and civic life. Ultimately, music emerges as an agent of particular power in the negotiation and transformation of the concerns inherent within the new industrial city. The dissertation is structured as a series of interconnected case studies, exploring areas as diverse as the music profession, glee and catch clubs, the Hargreaves Choral Society’s programme notes, Mechanics’ Institutions and the early Victorian public music lecture.