Breaking Down the Fourth Wall with Artaud, Punchdrunk, and the Wooster Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A TASTE of SHAKESPEARE: MACBETH a 52 Minute Video Available for Purchase Or Rental from Bullfrog Films

A TASTE OF SHAKESPEARE MACBETH Produced by Eugenia Educational Foundation Teacher’s Guide The video with Teacher’s Guide A TASTE OF SHAKESPEARE: MACBETH a 52 minute video available for purchase or rental from Bullfrog Films Produced in Association with BRAVO! Canada: a division of CHUM Limited Produced with the Participation of the Canadian Independent Film & Video Fund; with the Assistance of The Department of Canadian Heritage Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the support of The Ontario Trillium Foundation: an agency of the Ministry of Culture The Catherine & Maxwell Meighen Foundation The Norman & Margaret Jewison Foundation George Lunan Foundation J.P. Bickell Foundation Sir Joseph Flavelle Foundation ©2003 Eugenia Educational Foundation A Taste of Shakespeare: Macbeth Program Description A Taste of Shakespeare is a series of thought-provoking videotapes of Shakespeare plays, in which actors play the great scenes in the language of 16th and 17th century England, but comment on the action in the English of today. Each video is under an hour in length and is designed to introduce the play to students in high school and college. The teacher’s guide that comes with each video gives – among other things – a brief analysis of the play, topics for discussion or essays, and a short list of recom- mended reading. Production Notes At the beginning and end of this blood- soaked tragic play Macbeth fights bravely: loyal to his King and true to himself. (It takes nothing away from his valour that in the final battle King and self are one.) But in between the first battle and the last Macbeth betrays and destroys King, country, and whatever is good in his own nature. -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

From 'Scottish' Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of Blood

arts Article From ‘Scottish’ Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood Dolores P. Martinez Emeritus Reader, SOAS, University of London, London WC1H 0XG, UK; [email protected] Received: 16 May 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 10 September 2018 Abstract: Shakespeare’s plays have become the subject of filmic remakes, as well as the source for others’ plot lines. This transfer of Shakespeare’s plays to film presents a challenge to filmmakers’ auterial ingenuity: Is a film director more challenged when producing a Shakespearean play than the stage director? Does having auterial ingenuity imply that the film-maker is somehow freer than the director of a play to change a Shakespearean text? Does this allow for the language of the plays to be changed—not just translated from English to Japanese, for example, but to be updated, edited, abridged, ignored for a large part? For some scholars, this last is more expropriation than pure Shakespeare on screen and under this category we might find Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo¯ 1957), the subject of this essay. Here, I explore how this difficult tale was translated into a Japanese context, a society mistakenly assumed to be free of Christian notions of guilt, through the transcultural move of referring to Noh theatre, aligning the story with these Buddhist morality plays. In this manner Kurosawa found a point of commonality between Japan and the West when it came to stories of violence, guilt, and the problem of redemption. Keywords: Shakespeare; Kurosawa; Macbeth; films; translation; transcultural; Noh; tragedy; fate; guilt 1. -

Theatre I Moderator: Jaclynn Jutting, M.F.A

2019 Belmont University Research Symposium Theatre I Moderator: Jaclynn Jutting, M.F.A. April 11, 2019 3:30 PM-5:00 PM Johnson Center 324 3:30 p.m. - 3:45 p.m. Accidentally Pioneering a Movement: How the Pioneer Players Sparked Political Reform Sami Hansen Faculty Advisor: James Al-Shamma, Ph.D. Theatre in the twenty-first century has been largely based on political and social reform, mirroring such movements as Black Lives Matter and Me Too. New topics and ideas are brought to life on various stages across the globe, as many artists challenge cultural and constitutional structures in their society. But how did protest theatre get started? As relates specifically to the feminist movement, political theatre on the topic of women’s rights can be traced back to an acting society called the Pioneer Players, which was made up of British men and women suffragettes in the early twentieth century. The passion and drive of its members contributed to its success: over the course of a decade, patrons and actors worked together to expose a rapidly changing society to a variety of genres and new ideas. In this presentation, I hope to prove that, in challenging traditional theatre, the Pioneer Players helped to pave the way for the avant garde, spur political reform, and promote uncensored theatre in Great Britain. Their efforts facilitated a transformation of the stage that established conditions under which political theatre could, and did, flourish. 3:45 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. Philip Glass: A Never-Ending Circular Staircase Joshua Kiev Faculty Advisor: James Al-Shamma, Ph.D. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES on Particular Attention to the Dialogue Between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth: It Will Provide MACBETH Valuable Clues

ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES ON particular attention to the dialogue between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth: it will provide MACBETH valuable clues. Devise a legend and make sure all plans are clear. Students share their work with the other groups. MACBETH DILEMMAS Preparing to stage a play involves asking CONVERSATIONS FOR TWO questions and pursuing solutions to problems and difficulties. The questions our directors, This improvisational activity will help students designers and actors asked themselves about think about the themes of the story. With a Macbeth were similar to those that follow. Have partner, students brainstorm different scenarios your class try to find their own answers. to fit the following situations. They then carry out a conversation. If comfortable, they can share 1. Text their conversations with the rest of the class. Make a list of the characters in Macbeth who Discuss the different choices made by pairs tell the truth when they talk to other working with the same scenario. characters, and another list of those who lie. What do these two lists tell you about the 1. Two friends discuss their visit to a fortune atmosphere of the play? About its characters? teller at the local fair and discover that they About how these characters could be acted? have both been told they will get a date with the same boy or girl. 2. Costumes 2. A man discusses with his wife how he will What should King Duncan look like? How old have to betray a co-worker to get a desired is he? How vigorous? What should he wear? promotion. -

Lady Macbeth, the Ill-Fated Queen

LADY MACBETH, THE ILL-FATED QUEEN: EXPLORING SHAKESPEAREAN THEMES OF AMBITION, SEXUALITY, WITCHCRAFT, PATRILINEAGE, AND MATRICIDE IN VOCAL SETTINGS OF VERDI, SHOSTAKOVICH, AND PASATIERI BY 2015 Andrea Lynn Garritano ANDREA LYNN GARRITANO Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of The University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz ________________________________ Prof. Joyce Castle ________________________________ Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Kip Haaheim ________________________________ Dr. Martin Bergee Date Defended: December 19, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for ANDREA LYNN GARRITANO Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: LADY MACBETH, THE ILL-FATED QUEEN: EXPLORING SHAKESPEAREAN THEMES OF AMBITION, SEXUALITY, WITCHCRAFT, PATRILINEAGE, AND MATRICIDE IN VOCAL SETTINGS OF VERDI, SHOSTAKOVICH, AND PASATIERI ______________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz Date approved: January 31, 2015 iii Abstract This exploration of three vocal portrayals of Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth investigates the transference of themes associated with the character is intended as a study guide for the singer preparing these roles. The earliest version of the character occurs in the setting of Verdi’s Macbeth, the second is the archetypical setting of Lady Macbeth found in the character Katerina Ismailova from -

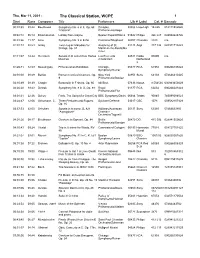

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Mar 11, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 39:42 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 Dresden 03086 LaserLight 15 825 018111582520 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Kegel 00:42:1205:14 Khachaturian Lullaby from Gayne Boston Pops/Williams 01542 Philips 426 247 028942624726 00:48:2611:17 Arne Symphony No. 3 in E flat Cantilena/Shepherd 00957 Chandos 8403 n/a 01:01:13 08:54 Grieg Two Elegiac Melodies for Academy of St. 01144 Argo 417 132 028941713223 Strings, Op. 34 Martin-in-the-Fields/Ma rriner 01:11:0714:24 Reincken Sonata in D minor from Hortus Les Eléments 04531 Radio 93009 n/a Musicus Amsterdam Netherland s 01:26:3132:59 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Chicago 05877 RCA 61958 090266195824 Symphony/Reiner 02:01:00 08:49 Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture, Op. New York 02950 Sony 64103 074646410325 9 Philharmonic/Boulez 02:10:4908:39 Chopin Barcarolle in F sharp, Op. 60 Idil Biret 07436 Naxos 8.554536 636943453629 02:20:2839:23 Dvorak Symphony No. 8 in G, Op. 88 Royal 01377 RCA 60234 090266023424 Philharmonic/Flor 03:01:2122:26 Delius Paris, The Song of a Great City BBC Symphony/Davis 06684 Teldec 90845 745099084523 03:24:4712:06 Schumann, C. Three Preludes and Fugues, Sylviane Deferne 03017 CBC 1078 059582107829 Op. 16 03:37:53 22:03 Schubert Sonata in A minor, D. 821 Williams/Australian 05137 Sony 63385 07464633850 "Arpeggione" Chamber Orchestra/Tognetti 04:01:2608:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. -

Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre

Masters i Constructing the Sensorium: Neoliberalism and Aesthetic Practice in Immersive Theatre A dissertation submitted by Paul Masters in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama Tufts University May 2016 Adviser: Natalya Baldyga Masters ii Abstract: Associated with a broad range of theatrical events and experiences, the term immersive has become synonymous with an experiential, spectacle-laden brand of contemporary theatre. From large-scale productions such as Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More (2008, 2011) to small-scale and customizable experiences (Third Rail Projects, Shunt, and dreamthinkspeak), marketing campaigns and critical reviews cite immersion as both a descriptive and prescriptive term. Examining technologies and conventions drawn from a range of so-called immersive events, this project asks how these productions refract and replicate the technological and ideological constructs of the digital age. Traversing disciplines such as posthumanism, contemporary art, and gaming studies, immersion represents an extension of a cultural landscape obsessed with simulated realities and self-surveillance. As an aesthetic, immersive events rely on sensual experiences, narrative agency, and media installations to convey the presence and atmosphere of otherworldly spaces. By turns haunting, visceral, and seductive spheres of interaction, these theatres also engage in a neoliberal project: one that pretends to greater freedoms than traditional theater while delimiting freedom and concealing the boundaries -

'House of Cards' Arrives As a Netflix Series

‘House of Cards’ Arrives as a Netflix Series - NYTimes.com http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/20/arts/television/house-of-cards... January 18, 2013 By BRIAN STELTER EARLY in the new Netflix series “House of Cards” the narrator and card player Representative Francis Underwood, played by Kevin Spacey, looks straight into the camera and tells viewers: “Power is a lot like real estate. It’s all about location, location, location. The closer you are to the source, the higher your property value.” Underwood is speaking at a presidential inauguration, just outside the Capitol in Washington. As viewers observe the swearing-in he asks in a delicious Southern drawl, “Centuries from now, when people watch this footage, who will they see smiling just at the edge of the frame?” Then Underwood comes into frame again. He’s just a few rows away from the president. He gives the camera a casual wave. Underwood, having been spurned in his bid to become secretary of state, is on a quest for power that’s just as suspenseful as anything on television. But his story will unspool not on TV but on Netflix, the streaming video service that is investing hundreds of millions of dollars in original programming. Its plan for showing “House of Cards,” an adaptation of a 1990 BBC mini-series set in Parliament, will itself be a departure from the usual broadcast approach. On Feb. 1 all 13 episodes will be available at once, an acknowledgment that many of its subscribers like to watch shows in marathon sessions. Another 13 episodes are already in production. -

The Tragedy of Macbeth William Shakespeare 1564–1616

3HAKESPEARean DrAMA The TRAGedy of Macbeth Drama by William ShakESPEARE READING 2B COMPARe and CONTRAST the similarities and VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML12-346A DIFFERENCes in classical plaYs with their modern day noVel, plaY, or film versions. 4 EVALUAte how THE STRUCTURe and elements of drAMA -EET the AUTHOR CHANGe in the wORKs of British DRAMAtists across literARy periods. William ShakESPEARe 1564–1616 In 1592—the first time William TOAST of the TOwn In 1594, Shakespeare Shakespeare was recognized as an actor, joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the poet, and playwright—rival dramatist most prestigious theater company in Robert Greene referred to him as an England. A measure of their success was DId You know? “upstart crow.” Greene was probably that the theater company frequently jealous. Audiences had already begun to performed before Queen Elizabeth I and William ShakESPEARe . notice the young Shakespeare’s promise. her court. In 1599, they were also able to • is oFten rEFERRed To as Of course, they couldn’t have foreseen purchase and rebuild a theater across the “the Bard”—an ancienT Celtic term for a poet that in time he would be considered the Thames called the Globe. greatest writer in the English language. who composed songs The company’s domination of the ABOUT heroes. Stage-Struck Shakespeare probably London theater scene continued • INTRODUCed more than arrived in London and began his career after Elizabeth’s Scottish cousin 1,700 new wORds inTo in the late 1580s. He left his wife, Anne James succeeded her in 1603. James the English languagE. Hathaway, and their three children behind became the patron, or chief sponsor, • has had his work in Stratford.