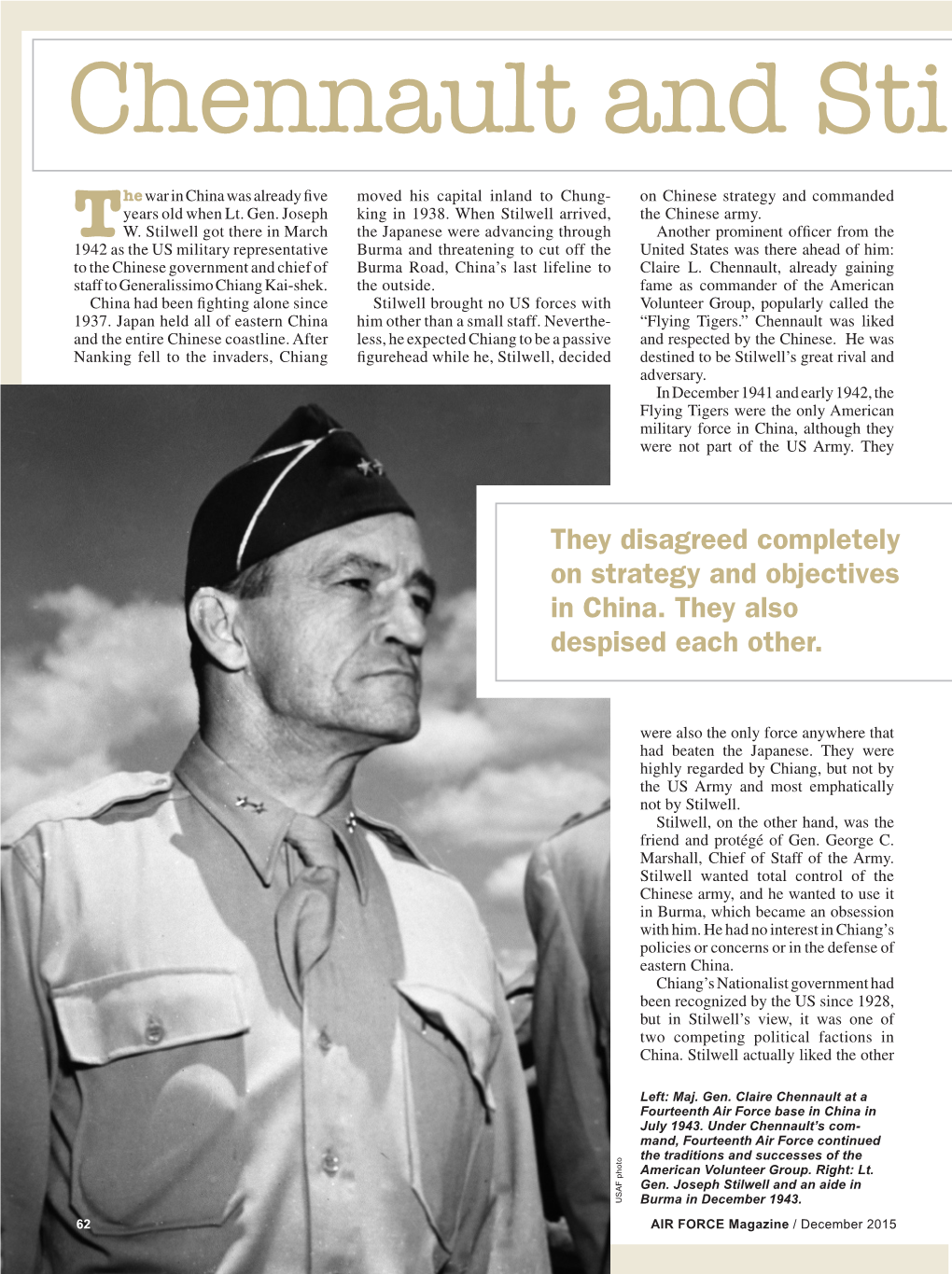

Chennault and Sti Lwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

ALBERTA SECURITIES COMMISSION DECISION Citation

ALBERTA SECURITIES COMMISSION DECISION Citation: Re Global 8 Environmental Technologies, Inc., 2015 ABASC 734 Date: 20150605 Global 8 Environmental Technologies, Inc., Halo Property Services Inc., Canadian Alternative Resources Inc., Milverton Capital Corporation, Rene Joseph Branconnier and Chad Delbert Burback Panel: Kenneth Potter, QC Fred Snell, FCA Appearing: Robert Stack, Liam Oddie and Heather Currie for Commission Staff H. Roderick Anderson for René Joseph Branconnier Patricia Taylor for Chad Delbert Burback Daniel Wolf for Global 8 Environmental Technologies, Inc. Submissions Completed: 26 November 2014 Decision: 5 June 2015 5176439.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................... 1 A. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1. G8 .................................................................................................................1 2. Halo and CAR ..............................................................................................2 B. History of the Proceedings ...................................................................................... 2 C. Certain Prior Orders ................................................................................................ 3 D. Summary of Conclusion ......................................................................................... 3 II. PROCEDURAL AND EVIDENTIARY MATTERS -

Joseph Warren Stilwell Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf958006qb Online items available Register of the Joseph Warren Stilwell papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee, revised by Lyalya Kharitonova Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003, 2014, 2015, 2017 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Joseph Warren 51001 1 Stilwell papers Title: Joseph Warren Stilwell papers Date (inclusive): 1889-2010 Collection Number: 51001 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 93 manuscript boxes, 16 oversize boxes, 1 cubic foot box, 4 album boxes, 4 boxes of slides, 7 envelopes, 1 oversize folder, 3 sound cassettes, sound discs, maps and charts, memorabilia(57.4 Linear Feet) Abstract: Diaries, correspondence, radiograms, memoranda, reports, military orders, writings, annotated maps, clippings, printed matter, sound recordings, and photographs relating to the political development of China, the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945, and the China-Burma-India Theater during World War II. Includes some subsequent Stilwell family papers. World War II diaries also available on microfilm (3 reels). Transcribed copies of the diaries are available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org Creator: Stilwell, Joseph Warren, 1883-1946 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 36-38 and 40 may only be used one folder at a time. Box 39 closed; microfilm use copy available. Boxes 67, 72-73, 113, and 117 restricted; use copies available in Box 116. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. -

Instruction 10-1204 1 June 2006

BY ORDER OF THE COMMANDER AIR FORCE SPACE COMMAND AIR FORCE SPACE COMMAND INSTRUCTION 10-1204 1 JUNE 2006 Operations SATELLITE OPERATIONS COMPLIANCE WITH THIS PUBLICATION IS MANDATORY NOTICE: This publication is available digitally on the AFDPO WWW site at: http://www.e-publishing.af.mil. OPR: A3FS (Lt Col Kirk Jester) Certified by: A3F (Col David Jones) Pages: 22 Distribution: F This instruction implements Air Force Policy Directive (AFPD) 10-12, Space, Air Force Instruction (AFI) 10-1201, Space Operations and United States Space Command Policy Directive (UPD) 10-39, Sat- ellite Disposal Procedures (UPD 10-39 is being updated to a Strategic Command Directive (SD)), by establishing guidance and procedures for satellite operations and disposal. It applies to Headquarters Air Force Space Command (HQ AFSPC) and all subordinate units utilizing dedicated satellite control assets or common use and/or unique resources of the Air Force Satellite Control Network (AFSCN), except for Royal Air Force (RAF) Telemetry and Command Squadron (TCS), Oakhanger. This instruction applies to Air National Guard (ANG) and Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) units with satellite control respon- sibilities. Submit changes to HQ AFSPC/A3F, Global Space Operations Division, 150 Vandenberg St., Ste 1105, Peterson AFB CO 80914-4250. If there is a conflict between this instruction and unit, contractor or other major command publications, this instruction applies. Maintain and dispose of records created as a result of prescribed processes in accordance with Air Force Records Disposition Schedule (RDS) which may be found on-line at https://afrims.amc.af.mil. The previous Air Force Space Command Instruction (AFSPCI) 10-1204, dated 1 September 1998, was rescinded in 2001. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

![The American Legion [Volume 135, No. 3 (September 1993)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8754/the-american-legion-volume-135-no-3-september-1993-278754.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 135, No. 3 (September 1993)]

I THE AMERICAN \ %%>^^ Legiom^ FOR GOD AND COUNTRY September 1993 Two Dollars HOME SCHflOUHB, Going To School By Staying Home It's Warm, it's Hefty, it's Handsome and it's 100% Acrylic Easy Care! Grey Use this coupon and grab yourself a couple today! Cardigan Sweater Q5 2 for 49.50 3 for 74.00 HAB 24 4 for 98.50 lOOFainiew HABAND COMPANY Prospect Park 100 Fairview Ave., Prospect Park, N J 07530 Send 07530 I Regular Sizes: S(34-36) M{38-40) L(42-44) XL(46-4£ sweaters, *Big Men Sizes: Add $4 each for cable knit I Handsome have enclosed 2XL(50-52) 3XL(54-56) 4XL(58-60) both front and back WHAT HOW is an expensive fealLir purchase price plus $3.50 7A7-72C SIZE? MANY? an amazing low pi le Burgundy postage and handling. A ECRU Check Enclosed B GREY D BURGUNDY 1 CARD # Name . Mail Addr ;ss ' Apt. # City 1 State Zip The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. 135, No. 3 ARTICLES September 1993 RETiraNG GRADUALLY By Gordon Williams 18 VA RESEARCH: WE ALL SeiEHT AWxnt^ VA research has improvedAmericans' health, budget cuts now threaten thisprogram. By Ken Schamberg 22 TO SCHOOL BY STAYING AT I More and more parents believe they can succeed at home where schools havefailed. By Deidre Sullivan 25 To dramatize the dangers, activists have been playingfast and loose with the numbers. By Steve Salerno 28 THE GHOST PLANE FROM MINDANAO You may have the information to help solve this WWII mystery. FAMILY TIES: LONGER UVES Centenarians reveal the secret oftheir long and healthy lives. -

1 Skydance Media and Alibaba Pictures Join Forces To

SKYDANCE MEDIA AND ALIBABA PICTURES JOIN FORCES TO FINANCE AND PRODUCE FLYING TIGERS FEATURE FILM Oscar-Nominated Writer Randall Wallace to Script _____________________________________________________________________________ Santa Monica, CA and Beijing, China – April 6, 2016 – Skydance, a diversified media company that creates elevated, event-level entertainment for global audiences, and Alibaba Pictures, Alibaba Group’s entertainment affiliate, today announced that they will join forces to finance and produce a Flying Tigers feature film for global release. It has been designated by Skydance Media and Alibaba Pictures as a high-priority development project. The screenplay will be written by Oscar-nominated writer Randall Wallace (Braveheart) and the film will be produced by David Ellison and Dana Goldberg of Skydance together with a team from Alibaba Pictures. The Flying Tigers – formally known as the 1st American Volunteer Group of the Chinese Air Force – was a group of volunteer pilots from the U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps. Led by Captain Claire Lee Chennault, the group fought alongside the Chinese during World War II. The Flying Tigers project will tell the story of the unique brotherhood formed by these intrepid soldiers. “This production partnership with Alibaba Pictures on Flying Tigers marks an important next step in our strategy to expand the reach of the Skydance brand on a global basis,” said David Ellison, Chief Executive Officer of Skydance Media. “We could not be more excited to work with the incomparable Randall Wallace to bring to life the extraordinary, untold story of the great commitment and sacrifices made by this courageous group of pilots.” “Flying Tigers carries with it a rich legacy and a movie about this subject matter has been highly anticipated for a very long time,” added Zhang Wei, President of Alibaba Pictures. -

Military-Industrial Complex: Eisenhower's Unsolved Problem

MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX: EISENHOWER'S UNSOLVED PROBLEM by )/lrS THOMAS JENKINS BADGER Bo A., George Washington University., 1949 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted fn pa 1 ful 111b nt of the .'_-. -.- ... — -\-C MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1965 Approved by: ~ Major Professor XOOl 1105 6<3 ACKHQWLEOGEMENT TO: Dr. Louis Douglas for suggesting the subject, offering continuous encouragement and valuable advice, and insisting upon a measure of scholar- ship. Or. Robin Higham for reading the manuscript, professional advice and suggestions. Dr. Joseph Hajda, who as the Major Professor, was responsible for the thesis and who tirelessly read and reread drafts, and who patiently pointed out weaknesses needing amplification, correction, or deletion. It Is not Intended to Indicate that these gentlemen concur with the entire thesis. They don't. The errors and misconceptions In the thesis are mine as well as the conclusions but without their assistance the thesis would be unacceptable as a scholarly work. If I could have followed their advice more Intelligently the thesis would be considerably Improved, but whatever merit this work may have the credit belongs to them. CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION of the United One hundred and sixty-eight years ago, the first President had served so States presented his farewell address to the country which he from a divided well and which he, as much as any other person, had changed Washington's group of self-oriented states Into a cohesive nation. George permanent alliances principal advice to this young nation was to stay clear of west to settle} with foreign nations. -

Australia's Political System

Australia’s Political System Australia's Political System Australia's system of government is based on the liberal democratic tradition, which includes religious tolerance and freedom of speech and association. It's institutions and practices reflect British and North American models but are uniquely Australian. The Commonwealth of Australia was created on January 1, 1901 - Federation Day - when six former British colonies - now the six States of Australia - agreed to form a union. The Australian Constitution, which took effect on January 1, 1901, lays down the framework for the Australian system of government. The Constitution The Australian Constitution sets out the rules and responsibilities of government and outlines the powers of its three branches - legislative, executive and judicial. The legislative branch of government contains the parliament - the body with the legislative power to make laws. The executive branch of government administers the laws made by the legislative branch, and the judicial branch of government allows for the establishment of the country's courts of law and the appointment and removal of it judges. The purpose of the courts is to interpret all laws, including the Constitution, making the rule of law supreme. The Constitution can only be changed by referendum. Australia's Constitutional Monarchy Australia is known as a constitutional monarchy. This means it is a country that has a queen or king as its head of state whose powers are limited by a Constitution. Australia's head of state is Queen Elizabeth II. Although she is also Queen of the United Kingdom, the two positions now are quite separate, both in law and constitutional practice. -

Flynn,John T.- While You Slept (PDF)

While You Slept Other Books by John T. Flynn THE ROOSEVELT MYTH THE ROAD AHEAD: AMERICA'S CREEPING REVOLUTION While You Slept OUR TRAGEDY IN ASIA AND WHO MADE IT by JOHN T. FLYNN THE DEVIN-ADAIR COMPANY New York · 1951 Copyright 1951 by John T. Flynn. All rights reserved. Permission to reprint material from this book must be obtained in writing from the publisher. For information write: The Devin-Adair Company, 23 East 26th St., New York 10, N. Y. First Printing, November 1951 Second Printing, November 1951 Third Printing, December 1951 Fourth Printing, January 1952 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents I While You Slept 9 II The Red Deluge 13 III China's Two Wars 14 IV Two Great Designs 25 V Architects of Disaster 30 VI The Road to Korea Opens 44 VII The Great Whitewash 54 VIII The Pool of Poison 59 IX The Hatchet Men 71 X Left Thunder on the Right 82 XI The Press and Pink Propaganda 88 XII Red Propaganda in the Movies 98 XIII Poison in the Air 108 XIV The Institute of Pacific Relations 116 XV The Amerasîa Case 134 XVI The Great Swap 145 XVII The China War 151 XVIII The Blunders That Lost a Continent 157 XIX America s Two Wars 178 References 187 While You Slept I While You Slept As June 1950 drew near, America was giving little attention to a place called Korea. Secretary General Trygve Lie of the United Nations was urging that Chiang Kai-shek's govern- ment be expelled from the United Nations to make room for the Chinese Communist government of Mao Tse-tung. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/02/2021 09:03:16PM Via Free Access Andrew Higson

1 5 From political power to the power of the image: contemporary ‘British’ cinema and the nation’s monarchs Andrew Higson INTRODUCTION: THE HERITAGE OF MONARCHY AND THE ROYALS ON FILM From Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V Shakespeare adaptation in 1989 to the story of the fi nal years of the former Princess of Wales, inDiana in 2013, at least twenty-six English-language feature fi lms dealt in some way with the British monarchy. 1 All of these fi lms (the dates and directors of which will be indi- cated below) retell more or less familiar stories about past and present kings and queens, princes and princesses. This is just one indication that the institution of monarchy remains one of the most enduring aspects of the British national heritage: these stories and characters, their iconic settings and their splendid mise-en-scène still play a vital role in the historical and contemporary experience and projection of British national identity and ideas of nationhood. These stories and characters are also of course endlessly recycled in the pre- sent period in other media as well as through the heritage industry. The mon- archy, its history and its present manifestation, is clearly highly marketable, whether in terms of tourism, the trade in royal memorabilia or artefacts, or images of the monarchy – in paintings, prints, fi lms, books, magazines, televi- sion programmes, on the Internet and so on. The public image of the monarchy is not consistent across the period being explored here, however, and it is worth noting that there was a waning of support for the contemporary royal family in the 1990s, not least because of how it was perceived to have treated Diana. -

Vol 9 Issue 3 Hof.Indd

Air Commando JOURNAL Publisher Air Commando Norm Brozenick / [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Association Paul Harmon / [email protected] Managing Editor Air Commando Association Board of Directors Richard Newton Chairman of the Board : Maj Gen Norm Brozenick, USAF (Ret) Senior Editor Scott McIntosh / [email protected] President: Col Dennis Barnett, USAF (Ret) Contributing Editor Vice President: Ron Dains CMSgt Bill Turner, USAF (Ret) Treasurer: Contributing Editor Col David Mobley, USAF (Ret) Joel Higley Public Affairs/Marketing Director Executive Director: Maj Gen Rich Comer, USAF (Ret) Melissa Gross / [email protected] Directors: Graphic Designer CMSgt Tom Baker, USAF (Ret) Jeanette Elliott / [email protected] CMSgt Heather Bueter, USAF (Ret) Col Steve Connelly, USAF (Ret) Lt Col Max Friedauer, USAF (Ret) “The Air Commando Journal... Lt Col Chris Foltz, USAF (Ret) SMSgt Hollis Tompkins, USAF (Ret) Massively Successful! I save all mine.” Additional Positions & Advisors: Lt Gen Marshall “Brad” Webb SES Bill Rone, (Ret) Executive Financial Advisor Former AFSOC Commander Col Jerry Houge, USAF (Ret) Chaplain (Used with permission by Lt Gen Webb) CMSgt Mike Gilbert, USAF (Ret) Attorney Sherri Hayes, GS-15, (Ret) Civilian Advisor Mike Moore, Financial Development Advisor ADVERTISERS IN THIS ISSUE Air Commando Association ......................................................... 52 The Air Commando Journal publication is free to all current members of the Air Commando Association. Anytime Flight Members ............................................................