Wuthering Heights 1,364

Total Page:16

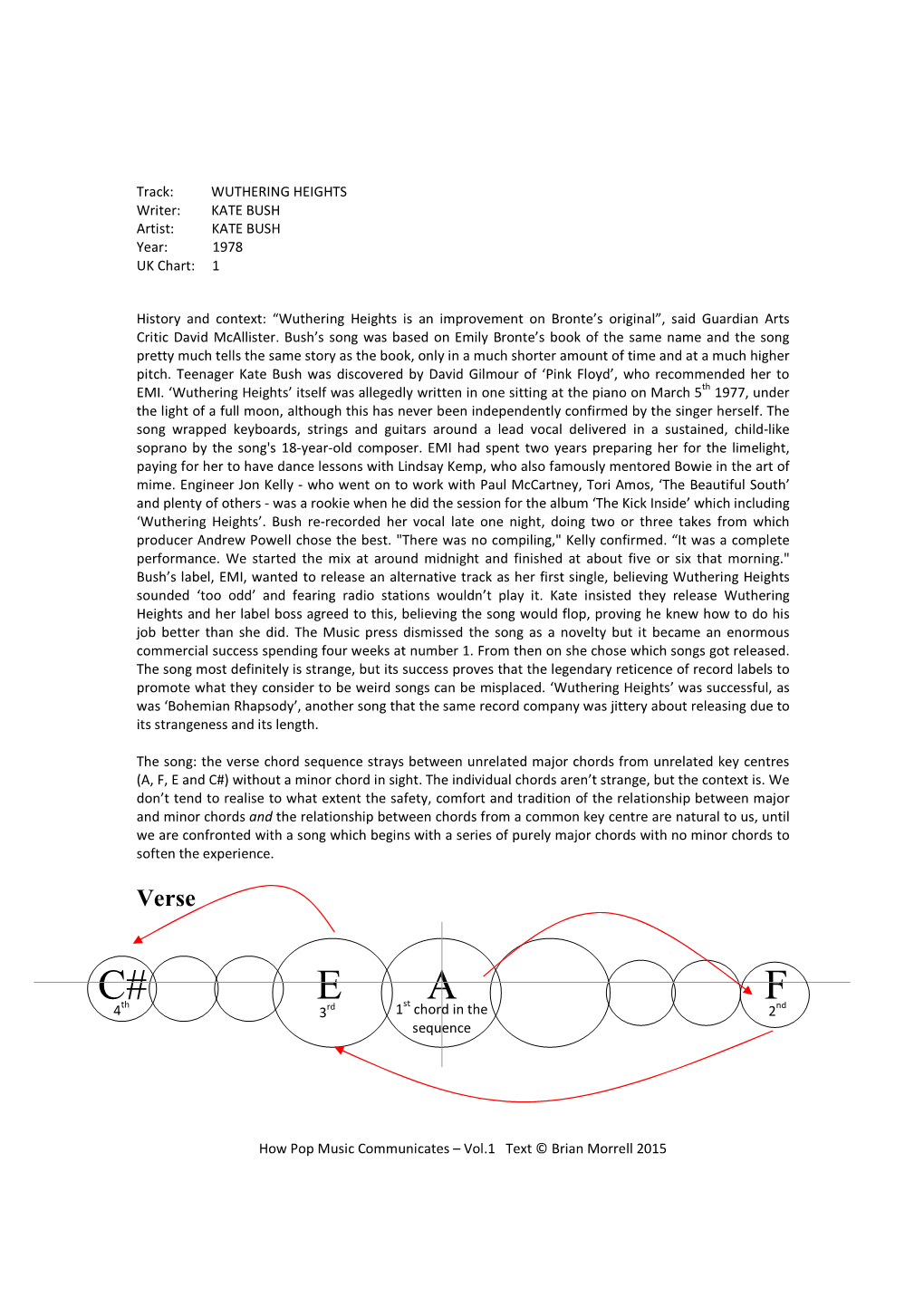

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre: Deadly Versus Healing Fantasy in the Lives and Works of the Brontes

The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research Volume 1 Article 7 1997 Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre: Deadly Versus Healing Fantasy in the Lives and Works of the Brontes Jeanne Moose St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Moose, Jeanne. "Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre: Deadly Versus Healing Fantasy in the Lives and Works of the Brontes." The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research 1 (1997): 49-66. Web. [date of access]. <https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol1/iss1/7>. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol1/iss1/7 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre: Deadly Versus Healing Fantasy in the Lives and Works of the Brontes Abstract In lieu of an abstract, below is the article's first paragraph. Dreams and fantasies provide humans with a means of escape from everyday reality. According to Sigmund Freud, dreams carry one "off into another world" (Strachey, 1900, 7). Their aim is to free us from our everyday life (Burdach, 1838, 499) and to provide us with the opportunity to fantasize about how we would like our lives to be or to imagine our lives as worse than they are so that we can cope with our current situation. -

New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 080, No 150, 7/14/1977." 80, 150 (1977)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1977 The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 7-14-1977 New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 080, No 150, 7/ 14/1977 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1977 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 080, No 150, 7/14/1977." 80, 150 (1977). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1977/77 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1977 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ..... - ..• - ... -' -·· '")".~ ~ {; fl ,.;v'l (\ ..... _.--~. ..A -. '• I ~~~ ·' f ¢'1~·. '181. : i I lAN'"'OG.\ ...V l ..... ·E·-~. .-·m~·! .l ~, ..-.~ ~~~~~ :, -- - !,'1 e-g··e· ncy '4.' •, # .. i '<;" • t ... -:·:: ., ., i ' ' .. - ,.. ..)_: '' .. '\ ··~· ~ .'{' ' ·~ ' ., ..., · ·Rldu•d·L· ~lleib«r .". , ·? '~;;a~a<lemic.cQmmunity,'' · ·· · · hospital has had s()me horrendous ,. • ·Four ._.emergency ·-medicih!=.cl9c;;.¢ ·. Th.~. ~llief complaint voiced.by ·financial·problemsin thelast-_ye$1. ,-, ..,, ~ · tors from the emer~en~ roor.rr at !:th~;· phy~icians was· the -~~~k ()f Nobody l,la$ bousht anything· new .t.•"'"" 7 ~; · · BCMC .. have ' submitted their'· eguipment and support from tbe .the the last year, incl\lding the •fl resignations effective July J. T.heir .. ho,Spital. · Marburs said that the · emers~O,fY; r~om.'' . Napolitano_ .is . <•)) · ·res•snatioQs leav~- · only· .. on" . ideal . emergency room situation the. dean··.· p( · the: ·UNM · Medical ','1 ,,' '. emersency m-edicine specialists ·at · · would· igclude· seven. or ,eislii ~hoot . -

1 Wuthering Heights (William Wyler, 1939; Robert Fuest, 1970; Jacques

1 Wuthering Heights (William Wyler, 1939; Robert Fuest, 1970; Jacques Rivette, 1985; Peter Kosminsky, 1992) Wyler’s ghastly sentimental version concedes nothing to the proletariat: with the exception of Leo G. Carroll, who discards his usual patrician demeanour and sports a convincing Yorkshire accent as Joseph, all the characters are as bourgeois as Sam Goldwyn could have wished. Not even Flora Robson as Ellen Dean – she should have known better – has the nerve to go vocally downmarket. Heathcliff may come from the streets of Liverpool, and may have been brought up in the dales, but Olivier’s moon-eyed Romeo-alternative version of him (now and again he looks slightly dishevelled, and slightly malicious) comes from RADA and nowhere else. Any thought that Heathcliff is diabolical, or that either he or Catherine come from a different dimension altogether was, it’s clear, too much for Hollywood to think about. Couple all this with Merle Oberon’s flat face, white makeup, too-straight nose and curtailed hairstyles, and you have a recipe for disaster. We’re alerted to something being wrong when, on the titles, the umlaut in Emily’s surname becomes an acute accent. Oberon announces that she “ is Heathcliff!” in some alarm, as if being Heathcliff is the last thing she’d want to be. When Heathcliff comes back, he can of course speak as high and mightily as one could wish – and does: and the returned Olivier has that puzzled way of looking straight through a person as if they weren’t there which was one of his trademarks (see left): for a moment the drama looks as if it might ratchet up a notch or two. -

THE SABETHA Local Officials Confirm Sabetha Mumps Case

THE SABETHA SINCE 1876 WEEKLY RECIPE VIC’S GUN SHOP Vic Halls has passion for WEDNESDAY Chicken & Ramen Salad shooting that spans 40 years. MAR FUN&GAMES 8B SPORTS&RECREATION 1B 15 2017 ILLNESS Local officials confirm Sabetha mumps case HERALD REPORT Fifty-six cases of the contagious disease - mumps - have been re- ported by the Kansas Depart- ment of Health and Environment (KDHE). A letter was sent home with Sabetha students on Wednes- day, March 8, acknowledging a possible case of mumps among its students at Sabetha High School. The Kansas USA Wrestling community also issued a press re- lease on Thursday, March 9, con- firming that mumps transmission had been documented at several wrestling tournaments in Kansas. One case has been confirmed - in Sabetha, said Jane Sunderland, Nemaha County Community Health Services administrator. Other Kansas counties affect- - to questions and help out whenever possible. How ed by mumps include Atchison, ever, you have to be aware if you ask six beekeepers Barton, Crawford, Douglas, Ellis, one questions, you will likely receive 13 different Finney, Franklin, Johnson, Mar- answers or solutions to your problem. Beekeeping- shall, Riley, Rooks and Thomas. is a hobby that I am convinced will always be a KDHE has not identified all of including the previous White House Administra learning process.” the sources of these mumps in- Tedmans embarktion on expediting ‘T-House the EPA [Environmental Honey’ Protection beekeepingAfter learning the basics ofproject beekeeping, Matt fections, which means “yet to be Agency] to approve new chemical treatments for a and Michelle installed their first hives just out identified kids or adults may still HEATHER STEWART mite that was devastating the beekeeping/pollination side of Sabetha city limits with packaged bees spread the disease at other wres- industry,” Matt said. -

Harmoniske Særegenheter I Alternativ Pop

Harmoniske særegenheter i alternativ pop Miriam Ekvik Masteroppgave Institutt for musikkvitenskap Universitetet i Oslo Våren 2011 II Forord Jeg vil først rette en stor takk til min hovedveileder Anne Danielsen for konstruktiv kritikk, nyttige råd og meget god oppfølging. En stor takk rettes også til min biveileder Asbjørn Ø. Eriksen for detaljerte tilbakemeldinger og ”aha”-opplevelser. Tusen takk til Catherine Kontz i French for Cartridge og til Stephan Sieben og Putte Johander i Sekten for uvurderlige svar på e-post. Tusen takk til Sofia Rentzhog for hjelp til notering av teksten på ‟Himlen slukar träden‟. Tusen takk til Tor Sivert Gunnes som spiller fiolin på ‟Left behind‟. Takk til min søster Linda Ekvik for gjennomlesninger og gode tips. Takk til familien min for støtte og forståelse gjennom hele prosessen. Til sist tusen takk til min samboer Ingvild for oppmuntring, inspirerende samtaler og for tålmodighet med en nevrotisk student. Oslo, april 2011 M.E. III IV Innhold Kapittel 1 – Innledning ............................................................................................................... 1 Problemstilling ....................................................................................................................... 2 Metoder og teori ..................................................................................................................... 3 Harmonisk analyse i populærmusikk i forhold til harmonisk analyse i kunstmusikk ....... 8 Bakgrunn for valg av musikk .............................................................................................. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

The Affect on Plot and Character in the Brontë Sisters' Novels

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2014 Motherless Women Writers: The Affect on Plot and Character in the Brontë Sisters’ Novels Laci J. Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Laci J., "Motherless Women Writers: The Affect on Plot and Character in the Brontë Sisters’ Novels" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 187. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/187 This Honors Thesis - Withheld is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Motherless Women Writers: The Affect on Plot and Character in the Brontë Sisters’ Novels Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors By Laci Baker The Honors College Midway Honors Program East Tennessee State University April 11, 2014 Laci Baker, Author Dr. Judith B. Slagle, Faculty Mentor Dr. Michael Briggs, Faculty Reader Dr. Phyllis Thompson, Faculty Reader 2 Introduction to Thesis: The idea that an author’s heritage and environment can be reflected in the plotline of his/her narratives and in the development of each character is thought-provoking; while it is true that an author’s voice may not be the same as the narrator’s voice, the work is still influenced by the author and his/her perception of the characters, their world, and their journey. -

250 Evacuados Por Un Error En Las Catas Para Las Obras Del Metro

250 evacuados por un error en las catas para El primer diario que no se vende las obras del Metro Viernes 8 ABRIL DE 2005. AÑO VI. NÚMERO 1229 La sombra del Carmel cae sobre Granada. La constructora provoca un escape de gas barrio del Camino de Ronda. 3.600 plazas de guardería para el curso al perforar la tubería que suministra al Todos que viene, 400 más que este año los comercios cercanos y tres bloques de pisos tuvieron que ser desalojados. 2 El plazo de solicitud se acaba el 6 de mayo. 3 El traslado del ferial a la Vega esconde fines especulativos, según los vecinos Anuncian movilizaciones si el Ayuntamiento per- siste en su propuesta de realizar el cambio. 3 El Papa se planteó dimitir hace cinco años por el párkinson Lo revela el propio Juan Pablo II en su testa- mento, conocido íntegramente ayer. 8 Gastamos 108 euros al mes en comida Crece el consumo de aceite, vino de marca, platos preparados y derivados de la leche. 10 Desarticulado el ‘complejo Donosti’ de ETA tras otras tres detenciones En lo que va de año ya van 50 detenidos por su re- lación con la banda terrorista. 10 Ola de frío primaveral desde hoy Los termómetros bajarán entre dos y ocho grados y no se recuperarán hasta el domingo. 12 Un tatarabuelo de 7 millones de años Es la calavera del Chad y saca un millón de años a los restos encontrados en Kenia, hasta ahora los tutiplán más antiguos, y algo más a los de Etiopía. -

Popular Music 27:02 Reviews

University of Huddersfield Repository Colton, Lisa Kate Bush and Hounds of Love. By Ron Moy. Ashgate, 2007. 148 pp. ISBN 978-0-7546-5798-9 (pb) Original Citation Colton, Lisa (2008) Kate Bush and Hounds of Love. By Ron Moy. Ashgate, 2007. 148 pp. ISBN 978-0-7546-5798-9 (pb). Popular Music, 27 (2). pp. 329-331. ISSN 0261-1430 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/2875/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Reviews 329 the functions and (social) interactions of the body as a defined biological system and ultimate representation of the self can be said to form the core of the argument. The peculiar discourse that arises from this kind of emphasis leads to a mesmerising and occasionally amusing line of progression endowing the book with a highly ramified structure, almost in itself an example of a maximalist procedure. -

Silsbee 1 Wuthering Heights : a Tale of Romantic Horror The

Silsbee 1 Wuthering Heights: A Tale of Romantic Horror The Romantic literary tradition has long been difficult to pin down and describe accurately. Arthur Lovejoy noted the variety and conflict of opinion amusingly in his 1923 address to an annual meeting of the Modern Language Association of America. He listed experts who attributed the rise of Romanticism variously to Rousseau, Kant, Plato, and the Serpent in the Garden of Eden, and noted “that many of these originators of Romanticism...figure on other lists as initiators or representatives of tendencies of precisely the contrary sort” (230). Movements in th the middle of the 20 century—most notably led by René Wellek—tried to create a homogenized sense of European Romanticism, but more recent efforts have once again fractured that paradigm (McGann). Wuthering Heights is, however, generally described as a Romantic work, often in the colloquial as well as literary sense, and Heathcliff is often considered the epitome of a Byronic hero. In spite of the prevalence of these labels, Emily Brontë's treatment of Heathcliff, Catherine and the relationship between them seems more like a critique of both traditions than an endorsement or glorification of either. The suggestion of Heathcliff as a Byronic hero is introduced before the reader has a chance to really understand who he is. Lockwood's description of him upon their first meeting is our first glimpse: He is a dark-skinned gypsy in aspect, in dress and manners a gentleman...rather slovenly, perhaps, yet not looking amiss with his negligence, because he has an erect and handsome figure—and rather morose—possibly some people might suspect him of a degree of under-bred pride...I know, by instinct, his reserve springs from an Silsbee 2 aversion to showy displays of feeling...He'll love and hate, equally under cover.. -

What Questions Should Historians Be Asking About UK Popular Music in the 1970S? John Mullen

What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s? John Mullen To cite this version: John Mullen. What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s?. Bernard Cros; Cornelius Crowley; Thierry Labica. Community in the UK 1970-79, Presses universi- taires de Paris Nanterre, 2017, 978-2-84016-287-2. hal-01817312 HAL Id: hal-01817312 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01817312 Submitted on 17 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s? John Mullen, Université de Rouen Normandie, Equipe ERIAC One of the most important jobs of the historian is to find useful and interesting questions about the past, and the debate about the 1970s has partly been a question of deciding which questions are important. The questions, of course, are not neutral, which is why those numerous commentators for whom the key question is “Did the British people become ungovernable in the 1970s?” might do well to balance this interrogation with other equally non-neutral questions, such as, perhaps, “Did the British elites become unbearable in the 1970s?” My reflection shows, it is true, a preoccupation with “history from below”, but this is the approach most suited to the study of popular music history. -

The Alan Parsons Project Pyramid Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Alan Parsons Project Pyramid mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pyramid Country: Benelux Released: 1979 Style: Art Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1713 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1359 mb WMA version RAR size: 1382 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 187 Other Formats: ADX MP1 MP3 APE AIFF AU RA Tracklist A1 Voyager 2:24 A2 What Goes Up... 3:31 A3 The Eagle Will Rise Again 4:20 A4 One More River 4:15 A5 Can't Take It With You 5:06 B1 In The Lap Of Gods 5:27 B2 Pyramania 2:45 B3 Hyper-Gamma-Spaces 4:19 B4 Shadow Of A Lonely Man 5:34 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Arista Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Arista Records, Inc. Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Mixed At – Abbey Road Studios Published By – Woolfsongs Ltd. Published By – Careers Music, Inc. Published By – Irving Music, Inc. Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Santa Maria Credits Acoustic Guitar [Acoustic Guitars] – Alan Parsons, David Paton, Ian Bairnson Arranged By [Orchestra And Choir], Conductor [Orchestra And Choir Conducted By] – Andrew Powell Bass – David Paton Chorus Master [Choirmaster] – Bob Howes* Composed By [All Songs] – Alan Parsons, Eric Woolfson Cover, Design – Hipgnosis Drums, Percussion – Stuart Elliot* Electric Guitar [Electric Guitars] – Ian Bairnson Engineer [Assistant Engineers] – Chris Blair, Pat Stapley Engineer [Engineered By] – Alan Parsons Executive-Producer – Eric Woolfson Keyboards – Duncan Mackay, Eric Woolfson Mastered By [Mastering By] – Chris Blair Photography By [Photos] – Hipgnosis , Brimson* Producer [Produced By] – Alan Parsons Vocals – Colin Blunstone, David Paton, Dean Ford, Jack Harris, John Miles, Lenny Zakatek Written-By [All Tracks] – Alan Parsons, Eric Woolfson Notes 12" X 24" insert contains lyrics, credits, and artwork with a poster on the reverse side of the full cover artwork Light blue inner sleeve with no printing.