Principles of Herbal Pharmacology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Options for the Mitigation of Direct Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Livestock: a Review

Animal (2013), 7:s2, pp 220–234 & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2013 animal doi:10.1017/S1751731113000876 Technical options for the mitigation of direct methane and nitrous oxide emissions from livestock: a review - P. J. Gerber1 , A. N. Hristov2, B. Henderson1, H. Makkar1,J.Oh2, C. Lee2, R. Meinen2, F. Montes3,T.Ott2, J. Firkins4, A. Rotz5, C. Dell5, A. T. Adesogan6,W.Z.Yang7, J. M. Tricarico8, E. Kebreab9, G. Waghorn10, J. Dijkstra11 and S. Oosting11 1Agriculture and Consumer protection Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Vialle delle terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy; 2Department of Animal Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA; 3Plant Science Department, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA; 4Department of Animal Sciences, The Ohio State University, Columbus OH 43210, USA; 5Department of Animal Sciences, USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Pasture Systems and Watershed Management Research Unit, University Park, PA 16802, USA; 6University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32608, USA; 7Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge AB, Canada T1J 4B1; 8Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy, Rosemont, IL 60018, USA; 9Department of Animal Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; 10DairyNZ, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand; 11Department of Animal Sciences, Wageningen University, 6700 AH Wageningen, The Netherlands (Received 28 February 2013; Accepted 15 April 2013) Although livestock production accounts for a sizeable share of global greenhouse gas emissions, numerous technical options have been identified to mitigate these emissions. In this review, a subset of these options, which have proven to be effective, are discussed. -

Suspect and Target Screening of Natural Toxins in the Ter River Catchment Area in NE Spain and Prioritisation by Their Toxicity

toxins Article Suspect and Target Screening of Natural Toxins in the Ter River Catchment Area in NE Spain and Prioritisation by Their Toxicity Massimo Picardo 1 , Oscar Núñez 2,3 and Marinella Farré 1,* 1 Department of Environmental Chemistry, IDAEA-CSIC, 08034 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Chemistry, University of Barcelona, 08034 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 3 Serra Húnter Professor, Generalitat de Catalunya, 08034 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 October 2020; Accepted: 26 November 2020; Published: 28 November 2020 Abstract: This study presents the application of a suspect screening approach to screen a wide range of natural toxins, including mycotoxins, bacterial toxins, and plant toxins, in surface waters. The method is based on a generic solid-phase extraction procedure, using three sorbent phases in two cartridges that are connected in series, hence covering a wide range of polarities, followed by liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry. The acquisition was performed in the full-scan and data-dependent modes while working under positive and negative ionisation conditions. This method was applied in order to assess the natural toxins in the Ter River water reservoirs, which are used to produce drinking water for Barcelona city (Spain). The study was carried out during a period of seven months, covering the expected prior, during, and post-peak blooming periods of the natural toxins. Fifty-three (53) compounds were tentatively identified, and nine of these were confirmed and quantified. Phytotoxins were identified as the most frequent group of natural toxins in the water, particularly the alkaloids group. -

Excluded Drug List

Excluded Drug List The following drugs are excluded from coverage as they are not approved by the FDA ACTIVE-PREP KIT I (FLURBIPROFEN-CYCLOBENZAPRINE CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT II (KETOPROFEN-BACLOFEN-GABAPENTIN CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT III (KETOPROFEN-LIDOCAINE-GABAPENTIN CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT IV (TRAMADOL-GABAPENTIN-MENTHOL-CAMPHOR CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT V (ITRACONAZOLE-PHENYTOIN SODIUM CREAM CMPD KIT) ADAZIN CREAM (BENZO-CAPSAICIN-LIDO-METHYL SALICYLATE CRE) AFLEXERYL-LC PAD (LIDOCAINE-MENTHOL PATCH) AFLEXERYL-MC PAD (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL TOPICAL PATCH) AIF #2 DRUG PREPERATION KIT (FLURBIPROFEN-GABAPENT-CYCLOBEN-LIDO-DEXAMETH CREAM COMPOUND KIT) AGONEAZE (LIDOCAINE-PRILOCAINE KIT) ALCORTIN A (IODOQUINOL-HYDROCORTISONE-ALOE POLYSACCHARIDE GEL) ALEGENIX MIS (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL DISK) ALIVIO PAD (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL PATCH) ALODOX CONVENIENCE KIT (DOXYCYCLINE HYCLATE TAB 20 MG W/ EYELID CLEANSERS KIT) ANACAINE OINT (BENZOCAINE OINT) ANODYNZ MIS (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL DISK) APPFORMIN/D (METFORMIN & DIETARY MANAGEMENT CAP PACK) AQUORAL (ARTIFICIAL SALIVA - AERO SOLN) ATENDIA PAD (LIDOCAINE-MENTHOL PATCH) ATOPICLAIR CRE (DERMATOLOGICAL PRODUCTS MISC – CREAM) Page 1 of 9 Updated JANUARY 2017 Excluded Drug List AURSTAT GEL/CRE (DERMATOLOGICAL PRODUCTS MISC) AVALIN-RX PAD (LIDOCAINE-MENTHOL PATCH) AVENOVA SPRAY (EYELID CLEANSER-LIQUID) BENSAL HP (SALICYLIC ACID & BENZOIC ACID OINT) CAMPHOMEX SPRAY (CAMPHOR-HISTAMINE-MENTHOL LIQD SPRAY) CAPSIDERM PAD (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL -

Forensic Features of a Fatal Datura Poisoning Case During a Robbery

Forensic Science International 261 (2016) e17–e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forensic Science International jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/forsciint Case report Forensic features of a fatal Datura poisoning case during a robbery a, a a a a,b E. Le Garff *, Y. Delannoy , V. Mesli , V. He´douin , G. Tournel a Univ Lille, CHU Lille, UTML (EA7367), Service de Me´decine Le´gale, F-59000 Lille, France b Univ Lille, CHU Lille, Laboratoire de Toxicologie, F-59000 Lille, France A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Datura poisonings have been previously described but remain rare in forensic practice. Here, we present Received 2 October 2015 a homicide case involving Datura poisoning, which occurred during a robbery. Toxicological results Received in revised form 28 January 2016 were obtained by second autopsy performed after one previous autopsy and full body embalmment. A Accepted 13 February 2016 35-year-old man presented with severe stomach and digestive pain, became unconscious and ultimately Available online 23 February 2016 died during a trip in Asia. A first autopsy conducted in Asia revealed no trauma, intoxication or pathology. The corpse was embalmed with methanol/formalin. A second autopsy was performed in France, and Keywords: toxicology samples were collected. Scopolamine, atropine, and hyoscyamine were found in the vitreous Forensic humor, in addition to methanol. Police investigators questioned the local travel guide, who admitted to Intoxication Datura having added Datura to a drink to stun and rob his victim. The victim’s death was attributed to disordered Homicide heart rhythm due to severe anticholinergic syndrome following fatal Datura intoxication. -

Understanding and Managing the Transition Using Essential Oils Vs

MENOPAUSE: UNDERSTANDING AND MANAGING THE TRANSITION USING ESSENTIAL OILS VS. TRADITIONAL ALLOPATHIC MEDICINE by Melissa A. Clanton A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Diploma of Aromatherapy 401 Australasian College of Health Sciences Instructors: Dorene Petersen, Erica Petersen, E. Joy Bowles, Marcangelo Puccio, Janet Bennion, Judika Illes, and Julie Gatti TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures............................................................................ iv Acknowledgments........................................................................................ v Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 – Female Reproduction 1a – The Female Reproductive System............................................. 4 1b - The Female Hormones.............................................................. 9 1c – The Menstrual Cycle and Pregnancy....................................... 12 Chapter 2 – Physiology of Menopause 2a – What is Menopause? .............................................................. 16 2b - Physiological Changes of Menopause ..................................... 20 2c – Symptoms of Menopause ....................................................... 23 Chapter 3 – Allopathic Approaches To Menopausal Symptoms 3a –Diagnosis and Common Medical Treatments........................... 27 3b – Side Effects and Risks of Hormone Replacement Therapy ...... 32 3c – Retail Cost of Common Hormone Replacement -

Central Valley Toxicology Drug List

Chloroform ~F~ Lithium ~A~ Chlorpheniramine Loratadine Famotidine Acebutolol Chlorpromazine Lorazepam Fenoprofen Acetaminophen Cimetidine Loxapine Fentanyl Acetone Citalopram LSD (Lysergide) Fexofenadine 6-mono- Clomipramine acetylmorphine Flecainide ~M~ Clonazepam a-Hydroxyalprazolam Fluconazole Maprotiline Clonidine a-Hydroxytriazolam Flunitrazepam MDA Clorazepate Albuterol Fluoxetine MDMA Clozapine Alprazolam Fluphenazine Medazepam Cocaethylene Amantadine Flurazepam Meperidine Cocaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Fluvoxamine Mephobarbital Codeine Amiodarone Fosinopril Meprobamate Conine Amitriptyline Furosemide Mesoridazine Cotinine Amlodipine Methadone Cyanide ~G~ Amobarbital Methanol Cyclobenzaprine Gabapentin Amoxapine d-Methamphetamine Cyclosporine GHB d-Amphetamine l-Methamphetamine Glutethamide l-Amphetamine ~D~ Methapyrilene Guaifenesin Aprobarbital Demoxepam Methaqualone Atenolol Desalkylfurazepam ~H~ Methocarbamol Atropine Desipramine Halazepam Methylphenidate ~B~ Desmethyldoxepin Haloperidol Methyprylon Dextromethoraphan Heroin Metoclopramide Baclofen Diazepam Hexobarbital Metoprolol Barbital Digoxin Hydrocodone Mexiletine Benzoylecgonine Dihydrocodein Hydromorphone Midazolam Benzphetamine Dihydrokevain Hydroxychloroquine Mirtazapine Benztropine Diltiazem Hydroxyzine Morphine (Total/Free) Brodificoum Dimenhydrinate Bromazepam ~N~ Diphenhydramine ~I~ Bupivacaine Nafcillin Disopyramide Ibuprofen Buprenorphine Naloxone Doxapram Imipramine Bupropion Naltrexone Doxazosin Indomethacin Buspirone NAPA Doxepin Isoniazid Butabarbital Naproxen -

Thymol Decreases Apoptosis and Carotid Inflammation Induced by Hypercholesterolemia Through a Discount in Oxidative Stress

http://www.cjmb.org Open Access Original Article Crescent Journal of Medical and Biological Sciences Vol. 4, No. 4, October 2017, 186–193 eISSN 2148-9696 Thymol decreases apoptosis and carotid inflammation induced by hypercholesterolemia through a discount in oxidative stress Roshanak Bayatmakoo1, Nadereh Rashtchizadeh2*, Parichehreh Yaghmaei1, Mehdi Farhoudi3, Pouran Karimi3 Abstract Objective: Atherosclerosis sclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease that can lead to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders that are generally along with hypercholesterolemia and oxidative stress. Various surveys have shown that thymol is a polyphenolic compound with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. This study aimed to investigate the anti- inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects of thymol on carotid tissue of hypercholesterolemic rats. Materials and Methods: Forty male Wistar rats were randomly divided into 4 groups with 10 members each (n = 10): a control group with a normal diet (ND), a group with a high-cholesterol (2%) diet (HD), a group with a high-cholesterol diet combined with thymol (24 mg/kg HD + T), and a group with a thymol diet (T). After preparing serum from peripheral blood of rats, lipid measurements were obtained, including total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides (TG), by using a colorimetric method; the levels of oxidized LDL (OxLDL) were obtained through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) antioxidant enzymes, as well as the concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA) and serum total antioxidant capacity (TAC), were determined with the use of colorimetric methods. The protein expressions of Bcl2 and cleaved caspase 3 and the phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in rat carotid tissue were determined by an immunoblotting method. -

Carbon-I I-D-Threo-Methylphenidate Binding to Dopamine Transporter in Baboon Brain

Carbon-i i-d-threo-Methylphenidate Binding to Dopamine Transporter in Baboon Brain Yu-Shin Ding, Joanna S. Fowler, Nora D. Volkow, Jean Logan, S. John Gatley and Yuichi Sugano Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York; and Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Stony Brook@Stony Brook@NY children (1). MP is also used to treat narcolepsy (2). The The more active d-enantiomer of methyiphenidate (dI-threo psychostimulant properties of MP have been linked to its methyl-2-phenyl-2-(2-piperidyl)acetate, Ritalin)was labeled with binding to a site on the dopamine transporter, resulting in lic (t1,@:20.4 mm) to characterize its binding, examine its spec inhibition of dopamine reuptake and enhanced levels of ificftyfor the dopamine transporter and evaluate it as a radio synaptic dopamine. tracer forthe presynapticdopaminergicneuron. Methods PET We have developed a rapid synthesis of [11C]dl-threo studies were canied out inthe baboon. The pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate ([“C]MP)to examine its pharmacokinet r1c]d-th@O-msth@ha@idate @f'1C]d-thmo-MP)weremeasured ics and pharmacological profile in vivo and to evaluate its and compared with r1cY-th@o-MP and with fts racemate ff@1C]fl-thmo-meth@1phenidate,r1c]MP). Nonradioact,ve meth suitability as a radiotracer for the presynaptic dopaminergic ylphenidate was used to assess the reveralbilityand saturability neuron (3,4). These first PET studies of MP in the baboon of the binding. GBR 12909, 3@3-(4-iodophenyI)tropane-2-car and human brain demonstrated the saturable [1‘C]MP boxylic acid methyl ester (fi-Cfl), tomoxetine and citalopram binding to the dopamine transporter in the baboon brain were used to assess the binding specificity. -

PHD PHARMACOGNOSY- EMMANUEL K. KUMATIA.Pdf

ANALGESIC AND ANTI-INFLAMMATORY CONSTITUENTS OF ANNICKIA POLYCARPA STEM AND ROOT BARKS AND CLAUSENA ANISATA ROOT A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHARMACOGNOSY FACULTY OF PHARMACY AND PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES BY EMMANUEL KOFI KUMATIA KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (KNUST) KUMASI-GHANA AUGUST, 2016 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is the product of my own research work. It does not contain any manuscript that was earlier accepted for the award of any other degree in any University nor any published work of anybody except where cited and due acknowledgments made in the text. ……………………………….. ……………………… Emmanuel Kofi Kumatia Date ………………………………… ……………………… Prof. (Mrs.) Rita Akosua Dickson Date (Supervisor) ……………………………...... ……………………… Prof. Kofi Annan Date (Supervisor) ……………………………...... ……………………… Prof. Abraham Yeboah Mensah Date (Head of Department of Pharmacognosy) ii DEDICATIONS This work is especially dedicated to my mother, Madam Veronica Akoto, my wife, Mrs. Anne Boakyewaa Anokye-Kumatia and my children, Evzen Fifii Kumatia and Eliora Nana Akua Kumatia. iii ABSTRACT Clausena anisata and Annickia polycarpa are medicinal plants used to treat various painful and inflammatory disorders among other ailments in traditional medicine. The aim of this study was to investigate the analgesic/antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of the ethanol extracts of C. anisata root (CRE), A. polycarpa stem (ASE) and root barks (AR) in order to provide scientific justification for their use as anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents. Analgesic activity was evaluated using the hot plate and the acetic acid induced writhing assays. The mechanism of antinociception was evaluated by employing pharmacological antagonism assays at the opioid and cholinergic receptors in the hot plate and the writhing assays. -

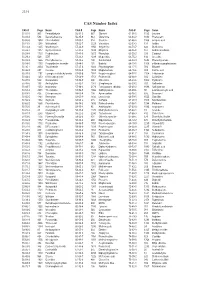

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Essential Oil Flavours and Fragrances

Authenticating Essential Oil Flavours and Fragrances Using Enantiomeric Composition Analysis A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Professor RC Menary and Ms SM Garland University of Tasmania October 1999 RIRDC Publication No 99/125 RIRDC Project No UT-15A i © 1999 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation All rights reserved. ISBN 0 642 57906 7 ISSN 1440-6845 Authenticating Essential Oil Flavours and Fragrances - Using Enantiomeric Composition Analysis Publication no 99/125 Project no.UT-15A The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Prof. Robert C. Menary Ms Sandra M. Garland School of Agricultural Science University of Tasmania GPO Box 252 C Hobart Tas 7001 Phone: (03) 6226 6723 Fax: (03) 6226 7609 RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in October 1999 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint ii Foreword The introduction of international standards to quantify and qualify properties of essential oils has seen the increasing application of analytical technology. -

Pharmacognosy, Phytochemical Study and Antioxidant Activity of Sterculia Rubiginosa Zoll

Pharmacogn J. 2018; 10(3):571-575. A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Original Article www.phcogj.com | www.journalonweb.com/pj | www.phcog.net Pharmacognosy, Phytochemical Study and Antioxidant Activity of Sterculia rubiginosa Zoll. Ex Miq. Leaves Rini Prastiwi1,2*, Berna Elya2, Rani Sauriasari3, Muhammad Hanafi4, Ema Dewanti1 ABSTRACT Introduction: Sterculia rubiginosa Zoll ex.Miq leaves have been used as traditional medicine in Indonesia. There is no report about pharmacognosy and phytochemical study with this plant.Objective: The main aim of this research is to establish pharmacognosy, phytochemical study and antioxidant activity of Sterculia rubiginosa Zoll.ex. Miq. Leaves. The plant used to cure many diseases of Indonesia. Methods: In the present study, pharmacognosy and phyto- 1,2* chemical study of plant material were performed as per the Indonesian Herb Pharmacopoeia. Rini Prastiwi , Berna Results: Microscopy powder of Sterculia rubiginosa Zoll.ex. Miq. Leaves shows star shape Elya2, Rani Sauriasari3, trichoma as a specific fragment. Physicochemical parameters including total ash (17.152 %), Muhammad Hanafi4, acid-insoluble ash (0.922 %), water-soluble extractive (1.610 % w/w), alcohol-soluble extractive Ema Dewanti1 (4.524 % w/w), hexane-soluble extractive (4.005 % w/w), and ethyl acetate-soluble extractive (3.160 % w/w) were evaluated. Phytochemical screening of ethanol extracts showed the 1Department of Pharmacognosy- presence of tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, steroids-terpenoids, glycosides, and phenols. And Phytochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy absent of saponins and Anthraquinones. Antioxidant activity with IC50 157, 4665 ppm and and Science Muhammadiyah Prof.Dr. flavonoid total was 59.436 mg/g quercetin equivalent.