Constructing Activist Identities in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corrective Rape and the War on Homosexuality: Patriarchy, African Culture and Ubuntu

Corrective rape and the war on homosexuality: Patriarchy, African culture and Ubuntu. Mutondi Muofhe Mulaudzi 12053369 LLM (Multidisciplinary Human Rights) Supervisor Prof Karin Van Marle Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Research Problem ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Research questions .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Motivation/Rationale .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Structure .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 2: Homophobic Rape – Stories and response by courts .......................................... 9 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 The definition -

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 8

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 8 South Africa freedomhouse.org In May 2014, South Africa held national elections that were considered free and fair by domestic and international observers. However, there were growing concerns about a decline in prosecutorial independence, labor unrest, and political pressure on an otherwise robust media landscape. South Africa continued to be marked by high-profile corruption scandals, particularly surrounding allegations that had surfaced in 2013 that President Jacob Zuma had personally benefitted from state-funded renovations to his private homestead in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) won in the 2014 elections with a slightly smaller vote share than in 2009. The newly formed Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a populist splinter from the ANC Youth League, emerged as the third-largest party. The subsequent session of the National Assembly was more adversarial than previous iterations, including at least two instances when ANC leaders halted proceedings following EFF-led disruptions. Beginning in January, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) led a five-month strike in the platinum sector, South Africa’s longest and most costly strike. The strike saw some violence and destruction of property, though less than AMCU strikes in 2012 and 2013. The year also saw continued infighting between rival trade unions. The labor unrest exacerbated the flagging of the nation’s economy and the high unemployment rate, which stood at approximately 25 percent nationally and around 36 percent for youth. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 33 / 40 [Key] A. Electoral Process: 12 / 12 Elections for the 400-seat National Assembly (NA), the lower house of the bicameral Parliament, are determined by party-list proportional representation. -

Relocation, Relocation, Marginalisation: Development, and Grassroots Struggles to Transform Politics in Urban South Africa

Photos from: Abahlali baseMjondolo website: www.abahlali.org and Fifa website: Relocation,http://www.fifa.com/worldcup/organisation/ticketing/stadiums/stadium=5018127/ relocation, marginalisation: development, and grassroots struggles to transform politics in urban south africa. 1 Dan Wilcockson. An independent study dissertation, submitted to the university of derby in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of bachelor of science. Single honours in third world development. Course code: L9L3. March 2010 Relocation, relocation, marginalisation: development, and grassroots struggles to transform politics in urban south africa. Abstract 2 Society in post-apartheid South Africa is highly polarised. Although racial apartheid ended in 1994, this paper shows that an economic and spatial apartheid is still in place. The country has been neoliberalised, and this paper concludes that a virtual democracy is in place, where the poor are excluded from decision-making. Urban shack-dwellers are constantly under threat of being evicted (often illegally) and relocated to peri-urban areas, where they become further marginalised. The further away from city centres they live, the less employment and education opportunities are available to them. The African National Congress (ANC) government claims to be moving the shack-dwellers to decent housing with better facilities, although there have been claims that these houses are of poor quality, and that they are in marginal areas where transport is far too expensive for residents to commute to the city for employment. The ANC is promoting ‘World Class Cities’, trying to facilitate economic growth by encouraging investment. They are spending much on the 2010 World Cup, and have been using the language of ‘slum elimination’. -

South Africa February 2013

Blind Alleys PART II Country Findings: South Africa February 2013 The Unseen Struggles of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Urban Refugees in Mexico, Uganda and South Africa Acknowledgements This project was conceived and directed by Neil Grungras and was brought to completion by Cara Hughes and Kevin Lo. Editing, and project management were provided by Steven Heller, Kori Weinberger, Peter Stark, Eunice Lee, Ian Renner, and Max Niedzwiecki. In South Africa, we thank Liesl Theron of Gender DynamiX, Father Russell Pollitt and Dumisani Dube of Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh of Lawyers for Human Rights, and Braam Hanekom and Guillain KoKo of PASSOP (People Against Suffering, Oppression and Poverty) who gave us advice and essential access to its cli- ents. We thank Charmaine Hedding, Sibusiso Kheswa, Siobhan McGuirk, Tara Ngwato Polzer, Sanjula Weerasinghe, and Rachel Levitan for their work coordinating and conducting the field research. Expert feedback and editing was provided by Libby Johnston and Melanie Nathan. We are particularly grateful to Anahid Bazarjani, Nicholas Hersh, Lucie Leblond, Minjae Lee, Darren Miller, John Odle, Odessa Powers, Peter Stark, and Anna von Herrmann. These dedi- cated interns and volunteers conducted significant amounts of desk research and pored over thou- sands of pages of interview transcripts over the course of months, assuring that every word and every comment by interviewees were meticulously taken into account in this report. These pages would be blank but for the refugees who bravely recounted their sagas seeking pro- tection, as well as the dedicated UNHCR, NGO, and government staff who so earnestly shared their experiences and understandings of the refugees we all seek to protect. -

No Valley Without Shadows MSF and the Fight for Affordable Arvs in South Africa

In the 1990s, even as the country celebrated its freedom from apartheid, South Africa descended into a chilling new crisis: an incurable disease was spreading so fast it soon became the fearsome stuff of myth and legend. The fight against HIV/AIDS in South Africa was a war fought on many fronts: against fear and ignorance so powerful it could lead to murder; against profiteering pharmaceutical companies whose patents safeguarded revenues at the cost of patients’ lives; and, most shockingly, against the South African government, which quickly emerged as the world leader in AIDS denialism. To take its place in this battle, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders would have to overcome internal resistance, seemingly impossible financial barriers, multiple lawsuits, and the shame and terror of the very people they were trying to help. How could a coalition of activists, doctors, and patients beat the odds to bring about startling innovations in treatment protocols, end the pharmaceutical companies’ legal challenges to low-cost drugs, and overturn an official policy of denial that originated in the nation’s highest political offices? This is the story. No Valley Without Shadows MSF and the Fight for Affordable ARVs in South Africa Written by Marta Darder, Liz McGregor, Carol Devine and other contributors. © 2014 Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders, Rue Dupré 94, 1090 Brussels No Valley Without Shadows is a publication by Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF). The texts in this publication are based on interviews with members of MSF and others who participated in the fight for affordable ARVs in South Africa. -

It's Torture Not Therapy

It’s Torture Not Therapy A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF CONVERSION THERAPY: PRACTICES, PERPETRATORS, AND THE ROLE OF STATES THEMATIC REPORT 20 irct.org 20 A Global Overview of Conversion Therapy TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Introduction This paper was written by Josina Bothe based on wide-ranging internet 5 Methodology research on the practices of conversion therapy worldwide. 6 Practices The images used belong to a series “Until You Change” produced by Paola 13 Perpetrators Paredes, which reconstructs the abuse of women in Ecuador’s conversion 15 State Involvement clinics, based on real life accounts. Paola, a photographer born in Quito, 19 Conclusions and Recommendations Ecuador, explores through her work issues facing the LGBT community and 20 Bibliography contemporary attitudes toward homo- sexuality in Ecuador. See: https://www.paolaparedes.com/ 2020 © International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Cover Photograph In front of the mirror, the ‘patient’ is observed by The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) another girl, who monitors the correct application is an independent, international health-based human rights organisation of the make-up. At 7.30am, she blots her lips with which promotes and supports the rehabilitation of torture victims, pro- femininity, daubs cheeks, until she is deemed a motes access to justice and works for the prevention of torture world- ‘proper woman’. wide. The vision of the IRCT is a world without torture. From “Until You Change” series by -

South Africa 2

The Atlantic Philanthropies South Africa 2 Honjiswa Raba enjoysThe the new auditorium of the Isivivana Centre.Atlantic Raba is head of human resources Philanthropies for Equal Education, a Centre tenant, and is a trustee of the Khayelitsha Youth & Community Centre Trust, the governing body of Isivivana. Foreword 5 Preface 9 Summary 13 South Africa 22 Grantee Profiles 89 Black Sash and Community Advice Offices 91 Legal Resources Centre 96 University of the Western Cape 101 Lawyers for Human Rights 108 Umthombo Youth Development Foundation 113 Archives and the Importance of Memory 117 Nursing Schools and Programmes 125 Health Care Systems 131 LGBTI Rights 135 Social Justice Coalition 138 Equal Education 143 Isivivana Centre 147 Lessons 154 Acknowledgements 175 Throughout this book, the term “black” is used as it is defined in the South African Constitution. This means that it includes Africans, coloureds and Indians, the apartheid-era definitions of South Africa’s major race groups. The Atlantic Philanthropies South Africa BY RYLAND FISHER President Cyril Ramaphosa met with Chuck Feeney in Johannesburg in 2005 when they discussed their involvement in the Northern Ireland peace process. Ramphosa was elected president of South Africa by Parliament in February 2018. DEDICATION Charles Francis Feeney, whose generosity and vision have improved the lives of millions in South Africa and across the globe IN MEMORIAM Gerald V Kraak (1956–2014), a champion of human rights and Atlantic’s longest serving staff member in South Africa Students “No matter how some of the visit the Constitutional Court at ideals have been difficult Constitution Hill. to achieve and get a bit frayed around the edges, South Africans still achieved its transition to democracy in, I think, one of the most extraordinary ways in human history.” Christine Downton, former Atlantic Board member 5 South Africa Foreword he Atlantic Philanthropies are known for making big bets, and it’s fair to say that the foundation was making a very large wager when T it began investing in South Africa in the early 1990s. -

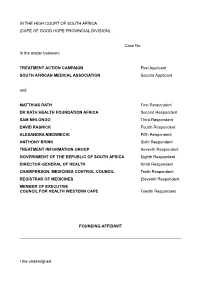

I, the Undersigned

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA (CAPE OF GOOD HOPE PROVINCIAL DIVISION) Case No. In the matter between: TREATMENT ACTION CAMPAIGN First Applicant SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION Second Applicant and MATTHIAS RATH First Respondent DR RATH HEALTH FOUNDATION AFRICA Second Respondent SAM MHLONGO Third Respondent DAVID RASNICK Fourth Respondent ALEXANDRA NIEDWIECKI Fifth Respondent ANTHONY BRINK Sixth Respondent TREATMENT INFORMATION GROUP Seventh Respondent GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Eighth Respondent DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF HEALTH Ninth Respondent CHAIRPERSON, MEDICINES CONTROL COUNCIL Tenth Respondent REGISTRAR OF MEDICINES Eleventh Respondent MEMBER OF EXECUTIVE COUNCIL FOR HEALTH WESTERN CAPE Twelfth Respondent FOUNDING AFFIDAVIT I the undersigned 2 NATHAN GEFFEN hereby affirm and state as follows: 1. I am an adult male. I am employed by the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) at 34 Main Road Muizenberg. 2. My position at the TAC is Co-ordinator of Policy, Research and Communications. I hold an M.Sc. in computer science from the University of Cape Town (UCT). 3. During 2000 and 2001 I was a lecturer in computer science at UCT. In this period I also volunteered for the TAC. This included serving as the organisation’s treasurer. From 2002 to the beginning of 2005 I was employed by the TAC as its national manager. 4. I am duly authorized by a resolution of the TAC National Executive Committee (NEC) to make this application and depose to this affidavit on its behalf. A copy of the resolution of the NEC on 4 October 2005 is attached (NG1). 5. The facts contained herein are true and correct and are within my personal knowledge unless the context indicates otherwise. -

Report Was Written by Scott Long, Consultant to Human Rights Watch and Former Program Director of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission

MORE THAN A NAME State-Sponsored Homophobia and Its Consequences in Southern Africa I wanted to speak to my president face to face one day and tell him, I am here. I wanted to say to him: I am not a word, I am not those things you call me. I wanted to say to him: I am more than a name. ⎯Francis Yabe Chisambisha, Zambian activist, interviewed in 2001. Human Rights Watch and The International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission Copyright © 2003 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-286-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2003102060 Cover photograph: Cover design by Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, DC 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (44 20) 7713 1995, Fax: (44 20) 7713 1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (32 2) 732-2009, Fax: (32 2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to hrw-news-subscribe @igc.topica.com with “subscribe hrw-news” in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Addresses for IGLHRC 1375 Sutter Street, Suite 222, San Francisco, CA 94109 Tel: (415) 561-0633, Fax: (415) 561-0619, E-mail: [email protected] IGLHRC, c/o HRW 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 216-1814, Fax: (212) 216-1876, E-mail: [email protected] Roma 1 Mezzanine, (entrada por Versalles 63) Col. -

Ungovernability and Material Life in Urban South Africa

“WHERE THERE IS FIRE, THERE IS POLITICS”: Ungovernability and Material Life in Urban South Africa KERRY RYAN CHANCE Harvard University Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches . we shall liberate this country. —Winnie Mandela, 1986 Faku and I stood surrounded by billowing smoke. In the shack settlement of Slovo Road,1 on the outskirts of the South African port city of Durban, flames flickered between piles of debris, which the day before had been wood-plank and plastic tarpaulin walls. The conflagration began early in the morning. Within hours, before the arrival of fire trucks or ambulances, the two thousand house- holds that comprised the settlement as we knew it had burnt to the ground. On a hillcrest in Slovo, Abahlali baseMjondolo (an isiZulu phrase meaning “residents of the shacks”) was gathered in a mass meeting. Slovo was a founding settlement of Abahlali, a leading poor people’s movement that emerged from a burning road blockade during protests in 2005. In part, the meeting was to mourn. Five people had been found dead that day in the remains, including Faku’s neighbor. “Where there is fire, there is politics,” Faku said to me. This fire, like others before, had been covered by the local press and radio, some journalists having been notified by Abahlali via text message and online press release. The Red Cross soon set up a makeshift soup kitchen, and the city government provided emergency shelter in the form of a large, brightly striped communal tent. Residents, meanwhile, CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 30, Issue 3, pp. 394–423, ISSN 0886-7356, online ISSN 1548-1360. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY “2010 FIFA World Cup FNB TV Commercial.” Online video. 8 Feb. 2007. YouTube. 4 July 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjPazSFQrwA. “60’s Coke Commercial.” Online video. 13 Jan 2011. YouTube. 3 July 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQWoztEPbP4. A Normal Daughter: The Life and Times of Kewpie of District Six . Dir. Jack Lewis. 2000. “Abahlali Youth League Secretariat.” Abahlali baseMjondolo . Web. 1 Feb. 2012. http://abahlali.org/node/3710. “AbM Women’s League Launch—9 August 2008.” Abahlali baseMjondolo . Web. 1 Feb. 2012. http://abahlali.org/node/3893. Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 79, 22.1 (2004): 117-139. Web. 23 March 2011. ---. The Cultural Politics of Emotions . Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2004. Print. Alphen, Ernst van. “Affective operations in art and literature.” Res 53/54 (2008): 20-30. Web. Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Refl ections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism . London / New York: Verso, 2006. Print. Appadurai, Arjun. Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger . Durham / London: Duke UP, 2006. Print. Attridge, Derek. J.M. Coetzee and the Ethics of Reading . Chicago / London: U of Chicago P, 2004. Print. Attwel, David. “‘Dialogue’ and ‘Fulfi llment’ in J.M. Coetzee’s Age of Iron .” Writing South Africa. Literature, Apartheid, and Democracy, 1970-1995 . Eds. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 221 H. Stuit, Ubuntu Strategies, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-58009-2 222 BIBLIOGRAPHY Derek Attridge and Rosemary Jolly. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998: 166- 179. Print. Baderoon, Gabeda. “On Looking and Not Looking.” Mail & Guardian . -

Abahlali Basemjondolo Movement SA Presentation to the Standing Committee on Appropriations (The Committee) Established in Terms

Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement SA P.O Box 26 Phone: (031)304 6420 Umgeni Park Fax: : ( 031) 304 6436 4098 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http//www.abahlali.org. ......................................................................................................................................................... Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement SA Presentation to the Standing Committee on Appropriations (the Committee) established in Terms of the Money Bills Amendment Procedure and Related Matters Act No. 9 of 2009 (the Act). By: Mr. Thembani Jerome Ngongoma the National Spokesperson of Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement Movement SA. Addressed to the Chairperson of the Standing Committee on Appropriation SUBJECT: The 2018 Budget Dialogue TBC Wednesday 16TH May 2018 Thank you Chairperson of the Standing Committee of on Appropriation, greetings to all in the house and please allow me to say all protocols observed. I am very pleased as a person to have been trusted and sent by my own organization to represent it in such a remarkable event, at least for a moment I feel a sense of ownership and belonging to the processes that are meant to better the lives of ordinary South African citizens. We must also thank the organizers who had our organization in mind as a valued stakeholder. As one of those citizens who does have a reason to doubt his citizenship, that which also applies to my comrades and or colleagues, I confidently stand before you now, not to convey my own individual feelings in this dialogue but to try by all means to put on the table the true reflection of what is happening at the grassroots level. We are here to assist this Standing Committee to see things through an eye of an ordinary man in the street, because that is exactly who and what we are, the Ordinary South Africans that expect to be respected and listened to.